The Mutual Film Corp. Shallenbergers

In this post I’m going to cover circumstantial— circumstantial— evidence that the Shallenberger brothers, investment partners to John R. Freuler, Charles J. Hite, Harry Aitken and ultimately Otto Kahn, were involved in organized international prostitution, otherwise known as the White Slave Trade. While the evidence herein is circumstantial, I believe en masse it is revealing about the source of Mutual Film Corporation funds.

The Shallenberger brothers were hugely important to the development of early cinema in the USA, yet their contribution is usually glossed over because of the more charismatic personality of Charles Jackson Hite. Hite relates to our Monroe Mogul John R. Freuler because Hite joined Freuler’s Mutual Film in 1912, an organization designed to protect these men’s business against the Edison Trust . Hite brought his major investors, the three Shallenberger brothers— Dr. William Edgar, Dr. Wilbert and Dr. John Franklin— with him.

Hite’s own firm, C. J. Hite Moving Picture Company, was founded in 1906, the same year as Freuler’s Western Film Exchange, however Hite’s firm struggled for lack of capital. In 1908 help came in the form of his childhood friend William Edgar Shallenberger (or Wilbert, sources differ), who brought in crucial investment money from all three brothers. The three Shallenberger brothers were all itinerant medical doctors. Yes, itinerant.

Right here is where this post brings something knew to our understanding of Hite, Freuler and their crowd, because the Shallenbergers were medically trained, yes, but they weren’t typical doctors as histories usually imply. They were part of that class of questionable medical practitioners that the then-nascent medical profession and lawmakers struggled to regulate. One of the ways communities tried to regulate them was by requiring such doctors to register and pay a fee to practice in a given area. From Clinton Matthew Sandvick’s dissertation “Licensing American Physicians: 1870-1907” (2013):

The Sacramento Daily Union generally supported the passage of the state licensing law, but its editors expressed a few misgivings. The Union was concerned that the provision requiring itinerant physicians to pay one-hundred dollars a month was potentially unconstitutional, but the Union still supported the measure because it attacked that “class of swindlers.”

From at least 1910, two years after their initial investments with Hite, all three of the Shallenberger doctors registered with the state of Iowa as itinerant doctors:

Iowa Report of the State Treasurer for the Biennial Period 1914-1916. All three Shallenberger brothers appear in this record since 1910, but may have practiced as itinerant doctors earlier. As readers can see, there weren’t actually that many of these doctors in Iowa— at least practicing legally.

Did the Shallenbergers correspond to that unflattering description “swindlers” used by the Sacramento Union Daily in the 1870s? Well, here’s a newspaper ad taken out in the Manchester Democrat of Iowa, September 21st 1910:

Image from the US Library of Congress. Manchester Democrat. [volume] (Manchester, Iowa), 21 Sept. 1910. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

There are several points of interest in the above information. Firstly, we know that Dr. Wilbert Shallenberger (at least) specialized in sexually transmitted diseases. Secondly, at this time both Chicago and Waterloo, Iowa had remarkable red light districts. Thirdly, up until the end of WWI, medical doctors controlled the dominant international prostitution network that was based out of the Austro-Hungarian territory of Galicia.

I’m going to explore each of these points in a little more detail now, but I would like to alert readers to the fact that in 1914, the year of Hite’s suspicious death, Hite, Freuler and the Shallenbergers opened an equally suspicious spa/cabaret/bar/movie theater/dance hall/restaurant/??? in the heart of Ziegfeld territory. The Shallenbergers had also recently acquired the assets of the “Ziegfeld competitor” Shubert-family’s agent in Milwaukee, Edwin Thanhouser. Thanhouser owed his fortune to Shubert patronage:

Edwin traveled to New York in 1898 where he interviewed for an acting position with the Shubert brothers, but his business acumen impressed the Shuberts more than his acting ability, and he was instead offered a position managing the Academy of Music Theatre in Milwaukee, Wisconsin (L. Thanhouser 1970, 11). Edwin accepted the offer and moved to Milwaukee where he managed a theatrical stock company… Beginning in the 1890s, short films were used as fillers between acts. Over time, the program of Thanhouser’s Academy of Music tended toward more sophisticated fare, presenting the works of Shakespeare such as “Othello,” where well-known actors were sometimes secured as guest stars.

Using the wealth he accumulated in Milwaukee from the Academy of Music Theater (designed by Edward Townsend Mix, architect of Monroe’s original Methodist Church, now Arts Center), Thanhouser founded Thanhouser Film, one of the leading independent film companies capable of challenging the Edison Trust’s products. From thanhouser.org:

In 1909, Edwin Thanhouser, who had made a sizable fortune managing the Academy of Music Theater in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, decided to enter the motion picture business. At that time, the motion picture business was in its growth period, the fame of Hollywood and California was not even dreamed of, and New York City and Northern New Jersey represented the center of business in America….

Entering the business was no easy matter for Edwin Thanhouser or anyone else in 1909. America was a free country, but that freedom did not exist in the field of motion picture production. For a number of years the industry had been the private preserve of American Biograph, Edison, Vitagraph, Selig, Lubin, and a handful of other pioneers. Seeking to exclude others from entering what was becoming a growing and profitable business arena, the leading companies buried their differences and combined into the Motion Picture Patents Company, which was incorporated on September 9, 1908 and announced to the trade on December 18 of the same year… Members of the combine referred to as the "Trust" or "Patents Company"

Culminating in 1910— the year after Thanhouser started his film company— the Shubert brothers broke the monopoly on the theater-management industry enjoyed by the Theatrical Syndicate, which was controlled by Ziegfeld investors Abe Erlanger and Marc Klaw. The Shuberts did this through a strategy of ‘collecting actors’— controlling theatrical talent— which starved the Syndicate of performers. (Perhaps Flo Ziegfeld took notes?) The Shuberts then set up their own monopoly The Shubert Organization, which was based in New York City (Broadway), but the family owned theaters across the country. Austro-Hungarian police identified traveling international musical acts as one of the main vectors through which human trafficking for the White Slave Trade (organized international prostitution) was effected— such trafficking would have to have piggy-backed off of these theater monopolies.

I’ve talked about Chicago’s horrific red light district and the patronage the sex trade received from powerful politicians elsewhere. The situation was so awful— even by contemporary standards— that it inspired W. E. Stead’s expose of the White Slave Trade, and particularly the organized exploitation of female children, titled If Christ Came to Chicago. The brothels of Waterloo, Iowa are less studied than those of Chicago, but circumstances suggest further attention is warranted. The following is from the National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form filed by The Louis Berger Group Inc. in July 2014 for their properties in downtown Waterloo:

A number of hotels were clustered on the west side of the river in the late nineteenth century, influenced by the location of the BCR&N Railway passenger depot at 605 Bluff Street. These included the Western Hotel on the 300 block of West 4th Street (between Jefferson and Washington streets) by 1885 and, just around the corner at 14 Jefferson Street, the De Sota Hotel by 1892. Hotels located near the railway depot were also well known for the unsavory elements that were attracted to that area. The Globe Hotel, which was located at 610-614 Sycamore Street, was shut down in 1904 after a police raid for prostitution. The hotel seems to have reopened because the new proprietors were cited the next year for "keeping a disorderly house." Later the Windsor Hotel, located just a half a block down , was also raided for suspected prostitution . With all the new workers coming into Waterloo and the travelers passing through the city, these types of businesses were provided with plenty of customers (Full and Price 201 O:Sec. 8, p. 40, note 31 ).

What The Louis Berger Inc. representatives document about the synergies between the railway and bordello prostitution is absolutely typical of the Galician network in the USA, Europe and far beyond.

In 1910 economic conditions in Waterloo were not good, and a significant population of African Americans were brought in by the railway to suppress the wages of its existing Caucasian employees. This labor-suppression tactic was typical of the ‘robber baron’ social set and its use predates the Civil War. From Niria White’s “African American Labor History in Waterloo”:

While these laborers took the jobs offered to them, many were denied housing. Some of the first black laborers who arrived in Waterloo lived in train cars near the Illinois Central train yard. Waterloo is split up by the East (north) and West (south) side by Cedar River. Downtown Waterloo along with a number of manufacturing plants sat on the banks of the Cedar River as it meanders south. African American were allowed to live in a small area next to the Illinois Central tracks called Smokey Row. Roughly twenty square blocks in total, the district was filled with saloons, prostitution, and dope dealers. Despite its condition, black laborers moved into Smokey Row due to a lack of housing elsewhere in Waterloo. Although Smokey Row was technically the only place that allowed for African Americans to live, there were many cases where African Americans lived outside of this area.

It seems that Waterloo developed a thriving sex-trade sub-culture that existed well into the 1960s, because it was in Waterloo that serial killer John Wayne Gacy first came to police attention. Gacy was involved with local pimps and pornographers when he was first convicted of raping a 15 year old boy. The commercial sex subculture in Waterloo must have been remarkable for a town of 70,000 people to have attracted someone like Gacy. The town certainly attracted VD specialist Wilbert Shallenberger decades before.

A ‘hot topic’ among scholars studying prostitution is the medicalization of the sex trade that happened at the end of the 20th century. State-sponsored prostitution— bordello prostitution, which created the bulk of demand for human trafficking— required a ‘fig-leaf’ to be acceptable in any way to the populations living where it was tolerated by authorities. The medical profession supplied this leaf. Supporters of bordello prostitution in Austro-Hungary, and other states where bordellos were tolerated/legal, claimed medical supervision of state-licensed prostitutes in state-inspected bordellos would protect both sex workers and limit the spread of VDs. Of course, this was hokum, but it did give well-connected doctors an ‘in’ to the Galician network. Eventually, the network came to be dominated by medical doctors, who mediated between the gangsters and their state sponsors.

But what does “dominated” look like in practice on the streets? According to historian Edward Bristow, in 1896 leading participants in NYC’s sex trade incorporated their own mutual support society: “New York Independent Benevolent Association” (IBA). Bristow quotes Helen Bullis’ 1912 description of this organization:

“a Jewish mutual benefit society, including among its members practically all the Jewish disorderly house keepers of prominence in New York. To say that it is composed wholly of such persons or of “white slavers” is an exaggeration, but it is strictly within the truth to say that most if not all its members are engaged in occupations which in some way touch or depend upon prostitution for their support. This would include keepers of cafes patronized by pimps and madams, clothing dealers selling to disorderly houses; doctors who attend inmates of such houses; saloon-keepers in certain districts; professional bondsmen and many others.”

Bristow himself clarifies the situation further:

“It [the IBA] functioned as a private economy such as existed in the other centers of Jewish vice, and because there was no state regulation [in NYC], the doctors played a big role in the organization. Dr. Solomon Newmann, a highly respected Lower East Side physician, asserted in 1909 that 80 per cent of the prostitutes in New York suffered from venereal disease. Madams and pimps wanted to protect their investments and clients grew accustomed to seeing medical certificates, several of which survive, testifying to the good health of their partners. A number of local physicians were notorious for specializing in this lucrative practice. After Dora Rubin had escaped from Mendel Schneiderman's clutches she deposed that she had been examined by several doctors, including Joseph Adler. Based in Columbia Street, Dr. Adler was reputed at one time to be president of the IBA.”

In Austro-Hungary, doctors who specialized in ‘skin diseases’ (what we would call sexually transmitted disease today) disproportionately came from the same ethnic background as the families of the Galician network. It was these doctors who were in demand by politicians and police who sought toleration and regulation of brothels.

The Shallenbergers were extremely well capitalized for the type of doctors who merely peddle their services between hotels: it was Shallenberger money that allowed Hite to compete in a capital-intensive business. Their Chicago-Waterloo axis of operations put them in an excellent position to benefit from the Galician network, if this was in fact the source of their capital. I was not able to find any other reference to the medical careers of these brothers other than the itinerant licensing and advertising information above.

Illinois Central Corporation 1996 Annual Report. Illinois Central Railroad. 1997. The Red line is called the “Sioux City and Pacific Railroad” today.

The Galician network was run on a family-relationships basis, and it seems the Hite/Shallenberger film company was run a similar way: despite having access to Chicago’s huge film labor and capital market, Hite looked to his Lancaster, Ohio boyhood friends for money. What can we say about the Shallenberger Family?

While Hite’s family was a transplant to Lancaster (city), Ohio from Virginia; the Shallenbergers were among Fairfield County, Ohio’s earliest settlers. Lancaster was and is the principle town in Fairfield County. Lancaster suffered from some of the same problems that Waterloo did:

The Police Department Begins [early 1900s]

During the early days of the police department its officers spent considerable time in the "hop yards," a notorious section of the city's [Lancaster’s] East End which contained many saloons and brothels. This area generated thefts, murders and prostitution complaints, which had to be investigated by the police.

The Shallenberger brothers’ father was Theodore "Theo" Shallenberger (1851-1916), who had married Cornelia Ellen "Nelia" Bechtel (1855-1910) in 1874. Theo was respected as the county’s commissioner, a horse-breeder, and probably a cigar merchant too.

A diagram showing the direct ancestors of the Shallenberger brothers.

Excerpt from “Lancaster and Fairfield county Ohio”, 1901

Politics was an early victim of international organized prostitution in the USA and Austro-Hungary, as pimps organized massive voter fraud systems based out of “tolerated houses of prostitution”—they literally had the power to deliver an election. In the democratically-minded USA, voter fraud was a network specialty, with the pimps favoring different parties in different places. In NYC it was the Democratic party which enjoyed the pimps’ largess; much like it was the Democratic party who were receptive to voting-block offers from cult-leader Mischa Appelbaum. At this time, the duties of a county commissioner often included overseeing election procedures, so Theo Shallenberger was in a good position to make interesting contacts and pay for expensive hobbies.

While Lancaster was the birthplace of the Hite/Shallenberg partnership, the boys carved out their own business niche in Waterloo, Iowa. Certainly, there was something about Waterloo that made Hite feel very safe. While working out of NYC and Chicago, Hite and the three brothers hired Waterloo boy-wonder William Ray Johnston to be their right-hand man. Johnston would marry Hite’s daughter Violet shortly after being brought into the team.

Hite looked to Waterloo for other things too, as reported in Motography, August 1912:

Two years after this was printed, Hite died in an unexplained automobile accident in NYC. Given his odd death, Hite’s insistence on importing a Waterloo car suggests eerie forebodings of gangland-style foul play. Is such foul play even remotely possible? Given the encroachments Hite and the Shallenbergers made onto Ziegfeld territory in NYC, I would answer “yes”.

Motography magazine was published by the Chicago-based Electricity Magazine Corporation, which published many different types of medium on electrical gadgets and systems. The Electricity Magazine Corporation seems to be a shell, however, there was only one supplier of electric power in Chicago: the Commonwealth Edison Co. Edison, of course, headed the Edison Trust which independent film producers like Hite challenged. Neither Edison, nor any of the independents, would balk at illegal acts to protect their businesses. Motography’s loud interest in Hite’s automobiles— an Achilles’ Heel— wouldn’t have been missed by any of Hite’s enemies.

Finally for this post, I’m going to look at the Broadway cabaret/movie theater that Hite, the Shallenbergers, and their partners from Mutual Film were in the process of opening when Hite died: The Broadway Rose Garden. This place was supposed to have a variety of high-class entertainments that competed for the same “tired businessman” crowd to whom Ziegfeld marketed his “Follies”. Thanhauser historian Q. David Bowers describes the Rose Garden as a “spa”; it was reported on as a cabaret (right next to Ziegfeld’s Follies!) in the news section of trade press; while the Garden’s own press releases emphasized its bar, variety show stage, movie theater, restaurant and dance hall facilities with professional dancers. Needless to say, the Garden was an ideal ground for higher-class prostitution, the presence of which is strongly suggested by the establishment’s floral name— the connection between flowers and female genitalia had been prominent in popular culture for a many decades by 1914. (For example, “Olympia”, a famous portrait/depiction of a prostitute by Edouard Manet from 1863 makes heavy-handed use of this flower symbolism.)

Moving Picture World, Sept 12 1914 1/2

Moving Picture World, Sept 12 1914 2/2

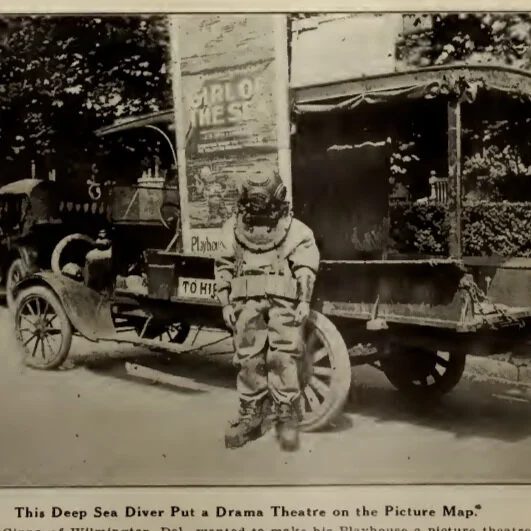

A jaw-dropping feature of the Broadway Rose Garden was its underwater film photography exhibit, which I will cover more in an upcoming post. Somehow, Hite got preferential access to submarine technology that allowed movies to be filmed under the waves. The technology was promoted in cooperation with the Smithsonian Institution, which also got preferential filming rights to Theodore Roosevelt’s African hunting adventures, to the chagrin of Col. Selig.

Moving Picture World, July 4th 1914

The Broadway Rose Garden never made it off the ground. Troubles with contractors began after US $200,000 had already been invested— another classic gangland tactic— and its opening had to be delayed. Then Hite was killed driving one of his beloved cars: Hite was known for his penchant for speed but this didn’t appear to be a factor in the accident, which was never explained. Dr. Wilbert Shallenberger— the VD doctor— rushed in to take over the management of the Broadway Rose Garden, but the venue went bankrupt by the end of 1914. By January 1915 it was under different management and by 1916 the property was slated to be converted back into a skating rink.

New York Clipper, July 25th 1914

As I mentioned at the beginning of this post, the evidence presented here regarding the Shallenbergers and the White Slave Trade is circumstantial and does not conclusively prove their guilt. However, there are a lot of uncomfortable facts that point in that direction. After all, Freuler got his start in film running a theater that he was ashamed to tell his friends and family about— what sort of partners would such a man seek out for bigger and better things?

![Image from the US Library of Congress. Manchester Democrat. [volume] (Manchester, Iowa), 21 Sept. 1910. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5dff6acf9e828d1b25fc48be/1604844948168-U5J95FMOHIBILEL5RYRB/Manchester+Democrat+Iowa+Sept+21+1910.png)