Newell Mecartney: A Story for Our Times

I can't think of a better time than now to write about Leon Goetz's business partner Newell Mecartney. In 1931, lawyer Newell Mecartney was listed as one of the incorporators of “US Health Films” alongside Leon in Illinois's “Certified List of Domestic and Foreign Corporations”. After angering Chicago real estate tycoons through anti-corruption activism throughout the 1930s and lobbying against US involvement in WWII, Newel Mecartney was falsely accused of being a Nazi spy by corrupt FBI head J. Edgar Hoover, who sought to use the law as a tool against his political enemies.

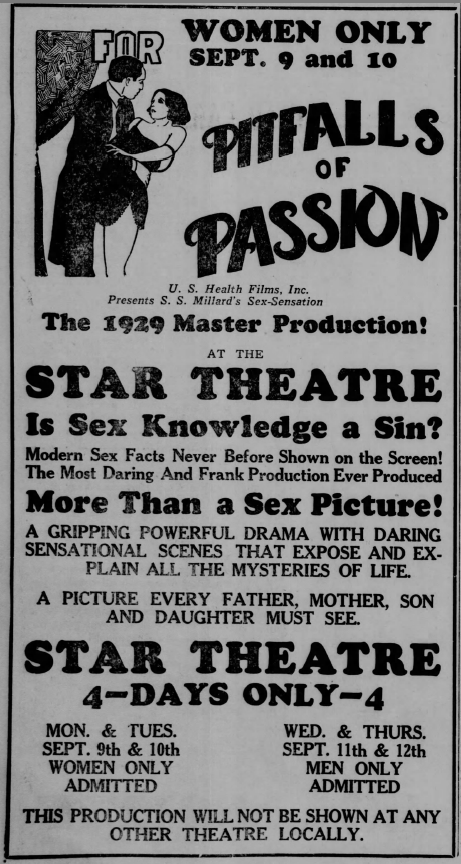

Four years before his 1931 partnership with Mecartney, Leon Goetz had partnered with international con-artist Sint Millard to produce pornographic films under the auspices of “US Health Films Inc.”. The “health film”— pornography— business had been stoked by the US Navy in 1919 in a poorly-administered attempt to “educate” soldiers about venereal disease. While subsidizing porn, Navy leadership (including Franklin Delano Roosevelt) closed the bordellos that had traditionally serviced navy personnel.

Leon claimed Millard robbed the firm of $25,000 (in 1927!) and brought legal proceedings against his partner in Chicago. Millard, who lived mostly in California, was almost certainly engaged in pimping and espionage around the former Yugoslavia. In the face of an illegal immigration charge, Millard was protected from deportation by the governor of California himself at the bequest of a Chicago-based female police agent. These circumstances suggest Millard was an informant on the “White Slave Trade” network, a sydicate of organized crime families from Galicia (Poland) that had had Hapsburg state sponsorship and which doubled as an espionage network. Whether Leon ever got his $25,000 back is not clear, but the sex film the two men made together was still being marketed in 1929.

The Sedalia Democrat (Sedalia, Missouri). Tue, Sep 3, 1929

When Mecartney became Leon's partner, he already had a fascinating history. Mecartney was a lawyer protecting Al Capone's interests in Mayor William Hale “Big Bill” Thompson's 1931 re-election campaign. Thompson, a Republican, had been mayor since 1915 and made no secret of his preference for foreign-policy neutrality and suspicion of the British-- in short, his views reflected those of the majority of Americans.

The 1931 mayoral election in Chicago was bitter. Violence was feared during the election and 70,000 watchers were dispatched to the polls-- such oversight systems are a crucial part of our American democracy. These watchers were on hand to ensure votes were counted fairly and corruption was minimized. Thompson’s rival for the mayor’s office, Judge John H. Lyle, campaigned with a collection of machine-guns intended to be symbols of “Thompsonism”. Thompson, on the other hand, provided Chicagoans with a parade of donkeys, elephants and a camel.

News-Record, of Neenah, Wisconsin. February 23rd, 1931 Part 1/2

News-Record, of Neenah, Wisconsin. February 23rd, 1931 Part 2/2

Readers may be interested to know that Chicago's Medill-McCormick family, Chicago Tribune owners and pre-1918 owners of ‘competing paper’ The Chicago Herald via their lackey James Keeley, were political rivals of Thompson. All these people were nominally republicans. I wrote previously of the McCormick's vilification of Henry Ford's peace efforts (using William Wesley Young’s partner Davis Edward Marshall) and Ford's connection to the cynical Humanitarian Cult. Ruth Hanna McCormick was a particularly bitter foe of Thompson: she was a suffragette and the daughter of Mark Hanna, who sponsored submarine building in the Great Lakes for the British-- and did so against the wishes of the American electorate.

Thompson’s most famous political supporter, Al Capone, enriched himself by “rum running” during Prohibition. NSA-mother Elizebeth Smith noted from her time working for Humanitarian-cult supporter Henry Morgenthau Jr. at the US Treasury that German agents during WWII used the same types of codes that bootleggers employed for smuggling during prohibition. By the 1930s, US politics had taken on the uncomfortable patina of dueling organized crime families.

Thompson did not win the election, but it didn’t go to Lyle either. The winner was Austro-Hungarian immigrant Anton Joseph Cermak (a.k.a. Antonín Josef Čermák) who allegedly played off anti-Irish feelings among Chicago’s immigrant Democrats to win the election. Readers will notice that Cermak’s chances were deemed so slim two months before the election that his name didn’t even make press.

Cermak was shot two years later by Italian immigrant and WWI veteran, Giuseppe Zangara, who was apparently trying to hit president-elect and WWI zealot Franklin Delano Roosevelt while he was shaking hands with Cermak during a Florida rally. The accepted story is that Zangara did this because he hated “capitalists”. Of course, Florida is the state to which Capone fled to when he left Chicago. Florida officials executed Zangara about four weeks after the assassination.

Mecartney was a veteran of WWI himself, and very active in veterans' affairs in Chicago-- which brought him a considerable amount of respect and a large audience. He was a also a real estate lawyer, and his anti-financial corruption activism coupled with his veterans' work would land him in trouble with Chicago crooks who were even better connected than Capone.

Excerpt from The Chicago Tribune, Jan 27th 1933. Mecartney was making real traction dealing with one of Chicago’s more lucrative rackets.

A few months after Mecartney’s activism began to bear fruit and local lawmakers took steps against investment trustee abuses, this happened:

The Chicago Tribune, October 9th 1933.

Newell Mecartney was a fighter and gangland tactics from Chicago’s elite only made him fight harder. In 1936 the US Congress organized a select committee to investigate corrupt “reorganizations” carried out on behalf of real estate bondholders. Mecartney testified before this committee about his work dealing with real estate bondholder “reorganizations” by the Chicago Title & Trust Co (CT&T). CT&T managed a trust that bought bonds on behalf of investors; one year previously Mecartney spoke to the press about how CT&T was “the hub of the bond racket”. Here are biographs of leading CT&T executives, an international band of swindlers, from the 1902 directory “Men of Illinois”:

Mecartney testified to congress that CT&T had been dishonest by not fully disclosing how and when they invested the assets under their trust, with the goal of driving the trust into bankruptcy on paper and then picking up its still-valuable assets cheaply. One particular bondholder trustee, Newton Farr, had borrowed money from the trust and was also a shareholder in CT&T— a boggling conflict of interest.

Marvin A. Farr was Newton Farr’s father. His biography reads: “Marvin A. Farr, Chicago. Born in Essex Co. N. Y. Pres. of the Real Estate Board in 1897; First Vice-President. Union League Club in 1900; in 1901, Governor of the Ill. Soc. of Colonial Wars; Pres. of Kenwood Club two terms and an official of the Midloithian Golf Club; resident of Chgo. since 1872; prominent in civic affairs but never held political office.” Newton would make use of his father’s connections.

The neighboring portrait, of a Hamilton Club financial director named John C. Fetzer, typifies the union between real estate and insurance interests in Chicago high-politics: “John C. Fetzer, Chicago. Born June 13, 1865. Manager of real estate interests of the estate of Cyrus II. McCormick; mem. of the Chicago Real Estate Board; Pres. Ill Northern Ry. (Railway); mem. and Dir. of the Executive Com. of the Protection Mutual Fire Ins. Co.; Dir. Finance Com. Hamilton Club; mem. Grant Park board; Trustee and mem. Finance Com. Chcurch of the Covenant; Sec., Tres. and Dir. “Compania Industrial” of Baja, Cal.; Treas. and Dir. of New National Tunnel & Milling Co. of Colo.”

Mecartney testified about how Newton Farr, and partners W. H. Dillon and Mathias Concannon, bought $300,000 worth of bonds for 25 cents per dollar of their actual worth after the trio had driven the trust which held the assets unjustly into default. Holman D. Pettibone, the president of CT&T, as well as Harrison B. Riley, CT&T chairman of the board, were also involved. The Chicago court-appointed “master” or organizer for the bankruptcy was a friend of Farr's and refused to recognize that there had been wrongdoing, while awarding Farr considerable fees. Mecartney exposed this theft as a “friend of the court” during a case brought on behalf of a mentally incompetent bondholder, John Hoxie.

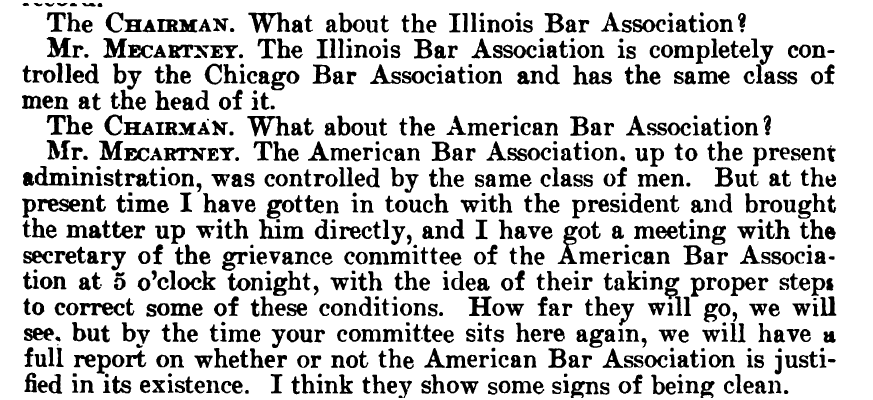

Mecartney's experience with the Hoxie case and his testimony to congress were important for drafting laws creating “conservators” who have the duty to assess bankruptcy cases' assets and protect investors from the type of shenanigans Farr was up to. Mecartney makes it very clear that corrupt judges in Chicago and the Chicago Bar Association enabled Farr:

“Investigation of Real Estate Bondholders' Reorganizations. Public Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Select Committee on Investigation of Real Estate Bondholders' Reorganizations, House of Representatives, Seventy Fourth Congress, Second Season. September 22nd-December 29th 1936. Part 19.

“Investigation of Real Estate Bondholders' Reorganizations. Public Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Select Committee on Investigation of Real Estate Bondholders' Reorganizations, House of Representatives, Seventy Fourth Congress, Second Season. September 22nd-December 29th 1936. Part 19.

“Investigation of Real Estate Bondholders' Reorganizations. Public Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Select Committee on Investigation of Real Estate Bondholders' Reorganizations, House of Representatives, Seventy Fourth Congress, Second Season. September 22nd-December 29th 1936. Part 19.

“Investigation of Real Estate Bondholders' Reorganizations. Public Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Select Committee on Investigation of Real Estate Bondholders' Reorganizations, House of Representatives, Seventy Fourth Congress, Second Season. September 22nd-December 29th 1936. Part 19.

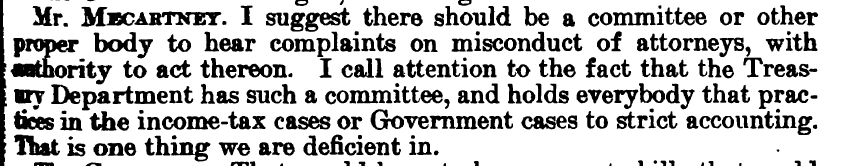

Mecartney provided examples of some of the obscene fees that lawyers garnered from these criminal practices, please see the excerpt at the end of this post for further details. Not content to expose the wrong-doers, Mecartney even suggested to Congress how the situation could be cleaned up:

“Investigation of Real Estate Bondholders' Reorganizations. Public Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Select Committee on Investigation of Real Estate Bondholders' Reorganizations, House of Representatives, Seventy Fourth Congress, Second Season. September 22nd-December 29th 1936. Part 19.

“Investigation of Real Estate Bondholders' Reorganizations. Public Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Select Committee on Investigation of Real Estate Bondholders' Reorganizations, House of Representatives, Seventy Fourth Congress, Second Season. September 22nd-December 29th 1936. Part 19.

Chicago being Chicago, Newton Farr and his criminal friends were never brought to account, in fact they were given greater positions of public trust, according to the Encyclopedia of Chicago:

Realtors, Urban Renewal, and Open Housing

Chicago serves as national headquarters for the National Association of Realtors (NAR), the Institute of Real Estate Management (IREM), and five other real-estate associations. Local brokers were prime movers in the founding of the National Association of Real Estate Exchanges in 1908, renamed the National Association of Real Estate Boards (NAREB) in 1916. ...

NAREB's 1941 report “Housing and Blighted Areas” outlined a plan of federal-aided slum clearance which later inspired the National Housing Acts of 1949 and 1954. Local NAREB and IREM leaders including Holman Pettibone, Ferd Kramer, and Newton Farr helped guide Chicago's early renewal efforts. Pettibone worked hard to promote the “write down” formula which was later incorporated in the Illinois Redevelopment Act of 1947. Kramer, president of the Metropolitan Housing and Planning Council, managed Lake Meadows, a project funded by New York Life, and developed Prairie Shores. Farr, a past president of NAREB, served on the Committee of Six that oversaw the Hyde Park– Kenwood Urban Renewal Project.

The persistence of Farr’s criminal syndicate sheds some light on the history of early film in Chicago. Insurance companies invested heavily in real estate because of the safety of the investment. A reading of “Men of Illinois” shows that many real estate executives were also leading executives in the insurance industry. Harry Aitken, the independent film mogul who partnered with John R. Freuler to found Mutual Film, was Wisconsin agent for Chicago’s Federal Life Insurance Company. Federal Life was started by Hamilton Club founder Isaac Miller Hamilton, a prominent member of the Chicago Bar Association who never did any whistle-blowing.

It was money from Houston Bond, the maitre'd of Isaac Hamilton's club, which paid for the initial stages of the building of the 1931 Goetz Theater.

Isaac Miller Hamilton also started the Hamilton Club, which was a steadfast supporter of Teddy Roosevelt and very forward in its use of film to promote the Republican Party message. See my post on the 1931 Goetz Theater.

Goodridge, the secretary of Chicago’s Real Estate Board, was a member of Hamilton’s club.

This endemic corruption, and the eventual unwillingness of the court system to do anything about it, was very bad news for Mecartney, especially because of his work with veterans. Having fought in WWI, Mecartney had a dim view of the politicians that had sacrificed so many lives for that fratricidal madness. Mecartney used his platform with the American Legion to dissuade Americans against another “world war”. This stance went head-on against the hawkish interests that ran Chicago. To add to the danger, Mecartney planned to run as an independent candidate for a highly-contested judgeship in the sixth district of Illinois. It was time for Chicago’s crime bosses to bring out the big guns.

Chicago Tribune (Chicago, Illinois) · Mon, Oct 27, 1941

Chicago Tribune (Chicago, Illinois) · Wed, Mar 25, 1942

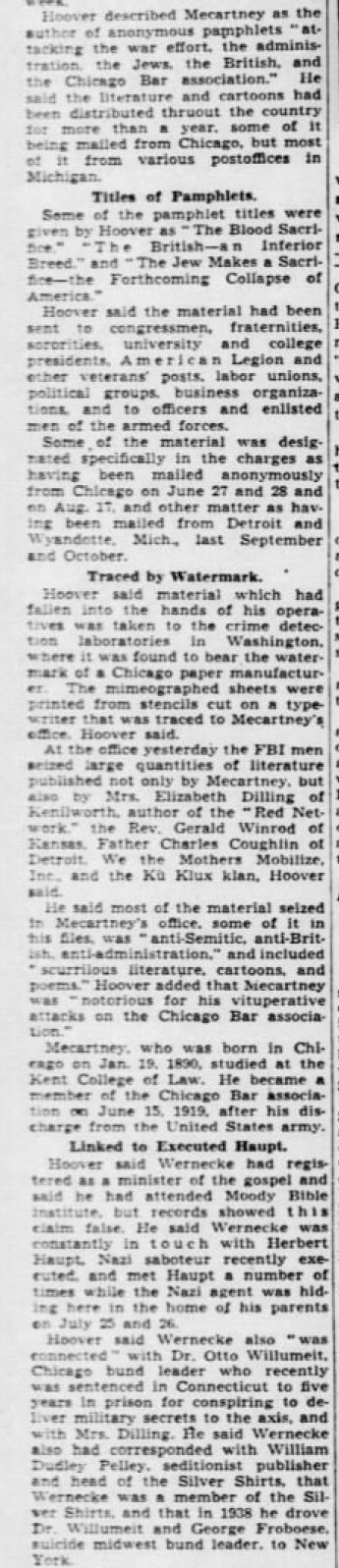

The ‘big guns’ came in the form of eccentric FBI head J. Edgar Hoover, a man desperate to make an example of “pro-Germans and pro-Japs” for his masters in Washington D.C.— who at this time were led by Thompson’s old political opponent Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Hoover, lying to the press and completely without evidence, wove an incredible tale of Mecartney’s maleficence.

Excerpt from “Young Arsenal Displayed after “Minster’s” Arrest”. Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · Mon, Sep 7, 1942

Excerpt from “Hoover Seizes Attorney Here as Seditionist” from Chicago Tribune (Chicago, Illinois). Sun, Sep 6, 1942 1/2

Excerpt from “Hoover Seizes Attorney Here as Seditionist” from Chicago Tribune (Chicago, Illinois). Sun, Sep 6, 1942 2/2

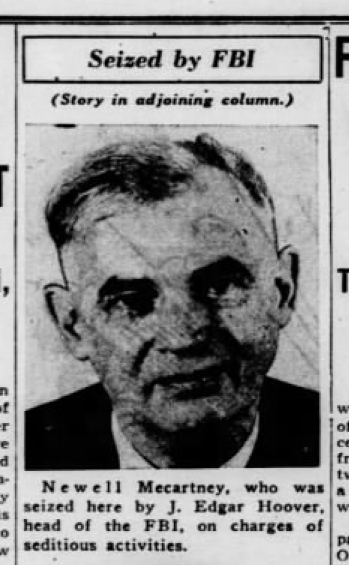

Picture from “Hoover Seizes Attorney Here as Seditionist” from Chicago Tribune (Chicago, Illinois). Sun, Sep 6, 1942

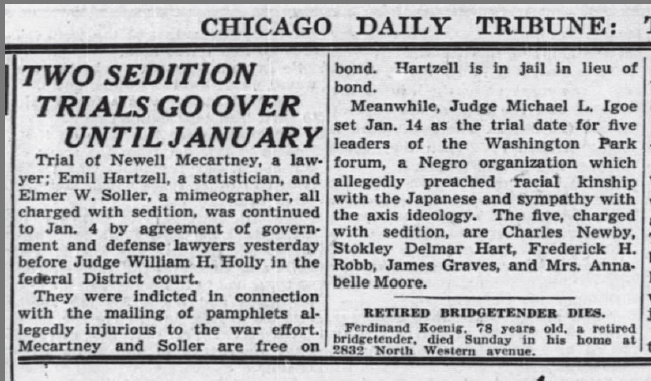

Readers will notice that criticism of the Chicago Bar Association was part of Mecartney’s “seditious” activities, according to the FBI. The article below also describes an interesting group of black activists who were caught up in the same propaganda-manufacturing:

Chicago Tribune (Chicago, Illinois) · Tue, Dec 1, 1942

Of course, the case against Mecartney was eventually dropped due to the FBI's inability to supply evidence supporting the charge. Mecartney in turn sued Hoover and the Illinois Attorney General Francis Biddle, for the return of property they wrongfully removed from his office. Details from the suit expose psychological tactics Hoover used to harass his enemies. Mecartney was in a sense lucky, because it took other German-American defendants two years (in jail) before they could clear their names from Hoover's accusations. Naturally, a Chicago judge refused to hear Mecartney’s case against Hoover claiming lack of jurisdiction.

Our Mountain Home (Talladega, Alabama) · Wed, Sep 6, 1944

What happened to activist Newell Mecartney shows that the abuse of government power for political ends is nothing new, but it is always damaging to our cherished right to free speech. Mecartney was no angel, but his sins pale in comparison to that of the machine he lost a brother, a career, and for a time his freedom, fighting. If we don’t stand up for our rights, we loose them.

——

Below is Newell Mecartney’s testimony before congress regarding his work for Mr. Hoxie, and the outrageous fees that criminal lawyers were receiving in relation to the swindle.

“Investigation of Real Estate Bondholders' Reorganizations. Public Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Select Committee on Investigation of Real Estate Bondholders' Reorganizations, House of Representatives, Seventy Fourth Congress, Second Season. September 22nd-December 29th 1936. Part 19.