The Miseducation of Leon Goetz

It goes without saying that adolescence is a formative time in a person’s life. I’ve tried to sound out the truth about Leon Goetz’s teenage years in order to understand how, at 19 years old, Leon was able to patent a state-of-the-art submarine escape pod (the first such device known to history) with a high-priced D.C. lawyer.

This search has lead me in odd directions, but the most fruitful has been simply to look at who Leon lived around as a teenager. I’m going to recycle my graphic from The British Connection: Persecuting Judge Becker to show who was watching this ambitious, extroverted kid as he grew up in Monroe, WI.

Leon’s dad, John Conrad Goetz, rented the basement shopfront below Arabut Ludlow’s bank, the leading bank in the county. Everybody in Green County owed Arabut money at one time or another and Arabut pressed his advantage. As family friends of leading Chicago merchants like Marshall Field and real estate developer Potter Palmer, the Ludlows were pretty much in a class of their own in our community.

In the very same building, but a couple of floors above John Conrad Goetz, the son of our longest-serving judge Brooks Dunwiddie (in office 1858 - 1898), the prominent lawyer John Dexter Dunwiddie, rented his office. You could say that the Goetzes lived ‘below stairs’ of the most powerful families in town.

A few doors West, above the sidewalk, lived the grocer Daniel Young. His boys had made themselves famous in New York City about the time Leon was born, so the Goetz children would have heard tales of the newspaperman’s and the cartoonist’s success around town growing up. Above Mr. Young’s store was the telegraph office, the most modern communication technology prior to telephones. The Goetzes could hear the footsteps of ‘success’ over their heads every working day. The boys would have seen these powerful men file into the Universalist Church behind the bank building every Sunday, where their wealth was celebrated and a non-traditional, humanistic, flexible relationship with God was preached. It all must have been tantalizing for a young person.

The successful men above Leon had something else in common too: a devotion to the cause of Imperial Britain that far outweighed their commitment to American democracy. You can read all about Daniel Young’s and the Ludlow boys’ WWI-era persecution of the peace-seeking Judge Becker here. Four years prior, Daniel Young’s oldest child William Wesley began his career as an espionage agent for British Intelligence, using McClure’s Newspaper Syndicate to stoke resentment between the various groups of US citizens (German, Irish, Jewish) in service of Britain’s wars.

Monroe’s Brahmins struggled to “love thy neighbor”, at least in regard to their fellow citizens with German last names. I encourage new visitors to read what happened when Green County voted 10-1 against joining WWI in our March 1917 referendum. These British partisans didn’t care who they trespassed against in pursuit of their political aims— even if the victim was a teenager.

There were plenty of teenagers to victimize. As the Ludlows, Dunwiddies and Youngs peered out their windows onto the pavement below, they would have seen striving young men like sidewalk-confectioner Paul A. Ruf (who’ll I’ll write more on shortly) as well as the Gruwell’s apprentice showman Leon Goetz.

“Before Paul A. Ruf opened his confectionery business on the southwest corner of the square, he ran a shoe shining and confectionery business on the northeast corner of the square. In 1904 the city’s youngest businessman refused to give up his stand at the corner where the Commercial & Savings Bank was to be located until B. H. Bridge arranged for Ruf to move his business to the southwest corner of the square where it is still operating. (2006) “ From Pictorial History of Monroe, Wisconsin by Matt Figi.

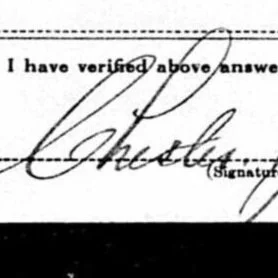

Which brings me back to Leon’s sub patent. Holding such a patent was not a politically safe thing for Leon. The USA was a strongly isolationist country and arming Britain with submarines could only be done on the sly by well connected people such as Mark Hanna. That somebody should have chosen Leon to be the ‘face’ of this dangerous undertaking suggests that by 1910 the North Side of the Square was already home to a siege mentality. I remind readers that John Dexter Dunwiddie’s brother William, the town clerk, was one of two people who had witnessed Leon’s sub patent application, the other being Mattie Matzke, who if I have identified her correctly, was about Leon’s age at the time.

But why choose Leon over somebody like Paul Ruf? The fact is that Leon’s family had suffered some public reversals in the previous years, of which the Dunwiddies would have been abreast. These reversals left young Leon in a position where he may not have had good guidance and felt stung by social disapprobation.

My sources for the following information are solely the civil court case records for Green County, which are held at the University of Wisconsin in Platteville. Leon suffered a series of traumatic events in the years immediately prior to his being recruited to hold the submarine patent in 1910. In 1903, Leon, Chester and their sister Muriel lost their mother Verena Hefti Goetz; the children were 12 years, 9 and five respectively. Their widowed father John Conrad, who was often too ill to work and who didn’t convalesce until 1915, was left to look after the three children with the help of Leon’s grandfather.

In October 1905, when Leon was 14 years old, his family life suffered another disruption: his grandfather Conrad sued for divorce from his wife Barbara. The court was specially convened in neighboring Rock County where Circuit Judge B. J. Dunwiddie presided. In 1905 there was little public acceptance of divorce, and the stigma would not have been lost on an intelligent teen. The circumstances surrounding the divorce probably didn’t help things either, as Barbara was found to have willfully deserted her husband more than one year previously, and was ordered to resume using her former name, “Barbara Burgy”. Details of Conrad’s statement, confirmed by Barbara’s brother John Luchsinger, say that Barbara ordered Conrad out of her home suddenly and no motivation was given for her behavior. (Judge Becker took John Luchsinger’s statement.) The pair had been married in 1901, although Conrad had lived in Monroe since 1861, which suggests that he came as a consequence of our first railway in 1857. Conrad Goetz was in his seventies at the time, Barbara in her sixties.

The damage from this disruption may have been deeper than what first appears. Leon was very close to his father— it was John Conrad who moved down to Florida first and Leon who followed shortly after in 1935— but there must have been times when young Leon felt more like the parent in their relationship. I say this because a second court case in 1916 raises questions about John Conrad’s judgement.

In 1916 John Conrad was sued by his girlfriend Pearl Blount for US$ 5,000 for failure to act on a promise of marriage in 1913. It appears that the case was prompted by John’s deeding his shop premises away to his children the year before. (By around 1912 the Goetz Tailor shop had moved catty-corner across 17th Avenue to a building adjacent to the Commercial & Savings Bank— about the location of Ekum Abstract and Title today.) One “Mr. Sherron”, who is never identified and his relationship to neither John Conrad nor Pearl is explained by court records, had approached John Conrad to settle the case on behalf of Pearl in the wake of this deeding.

This is the Commercial and Savings Bank which was once located at the North East corner of Monroe’s downtown Square. The Ludlow bank would have been across the street to the West. (West is LHS of this picture— the two windows on the left of the main entryway would have looked on to the side of Arabut’s bank, which the photographer must have stood in front of to take this picture.) John Conrad Goetz had bought the small building adjacent to the C&S some time prior to 1915. He began living with this two youngest children (Chester and Muriel) above this shopfront around 1912.

A close up of the building which either was, or would soon become the Goetz Tailor shop. John Conrad and his youngest children would have lived in the apartment behind the three top-floor windows. Judging by the picture of Paul Ruf above, Paul may have had his “shine artist” confectionary stand outside the Goetz’s Tailor building.

Suing for failure to deliver on a promise of marriage was not a common practice in Wisconsin, where then as now, if engagements didn’t pan out, both parties simply moved on with their lives. John Conrad’s testimony sheds some more light on the situation:

Q [questioner]: When you conveyed the property to your children, did you convey it for a consideration? What was the purchase price?

A [John Conrad]: I just simply willed it to them. I gave it. My son-- that is my way of doing business. My son, before he became of age, I gave him $1000.00 and the other one the same way, because they were boys that had lost their mother, and they tried to make their way. They had to get out and hustle to make their living and my health was poor; I had been under the doctor's care for a long time. I went to Waukesha, and I went to--

Q: I don't care anything about that. You conveyed it to them after you stopped going with Pearl Blount?

A: Conveyed it to them after I stopped going with her? I think I did.

Q: When did you become acquainted with her?

A: I couldn't say, I have known her for a long time. She worked in the shop for a while and I have known her since she was a little girl you might say.

Q: For a great many years?

A: Yes it was a good many years.

To clarify here, Pearl was somewhere between 35-40 years old when this courting happened, John Conrad testified that he thought she was "about 40 or 47 years old”. In the same testimony John Conrad gives Leon’s age as “about twenty two years old”; Leon was almost 26 at the time. This US$ 1000.00 mentioned by John Conrad might have been used as seed money when Leon took over the Gruwell’s movie theater in 1916, though it was probably not the full purchase price of their business.

The Gruwell movie theater couple, previously of Iowa and by 1916 in the employ of the Shallenberger Brothers and John R. Freuler, head of Arrow Film and its parent company Mutual Film, had moved to Monroe, WI sometime between 1910 and 1914 to run a movie theater. Mrs. Gruwell was the driving force behind managing the picture house; she and Leon would travel the Midwest attending industry conferences. It’s very likely that in 1912 when John Conrad dated Pearl he took her to the very theater wherein Leon worked:

Q: Do you remember meeting her [Pearl] at a theatre in December 1912 in Monroe?

A: At a theatre? Yes, I think I did.

Q: Do you remember calling the next Sunday at her house?

A: Yes sir.

Q: That is the first call you made on her at her house?

A: Yes sir. I think so.

Q: The first evening call?

A: I could not say whether it was in the evening or day time; I think I called in the day time.

Q: And after that you frequently called to see her?

A: Sometimes I went there once a week, sometimes two or three times a week, and then at times I didn't go there for a number of weeks.

John Conrad’s interrogator is stressing the movie theater aspect of Pearl and John Conrad’s courtship because dark movie theaters were known to be places couples would go to canoodle; they were also a favorite venue for prostitution. The lawyer is insinuating that exchanges were made in anticipation of marriage.

Q: And from that time on until the spring you called on her and took her to theatres?

A: Occasionally, yes.

Q: And lectures?

A: I don't remember the lectures.

Q: Well other places of entertainment?

A: Yes, occasionally.

Q: You invited her to go and went for her at her home?

A: Yes sir.

Q: Went to the moving picture shows? And from December until along in March you paid attention to her entirely so far as calling on any other woman is concerned?

A: I called on her, and I didn't go to see anyone else at that time.

It seems that John Conrad’s taking Pearl to the movie theater prompted Leon and Chester to caution their father against involvement with Pearl:

Q: During this time did you talk with her in regard to your family, your children objecting to your getting married?

A: She would speak about my children and how they liked her, and I told her they didn't like her and I never could get married under the circumstances; that it was just that it would never do.

Q: And when do you remember of telling her first?

A: Oh, I couldn't just state the time. We went down to the show and my son didn't want me to go to the show any more with her, and they got to talking, both the boys talked to me, that they didn't want me to go with her; for some reason they didn't like her, and so I quit going with her.

Q: That was on account of the objections that your children made?

A: Not exactly, no sir. I got so I didn't quite like her disposition myself.

Q: Did the objections your children raised have anything to do with it?

A: Yes, in a way. If it would displease my children-- why, I always liked my children, and I would not do anything that would displease them.

Q: And your children thought that you were paying pretty close attention to her?

A: Yes, they thought I had better quit.

Q: They thought you were going to marry her?

A: I don't think they did.

Q: You just said that they raised objections?

A: They thought I might get married.

According to Pearl’s lawyers Conrad Goetz, Leon’s grandfather, had threatened to cut John Conrad out of his will if he married Pearl. According to John Conrad, both his sister and his sister-in-law expressed that they “didn't like to have me go with that lady”. Pearl left a negative impression on the other Goetz family members, but exactly why was left unsaid. John Conrad blamed his change in feelings for Pearl on a negative comment she made regarding her neighbor, Jim Fidler, and his fence. Fidler was one of John Conrad’s friends.

It is here where questions about John Conrad’s judgment become paramount, because it turns out that he had reasons to question Pearl’s “disposition” well before his boys confronted him about it. Pearl had a habit of traveling to Chicago once a year, “during the season”, where she would make dresses. During this time, she would take a room at a “girls boarding school” and visit a type of rooming house run by a couple named Altenberg. The Altenbergs made a room available for Pearl and John Conrad when he would come to Chicago to visit her during these yearly trips; apparently she couldn’t have trysts with John Conrad at the “girls boarding school”.

There are aspects of Pearl’s story which do not make sense. The operators of legitimate boarding schools do not run them as hotels or hostels, precisely because their ability to operate depends on parents’ confidence that the girls are safe and not exposed to unknown influences. A “girls boarding school” which doubles as a rooming house for itinerant seamstresses is something else entirely. That John Conrad would visit Pearl during her periods working in Chicago and sleep with her at the kind of flop house the Altenbergs ran, while making promises of marriage he did not intend to keep, suggests a serious lack of judgement on his part.

Having been informed of his family’s reservations about Pearl, and having made up his mind not to marry her, John Conrad did not break off their relationship. He continued his visits, just less regularly and tried to hide their relationship from the public:

Q: You went out to get her that evening [July 4th] to come down town?

A: Yes sir.

Q: You took her around, walked down town, took her arm?

A: I don't know whether she took my arm.

Q: And you went down towards town, and when you got where the crowd was, you released her arm?

A: Yes sir, that may be.

Q: And you fell back when walking around town, instead of walking with her; you fell back, didn't you?

A: I had to do that to get through the crowd.

Q: You seemed to want to follow her around but didn't walk with her?

A: Yes, I walked with her.

Q: Took her to an ice cream parlor?

A: Yes Sir.

Q: Whose ice cream parlor?

A: I think the man's name was Hutch.

Q: That was the new ice cream place a little bit out on the side?

A: No sir on the south side of the square.

Q: It was not the popular ice cream parlor?

A: It certainly was; we were standing on this corner in the park.

Q: That is what she complained about in that letter, about your evading her, walking behind her. Isn't that the thing she spoke about in that letter?

A: No sir, she didn't say anything to me about walking ahead of her. There was nothing of that kind in the letter.

Q: You wrote a letter to her just before this, didn't you?

A: I may have, yes sir.

Q: You spoke to her cheerfully while you were going down town?

A: Yes sir.

Q: And she was pleasant and cheerful wasn't she?

A: Yes sir.

Q: And being so different when she got home? You spoke about that in a letter? What made her so different after she got home?

A: I don't know.

Q: Didn't she tell you it was on account of your treatment to her, going behind her, letting her go ahead, so that you would not be seen with her in public?

A: Well that would have been a pretty hard thing to do, to take her down town and not want to be seen in public with her. I would have left her at home if I didn't want her to be seen.

Q: That is why she says this. Speaks of it that you didn't want to be seen with her in public places, or something like that. She talked with you about it, didn't she, about the way you treated her?

A: No, she didn't seem to want to talk about that letter.

Q: After the 4th of July when you went to see her, didn't Pearl Blount talk with you about the manner in which you treated her in the park on the 4th of July?

A: I don't remember that.

…

Q: You kept on going with her after that?

A: Off and on, yes sir.

Whatever Pearl Blount’s faults may have been, John Conrad did behave towards her in an exploitative way, and in a way that— despite John Conrad’s testimony— was inconsiderate of the rest of his family’s feelings. As Leon’s father behaved like this well into his forties, it is only reasonable to assume his personality was similar when Leon was growing up. In modern psychological parlance, when a child is forced to take on the role of caregiver towards an egotistical parent it is labeled “parentification” and is considered a type of emotional abuse. This dynamic could only have added to the stress placed on poor Leon, who would have to “hustle” under the burden of his caregivers’ sickness and drama.

When Leon took over the Gruwell’s movie theater business in 1916— around the time of Judge Becker’s anti-war activism— the first movie he played at his theater was Teddy Roosevelt’s war propaganda epic “The Battle Cry of Peace”. This film was a very strange choice for a community which would vote 10-to-1 against joining WWI in a few months’ time. However, if the Ludlows or Dunwiddies needed a “face” for their unpopular war propaganda it would be quite natural for them to turn to a young man whom they had successfully exploited before. If Leon did take out a loan to buy out the Gruwells’ business, the Ludlow bank would have been the natural place to go.

The perpetrators of crimes against children are very often adept at manipulating children’s psychology. Traumatic events in childhood can cause childlike attitudes to persist well into adulthood and often the victims of abuse become abusers themselves later in life. While I can’t excuse some of the choices Leon made later in his life, I personally feel a great deal of sympathy for what Leon went through in his formative years. While he participated in the exploitation of teenage Edith May, and most likely that of other teens through his and his partners’ “health films”, he too was the victim of exploitation during a very difficult time in his life.

“For unto every one that hath shall be given, and he shall have abundance; but from him that hath not, shall be taken away even that which he hath.”