Cigarettes and the White Slave Trade

In the USA, the acceptance of cigarette smoking was concomitant to Austro-Hungarian slaving networks infiltrating first domestic organized crime (beginning 1850s), then opinion-forming industries like the theater and ultimately the movies. The critical point for this media-infiltration came with WWI, when the Roosevelt family and British interests used our military as a springboard for a pro-smoking ‘public service’ campaign. A scion of one of Monroe, WI’s most prominent families, William Wesley Young, played an outsized role in this pro-smoking campaign.

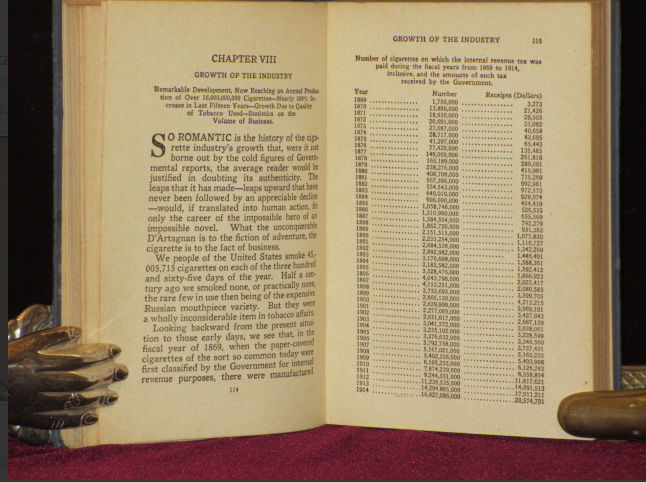

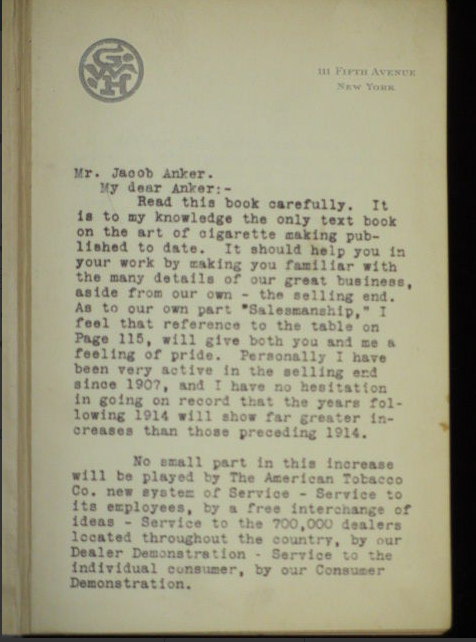

[The images above show W.W. Young’s 1916 book, The Story of the Cigarette, which he was hired by ‘American Tobacco Company’ executive George Washington Hill to write. Hill is the signatory of the promotional letter that went out with this particular copy. A few years later, Hill would engage advertising guru (and Sigmund Freud’s in-law) Edward Bernays to convince American women to take up the unhealthy habit.]

WWI also catalyzed the partnership between film pornographers and the US Navy under Josephus Daniels, which birthed Hollywood. The White Slave Trade is the common denominator between the history of cigarette smoking and the US film industry.

As someone who grew up in the 1990s, to hear that cigarettes were decried as “coffin nails” in the 1890s seemed bizarre: my historical miseducation lead me to believe that cigarette-smoking, like pipe-smoking or chew, was a longstanding tradition from our nation’s bad old days. For some groups of people cigarette-smoking was a traditional habit, but not for my ancestors and likely not the ancestors of the majority of people reading this post. Until WWI, cigarette smoking was seen as a criminal-habit amongst smugglers, pirates and prostitutes from the port cities of Southern and Eastern Europe (largely Hapsburg ports). While pipes and chew were socially acceptable in the pre-1850s USA, the more habit-forming cigarette-smoking— yes the old-timers understood this— was strongly looked down upon.

Smoking-Prostitution-Vaudeville: This detail comes from a larger image on a 1906 USA-made “Vienna Art Plate”— a tin plate— advertising Duff Gordon Sherry. At this time in the USA, smoking was associated with prostitution, as were ladies of the stage. This same plate also celebrated the famous prostitute/dancer ‘“La Belle Otero” of the Folies Bèrgere, which inspired Ziegfeld’s NYC girlie show. Duff Gordon sherry imports provided the seed money for Ziegfeld-costumer Lucy Duff Gordon’s lingerie empire. Check out that link above: more piracy connections, readers.

In the USA, cigarette smoking was particularly associated with ‘Jewish prostitutes’, that is the immigrant women trafficked for the sex trade by Jewish pimping networks based out of Hapsburg lands. These lands included Hungary, Galicia [Poland] and those Balkan territories recently acquired by Emperor Franz Joseph’s Foreign Office junta. (Before WWI, one quarter of US cigarettes were sold in NYC, where the Hungarian branch of this network first put down American roots in the 1850s. See Bristow, Prostitution and Prejudice.) Tellingly, American euphemisms for cigarettes included the appellation “little white slavers” and most of the information from this post comes from Cassandra Tate’s book Cigarette Wars: The Triumph of “The Little White Slaver”.

How did the practice of chopping up tobacco and burning it in a paper straw make it to those Mediterranean ports which the Hapsburgs groomed to be their answer to British imperial trading networks? (See Dubin, The Port Jews of Hapsburg Trieste.) In the same way the British built their Atlantic trade: partnering with criminal elements from Spain’s and Portugal’s South American possessions. A goodly portion of this South American criminal element were Jewish agents of Iberian empires, whose ancestors had originally fled to (invested in) the New World when popular politics in Spain and Portugal turned against them post-1492. These agents had the navigation skills and diaspora contacts to fence illegal goods en masse. Contraband trade in precious metals, medicines and people was the vector that brought cigarette smoking in particular to Hapsburg Europe.

By the mid-1800s, the Hapsburgs and their camerialist cronies had long sought to replicate Western European global trading networks, particularly that of the British. Even as their European empire crumbled, this ancient family sought more difficult-to-govern Central American possessions.

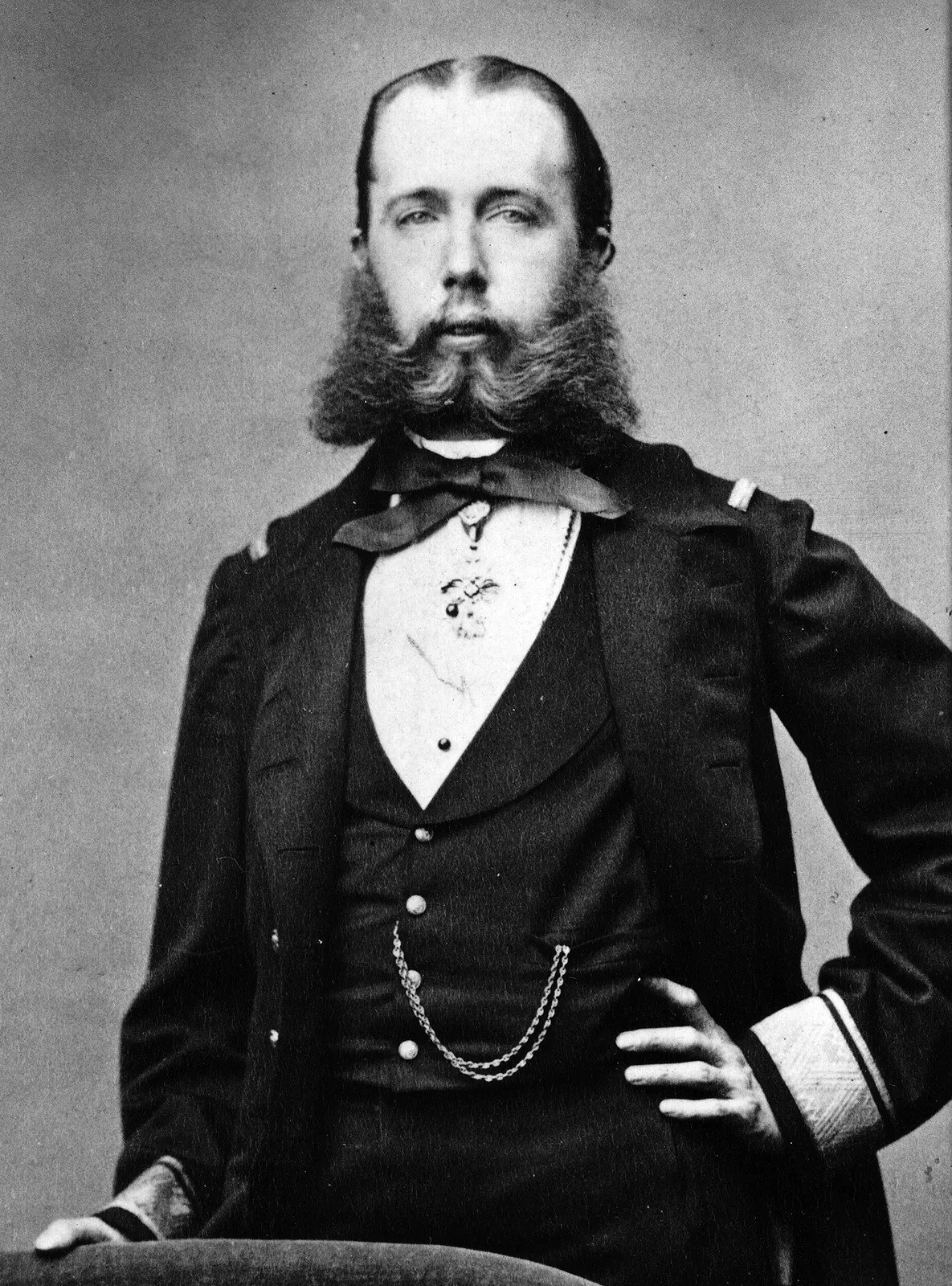

Encyclopedia Britanica:”Maximilian, in full Ferdinand Maximilian Joseph, (born July 6, 1832, Vienna, Austria—died June 19, 1867, near Querétaro, Mex.), archduke of Austria and the emperor of Mexico, a man whose naive liberalism proved unequal to the international intrigues that had put him on the throne and to the brutal struggles within Mexico that led to his execution.”

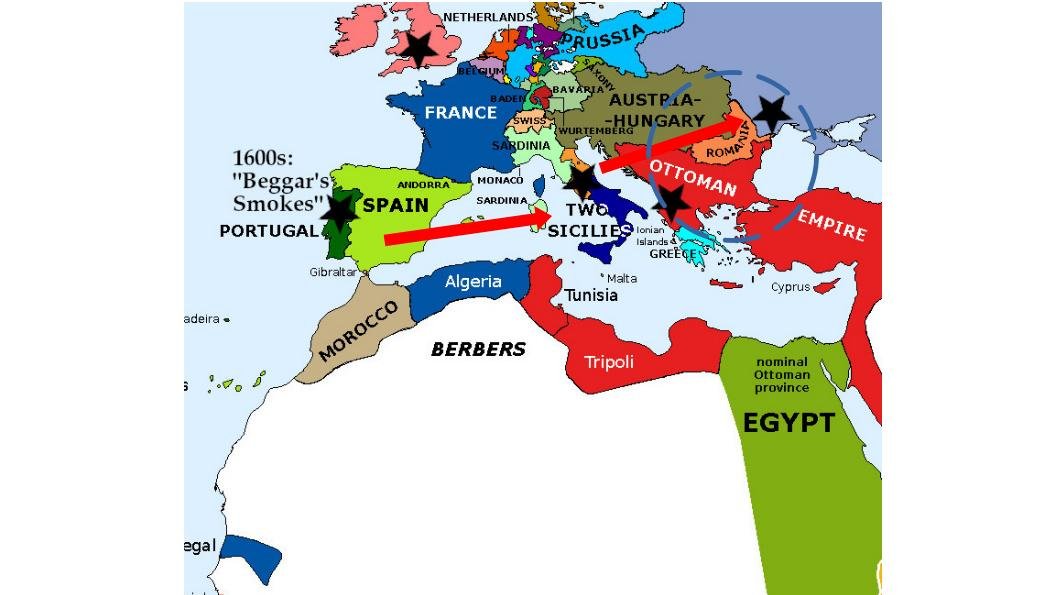

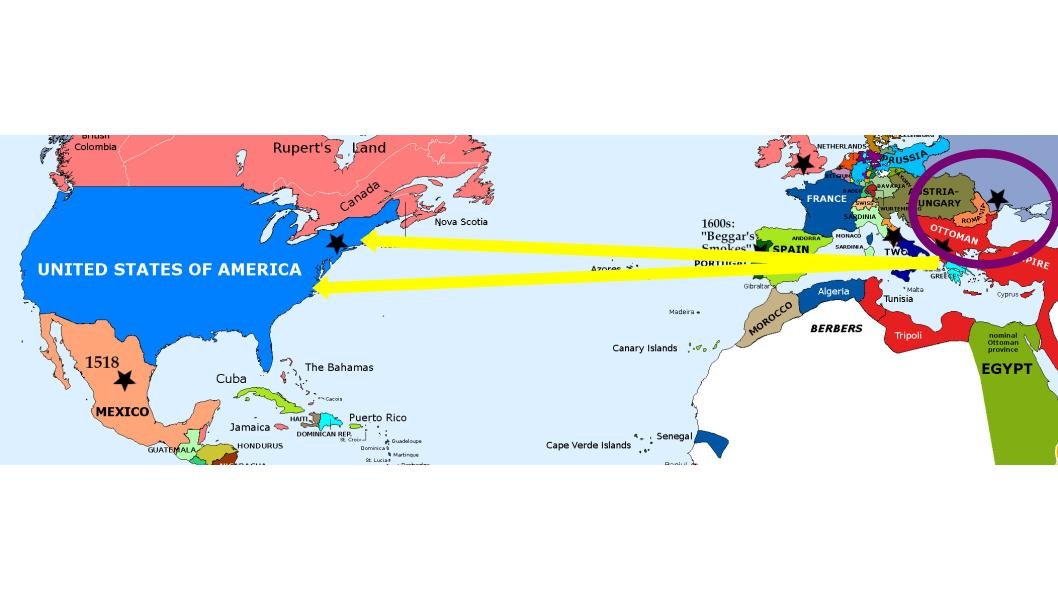

I wanted to give readers a clear map of Mediterranean trade routes with South America, but this topic is understudied and I couldn’t find one! Instead, I’m providing the two maps below. Firstly, readers may see how comfortably, from a seasonal perspective, Hapsburg ports fit into the rhythm of New World trade. In some respects Hapsburg naval domination would have made more sense than what happened historically: British (prior to 1890s) then Prussian naval domination. Good weather is particularly important for shipowners when functioning insurance markets are not present, i.e. for shipowners engaged in piracy and/or shipping sponsored by less-developed states. During the period in question (1830s-1918) the Hapsburgs tried to develop ‘Austrian Lloyds’ to compete with the original London-based Lloyds, the world’s biggest and best functioning naval insurance market. (‘Lloyds’ was not a catch-all 19th century German name for a naval insurance operation (!), but a name used for a very specific type of imperialist-minded, private-public insurance partnership designed to bolster naval power. Continental ‘Lloydses’ were challenges to British hegemony of the seas.)

Austrian Lloyds’ palatial headquarters in Trieste. Along with Czernowitz in modern Poland, Trieste was one of the two main exit points for Austria-Hungary sourced slaves. AL was at the center of Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s attempt to curb male human trafficking and bolster military enlistment numbers. (See Kronenbitter, Krieg am Frieden.)

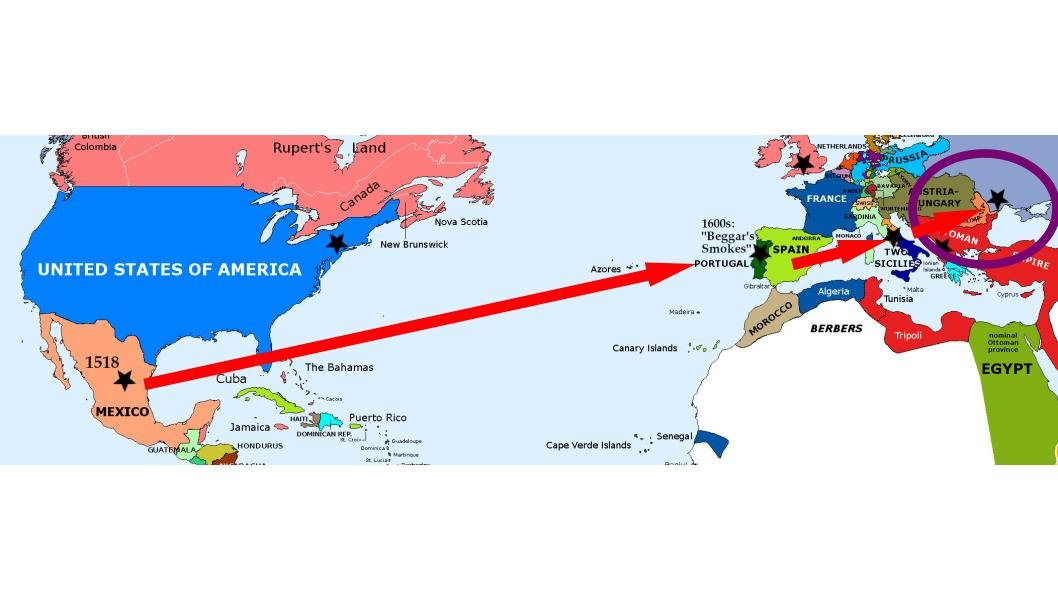

The map below shows how cigarette smoking spread from Mexico (first recorded 1518), to Portugal and Spain, and then Southern Russia (throughout the 1600s). This export from Mexico is represented by red arrows below. During this migration, cigarettes were very much a low-class phenomenon. In Russia they made the transition to the upper classes (around the time of Peter the Great’s ‘enlightening’ reign), from where they became widespread among the rich of Southern and Eastern Europe. This time period of eastward migration overlaps with the beginning of the “enlightenment”/Protestant era in Central Europe, an era notable for its Muslim influence and uptick in White slave trafficking into the Ottoman/African world. This slaving was largely carried out by marginal groups such as Armenians, Jews and Greeks . I discuss this in Islam and the Monroe Twinings.

The purple circle on the map represents the area in which lower-class habits became higher-class ones, to the tune of Ottoman/European “cultural transfer”. Modern military-psychological ideas and “Renaissance Hermeticism” were other novelties which slave-merchants brought back to Europe via concomitant trade.

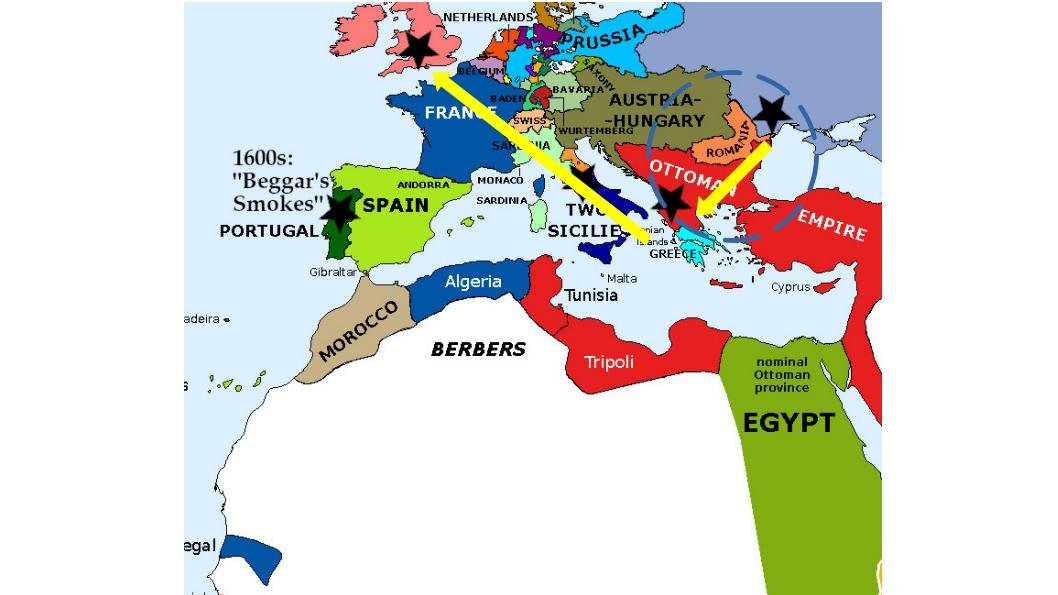

Cigarettes began to make their way westward again after the social dislocations of 1848 and the rise of both anglophone and Hapsburg military opportunities for Eastern Europeans. (Smoking cigs is now a military/”moneyed” habit, yellow arrows.) British soldiers began smoking during the Crimean War (1853-56), while post-1848 immigration brought cigarette smoking to NYC (mostly among women aping socially-aspirant foreigners in the 1850s) and among Yankee officers in post-US Civil War Virginia. I’m going to talk about those NYC women below, but to understand the Civil War connection, consider the Ziegfeld family’s role during the Reconstruction and General Grant’s war-time provisioning experiences. Smuggling and espionage.

The fashion for cigarettes in the Balkans was at least in part enabled by their acceptance among richer people in Russian-speaking lands. From Crimea (the eastern edge of the purple circle) British soldiers brought the habit home.

It was from Eastern Europe, rather than England, that cigarettes found their way back to North America. Eastern European human-traffickers made sure plenty of labor was smuggled out of for example Galicia, or newly-acquired Balkan lands, to work in, for example, Empire City cigarette factories. This provided employers like James Buchanan Duke with a cheap, less-mobile workforce and provided those same trafficking gangs with a vector through which to infiltrate American cities. (Duke could move these people— almost entirely Eastern European Jews— wherever he chose, according to Tate.)

Post-1848 cigarette migrations to the USA from Eastern Europe.

Who was this James Buchanan Duke? His backstory marries all aspects of the cigarette phenomenon. Duke was the son of a New England carpetbagger, who grabbed a chunk of the Southern tobacco industry after the Civil War. Duke exploited his Northern contacts, and the corruption which set in during the Reconstruction, to create both the US tobacco monopoly (1890-1911) as well as the native US cigarette market. He didn’t do this through business savvy or offering a superior product, he did it through manipulating tobacco legislation.

James Buchanan Duke and his daughter Doris. This unfortunate family suffered from the type of dysfunction you’d expect to find in an NYC tenement house. Image from Duke Farms.

Duke was able to build his business because he stayed ahead of tobacco legislation, both out of D.C. and from state legislators. Between 1880-1911, Duke had a network of dedicated lobbyists, used economic violence, and bald-faced corruption to reach his political goals. His political influence was based largely on patronage from the Mark Hanna Junta, who Goetz fans know from Leon’s curious submarine patent in 1910. The Hanna Junta had very reluctantly made Teddy Roosevelt’s first elected term as president, so naturally their star faded over the course of this radical politician’s career. From Dictionary of North Carolina Biography:

An "Old Guard Republican" and great admirer of President William McKinley and Senator Mark Hanna, Duke had good reason to fear President Theodore Roosevelt and his "trust busting." The federal government's antitrust action against the American Tobacco Company was launched in 1907 and culminated in 1911 when the Supreme Court ordered the dissolution of the giant combination. Except for the British-American Tobacco Company, which was headquartered in London, Duke dissociated himself from the tobacco industry after 1911.

Hanna’s cozy and criminal relationship with Britain via Great Lakes arms-dealing perhaps explains American Tobacco’s cozy relationship with British Tobacco interests in the face of Roosevelt political prosecution. Roosevelt and Duke didn’t stay on bad terms for long, though. It was William Wesley Young’s boss from 1908, Benjamin B. Hampton, an American Tobacco Company executive, who brokered a peace between Roosevelt and Duke and saved Duke from becoming a casualty like Thomas Edison would become later. Read all about that here. (The timing of W. W. Young’s career with Hampton suggests Duke branched out into the theater/movie world in anticipation of Teddy Roosevelt’s removing favor from his tobacco monopoly.)

I get ahead of myself: let’s step back to Duke’s early days with the American Tobacco Company.

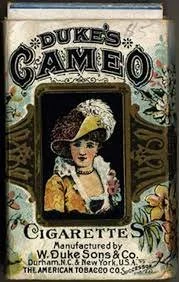

An early Duke cigarette pack.

James Buchanan Duke was infamous for his womanizing, but even more so for his bald-faced corruption. Tate: “Duke’s willingness to slide on the shady side of the law suggests something about the marginal position of cigarettes in American commerce.” He employed a fleet of lawyers and fixers to openly bribe lawmakers— one of these fixers being our local boy William Wesley Young’s boss Benjamin B. Hampton. (At the end of his career Hampton wrote a book gently exposing Hollywood’s sex-trade roots.)

Duke’s corruption-strategy was not always successful. One example from 1904: leading up to a vote on whether to legalize cigarette sales, Rep. Ananias Baker threw down an envelope of Duke money on the Indiana legislature’s floor— US$100 spilled out. Rep Baker explained how he’d been sent this to vote in Duke’s favor, and thereby ensured the failure of Duke’s cause by questioning the honor of anyone who voted for it.

Bribing law-makers to lower taxes or not ban cigarettes was only one half of Duke’s strategy. He had to create a market for these “coffin nails” and fight the wide-spread social consciousness of cigarettes’ unhealthiness and criminal associations.

When Duke got into business in 1881, most cigarettes were made by immigrant workforces in NYC, sold to immigrant workforces, and cigarettes accounted for a very small share of the national tobacco market.

As a consequence to these economic realities, cigarette smoking was associated with immigrant labor in the USA. Cigarette-smokers typically fell into two groups: 1) urban, Jewish day-laborers and prostitutes who consumed cheaper, mild, American-grown tobaccos, as well as 2) the type of industrialists who would employ both these laborers and prostitutes. (These industrialists consumed expensive, strong Turkish tobacco). Cigarette smoking was viewed as a “dandy’s” habit, and this perception was entrenched by men like Oscar Wilde’s love of cigarette smoking. Masculine men, nice women and anyone concerned with their own health, or the health of their workforce, didn’t smoke these things.

“A cigarette is the perfect type of a perfect pleasure. It is exquisite, and it leaves one unsatisfied. What more can one want?” This quote shows Wilde stumping for a very specific portion of the tobacco industry via The Portrait of Dorian Gray. Wilde was a favorite among the liberal “Ringstrasse” set who patronized Sigmund Freud and profited from the Galician-Jewish dominated White Slave Trade.

What Duke was doing with his championship of the cigarette was the same ‘mainstreaming’ of bordello-culture that Lucy Duff Gordon and her sister championed through their “It-girl” fashion empire and Ziegfeld partnership.

It was widely understood in the 19th century that diseases like lung cancer, heart disease and emphysema were linked to cigarette smoking in particular. They also knew cigarettes were curiously addictive— more addictive than other types of tobacco use— and that addicted people weren’t very efficient workers. Tate:

Far more significant than doctors in the early anti-smoking movement were businessmen, many of whom regarded cigarettes as impediments to efficiency. Cigarette smokers seemed either nervous or stupefied, [neurotic?] in either case lacking the steadiness needed for modern industry and business…

Elbert Hubbard, the so-called “Sage of East Aurora” (New York)— a former soap salesman who helped revive the Arts and Crafts movement in America by preaching positive thinking, perseverance, and enterprise to entrepreneurs— said cigarette smokers simply could not be trusted. Hands that hold cigarettes, he said, “are the hands that forge your name and close over other people’s money.” Dozens of major employers agreed with him…

Among these employers were both Protestants and (German) Jews: Montgomery Ward’s William C. Thorne, Andrew Carnegie, Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, Sears and Roebuck’s Julius Rosenwald and department store owner John Wanamaker as well as many of the owners of regional railway lines. Since the Galician Network expanded by opening whore-houses and smuggling along railway lines, that Jewish immigrant workers were discouraged from working certain geographies because of anti-smoking policies acted as a barrier to entry into new criminal markets. Duke was particularly focused on breaking down anti-smoking sentiment among railway owners.

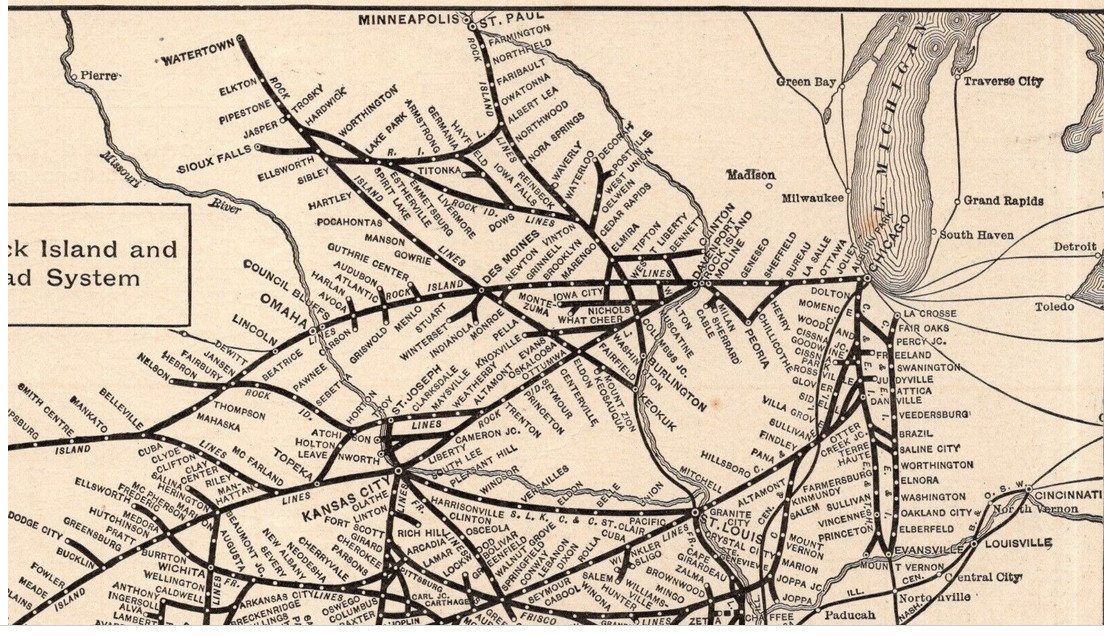

When open bribery didn’t work, Duke resorted to financial hardball. His influence among business owners suggests powerful allies in finance. Here’s an example of his financial clout: Duke’s surviving correspondence shows that he concentrated on opening up the railway through Rock Island, IL to immigrant labor/cigarette smokers in particular. Ten years after Duke’s meddling, this railway would be the stomping ground for John Patrick Looney’s vice empire. (I wrote about Looney, the Goldman Family, and A. D. Harris’s Rock Island narcotic network with regard to Monroe theater owner Leon Goetz and his Mann Act (slaving for the sex-trade) indictment. This network appears to have sold German-manufactured morphine after WWI, among other drugs too.) Tate:

Elsewhere, however, Duke sought to defend cigarettes on a broader basis. In an uncharacteristically long letter to W. C. Purdy, president of the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railway, he insisted that “cigarette smoking is no more injurious than smoking in any other form.” Purdy had announced that any employees who smoked cigarettes, on or off duty, would be fired: he apparently believed that such people were unproductive and inattentive. Duke grumbled that the policy was “entirely unjust”…He insisted that any discrimination against cigarettes was at odds with American notions about fair play and tolerance.

Duke was obviously concerned that anti-cigarette policies adopted by large employers could undermine his business. He could discount, at least publicly, attacks made by what he called “irresponsible agitators, or professional so-called reformers.” [i.e. WCTU] Those that came from railroad presidents and other prominent businessmen were harder to ignore. He sent Purdy a copy of “The Truth About Cigarettes”, a 48-page booklet absolving cigarettes of any ill effects; asked him to read it; and offered to arrange a meeting in the hope of “a modification of the order which you have made.” In case Purdy needed additional persuasion, Duke also pointed out that some of the same people who had invested in the Chicago, Rock Island, and Pacific Railway had also invested in American Tobacco [Duke’s monopoly], and “[t]hese investments would be made less profitable, and less secure, with the diminution of the cigarette business.” Duke thus deftly combined an appeal to democratic principles with a veiled threat of economic retaliation.

Why was Duke so eager to change Purdy’s mind about cigarette smokers? The rail line in question covered a huge part of the USA. Purdy’s policies made life difficult for Duke and the snakeheads who supplied him with workers.

A close-up of the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific line (1914) as it relates to Goetz interests. Note how the map encompasses the Shallenberger Brothers’ territory (Waterloo-Chicago) as well as the Goldman/Looney territory of Davenport-Kansas City. Leon Goetz’s porn partners worked the Kansas City-Chicago-St Louis-Detroit area.

James Duke’s relationship with the human traffickers who supplied much of his workforce, especially in the early years, deserves special scrutiny because of the nature of the White Slave Trade. During the Civil War years, prostitution exploded in the USA and this growth was by enlarge not due to wartime deprivation, but rather entertaining/distracting severely dispirited and embittered soldiers. (See Public Women and the Confederacy, by Catherine Clinton). Sourcing “women” for bordellos was and is largely a matter of grooming children for sex work. After grooming— acculturation into the trade by young pimps, typically—- these children would then be sold into the vast international bordello system, ultimately organized out of Austria-Hungary. A ten-year old brought into sex work was more valuable than a 25 year-old, partly because the pedophile market was very lucrative, and partly because 35-10 is a higher number than 35-25. That the sex trade always targets children is simple economics.

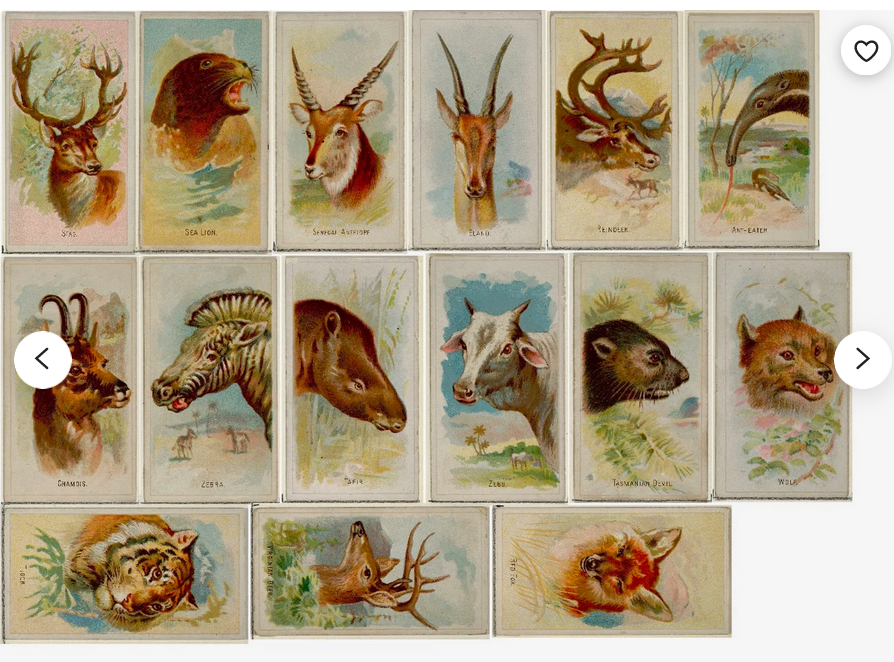

What role did the cigarette industry play in this grooming process? The same role supplying alcohol to minors plays in grooming today. Back then cigarettes were marketed to children in particular.

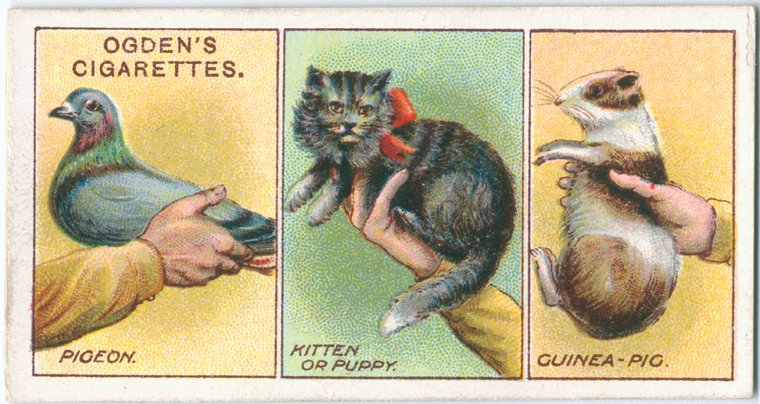

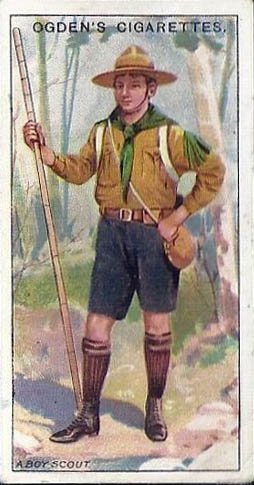

Cigarette packages came with colorful “trade cards”— not unlike the Pokemon cards sold to kids now— and featured images of famous actors, animals, pretty ladies… exactly the sort of thing to appeal to children. The selection above comes from the 1880s-1910s. The book cover is from John Broom’s “History of Cigarette & Trade Cards: The Magic Inside the Packet”.

Legislation against cigarettes in the USA was overwhelmingly designed to protect children from cigarettes. While only about half of the states outlawed cigarette sales altogether, all states outlawed cigarette sales to children save Rhode Island and Virginia. Lawmakers and activists understood that cigarettes were marketed to children and were a tool of child grooming.

This is a very important point, because law enforcement knew that organized prostitution sourced the majority of its victims through child-grooming. Where law enforcement succeeded in combating the White Slave Trade, they focused their efforts on protecting vulnerable children rather than reforming adult prostitutes. (See Police Women of Poland, Paleolog). Under-supervised children would have seen pimps on the street, famously over-dressed and dripping with gold, smoking their unusual ‘cigarette’ things and making fabulous promises of wealth. Children in factories would have seen well-dressed women smoking these things out of windows in stone buildings on their walk home from poorly-paid work. Cigarettes were famously cheap too: pimps could easily afford to love-bomb with these exotic-seeming treats.

Cigarette advertising would be some of these children’s first exposure to sex. Cigarettes, cheap for pimps to hand out and even cheap enough for children to afford, often came with pornographic images inside the packaging. Showing children porn is now widely recognized as one stage in the grooming process with an eye towards eventual sexual exploitation. That cigarette smoking should predominate among a demographic which specialized in this grooming rightly raised red flags for socially-conscious people. Tate:

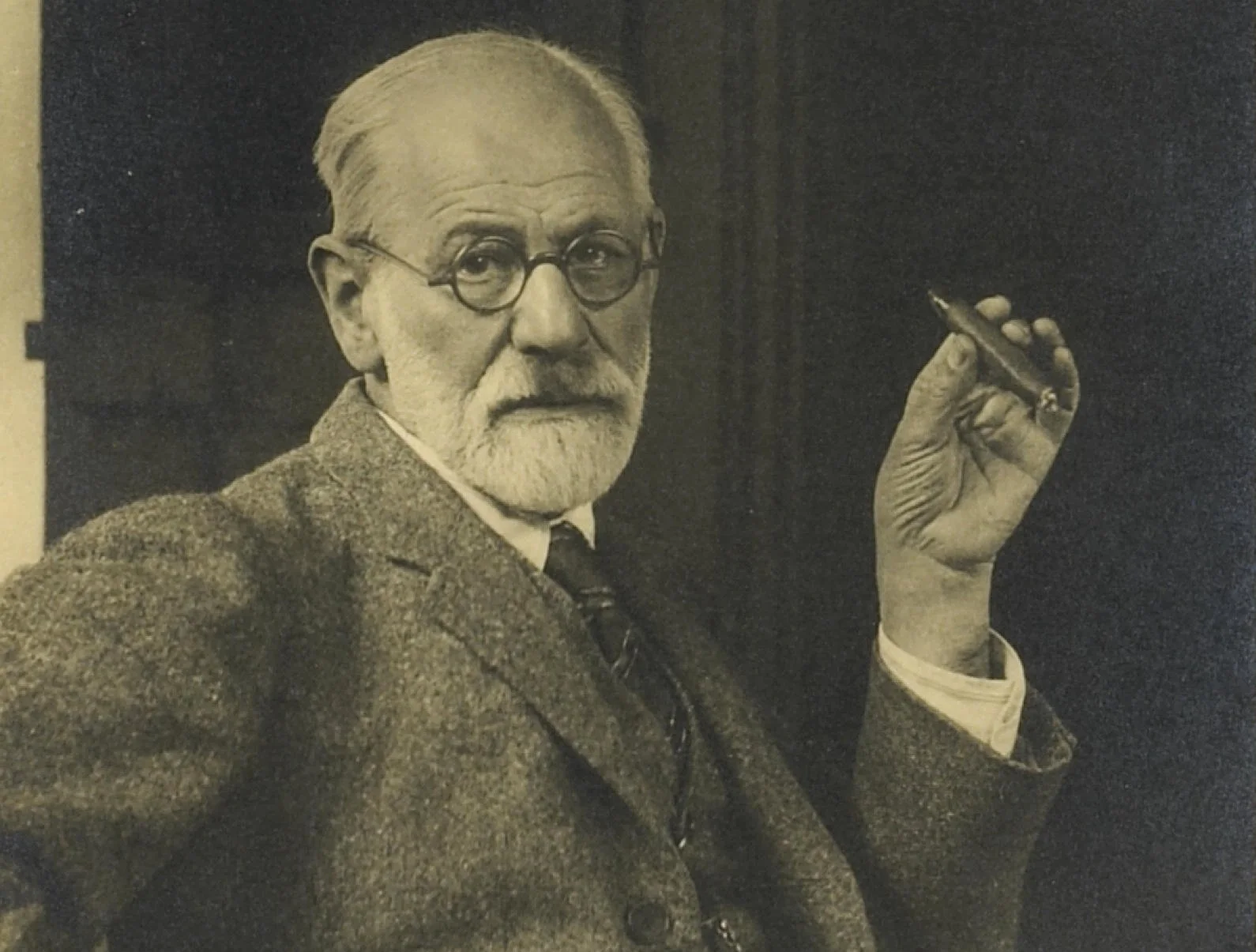

One writer [anti-cigarette activist] warned darkly that cigarette smoking, especially by women, would lead to “degredation [sic] altogether beyond what comes of being a slave to the vile weed.” A somewhat less circumspect writer claimed that cigarettes were “an ally of the white slave traffic” because they would be easily drugged and thus employed in the ruination of young girls. According to another, “The boy who smokes at seven, will drink whiskey at fourteen, take to morphine at 20 or 25, and wind up with cocaine and the rest of the narcotics, at 30 and later on.” [Quite Sigmund Freud’s personal experience!] Like today’s anti-smoking activists— who depict the cigarette as a “gateway” drug, leading to alcohol, marijuana, and harder drugs— earlier reformers saw connections between cigarettes and other social problems.

White slave imagery was a staple for cigarette advertisers. For more on this topic, please see my post on Cosmo’s Spooky Aunt: Lucie Duff Gordon.

Of course, these street gangs groomed with an eye to meeting their girl-quota and recruiting new low-level gang members. But this wasn’t their only interest in children. I’ll remind readers here that many 19th century bordellos made a special point of trying to attract urban boys as customers: the Flexner report of 1914 noted how Viennese secondary school (“Gymnasium”) teen boys were disproportionately patrons of prostitutes. The “Gymnasium” element is important here, because it denotes 1) boys with some money to spend and 2) a highly disproportionate number of Jewish boys from the same backgrounds as the pimps and 3) the new “Dienstadel” class of imperially-favored pseudo-aristocrats. This situation was replicated in other European cities, but the economic logic stayed the same. The pimps’ socioeconomic targeting was done in order to habituate these boys to satisfy themselves with prostitutes, i.e. ‘hook em while their young’.

This attack by sex-merchants was two-pronged: while exploiting the emotional immaturity of punters, merchants would also artificially stimulate desire for sex by providing pornographic art, films, stage shows etc. to boys at every opportunity. (See Flexner, 1914 pages 42-43). Psychologist Wilhelm Reich and some of Sigmund Freud’s acquaintances all had their first sexual experiences with prostitutes as young teens and this was not considered unnatural in their social milieu. (Both men were also likely sexually abused by their parents as children— very typical in sex-trade families.) Cigarettes and cigarette advertising were part of this conditioning.

[“Pre-Code” Hollywood ‘product placement’ for cigarettes. I suspect the “Cleopatra” image is probably later, though.]

Young boys were inducted into criminal lifestyles through the same tactics. On occasion cigarettes were adulterated with opiates and other highly addictive substances, thereby increasing the power of whomever supplied them. (Duke wasn’t the only guy willing to sell them at a loss!) The Ottoman Empire/Turkey, the supplier of high-quality tobacco and opium, was a long-time terminal of Galician network trade. By making the trade in cigarettes more difficult, lawmakers took a step undermining this criminal gang’s recruiting efforts.

19th century Americans were not ignorant of the situation described above. It’s no accident that the civic organizations which organized against human trafficking also organized against cigarette smoking (e.g. the Womens Christian Temperance Union). To James Duke, the battle was changing public perceptions of cigarettes from “little white slaver” to “torches of freedom”.

Duke used Sigmund Freud’s American representatives to change these public perceptions, by way of newspapermen/ ‘astroturfers’, particularly William Wesley Young. Yeah.

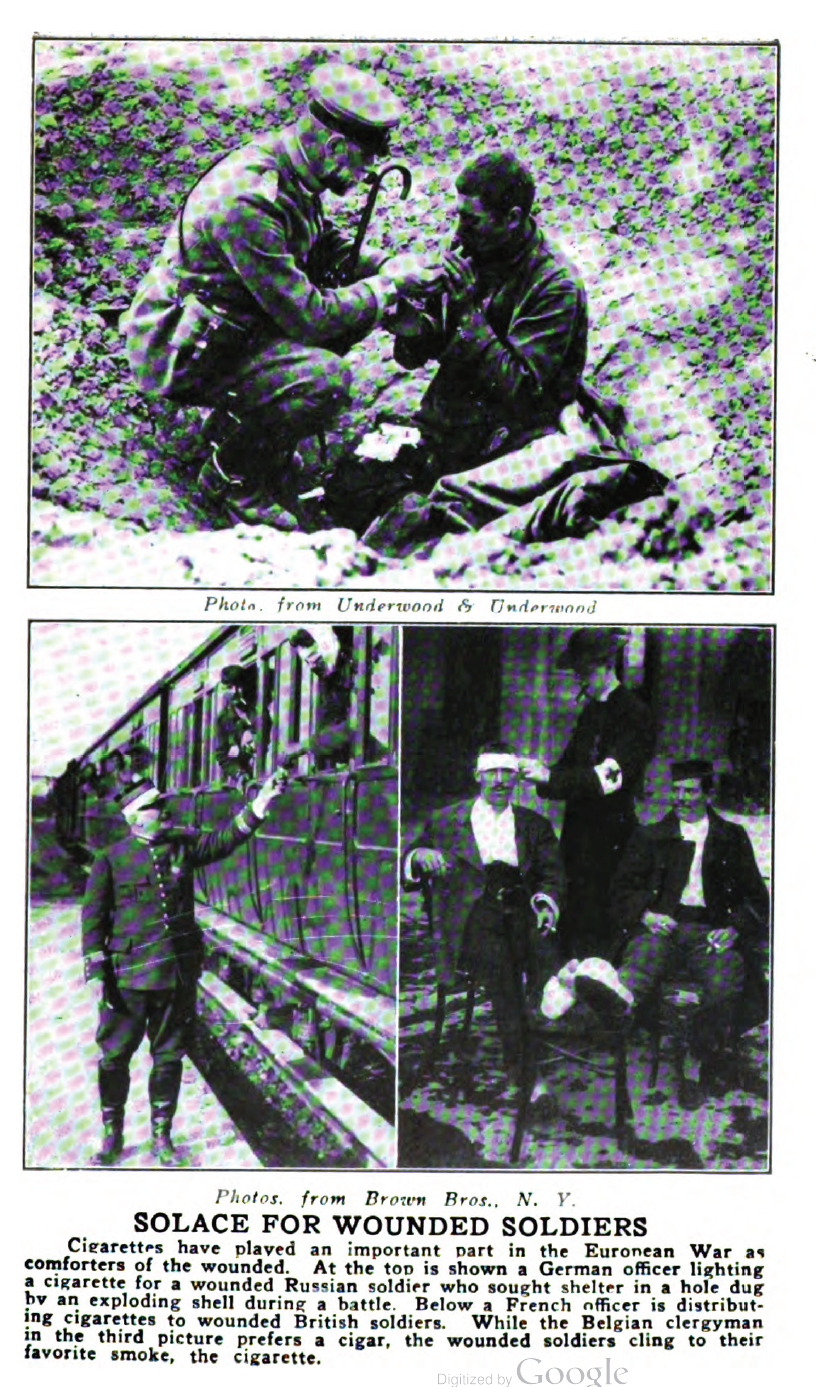

In order to achieve this “torches of freedom” transformation American Tobacco executives, like Benjamin B. Hampton and George Washington Hill, employed hacks like William Wesley Young to marry military-industrial-interests to tobacco-monopoly-interests via the WWI effort. Hence, The Story of the Cigarette (1916) pictured above, which focuses heavily on the “benefits” of cigarettes to soldiers on both sides of the WWI conflict. (The US hadn’t chosen which side to fight on when Young’s book was written.)

ENJOYMENT: Image from William Wesley Young’s 1916 “The Story of the Cigarette”.

COMFORT: Image from William Wesley Young’s 1916 “The Story of the Cigarette”.

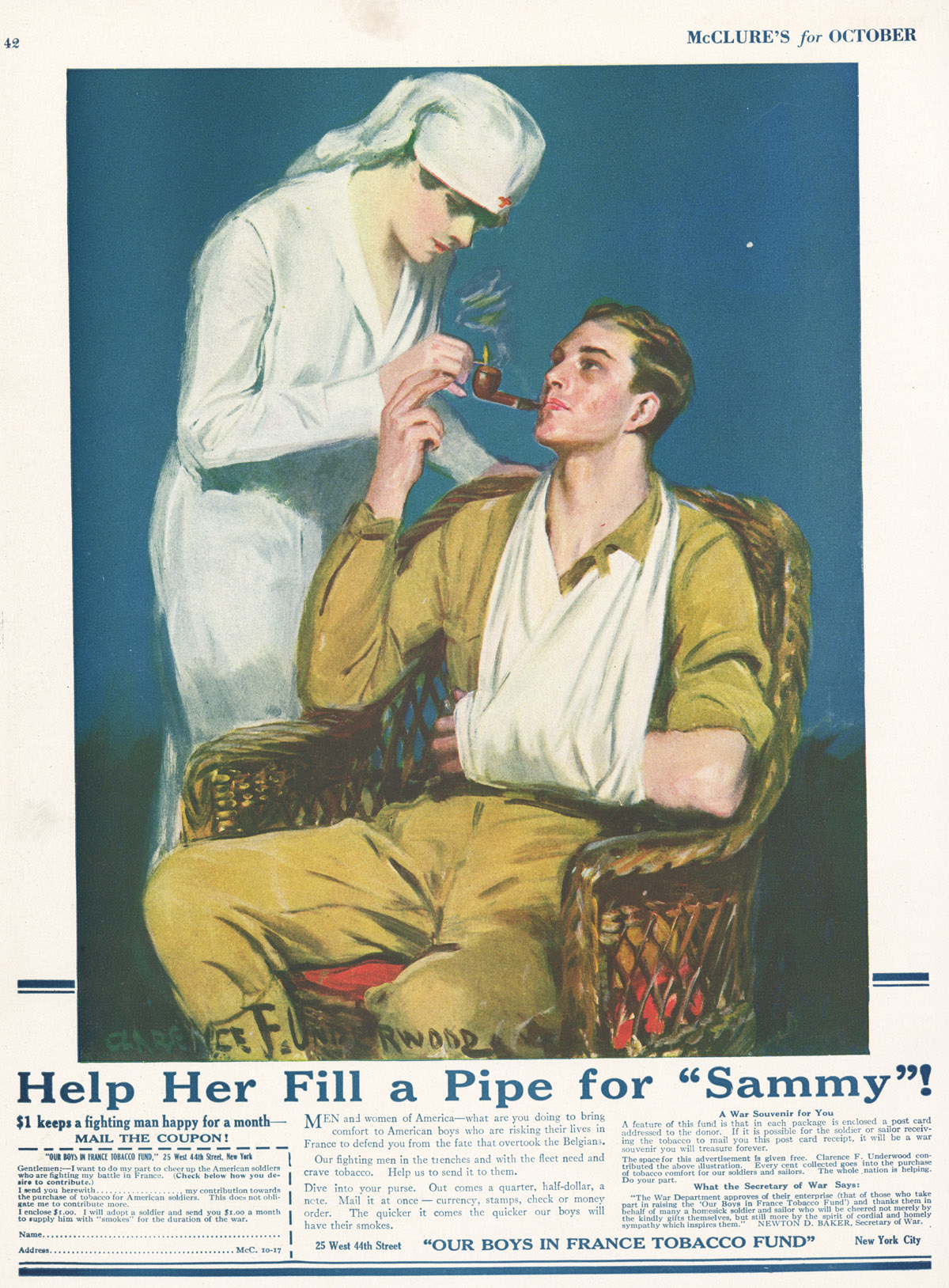

ENJOYMENT and COMFORT: Our “Homesick” Boys in France Tobacco Fund: this 1917 ad from McClure’s Magazine shows the Secretary of War, Newton D. Baker, stumping for the tobacco industry, wherein Duke was still a major player. Theodore Roosevelt and his allies in the film industry also supported the fund. Note how the word “Cigarette” is not mentioned.

By 1921, William Wesley Young was shepherding a sort of think-tank on “educating” the public with films. He sat alongside A. A. Brill on the “Educational Film Magazine” Committee on Pedagogical Research in Visual Instruction. Brill was the man responsible for establishing “psychoanalysis”, a pseudo-scientific mental health treatment/cult around the person of Sigmund Freud, in US mental health circles. “Educational Film Magazine”, a NYC-based publication, was run by a Jewish man of Southern extraction named Adloph “Dolph” Eastman (1878-1929), surname at birth “Eiseman”, from the area around Natchez, MS. Eastman clearly had no problem making his publication available to tobacco interests.

Educational Film Magazine, January 1921

Dolph Eastman had no previous experience in film, publishing nor education that I could locate. Mr. Eastman’s family lived in or near Natchez from at least the time of his grandfather, who is buried in the “Jewish Hill” of the historic Natchez City Cemetery. Natchez’s Jewish community is a famous one in the pre-Civil War South because of its wealth, smuggling and the Atlantic Trade, which the Hapsburgs coveted. This embattled community’s most famous member was the Sephardic Jewish slave-trader and pirate, Jean Lafitte, also a some-time mercenary who would fight for the highest bidder.

Supposedly a portrait of Lafitte, “The Terror of the Gulf” and Mississippi pirate, forerunner to John Patrick Looney and, to a lesser degree, Leon Goetz.

In 1929, eight years after W.W. Young’s “Educational Film Magazine” partnership and shortly before Young’s retirement, that same vice-president of American Tobacco, George Washington Hill, hired Sigmund Freud’s representatives in New York City, Edward Bernays and A. A. Brill, to run a public relations campaign on behalf of the “little white slavers”. From the Museum of Public Relations’ website, circa 2014:

[BEGIN]

1929: TORCHES OF FREEDOM

[Mrs. Taylor-Scott Hardin parades down New York's Fifth Avenue with her husband while smoking "torches of freedom,"a gesture of protest for absolute equality with men.]

“Cigarette sales would soar if [they] could entice women to smoke in public.”

By the mid-1920s smoking had become commonplace in the United States and cigarette tobacco was the most popular form of tobacco consumption. At the same time women had just won the right to vote, widows were succeeding their husbands as governors of such states as Texas and Wyoming, and more were attending college and entering the workforce. While women seemed to be making great strides in certain areas, socially they still were not able to achieve the same equality as their male counterparts. Women were only permitted to smoke in the privacy of their own homes. Public opinion and certain legislation at the time did not permit women to smoke in public, and in 1922 a woman from New York City was arrested for lighting a cigarette on the street.

George Washington Hill, president of the American Tobacco Company and an eccentric businessman, recognized that an important part of his market was not being tapped into. Hill believed that cigarette sales would soar if he could entice more women to smoke in public.

In 1928 Hill hired Bernays to expand the sales of his Lucky Strike cigarettes. Recognizing that women were still riding high on the suffrage movement, Bernays used this as the basis for his new campaign. He consulted Dr. A.A. Brill, a psychoanalyst, to find the psychological basis for womens smoking. Dr. Brill determined that cigarettes which were usually equated with men, represented torches of freedom for women. The event caused a national stir and stories appeared in newspapers throughout the country. Though not doing away with the taboo completely, Bernays's efforts had a lasting effect on women smoking.

[END]

[Removing Ancient Prejudices: George Washington Hill was personally responsible for developing the “Lucky Strike” cigarette brand.]

Given William Wesley Young’s New York City contacts with men like Brill and the denizens of the New York Friars’ Club, it’s not so shocking to me that Duke’s heirs would hire the American wing of the “Freud Cult” to put a happy face on cigarette consumption in 1929.

There are other synergies as well. Much like William Wesley Young’s cigarette employers circa 1916, Freud’s European lieutenants were busy courting the Austro-Hungarian military for patronage. Sandor Ferenczi, the Freudian who liked to sleep with his patients and never fully rejected childhood sexual abuse as the cause of neurosis, was Freud’s point-man with military leaders. Ferenczi lead a network of young Jewish military doctors who acted as salesmen for the cult inside officer ranks. Had the war not ended in November of 1918, Freud would have become the Hapsburg Army’s number one military mental health contractor via his “psychoanalysis”. (See Meszaros, Ferenczi and Beyond.)

The only surprising thing about Freud’s military contracting work was that it took so long to materialize, because Freud’s world-view was entirely in keeping with that of the military’s officer class and had been for decades by 1918. This officers’ world-view was the product of sweeping social engineering policies on behalf of Emperor Franz Joseph, who essentially instituted a policy of replacing real aristocrats in the military with ‘diverse’ merchants and socially-aspirant commoners. Freud had over the previous three decades (1880s-1910s) built his reputation treating Vienna’s rich Ringstrasse Set (imperially favored merchants and bankers) for their neuroses. Many of these Ringstrasse families were Jewish transplants from rebellious Hapsburg borderlands and beneficiaries of White Slave trafficking. Some of them also ran remarkably ineffectual anti-trafficking organizations, while helping the traffickers colonize new markets. Ooops!

Sigmund Freud claimed to have begun smoking cigarettes in his early twenties— quite late— but he’d caught up to American progressives’ expectations by his thirties. (And cocaine wasn’t easy to get in the 1880s!) When this picture was taken Freud was already suffering from mouth cancer and would end up having large portions of his jaw removed.

I believe it’s also worth mentioning that— as far as I can tell— William Wesley Young wrote this cigarette swill from his office at the theatrical Friars Club, the premiere social club for theatrical men in NYC. Just prior, Young had been busy “educating” immigrant Jewish boys via his film A Boy And The Law (1913), made alongside the by-then disgraced fraudster (and very likely pedophile) “Judge” Willis Brown, a.k.a. “The King of Kids”. (Brown was made a judge in the Mormon stronghold of Salt Lake City before it was discovered he’d falsified his credentials.) Young’s fictionalized account of the life of Canadian immigrant William ‘Willie’ Eckstein focused on telling young Jewish kids that, actually, you can’t break the law in the USA without consequence. What a strange message for these young, vulnerable children.