The Mutual Film Corp. Submarine Connection

One of the strangest aspects of film entrepreneur Leon Goetz’s life is the submarine escape pod patent he filed when nineteen years old— the patent was awarded in 1910. The existence of the sub patent did not make it into Goetz family lore, instead the descendants of Leon’s brother Chester were told that Uncle Leon took out a movie projector patent, the proceeds of which funded the 1931 Goetz Theater. (No such movie projector patent exists.)

Leon’s escape pod was “state of the art” for the early 1910s, according to submarine historians who examined the patent diagrams for me— which only adds to the mystery of how the teenaged son of a tailor from land-locked Monroe, WI became involved with such technology.

But Leon isn’t Monroe’s only submarine connection. Monroe-native John R. Freuler was connected to submarine technology through his 1914 business partnership with Charles Hite and the Broadway Rose Garden, which showcased bleeding-edge underwater film-making, as well as his 1916 “Secret of the Submarine”, a serialized film that was both pro-British and war propaganda. Both the Rose Garden and “Secret of the Submarine” were financed through the Mutual Film Corporation.

So Monroe’s submarine connection comes from two different angles— the teenaged Leon in 1910 and John Freuler in 1914 -16. Had John left Monroe and never looked back, I’d be tempted to say these two different sub connections were coincidental. But John did look back, at exactly the time he began investing in sub tech. The tricky thing is that by 1910 Freuler had been living in Milwaukee for over a decade— so any reasonable explanation of Leon’s patent calls for the involvement of a third party beyond these two men.

A clue to this “third party” lies in the business link between Leon and John Freuler: Leon’s ‘father’ in the movie biz, J. P. Gruwell. Whatever force brought J. P. Gruwell to Monroe is probably the same force that materialized a sub patent for Leon Goetz.

So how did this “force” affect the Gruwells? In 1910 J. P. Gruwell was still editing a newspaper in Dr. Wilbert Shallenberger’s Iowa territory, a territory in which the doctor used newspapers to advertise his services as a traveling venereal disease specialist. (More on that below.) Sometime between 1911 and 1914 J. P. Gruwell and his wife left Iowa and moved to Monroe, WI to try their hand at running a movie theater with no prior experience that I could find. While self-employed in this way, Mr. Gruwell became “connected to the Chicago office of Arrow Films”— trade paper The Moving Picture World reported this on December 1st, 1917 with no clear date associated with the event, but Arrow Film was founded in 1915, so it couldn’t have been earlier than then. (See image below.) Arrow film, a daughter company to Mutual, was managed by Freuler’s business partners the Shallenberger brothers, one of which was the V.D. doctor mentioned above.

Therefore, J. P. Gruwell had a reason to know Wilbert Shallenberger prior to Gruwell’s move to Monroe, WI; Gruwell probably knew Wilbert Shallenberger, and certainly knew of him, during his time in Monroe running his movie-house. Since Gruwell was still living in Iowa in 1910, his certain link with Mutual Film came too late to provide any further explanation for Leon’s patent.

Moving Picture World, December 1st, 1917. Mrs. Gruwell was the driving force behind the couple’s interest in film. She liked to work with other men, however. Leon and Mrs. Gruwell would travel the region together visiting trade association events while Mr. Gruwell appears to have stayed home. It seems that she picked up another satellite in Monroe besides Leon…

Given the extreme unlikelihood of more than one person from Monroe being involved in submarines in the 1910s, it’s probable that this “third party” had some pre-1910 connection with Mutual Film founder John R. Freuler, who in the 1914-15 period was studying how rural theaters were run in Europe. Freuler would have shared this business intelligence with his managerial staff and investment partners like the Drs. Shallenberger.

I think it’s more than likely that a Shallenberger recommended to the Gruwells that they set up their business in Freuler’s old home town as an experiment implementing what Freuler learned in Europe. The “third party” would have made a good contact to help the couple get established, and sometime during 1914-16 the pair picked up a trusted showbiz apprentice named Leon Goetz who already held a state-of-the-art submarine escape pod patent.

Frankly, the Gruwells had little other reason to move to Monroe to run a theater, as successful theaters already existed here. They also had little commitment to our community: by 1920 Mrs. Gruwell had moved to take up managing a theater in Grand Rapids, Michigan, while her husband J.P. had returned to the newspaper business in that state three years earlier— not long after being hired by Arrow. Fortunately for Leon, it didn’t take long to learn everything the Gruwells knew about the film business!

So, who could have been this “third party”? What would have put Monroe, WI on the map for people such as Dr. Wilbert Shallenberger and the Gruwells? Why would John R. Freuler ever look back?

In 1914 Monroe burst onto the awareness of the regional promotion/advertising scene with the “Cheese Days Festival” that Edith May’s uncle and members of William Wesley Young’s family first organized. Local scuttlebutt is that it was descendants of the English living in Monroe and nearby New Glarus who had the foresight to capitalize on the Swiss heritage of much of the local population for tourist reasons: those English would include the Young family, who ran the grocery store on Monroe’s Square.

William Wesley Young’s father certainly had more money than his occupation would suggest, as he bought an almond farm in Georgia and would take long trips down there to oversee it. Special connections would also explain Art and Will Young’s success in both the New York and Chicago publishing industries, and Will’s British Intelligence work. From 1900 the US lead in producing the type of submarine that the British Royal Navy was interested in buying— the “Holland” class— and its US manufacturer Crescent Shipyard in Elizabeth, NJ worked under British shipbuilder Arthur Leopold Busch (whose career had roots in Hamburg) to produce these remarkable boats. An English connection is the most likely explanation for Leon’s sub patent.

Can we learn more about this Monroe-based “third party” from the Freuler submarine side? As I mentioned, wild-card Monroe transplant J. P. Gruwell was employed in some capacity by the Arrow Film Corporation out of Chicago, which ran from 1915-26. Arrow Film was overseen by two of the Shallenberger doctors, William Edgar and John Franklin, whom I discussed in my previous post dealing with their probable prostitution connections.

The Shallenbergers’ business model was to employ men from the newspaper trade, like J. P. Gruwell, to write snappy scenarios for their film-products. In 1910, just prior to the Shallenbergers’ entry into the film business, J. P. Gruwell edited a paper in Maquoketa, Iowa— a railway town on the network between Waterloo, IA and Chicago, IL. Had Wilbert Shallenberger advertised his venereal disease treatments in the Maquoketa newspaper which Gruwell edited, he would have reached the central area covered by the network of tracks between Chicago and Waterloo, and the heart of the Iowa region wherein he practiced as an itinerant doctor.

Excerpt from”Iowa” section of “N. W. Ayer & Son’s American Newspaper Annual and Directory”, 1910. Published in Philadelphia, PA. “Excelsior” is the name of the paper, it went out on Fridays, had Republican political affiliation, was founded in 1836, had 8 pages with dimensions 17 by 24 inches, 1.50 is a subscription something (yearly price?) and 1,960 is a circulation number— most of the town read the paper.

To give readers a perspective on the area covered by the Goetz Movie Theater Empire in relation to the VD practice of the Shallenberger brothers, I’ve created the map below from an 1881 plan of the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railroad Company network. Blue stars represent the southern locations of the 1920s-era Goetz Empire, the Black stars (far left) show the Waterloo, IA station and (center) the Maquoketa station, when it was the terminal station for the still-developing ‘Davenport and St. Paul Railroad’ in 1881. To the extreme east and off the map lies Chicago, Milwaukee is roughly equidistant from Maquoketa but to the NE. The map shows the meeting corners of Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa and Illinois territories. Waterloo would have been at least a day’s train journey from Chicago, possibly two— the Goetz cluster-area would have been accessible in about 12 hours in 1910.

Close up from: G.W. & C.B. Colton & Co. “Map of the railroads and extensions of the Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul Railway Company.” New York, 1881. Held by the Library of Congress.

Full map from which the excerpt above was taken, the region containing both Blue and Black stars is circled. G.W. & C.B. Colton & Co. “Map of the railroads and extensions of the Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul Railway Company.” New York, 1881. Held by the Library of Congress.

Arrow was one of the production firms that supplied movies to John R. Freuler’s Mutual Film Corp, an exchange/production conglomerate. In 1912 Freuler and his partner Harry Aitkin took on the Shallenbergers, Charles J. Hite, Minnesotan Crawford Livingston and Otto Kahn as business partners in the formation of Mutual Film, which was designed to help them beat the Edison Trust. Edison legally controlled key technology for all parts of the movie industry. Aitkin was well connected in wealthy Republican party circles in Chicago; Livingston was a Minnesota magnate; the Shallenbergers probably ran prostitution networks in the area circled above; Freuler had Milwaukee (pornographic) movie biz and real estate connections; while Hite was clearly the fixer for ‘Back East’, where the big money (Otto Kahn), the military and most film technology was controlled. Across these businessmen, Mutual covered the heart of the wealthy northern Midwestern states and the pornography-prostitution-movie theater supply chain which distributed their “independent” (i.e. illegal) product.

Early on in this business partnership, Mutual produced films which I believe were Imperial German propaganda, specifically the Pancho Villa flick (1914) and the anti-war work The Birth of a Nation (1915). Mutual switched sides to producing British propaganda around the same time Col. Fayban did, 1916, that is when British Prime Minister Asquith croaked and Lloyd George changed Imperial British policies about carving up the Ottoman Empire. When Freuler and his team did get on the war train, they got on in a ‘submarine’ way.

In June 1916— fully six months before the USA’s entry into WWI— Freuler released his second serialized movie offering, which was about German spies and submarine technology: The Secret of the Submarine. The story was supplied by two Anglophone war correspondents— a journalistic position that was/is often used as a cover for espionage— and these two ended up in a legal battle over plagiarism.

Mutual’s submarine connection goes back to 1914 though, before their switch to producing British propaganda. When Mutual bought the Thanhouser Company, they acquired interest in Thanhouser’s partnership with the Submarine Film Corporation, which was founded by inventor John Ernest Williamson and his brother George. John Ernest was a newspaper cartoonist (just like Art Young) drawing for The Virginian Pilot in Norfolk, the Philadelphia Record and others. He began working on his undersea still photography as a “scoop” for the Pilot and was subsequently invited to present his work at the First International Motion Picture Exposition in New York City— before he’d even shot an inch of movie film! There he met “professors, movie stars, financiers, producers, photographers of still and motion pictures, cinema exhibitors”, according to his memoirs. He also found funding:

From “Twenty Years Under The Sea”, autobiography of J. E. Williamson. 1936.

Norfolk, VA became home to a US Naval base in 1915, one year after the events described above, and the US Department of Defense is now the primary employer in that city. But, despite what J. E. Williamson said on page 39, Norfolk city leaders were not the only investors he had— on page 41 he states:

From “Twenty Years Under The Sea”, autobiography of J. E. Williamson. 1936. Continued Below

From “Twenty Years Under The Sea”, autobiography of J. E. Williamson. 1936.

I’ll speculate that the New York “principal backer” was Otto Kahn as a representative of Kuhn, Loeb & Co. Edwin Thanhauser would be “the authority in the film business”. Whatever deal Thanhouser did with Kahn in order to invest in Williamson resulted in Mutual Film’s purchase of the Thanhouser assets later that year (1914).

The early Thanhouser/Williamson film (Thirty Leagues under the Sea, 1914) and the Mutual/Williamson films (Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea, 1916; The Submarine Eye, 1917) were fantasy features and not overtly war-related. However, these films did have interest for the US military, because the Williamson “photosphere” allowed filming from submarine boats. The construction of this “photosphere” was made possible by the financing described above. The apparatus was a huge, telescoping metal pipe with a glass dome on the end which could extend 250 feet into the sea. John’s father Charles had designed and manufactured an early version of the device for inspecting ships’ hulls, but John fitted a five-foot-wide glass observation chamber to the end of the pipe which allowed for movie-filming.

Thanks to Hite’s finesse, the first fruits of this Norfolk/New York investment were to be shown at Mutual’s Broadway Rose Garden as a loss-leader for the dancing girls, unfortunately this premiere was a victim of Hite’s contractor troubles. From Thanhouser historian Q. David Bowers:

Although The Moving Picture World announced that this film had been shown at the Broadway Rose Gardens, New York City, on Saturday, June 27, 1914, apparently this report was premature, and the scheduled showing did not take place at that time. Subsequently, the picture was shown privately at the Smithsonian Institution and the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. The first public showing is believed to have been at the North Avenue Theatre, New Rochelle, New York, on July 22, 1914. On August 6, 1914 approximately 300 guests invited by Charles J. Hite came to a special viewing of the film.

However, Mutual had bought something far more valuable than “Thirty Leagues Under the Sea”. When Mutual Film acquired Thanhouser, they also purchased access to decades of submarine film research and development data in an area of significant interest to the US Navy:

"George M. Williamson, treasurer of the Williamson Submarine Film Company, Norfolk, Virginia, has been in New Rochelle at the Thanhouser plant, which is to produce the undersea prints for the Williamson company, awaiting the return of Carl Louis Gregory, the first man in the world to take motion pictures under water. About 20,000 feet of undersea stuff was taken, and the first release will be a five-reel feature. This five-reel production, by the way, will be the culmination of 30 years' experimentation with the Williamson submersible tube. The Moving Picture World had a story on this remarkable expedition on April 25. Mr. Gregory has been absent for two months at Nassau, Bahama Islands, and returned on Wednesday, June 10." (From the Moving Picture World, June 20, 1914, quoted by Q. David Bowers)

The operations of the Williamson Brothers were of intense interest to the US State Department representative in the Bahamas, too:

"The unique work of Carl Gregory at the Thanhouser Company in making movies under the ocean is the subject of a report of the U.S. Consul at Nassau in the Bahamas. The New York Evening Sun is thus led to comment editorially on the feat: Mr. William F. Doty, our Consul at Nassau, has just reported the successful operation of a submarine motion picture camera recently invented by an American photographer. No machine previously invented has been efficient at a submersion of more than two or three feet, but with this apparatus submarine pictures have been taken in Nassau harbor showing with great clearness the marine gardens, fish of many varieties, old wrecks with divers working among them, anchors at a depth of a hundred feet, and the movements of sharks and other submarine dangers…

"Consul Doty reports that an American physicist of high reputation has expressed opinion that the tube may be lengthened perhaps to 1,000 feet, which would make it of importance in many lines of scientific work in oceanography. It may prove very useful in salvage operations and in the inspection and repairs of hulls at sea. In the pearl and sponge fishery the tube is expected to work a revolution, since many of the best specimens lie too deep for exploration in the diving helmet. These films have been shipped to New York, where they are to be placed on exhibition at once. No more interesting development of the cinematograph has yet been offered." (The New Rochelle Paragraph, July 10, 1914)

Mutual Film, a company at least in part financed by Otto Kahn who was suspected of lending to the Imperial German war effort, and a company open to making Imperial German war propaganda, had purchased submarine technology of interest to the US government. By the end of the year the man who brokered this deal, Charles Hite, was dead under suspicious circumstances.

If the US Submarine program has a political father, he is Theodore Roosevelt, who took a personal interest in developing and promoting sub tech from at least 1903. (When he was still open to taking Imperial German money.) Teddy had a great interest in film too, and was aggressive using the medium to market himself. The USA would use Teddy’s new submarines in battle under direction of his cousin Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who was assistant secretary to the Navy in “Little Tommy” Wilson’s administration. (The secretary was FDR’s long-time political ally Josephus Daniels.)

It’s hard to image a technology that would appeal to the Roosevelt Junta more than the Williamson’s underwater filming apparatus. In 1920— when Mutual began to have financial troubles— the Williamson brothers set up a research laboratory in the Bahamas, a group of islands that has since the 1940s at least attracted a great deal of Navy R&D money, for example the Atlantic Undersea Test and Evaluation Center, just 180 nautical miles west of what would become Meyer Lansky’s gambling/prostitution/pornography playground:

The Atlantic Undersea Test and Evaluation Center's detachment on Andros Island's main job is managing expansive test ranges so the Navy can conduct various underwater tasks, such as measuring the acoustic signatures of submarines and validating those signatures before deployments, as well as anti-submarine and electronic warfare research and development activities. (The Drive, Sept 6th, 2019.)

Undersea topography and resulting acoustical properties were of acute scientific interest during WWI, which was the conflict in which the weaponization of sound first flowered. The undersea topographical qualities which make the Bahamas a good testing ground in this regard were appreciated in the 1910s as much as the 2010s. Men like Col. Fayban were aware of the military potential of new acoustical technology, but to get accurate understanding of the architecture of the sea floor was not easy. J. E. Williamson had invented a tool which could help solve these warfare problems.

There are always complications though, aren’t there? Submarine Film Corp was bought by a pornography/prostitution-tied conglomerate on the eve of the Navy’s interest in Williamson’s product. At this same time militaries around the world were reevaluating their relationship to organized international prostitution for two reasons: one safe for the public and one secret.

Public: Venereal Disease, while it kept Dr. Wilbert in shoes, was an extremely expensive and entirely preventable drain on fighting forces.

Secret: sex-trade espionage networks had been linked to a devastating spy-ring recently uncovered in Austro-Hungary, home base of the international pimps. This ring had included the Hapsburg counter-espionage chief. As information slowly leaked out of Austria about the particulars of this disaster, the counter-spy’s dealings with prostitutes and his homosexuality were believed to have contributed to the efficiency of this spy-network. Many prostitutes, particularly in Galicia, were apprehended and the Hapsburgs’ relationship with organized prostitution fundamentally changed. Emperor Karl even ended the toleration policies which allowed brothels to flourish around military posts. Military leaders everywhere had to re-think just how close they wanted bordellos to be to their operations. Josephus Daniels and FDR were at the forefront of reorganizing the Navy’s former friends. An example from New Orleans:

The end of the First World War coincided with several significant events affecting the Vieux Carré [a bordello]. One of these concerned prostitution. The brothels and cribs existing within the vivacious Storyville closed after Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels decreed that no prostitution would be permitted within a five-mile radius of naval installations. The unemployed women who operated Storyville, rather than terminate their practices, simply relocated. Some, as W. J. Cash and other historians noted about prostitution throughout the South in the aftermath of the ban, conducted business from hotel rooms with bellboys serving as go-betweens with potential customers. In New Orleans, on the other hand, many ladies of the night preferred to resettle into the French Quarter where rents remained low and sailors and tourists provided a steady and easily accessible cash flow.

Another example would be Daniels’ and FDR’s involvement in the Newport Sex Scandal (1919), where young Navy recruits appear to have been ordered to have sex with men at the Army and Navy YMCA in Newport, RI as part of an entrapment plan to expose a homosexual ring which appealed to Navy personnel. Daniels and FDR never assumed any responsibility for wrong-doing, and were likely motivated by events in Vienna.

As I described in my post on “health films” and the US Navy, where one door closed for well-connected pimps, another opened and soon the Navy was funding a rash of exploitation films. Prostitution had been tolerated previously because it provided a diversion for young men who might otherwise present a political liability. Pornography might provide the same diversion without the risk of unsavory contacts or VD. Pornography could also be useful for recruiting drives… regular readers will not be surprised by Submarine Film Corp’s next cinematic offering: “The Girl of the Sea” (1920).

Moving Picture World, January 17th 1920. Still from “The Girl of the Sea” (1920). This stance was played heavily in advertising displays for the film.

Synopsis: A rich child is orphaned on a deserted island where she grows up to be a “nature girl”, discovered in the bloom of youth by a daring sea adventurer who must save her fortune from predatory…. yada, yada.

Moving Picture World, July 17th, 1920.

Moving Picture World, January 17th 1920.

Moving Picture World, January 17th 1920. A still from “The Girl of the Sea.” Although teen star Betty Hilburn’s character spent the majority of the film in contact with civilization, no one ever though to get her some clothes.

Naturally, the trade press were quick to recognize an angle where the Navy could bear costs for advertising this product:

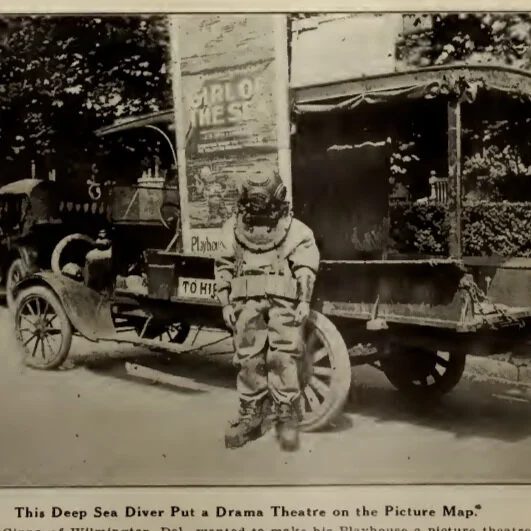

Moving Picture World, July 17th, 1920. This excerpt followed a synopsis of the film and was written to help theater operators market the picture.

And the Navy were only too willing to provide more young recruits:

Moving Picture World, July 17th 1920.

What can we say about Mutual Film’s submarine connection? In many ways it typified the early film industry, particularly the ‘independent’ film industry. When that Monroe-based “third party” chose Leon Goetz to hold the 1910 sub patent, they chose a boy cut from the same cloth as the executives at Mutual. The “third party” had connections to the Teddy Roosevelt administration (like Harry Aitkin’s business partners); they probably knew John R. Freuler; and they didn’t mind working with likely-Galician-Network gangsters like the Shallenbergers.

“The Girl of the Sea” was released the same year as Leon Goetz’s “A Romance of the Movies” starring Edith May, and shortly before Leon was indicted on a violation of the Mann Act, which was designed to combat organized prostitution.