Lady Duff Gordon

Lucy, Lady Duff Gordon. Courtesy of Columbia University’s Women Film Pioneers project.

In September 1920, when Edith May Leuenberger traveled to NYC to take part in the Ziegfeld Follies, a prize job-offer she’d won through the National Salesgirls Beauty Contest, she was chaperoned by journalist Zoe Beckley. Beckley, a some-time feminist and regular column writer for the Newspaper Enterprise Association which sponsored the contest, described Edith May’s experience to Monroe, WI area readers in this way:

(Monroe Times, September 28th 1920.)

“EDITH TELLS OF BIG CITY; Girl in Letter Speaks of Meeting the Famous Artists of New York

Clothes by Lady Duff Gordon, famous Fifth avenue modiste, and a suite of rooms at the Waldorf Astoria, is “some class”, little Edith May Leuenberger, who is soon to be a movie queen, thinks.”

Beckley was being honest in featuring the work of Lady Duff Gordon (henceforth LDG) as part of the glamor Edith May was supposed to enjoy. (If Edith May stayed in the Waldorf Astoria at all, it was only for a day or two at most. For the majority of the time she was boarded at the McAlpin Hotel, a much more mundane affair famous for trysts among that set of gentlemen who would pay for showgirls or rural teenage boys.)

While the Waldorf was smoke-and-mirrors, LDG really did costume the girls who worked for Flo Ziegfeld. This arrangement between the “modiste” and the “connoisseur of beauty” is one of the most interesting in the Goetz story because of LDG’s connections to the highest levels of Britain’s power elite. Between LDG and her romance-author sister Elinor Glyn, there existed a network of lovers, friends and financiers which included Lord [George Nathaniel] Curzon, Lord Milner, Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon, Sir Alexander Condie Stephen (representative of Edward VII), Grand Duchess Kiril of Russia, Herbert and Margot Asquith and the Vanderbilts, an American family who were particularly helpful establishing British Intelligence’s presence in the US film industry.

LDG’s sister Elinor Glyn, portrait courtesy of the UK National Portrait Gallery. Glyn made a name for herself writing “Three Weeks”, a sex-heavy romance with a ‘cougar’ heroine.

The sisters worked as a team: LDG would advertise Elinor Glyn and vice versa. Their most famous creation was Clara Bow of “It Girl” fame. “It” is sometimes described as sex appeal, but I think “It” is more of a combination of sex appeal and extreme narcissism. Below is a clip of Glyn describing what “It” is, using the same metaphors that Sigmund Freud used to describe his conception of narcissism in the famous 1914 essay “An Introduction to Narcissism”, i.e. the ‘big cat’ attitude.

LDG and Elinor Glyn were “influencers” to use a modern term, and they were effective “soft power” tools pushing the social and political agenda of a set of moneyed people— mostly based in London— whose values and politics were at odds to the preponderance of Britain’s aristocratic elite. Glyn was romantically involved with many men, but particularly attached to Lord Milner, famous for his South African concentration camps and delivering natural resources into the hands of families like the Oppenheimers and Rothschilds. Another of her long-time lovers was Lord Curzon, known for his “Great Game” stratagems at a time when Britain, Imperial Russia and Austro-Hungary were competing for control of Persia.

Although LDG and Glyn were well connected, they did not represent the national interest, and Glyn in particular found herself disliked by legitimate diplomats. LDG and Elinor Glyn were so effective at thumbing their nose at Imperial Russia that they caused trouble for the Foreign Office, which ended up banning “Three Weeks”, a cougar-themed play by Glyn, for fear of diplomatic fallout— but more on that in a moment.

To really understand these two women, a look at their friends is useful. To that end, here are a few quotes from LDG/Elinor Glyn biography “The IT Girls” by Meredith Etherington-Smith and Jeremy Pilcher:

“… she [LDG] was much happier in the company of women, or of unthreatening boys who were much younger than she was and often homosexuals.. This friendship with a powerful woman [the bohemian Ellen Terry] would repeat itself over and over again during the course of Lucy’s [LDG’s] life. Her most intimate friends were women like herself— financially independent through their own efforts, surrounded by a circle of dominated men and younger women who played to roles of acolytes.”

One could say that LDG’s outlook on human relationships was “Socratic” along the lines of Plato’s understanding as presented in The Symposium. Elinor’s character was less practical. While no means aristocratic, Elinor (and the rest of her family) longed for the elegance and acceptance of such society:

“Elinor developed into a quiet child, totally out of touch with the real world, living in an imaginative territory peopled by aristocratic shadows… Elinor never reconciled the aristocratic ideals of her grandmother with contemporary reality. When she tried to write about poverty or the lower classes, she made a poor job of it.”

Both girls lived fantasy-lives which lead to a facility for lying: “Elinor and Lucy were both expert at manufacturing convenient myths to conceal the rather more inconvenient truth. The trouble with this mythologizing was that both sisters ended up believing it.”

This fevered romanticism was not extended to financial matters, however. Both Elinor and LDG were chronically short on money and made marriages of convenience. The consequent divorce/torrid affairs shut them out of polite society, leaving the “haute bohemia” of Cafe Society as their only option— society which LDG’s daughter described as “ those awful people”. Oscar Wilde numbered among them:

“Lucy had started designing at a perfect time. Rigid Victorian society was beginning to relax both its rules for entry and its behavior. The old landed aristocracy was in the process of losing its power, and “new money” was being let in, encouraged by the Prince of Wales. Rich Americans were coming to London to marry off their Dollar Princess daughters to Titles.”

Whatever they thought privately, LDG and Glyn found their métier among these libertine artists and nouveau riche, who together composed the ‘upper half’ of LDG’s clients and the consumers of Glyn’s cougar stories. The lower half of LDG’s clientèle were show people or pricey prostitutes. To appeal to all these groups, a significant capital outlay was necessary to establish the requisite prestige. Who would bet on these impractical sisters?

LDG’s clothes business was financed by Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon and a shadowy “Mr. Miles” from the accounting firm “Jocelyn, Miles & Blow”. Sir Cosmo was rich from the British East India Company** and came from a literary family close to the John Murray publishing dynasty. Sir Cosmo married his “modiste” investment when there was risk that LDG might fall into the orbit of another mysterious suitor, the anonymous “Lord L”. The LDG/Sir Cosmo marriage was not a close one.

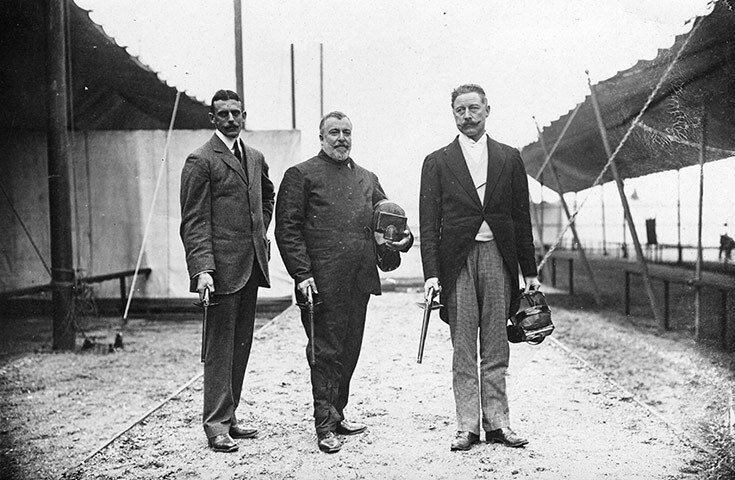

“Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon (right) poses with W. Bean and Captain MacDonnell, all three holding duelling pistols and protective masks.” Courtesy of JeremyBlevins.com

Elinor’s marriage— like both of LDG’s— was a non-starter and she was famous for her affairs: “It is a tribute to Elinor’s personality and her energy of mind that she was admired by two of the most important statesmen of her age.” These statesmen were Lord Milner and Lord Curzon; Milner put Curzon in Elinor’s way through the pair’s voluminous correspondence:

“Their correspondence and occasional meetings continued regularly until 1907; then there is a gap of three years, three of the most important years in Elinor’s life. The letters and meetings were resumed briefly in 1910, lapsed again, then resumed on a regular basis until the final letter from Milner, in 1921. The timing of this correspondence with Milner is extremely interesting, for it ceases when Elinor began to get involved with Curzon, the great love of her life. It resumed when Curzon dismissed Elinor for the first time, ceases when there was a reconciliation, and then continues after the traumatic finality of Curzon’s second marriage.”

1907 was a watershed year for the sisters— and also the year their client Margot Asquith’s husband Herbert began staffing what would become MI-6. Asquith’s new intelligence organization was designed to target his political enemies who saw economic rapprochement with Imperial Germany as Britain’s best strategy. Grand British merchants— many (if not most) of whom were descended from German-speaking immigrants in London— had lost their edge in international trade and Germany was their main economic competitor.

For Elinor, 1907 saw the birth of her book “Three Weeks”, which was also the death of her aristocratic pretensions. Elinor quickly developed a stage version of the book at the behest of her friend Grand Duchess Kiril of Russia; Glyn cast herself in the lead role and, naturally, LDG supplied the costumes. Society balked at its passionate depiction of a sexual fling between an aging woman and young man, which true to contemporary pornographic practice, ended on a moralistic note stressing the negative consequences of illicit sex. Bohemians loved the work, but the rest of the world saw Elinor as a rather gross “Scarlet Woman”.

Lord Curzon supported the play-version of “Three Weeks”, which was effectively banned by the Foreign Office “for the possible reason of not upsetting Russia— an important ally.” Etherington-Smith and Pilcher note that there was speculation that “someone at the Russian court might have thought that she [Glyn] knew more than was good for her about the Czarina, and that Three Weeks might have touched on something near the truth.”

A 1910 promotional postcard for “Three Weeks” as a theatrical play; by this time Elinor Glyn had been replaced by a professional actress. Courtesy hippostcard.com.

Was Elinor Glyn’s behavior towards the Tsar that of an agent provocateur? Certainly, on a visit to Russia in 1910 Glyn showed “knowledge of some not generally-known details about the Winter Palace, which she explained away by the astonishing claim that she was the re-incarnation of Catherine the Great.” British intelligence had for decades targeted important Russians using occult circles, as is described in Richard Spence’s biography of Aleister Crowley, “Secret Agent 666”. Whatever Elinor was doing in Russia, it got her briefly kidnapped (in the most genteel way) and she had to be rescued by the British Foreign Office.

Exiled from polite Anglo society, the sisters sought money and fame from the lower half of their clientele: theatrical personalities. In 1907 LDG scored a coup dressing Lily Elsie for her role in “The Merry Widow”— which made the unknown actress a star and fashion icon overnight. Lily Elsie was a fin de siècle sex symbol who was very good at getting rich men to give her expensive presents while not sleeping with them, as she claimed. LDG’s fame among Lily Elsie fans propelled her into something akin to “mass market” appeal.

The beautiful Lily Elsie, dressed in the famous LDG “Merry Widow” hat and dress. Image courtesy of gogmsite.com.

Also in 1907, Elinor Glyn toured the USA on the back of the release of “Three Weeks”. In the USA, a functionary of Edward VII made sure Glyn met Teddy Roosevelt— a regular on this website— as well as notables like the Vanderblits and an underwhelmed Mark Twain. Two years later, in 1909, LDG made the same pilgrimage, this time backed by the theater agent daughter of J. P. Morgan (Bessie) and the wife of a Vanderbilt (Elsie): “Elsie persuaded Lucy that the ladies of New York were ripe, as it were, for the sartorial plucking…”

Exploiting press and theater contacts, the Bessie/Elsie duo helped establish LDG— her name was so ubiquitous that some pressmen started to call her “Lady Muff Boredom”. Part of this press assult involved the living models LDG ‘invented’ to give backstories to her dresses: “Lucy took four of her best mannequins with her— Gamela, Corisande, Florence and Phyllis. The American press went overboard for these statuesque beauties.” These “mannequins”, along with Mauresette who I wrote about previously, inspired Flo Ziegfeld to invest in a higher-class image for his showgirls.

“Leaders of Society, such as Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish and Mrs. Vanderbilt, took this extravagant bait. Far from being put off by Lucy’s insulting missionary attitude, they were agog to view these extraordinary mannequins… Lucy delicately advertised some of her models as ‘Money Dresses’. [LDG speaks] “Though I have always set my face against ostentation, I called them “Money Dresses” because it takes so much to buy them,” she explained in her advertisements, lest Americans failed to understand what she was trying to tell them.”

Why was this faux aristocrat so popular in a break-away British colony? “The social stranglehold of the old patroon families, with names like Stuyvesant and van Rensselaer, had been giving way to a new society of incredible wealth obtained in railroad and property development, mining and steel.”

I will break off here, at the verge of LDG/Elinor Glyn’s NYC stage and Hollywood careers, which I will cover in upcoming posts. What I hope to convey to readers over the course of this blog is that the Ziegfeld phenomenon which Edith May was a part of, and that Leon Goetz exploited, was indicative of a cultural shift that had everything to do with the declining economic position of powerful London merchant families and their New York City satellites. LDG’s British intelligence contacts will also provide some explanation for Edith May’s 1920 visit to Quaker proponents of 1950s/60s era non-violent political action during her Ziegfeld stay and William Wesley Young’s involvement with the Ziegfeld/Salesgirl Beauty contest scheme.

** The Duff-Gordons had shadowy connections to the BEIC. The head of the company’s intelligence apparatus was LDG’s great aunt Lucie Duff Gordon’s childhood friend, John Stuart Mill. Later in her married life, Lucie and her husband took an extraordinary political risk “handling” a person of interest to J. S. Mill named “Azimullah Khan”. Azimullah would play a particularly bloody role in the 1857 Mutiny, after which Mill fell from political favor. Lucie and her radical friends provided Azimullah with political coaching. That the Duff Gordons would take such a risk without considerable financial remuneration from Mill and the Company is unlikely. The Duff Gordons never talked about BEIC investments or connections, for reasons I think are obvious, and instead acknowledged their sherry business.