'Health Films' and the US Navy

Historically, criminologists and anti-slavery activists have recognized that two groups of men make up the preponderance of prostitution-consumers: soldiers and other criminals. By ‘other criminals’ I do not mean other prostitutes, but men engaged in illegal activities that are often practiced alongside prostitution: fraud, money laundering, larceny/receiving stolen goods, usury, or human trafficking to name a few. Historically in the USA, voter fraud has been closely linked to prostitution. What I will focus on today is the US military’s attitude toward prostitution, which over the course of WWI deviated markedly from what had been the norm for professional armies through preceding decades. According to National Institute of Health historian Susan Speaker:

“Traditional military culture had accepted drinking, gambling, and visiting brothels as normal, even necessary free-time activities in soldiers’ often rough lives, and nearby communities made money from such businesses.”

For a long time prior to the Great War, developed powers had struggled with the costs associated with venereal disease among soldiers, who often doubled as law-enforcement. Men sick with these illnesses needed long, expensive treatments and ultimately this cost was born by taxpayers wherever the soldiers were posted: a political liability, particularly in colonies. Governments reasoned that if prostitution could be regulated, and the prostitutes given regular check-ups, the spread of VDs could be contained and military effectiveness preserved. This attitude transferred power to those special medical professionals trusted to check the prostitutes (and influence pimps’ income); medical doctors— particularly from Galicia in Austro-Hungary, now Poland and the Ukraine— became leading players in international organized prostitution.

Eventually it became clear that this system wasn’t working. VDs still spread at alarming rates and the fig-leaf of medical supervision of prostitution was exposed. Besides the lack of health benefits, legalized prostitution did not protect men, women and children from abuse. The amount of prostitution swelled as ‘black market’ bordellos sprung up alongside licensed establishments. While pimps undoubtedly got rich, the social costs of toleration were huge. Responsible governments realized that something had to be done to prevent the spread of VDs among soldiers and ultimately the general population. The health of future generations depended upon it.

While in Austro-Hungary the government of Karl I took baby steps to disentangle powerful pimps from its military, the American approach was much more drastic and full of crusading spirit. Prostitutes were confined and quarantined; they were viewed as unwitting agents of the enemy. The culmination of lawmakers’ efforts to limit damage done by VDs was chapter 15 of the 1919 Chamberlain-Kahn Act, which created an “Interdepartmental Social Hygiene Board” (ISHB):

“That there is hereby created a board to be known as the Interdepartmental Social Hygiene Board, to consist of the Secretary of War, the Secretary of the Navy, and the Secretary of the Treasury as ex officio members, and of the Surgeon General of the Army, the Surgeon General of the Navy, and the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service, or of representatives designated by the Secretary of War, the Secretary of the Navy, and the Secretary of the Treasury, respectively. The duties of the board shall be: (1) To recommend rules and regulations for the expenditure of moneys allotted to the States under section five of this chapter; (2) to select the institutions and organizations and fix the allotments to each institution under said section five; (3) to recommend to the Secretary of the Treasury, the Secretary of War, and the Secretary of the Navy such general measures as will promote correlation and efficiency in carrying out the purposes of this chapter by their respective departments; and (4) to direct the expenditure of the sum of $100,000 referred to in the last paragraph of section seven of this chapter.”

While both the Army and the Navy were involved in the ISHB, it was the Navy who 1) was the driving force behind VD policy at this time and 2) had the deepest historical experience dealing with the problem. The $100,000 mentioned in final sentence of the above quotation is important for historians of early film because it represents the birth of the ‘Health Film’ industry. Let’s examine the last paragraph of section seven further:

“SEC. 7. That there is hereby appropriated, out of any money in the Treasury not otherwise appropriated, the sum of $300,000 for the fiscal year ending June thirtieth, nineteen hundred and nineteen, to be apportioned as follows: The sum of $200,000 to defray the expenses of the establishment and maintenance of the Division of Venereal Diseases in the Bureau of the Public Health Service; and the sum of $100,000 to be used under the direction of the Interdepartmental Social Hygiene Board for any purpose for which any of the appropriations made by this chapter are available.”

Education about venereal disease was one of the purposes for this ISHB appropriation. Part of that $100,000— which represented a lot more buying power than it does now— was spent on ‘health films’ to educate soldiers and the general public about the risks of doing business with prostitutes.

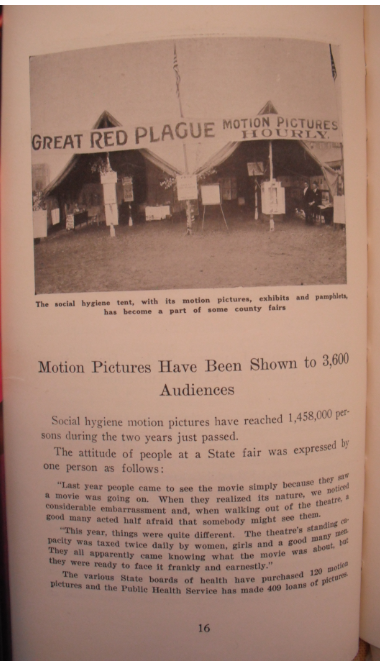

We know that a good number of films on this topic were made. A 1921 publication titled “Two Years Fighting V.D.” or Venereal Disease Bulletin No. 65, states:

“The Various State boards of health have purchased 120 motion pictures and the Public Health Service has made 409 loans of pictures.”

We are told later that 1,458,000 people have seen social hygiene movies since 1919.

From 1921’s “Two Years Fighting VD” issued by the United States Public Health Service.

All of this sounds promising, but unfortunately identifying those 120 films has proven very difficult. One of the titles was “The End of the Road” (1919), which according to the National Film Preservation Foundation, was sponsored by the American Social Hygiene Association; produced by the War Dept. Commission on Training Camp Activities; and directed by Edward H. Griffith. (If he’s any relation to D. W. Griffith is unknown, but in the small world of early cinema, what are the odds?) This is how the film is described:

“Wartime venereal disease prevention film intended primarily for female audiences. Sponsored by a public health organization devoted to eradicating syphilis, The End of the Road tells the parallel stories of two women, one of whom receives instruction in sexual hygiene from her mother, while the other does not.

Note: The End of the Road was originally produced for use by the military. Sometimes referred to as The Story of Life, the popular film was also put in theatrical release but withdrawn in 1919.”

“The End of the Road” was a film that the War Dept. was willing to put its name to, but what about the other 119? Did the US film scene have experience producing engaging, content-rich educational films about socially awkward topics? What sort of film-makers had access to those ISHB honchos throwing about wads of cash, film makers who may have lost income when the military’s tolerated bordellos closed and no longer had need of loss-leaders to get the punters in the mood?

Enter characters such as Albert Dezel. Dezel was the business partner of Howard G. Underwood, who worked with Leon Goetz on 1931 film “Ten Nights in a Bar Room”, which I’ll talk about later. Dezel was a 1920s traveling film projectionist who specialized in military promotion events— somehow he got hold of WWI battle footage, which was not easy to do, and was free to profit from it. Dezel also billed himself as an expert in sexology. Before long, he was in the ‘health film’ market, showing movies which claimed to educate about the dangers of illicit sex and venereal disease.

Here are accounts of some of Dezel’s war work:

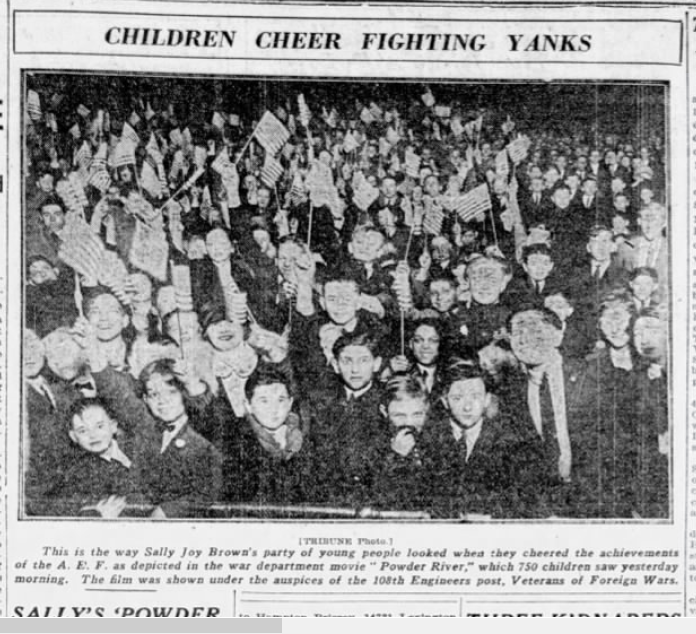

Chicago Tribune, Sunday April 27th, 1924. The accompanying article is below.

Chicago Tribune, Sunday April 27th 1924. Note Albert Dezel and his U-Boat footage, among others.

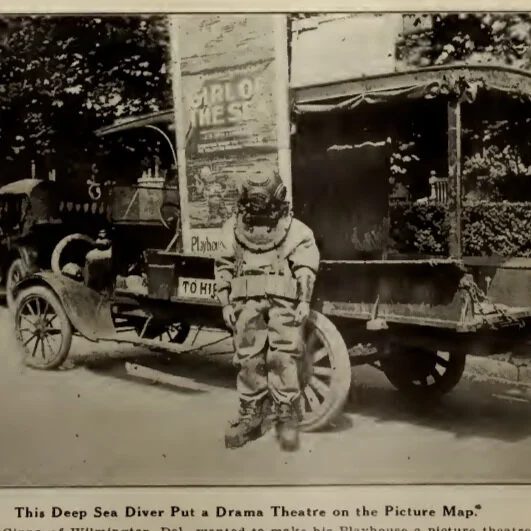

A Dezel war picture advertised in “The Capital Times” of Madison, WI on November 22nd 1924. Dezel had excellent contacts within the military to amass this footage; it wasn’t easy to get.

And here’s some of Dezel’s ‘Health Film’ work:

Medford Mail Tribune (Medford, Oregon) · Wed, Dec 7, 1932 ·Note his film was produced under the auspices of various health departments in the United States and Europe…

St. Joseph Gazette (St. Joseph, Missouri). Thursday, Feb 9, 1933.

It’s unlikely Dezel held any type of doctorate— but who’s gonna check?! It is likely, however, that he had more than a passing acquaintance with organized international prostitution and the ‘White Slave Trade’, which is the subject of the film. Dezel’s hometown, Chicago, was one of the hotbeds of this ugly business and showcased in W. T. Stead’s expose “If Christ Came To Chicago”.

It was in Chicago that men like Albert Dezel and Leon Goetz made their mark in the “Health Film” business; I will explore Leon’s contribution and Dezel’s life in upcoming posts. This journey will take us into the murky realm of Yugoslav spies; international con-men; and personal enemies of J. Edgar Hoover.