William Wesley Young as a British Intelligence Agent

The last time I wrote about William Wesley Young was in reference to Edith May’s day-planner, in which she noted having dinner with a “Mr. Young” twice during the second week of her Ziegfeld Follies experience. I suspect this “Mr. Young” was William Wesley Young, who was well connected in NYC theater and newspaper circles. Ziegfeld counted on those same newspapers to promote his Follies, while his costumer Lady Duff Gordon used a subset of them, the Hearst papers, to exhaustively promote herself.

In this post, I’m going to detail how Will Young, a boy from Monroe, WI, found himself working for British Intelligence in NYC during the run up to the USA’s entry into WWI. I can prove Will’s intel connection beyond reasonable doubt by comparing what Will Young said about his own work to what we already know about British “active measures” against the USA at this time.

From the British perspective, there had to be a lot of secrecy about their “active measures”— attempts at influencing public policy through surreptitious means. These measures were mostly aimed at US elites through literary channels, but WWI saw film used too. The British had to tread lightly though, as President Wilson had been elected on a pacifist ticket. The decision he made to enter WWI in 1917 was highly unpopular. Fortunately for London, some members of Wilson’s cabinet were rabidly pro-British and keen to save the Empire irrespective of the wishes of the American people. A great deal of secret, more justly called seditious, politicking went on in support of this goal, particularly from the office of Wilson’s Secretary of State, Robert Lansing, who set up his own intelligence outfit to this end: The Bureau of Secret Intelligence. Belying the bureau’s goofy name, Lansing worked hard to staff his outfit with informants from across the globe and drew on help from his British connections.

Will Young found his way into British service through these “active measures” campaigns, which were mostly conducted out of New York City with the goal of harnessing US resources in service of policy interests championed by a subset of Londoners, many of whom patronized Lady Duff Gordon. These Londoners found willing help among the Vanderbilt family, the Roosevelt clan and a good many other wealthy East Coast notables, including prominent Quakers like Herbert Hoover, who participated in every aspect of the war effort save active killing. Will’s path to New York started in Madison, WI.

The University of Wisconsin, Madison had no school of journalism prior to Will Young’s enrollment in 1888. Its stands as testimony to Young’s organizational and persuasive ability that he talked the administration into opening a journalism school and letting him graduate with a major in the new discipline. I have not yet uncovered how this new department was funded. While at college, Young also founded the institute’s newspaper, the Daily Cardinal. After graduating he wrote for the Madison Democrat, which propelled him to NYC for the first time.

From 1892-1899 Young worked for Pulitzer-owned papers, starting with New York Morning World (1894-95) then for the New York World on Sunday (1896-99). It was on the Sunday staff that Young made a very important acquaintance for his British work, Davis Edward Marshall, who over the 1897-98 period was employed as Sunday editor for both the New York World and its competitor, Hearst’s New York Journal. Besides being editor, Marshall doubled as a war correspondent for the later, while being European correspondent for the former.

Marshall was both older and more experienced than Young: from 1885-1889 he was news editor for the American Press Association in Buffalo, NY, in 1890 he became Sunday editor of the New York Press and stayed there until 1894, when he became ‘Correspondent on NY Tenement House Reform’ and secretary for the NY State Tenement House Commission. Reforming tenement housing was a priority for NY politician Teddy Roosevelt and his family. These reforms mostly involved low-income properties, typically inhabited by immigrants and very often serving as brothels, a business which at this time was dominated by Austro-Hungarian/Eastern European mafia networks (see Sint Millard), but Italian and French pimps were also represented. Pimp involvement in massive voter fraud was first exposed in these ghettos. Tenement reform was very profitable if you were on the right side of the deal-making.

After “corresponding” on Roosevelt’s tenement reforms for two years, Marshall became “European correspondent” for the Bacheller and Johnson Newspaper Syndicate, which focused on syndicating the work of British writers to American newspapers:

After Hatton [Joseph Hatton, English novelist] returned to England he wrote a series of interviews with John Ruskin, Miss Braddon and other distinguished English writers, and early in 1884 [Irving] Bacheller was successful in selling these to the Boston Herald, the Chicago News, the Washington Post and several other metropolitan papers. Encouraged by his success, Bacheller added other features to his service, which he supplied to newspapers in proof sheets or copy form, and began syndicating a New York letter by Amos Cummings and a Washington letter by W. A. Croffot for weekly publication.

A short time later he took James W. Johnson in as a partner and the operations of the New York Press Syndicate, as they called their enterprise, grew to important proportions in the metropolitan field. Moreover, it expanded into the country field under the terms of an arrangement with the Kellogg Company whereby the latter was able to offer to its patrons the work of the Bacheller-Johnson writers for simultaneous publication with the big city dailies.

By 1892, Bacheller's syndicate was offering to metropolitan papers each week an amount of material equal in volume to one issue of the Century magazine and the features compared favorably in quality with the reading matter in that periodical. They included short stories by such writers as A. Conan Doyle, Rudyard Kipling, Stephen Crane, Stanley Weyman and Mary E. Wilkins, and special articles by such notables as Sir Edwin Arnold and ex-President Benjamin Harrison. During the 15 years that Bacheller's syndicate was in operation he was, as he phrased it, "on the payroll of every great American newspaper except the Baltimore Sun and the Philadelphia Public Ledger."

Will Young met Marshall after Marshall’s Bacheller and Johnson stint; Will had been working for the New York World on Sunday for a year when Marshall was brought on as that paper’s editor in 1897. It was from this Pulitzer-owned platform and through Marshall that Will Young made his first Teddy Roosevelt connections.

If you’ve heard of “Rough Riders”, it’s because Marshall wrote a book in 1899 titled “The Story of the Rough Riders”, published by G.W. Dillingham Co., N.Y.. This book was propaganda extolling Teddy Roosevelt’s exploits during the Spanish-American War; Marshall was present for one day of fighting before being shot in the leg:

The Herald Democrat, April 14th 1899. Part I.. continued below.

The Herald Democrat, April 14th 1899. Part II

Will Young and Edward Marshall formed a friendship, or at least an understanding, that transcended Young’s move back to Chicago and Marshall’s appointment as editor for The McClure Newspaper Syndicate in 1900— where Young would end up working years later in 1913.

The McClure Newspaper Syndicate was a publishing conglomerate closely aligned with British Imperial interests. One of their most famous journalists, Allen Sangree, worked for the New York World at the same time Young and Marshall did; Sangree covered the Boer War and did a character sketch of Cecil Rhodes, who worked alongside Elinor Glyn’s lover Lord Milner during the despoliation. While working for New York World, Sangree’s cover was an official appointment in Cape Town as a secretary to the US Consul-General. Beside Sangree, the McClure syndicate featured writing from Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, and was heavy on British fiction writing, particularly that of G. K. Chesterton, Arthur Conan Doyle, Rudyard Kipling, Robert Louis Stevenson and H. G. Wells.

In 1901 Marshall became Sunday Editor for the New York Herald— but this too would only last a short time. Marshall focused on writing fiction from 1901 until the beginning of WWI conflicts in Europe (1913). While Marshall was reinventing himself, Young returned to Chicago to work for Hearst publications exclusively, including Chicago American (1900-04) and after 1904, when Hearst’s agent John C Eastman bought the Chicago Daily Journal, Young worked for the Journal until 1907. When Young returned to NYC in 1908, it was with a decidedly ‘theater’ feeling, as he had been head-hunted to edit the theater rag Hampton’s Magazine.

By 1908 Marshall had also established contacts in the theater world and earned an income converting popular plays into novels for his “Rough Riders” publisher G.W. Dillingham Co. He hadn’t entirely given up journalistic work though: in 1911 Marshall became the ‘Mexican insurrection correspondent’ for Columbian Magazine, which that same year merged with Hampton's Magazine— where Young worked. Fate had brought both men together again through the employ of Benjamin B. Hampton— a man destined to change the face of early cinema.

Hampton bought the struggling Broadway Magazine in 1908 and renamed it after himself, then hired Will Young out of Chicago specifically to work for him. Hampton was both a film producer and an historian of early film (History of the American Film Industry from Its Beginnings to 1931 is his book); he was also a business ally of John R. Freuler, another Monroe, WI native, and was influential during Freuler’s negotiations with Mary Pickford, which shaped the “star system” we know today. Another of Hampton’s employees at Hampton’s Magazine was Theodore Dreiser, who had been hired by Broadway Magazine owners one year prior to its sale. Broadway was known for its soft-pornography and Dreiser was famous for his sexually-charged fiction. Unfortunately for Dreiser, Hampton was looking for “cleaner” content and he let Drieser go after a short time. Dreiser was close to Sigmund Freud’s representative in NYC, A. A. Brill, an immigrant from Austro-Hungary, whose father had served as non-commissioned officer under Emperor Maximilian in Mexico. (This was the Maximilian who Freud had envious dreams about— dreams where he, Freud, actually became the Archduke Max.) A. A. Brill would serve with William Young a few years later on Educational Film Magazine’s Committee on Pedagogical Research in Visual Education.

Will didn’t stay long with Hampton, who became more involved in the film business and less interested in print. In 1912 Will Young left to be managing editor of the Hearst magazine Good Housekeeping, which would soon employ artist Neysa McMein, National Salesgirls’Beauty Contest judge, to paint cover images:

Neysa’s career took off in 1915, on the back of British attempts to involve the USA in their European war— the painting below, which featured on the cover of Puck was particularly provident for McMein, who would earn a handsome income entertaining troops for the rest of hostilities:

Puck Magazine cover, titled: Misinformation, May 8, 1915.

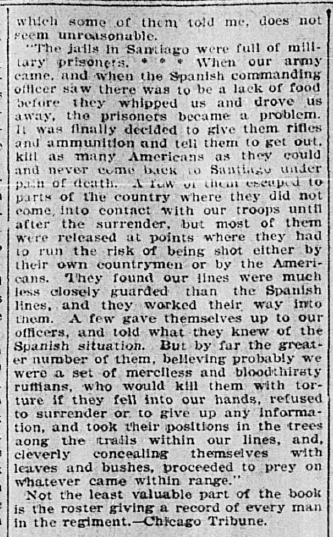

The year following his Good Housekeeping coup (1913), Young became editor of The Publishers' Guide and joined the staff at the McClure Newspaper Syndicate, where Marshall had been hired previously. Young wrote a curious trio of articles which were distributed nationwide by McClure in 1913: “What the Germans are Doing for America”; “What the Jews are Doing for America”; and “What the Irish are doing for America.” These articles detail the power and influence enjoyed by notable individuals from these groups, as well as statistics as to their prevalence in the greater population. While these articles are superficially supportive of the groups mentioned, the underlying message is not positive. During 1913, all three groups were seen by London interests as broadly unsupportive of US involvement in WWI— this would change by 1916.

Buffalo Morning Express, March 30th 1913. Young’s article starts: “The apartment store was the invention of an Americanized German Jew. In an able article on the Jews written several years ago, Herbert N Casson said that, “the Jewish race is like a department store— ask for what you want and it can give it to you.”

Buffalo Morning Express, March 2nd 1913. Iron, of course, is a key defensive resource. Young begins the article by noting the prevalence of people with German ancestry in all states of the Union.

Buffalo Morning Express, March 15th 1913. “What the Irish are Doing for America”, by William Wesley Young. Protestant Americans have traditionally been apprehensive about political influence from Rome.

In 1914 both Young and Marshall would branch out considerably. Young became Sunday editor of the New York Press, which Frank Munsey had bought in 1911 to promote Teddy Roosevelt’s “Bull Moose” campaign. (Marshall had worked there previously in 1890 as Sunday editor.) Marshall, however, started his own syndication concern: “Edward Marshall Newspaper Syndicate Inc.”, which by 1916 purchased “Curtis Brown News Bureau” in London, establishing for itself both an American and European presence. Marshall hired Young for his company in 1918, after Young had worked editing “official British war film”.

How do I know this? Because in 1919 Young and Marshall tried to raise capital for their own movie production company called “Films Incorporated”, and they advertised Young’s war work for the British as film experience which qualified them for the business:

Hartford Courant, November 23rd, 1919. (Hartford, Connecticut. Note: Young claims to have edited almost 1 million feet of British War film! This is the earliest Films Inc. call for money I could find, subsequent ads left out the “British” part of his war-time film work.

Young and Marshall’s claim was advertised various ways during the two men’s quest for investment capital:

The Washington Post, Nov. 30th 1919. Similar advertisements appeared in papers in Pittsburgh, PA and Muncie, IN.

Why would an American be editing British War Film during WWI? We do know something about British “active measures” in the US film industry during this period. According to historian Luke McKernan: “The desire to influence neutral audiences, most particularly the United States, became the object of greatest interest to British propagandists, and it was in this arena that film was first made use of.” Britain’s only known man on the job was an ethnically German American citizen named Charles Urban who ran British efforts to manipulate US audiences against Imperial Germany and her allies:

On 9 February 1916 Urban set sail for America. He had been commissioned by the covert British propaganda outfit, known informally as Wellington House, to organise the exhibition in America of a film Urban himself had produced entitled “Britain Prepared”…. Originally twelve reels in length, the version Urban took with him to America was 7,500 feet, some two hours in running time. Urban also took with him a set of short films produced on behalf of the British Topical Committee for War Films, a representative body of the British film trade which had negotiated with the War Office to enable filming to take place on the Western Front.

Crucially, the Wellington House Cinema Committee failed to secure a satisfactory arrangement for the United States akin to that offered by Gaumont in Russia. Consequently they were compelled to send out someone to make the necessary arrangements on the spot. That representative [Urban] would travel with just a single print of “Britain Prepared”, in contrast to the twenty with which Bromhead [Wellington House’s Russian emissary] had been equipped…

He immediately found a wall of resistance. The film was simply viewed as uncommercial. American audiences had been fed a plethora of topical films at the outset of the war with exaggerated titles— “War is Hell”, “The Battling British”, “European Armies in Action”, “England’s Menace”— that offered only pre-war library footage of troop manoeuvers and parades, and this had aroused a backlash against films claiming to depict the war. Urban asked for permission to re-edit the material to incorporate the best of the ‘British Army in Flanders’ films taken for the War Office, the first of many re-edits of the film material at his command. In this form, and within the tight March deadline set for him by the Cinema Committee…

Urban had reorganized the footage available to him into a series of shorter films, in the hope that in this shorter form they could be more readily booked as part of a double feature programme: “Jellicoe’s Grand Fleet” (four reels from How Britain Prepared), “Munition Making by 300,000 Women of Britain” (another two reels from How Britain Prepared), and the two halves of the film shown at the Strand, “Kitchener’s Great Army” (four reels) and “The Battle of the Somme” (five reels). All were advertised in the film trade press in October under Urban’s name as the ‘official representative of the British War Office’…

Was Young working for Urban? Judging by the amount of footage Young claimed to have access to, there seems to be no other candidate besides Urban who might have been his employer. “Britain Prepared”— the American version— was 7,500 feet and took two hours to show. William Wesley Young claimed to have edited 900,000 feet of British war footage— an enormous amount, which must have been the majority of what someone like Urban had available to work with. In 1916— over a year before the USA entered the war— Urban certainly had call to paste together a wide range of offerings in an attempt to break into the US market, which all together may have totaled to something near a million feet.

This does not make it certain that William Wesley Young joined British intelligence prior to the US declaring war. However, the US only set up a film propaganda division after war was declared in April 1917, and well after Britain had used its stock of war footage to tailor the range of products described above as well as market them to US audiences. It’s unlikely that American war films would have recycled much British footage because movie-goers had a very short attention span for that sort of derivative product. However, when the US did enter the war in April, Urban’s work load increased— his overseers at Wellington House were still concerned about countering anti-war messages in the US media. If Young only worked for the British after April 1917, then the nature of his service is less obvious— he would have been serving a foreign ally intelligence service that had no (known) working partnership with a corresponding US institution.

Is there any way to clarify when Young began working with the British?

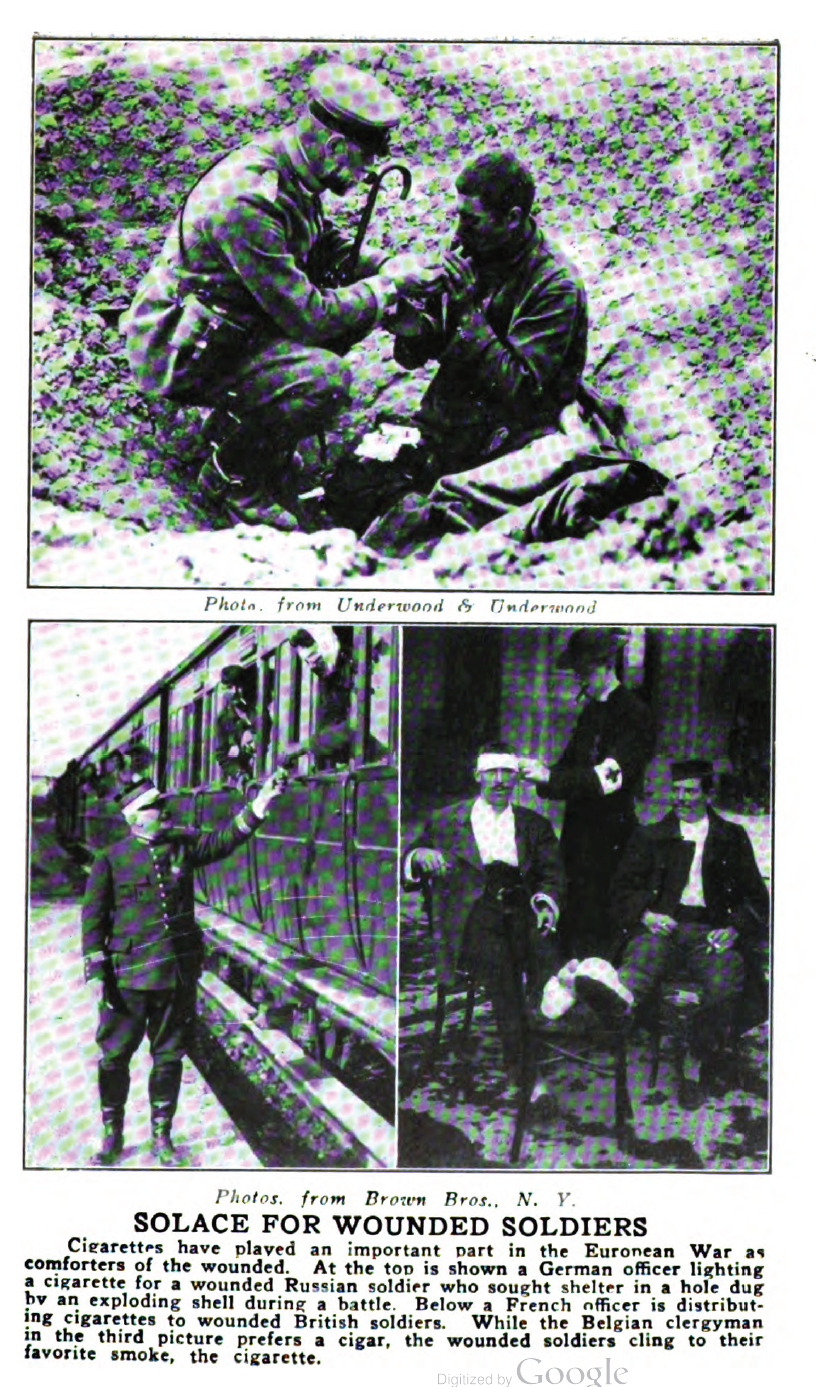

What we can say for certain is that in 1916 William Wesley Young wrote a book called “The Story of the Cigarette” which promoted cigarettes as a beneficial distraction for men fighting on all European fronts. This was a clever move, as the cigarette drive could not easily be be dismissed as British propaganda alone. The British “preparedness” message was based on the same psychology, in that London didn’t want to push for war directly, but instead to promote a ‘wise course’ of being well defended should war come— a much more palatable message for American people inclined to pacifism. Consequently, drives to supply cigarettes to European soldiers were well underway in the USA— particularly via the theater business— one year prior to US involvement in WWI. Of course, once war was declared, American politicians like Teddy Roosevelt became very open about their support for the cigarette drives, exposing the true ideological motive behind this British propaganda. William Wesley Young’s 1916 seeds had been well planted.

Image from William Wesley Young’s “The Story of the Cigarette” published in 1916 by D. Appleton.

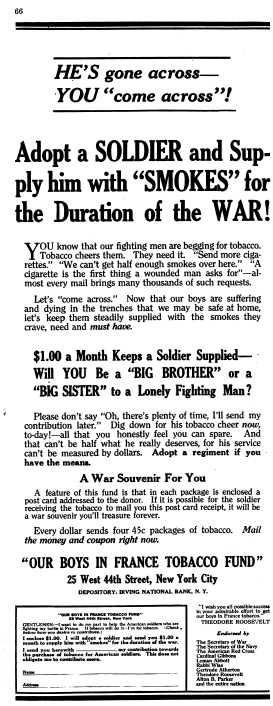

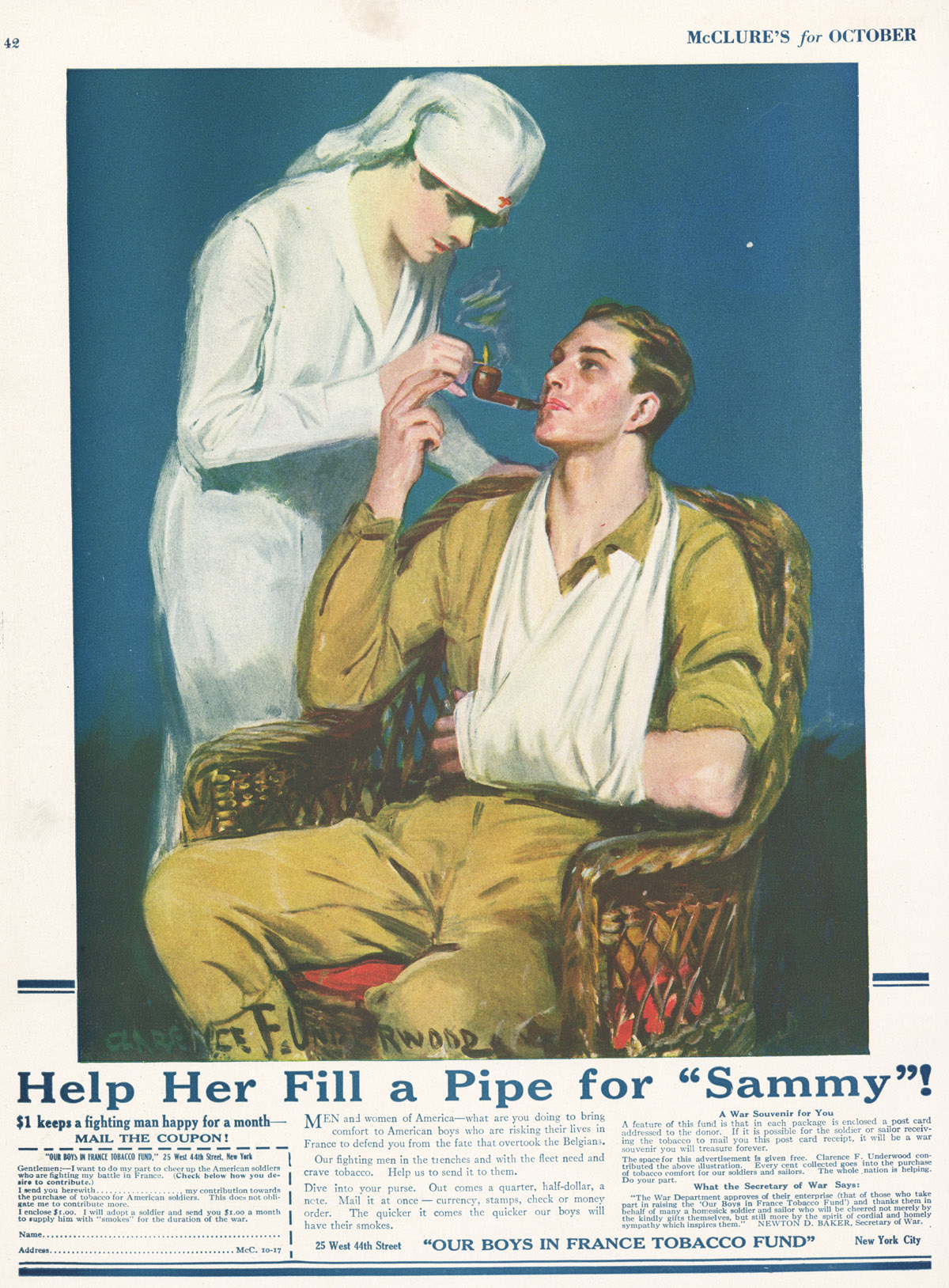

The following are images from cigarette drive campaigns from after US entry into WWI.:

Advertisement from McClure’s magazine, January 1918. Note the Teddy Roosevelt quote, bottom RHS.

Image from McClure’s magazine, October 1917. Courtesy of Stanford Research Into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising (SRITA), which states: “This ad encourages Americans to donate funds to the Our Boys in France Tobacco Fund, one of many tobacco funds for World War I soldiers. In 1917, the New York Times listed the Our Boys in France Tobacco Fund alongside the Belgian Soldier s Tobacco Fund and the Evening Sun Tobacco Fund as war charities with satisfactory accounts. By the next year, an article in the New York Times quoted a woman in charge of An Army Girls Transport Tobacco Fund as saying that there are hundreds of patriotic American societies, clubs, and individuals who are raising funds for smoke comforts of our soldiers. Clearly, funds like this were common, speaking to the widespread prevalence and apparent acceptance of smoking. This particular ad portrays smoking as a healing tool, as the injured soldier, unable to use his broken arm, looks up with appreciation at the nurse lighting his pipe.” (Accessed December 2019.)

Mary Pickford, the most valuable of the pre-WWI movie stars, was active promoting cigarette smoking among American servicemen. The Wisconsin Historical Society provides a publicity picture of her handing out boxes of cigarettes with the caption: “Mary Pickford getting tobacco and cigarettes for the soldiers. In addition to supplying her own adopted contingents, Miss Pickford has sent thousands of smokes to the boys in the trenches. The others in the picture are Norman Kerry, in uniform; Marshall Neilan, her director and Theodore Roberts."

Given William Wesley Young’s long-standing connection with Anglophile publishing concerns; his fishy 1913 articles targeting groups that the British distrusted; his employ by men involved intimately with Mary Pickford’s film career; his authorship of “The Story of the Cigarette” in 1916; and his self-professed work with “official British war film”, I think the only reasonable conclusion is that Young was an agent for British Intelligence from at least 1916, and possibly earlier. This fact will provide insights to his (and Marshall’s) propaganda activities around pacifist Henry Ford, which I will examine in a following post.