Duff Gordon Sherry

I owe today’s post to ViennaArtPlates.com and their fantastic images of a Duff Gordon Sherry advertising plate from 1906. The Duff Gordon firm relates to Goetz movie history through Lucy Duff Gordon, “LDG”, who was costumer to the Ziegfeld Follies for about a decade up through 1920. Wearing LDG creations was one of the “perks” Edith May Leuenberger, the daughter of a Monroe, WI blacksmith, enjoyed after winning the National Salesgirls Beauty Contest and becoming one of Ziegfeld’s employees.

It is important that LDG’s investment capital came from sherry, because the export of Iberian fortified wines played a key role in Britain’s empire, as well as in illicit slaving networks which were known as the “White Slave Trade” in the 19th and 20th centuries. The “White Slave Trade”, the dominant organized international prostitution network, was controlled by crime families from Austria-Hungary’s Galician territory and was supported by the Hapsburgs. This trade spanned the globe and had existed for centuries prior to Galician control— indeed the history of Mediterranean trade is the history of slave-exports out of Europe.

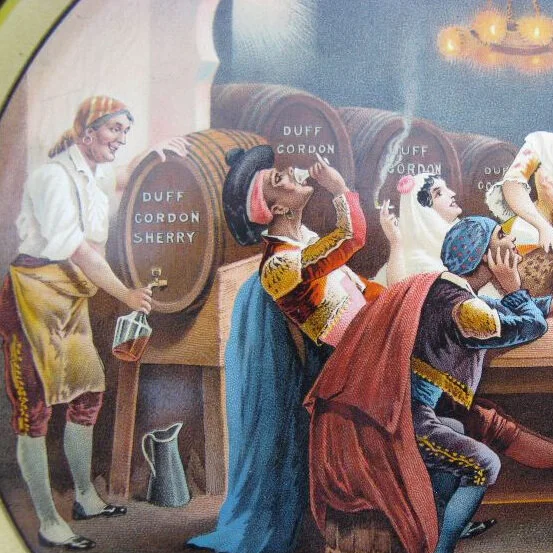

A “Vienna Art Plate” advertizing the Duff Gordon family sherry export business. The plate dates from 1906 and was made in Coshocton, Ohio, USA. A thriving advertising industry existed in this town prior to the industry being centralized in New York City after WWII. The “Vienna” name has nothing to do with Austria-Hungary, the company was simply trying to capitalize on the city’s reputation for art-goods. Courtesy TinViennaArtPlates.com.

Image of the back of the plate pictured above. The inscriptions flanking the crest read:

“Duff Gordon Sherry has been furnished the Medical Department of the United States Army and the Marine Hospitals of the United States Navy for over 20 Years.

His Majesty the King granted Mess Duff Gordon & Co. the privilege of branding their wines with the Royal Arms of Spain.”

LDG’s lingerie capital came from her second husband, the fortune of Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon. British merchants played an outsized role bringing Portuguese and Spanish fortified wines to the rest of the world in the 19th century because the British had triumphed in an economic war they’d fought with Catholic Spain since the time of Elizabeth I. The British were able to get this economic power, at least in part, by partnering with interloping traders to undermine Spanish control of the economies of their South American colonies.

Historians don’t know much about these interloping traders; many worked out of Jamaica and Amsterdam. It appears that a good number were “conversos”, that is Spanish Jews who converted to Christianity for political reasons and who were willing to use their positions inside Imperial Spain’s trade and colonial government institutions to undermine the Spanish crown.

We know even less about the way goods moved through this interloping Atlantic trade, except that the cost of this trade was crippling to Spain and that most Africa-sourced slaves were brought to the New World via illegal trading networks (estimates are as high as 75% of Black slaves arrived this way in British-controlled territories like Jamaica). Ironically, despite copious writing on the Atlantic Slave Trade, we know little about it because of the lack of research into interloping traders.

What we do know is that by partnering with these “pirate” networks, the British found one way to undermine their Spanish competitors, who started with a far more developed empire and navy than QE1. Oliver Cromwell was particularly keen to develop ties with Jamaican networks; reach out to Jewish partners; and build his “New Israel” through the famous 1654 “Western Design”.

Pirates like Inquisition-refugee Rabbi Samuel Pallache not only dealt in European slaves— one of Europe’s largest exports until about 800 A.D.— but contraband goods from Spain’s South American Colonies. While this trade in European slaves never stopped, it had been suppressed by European rulers from Charlemagne down until the ascent of the Medici. The Medici, the banker princes who Aby Warburg idolized, decided to develop Leghorn/Livorno as an “Algiers of Christendom”, where slave traders, including men like the Amsterdam-based Rabbi Pallache, could conduct their trade unmolested. Concomitant to Leghorn’s international trade and diversity was a re-flowering of enslavement in Europe.

Cromwell’s policies not only entangled Britain with the more modern Atlantic slave-trade, but also with its mother, the Mediterranean Slave Trade— a far older and ongoing business where Europeans went into the Middle East and medicines (spices) came out. The Atlantic trade complicated already-existing Mediterranean trade networks, which grew from coast-hopping Venetian vessels destined for the Balkans and other Ottoman lands. (Both Christian and Muslim sources identify Jewish merchants as leaders in this network.) Venetian dominance gave way to British and for a long time Britain provided the ships which moved all of these things and people about. By the late 1800s Austria-Hungary had made serious inroads into the Balkan end of Mediterraenan trade and Imperial Germany surpassed Britain in shipping everywhere else. The Atlantic Slave trade had been crushed, but the Mediterranean trade remained strong, and was now called “the White Slave Trade”.

One of the consequences of Cromwell’s “Western Design”/Jamaica policy was that native Brits were squeezed out of control of the chartered companies QE1 created as engines of empire, like the Muscovy, Eastland (Scandinavia) and Old East India Company. Rich Iberian wine traders who had lost investment opportunities because of the Nine Years' War (1688-1697) were a leading faction among the “unorthodox investors” who exploited political favors to displace the native British merchants in London: one example of which was the creation of the “New East India Company” in 1694. (Readers should not be under the misapprehension that this displacement was done through better “business savvy”, seamanship nor other meritocratic reasons. Corruption and influence-peddling were the order of the day.) “Unorthodox investors” not only encompassed disaffected Scottish traders, but also Dutch merchants, radical protestants like Huguenots and Quakers, and Jews. By 1800 at the latest it was “unorthodox investors” lead by immigrant German-speaking merchants from the Holy Roman Empire who controlled the ‘British’ Empire.

The British Government allowed this because it used these diverse “unorthodox investors” for provokatsiya espionage operations against its military and economic competitors. The interloping (pirate) network between London-Oporto-Lisbon was particularly helpful for these undertakings; many of these ‘Iberian’ traders were actually German-speaking and subjects of the Holy Roman Emperor (again!)— or at least their families were until recently. Not even the British Navy were able to check the operations of these interlopers, who worked both with and against their British partners, as their private interests dictated.

Iberian Wine Merchant Network Hub: The Douro Port-producing region in Portugal, note how the wine could be shipped via the Douro River to the Atlantic port of Oporto, which was also important for South American trade from Spain’s colonies.

Contrary to popular belief, Great Britain became wealthy by bringing colonial goods to already-developed European markets like Spain and Central Europe, not by trading between her colonies. The tricky thing was that these markets had strong trade controls which made black market trading very lucrative— if you could get the right smuggling partners. London’s “unorthodox investors” excelled in this smuggling: the same networks which could move people illegally could move contraband goods, banned literature, pornography etc.

‘British’ economic power in Portugal meant they could dictate trade terms in their own interests, as historian Kenneth Maxwell explains:

The English factory in Oporto had initiated the wine trade in 1678 as a substitute for the re-export trade in Brazilian sugar and tobacco the Portuguese had lost to the competition of the West Indian islands which, under the Navigation Acts, received privileged access to the English markets.

Soon the port business became a symbol of foreign exploitation among indigenous Portuguese:

At the heart of the port trade is a changing but continual struggle between Portuguese family farmers who raise port grapes and merchant exporters, many, but not all of them, British, who export the wine and have relatively recently come to dominate its production as well.

Consequently, when the Marquis de Pombal, a creature of Maria Theresa, came to power in 1750 renegotiating British port-trading privileges and creating a state-controlled port-production monopoly became central to his cameralist plans— as well as those of his sponsor the Hapsburg Empress, who was extremely jealous of British economic success. Via foreigner-friendly trading privileges and creating state monopolies for cronies, Pombal hoped to attract pirates like Pallache to Portugal and beat the British at their own game; Maria Theresa hoped to do the same in Trieste, her version of the Medici’s Livorno, where she issued blanket pardons to all criminals wanted elsewhere who could assist her international trading. Trieste’s fate as a nexus of human-trafficking and related crime was sealed. Similar problems were instituted in South American metropolises at this time.

Useful ports for Slaving and Contraband: Coastal European cities played an important role moving slaves captured by Moorish, Jewish and Ottoman pirates (sometimes a combination of the three!) as well as contraband goods from Portugal’s and Spain’s empires in the New World.

The Duff-Gordon family, of Scottish extraction and therefore an “unorthodox investor” in the London scene, was one of a handful British subjects who benefited from a similarly poisonous economic situation in Spain:

The sale of Sherry in the Indies was frequently hampered by pirates who seized the fleet's cargo and sold it in London. The greatest haul of sherry wine was made in 1587 when Sir Francis Drake attacked Cádiz and carried off 3,000 kegs of sherry. When this booty arrived in London it made sherry fashionable in the English Court and Elizabeth I even went as far as to recommend it to the Count of Essex as the best of wines. As a consequence of this rapid increase in the consumption of sherry and a limited supply, King James I decided to set an example to his subjects by ordering that the Royal Cellars should limit the amount of sherry brought to his table to a modest 12 gallons (48 litres) per day!

The demand for Sherry rose steeply and the English decided to obtain our wines by fair means or foul. In 1625 Lord Wimbledon attempted another attack on Cádiz, this time unsuccessful. It was probably this failure which led the English, Scots and Irish to guarantee their supplies of sherry through the usual trading channels by establishing their own businesses in the Region.

The 17th and 18th Centuries saw the arrival of wine merchants such as Fitz-Gerald, O'Neal, Gordon, Garvey or Mackenzie. Later they were followed by Wisdom, Warter, Williams, Humbert or Sandeman. Being British subjects some Jerez wine-growers were able to bring pressure to bear on the British government to lower excise duties, achieving their objective in 1825 with a reduction of two duros (a Spanish coin of the time) per butt. This led to a four-fold increase in sales of sherry between 1825 and 1840.

Apart for the sherry-money, we also know from Lucie Duff Gordon (LDG’s great-aunt) and her connections with John Stuart Mill and Azimullah Khan that the Duff Gordons were intimately bound with the New British East India Company by the 1850s— the “unorthodox investor” incarnation of that chartered company. This is a very predictable synergy given the economic realities of the fortified wine business.

So why was this seedy sherry money chasing Lucy Duff Gordon’s lingerie?

LDG was an aspiring socialite when she married a more socially-connected port merchant named James Stuart Wallace. Unfortunately, her husband was a low-functioning alcoholic and Lucy was soon divorced with no way to support herself. She began to take gigs sewing personalized dresses for her sister, Elinor Glyn, and Glyn’s wealthy friends.

Glyn had married into a family which had done very well during Austria-Hungary’s “Gründerzeit”, the first wave of industrialization under Franz Joseph I, husband of Sisi and grandfather of Rainer. The Glyn bank was named “The Anglo-Austrian Bank”. During the early years of this bank (1848 until the stock market crash of 1873) the economic resources of Austria-Hungary were opened up to tractable 1848 revolutionaries/’Liberal Party’ power-brokers and their foreign allies in a particularly irresponsible way. The Glyn Bank profited from this irresponsibility and had divested itself of speculative investments by the time of the 1873 crash. Anglo-Austrian Bank money was key to developing the Galician railway which, in partnership with the Rothschild/Hapsburg family tracks to Trieste and elsewhere, provided the backbone for the White Slave Trade from 1850 onward.

Detail of the Duff Gordon Sherry plate: In this scene, depicting a tavern some time in the 1880-1890s, the serving wench is tight-corseted according the the style popular among wealthy lower-class women, prostitutes and Sisi of Austria. Wine bars were a favorite cover for prostitution at the end of the 1800s, alongside theaters and coffee houses.

The female figure celebrated on the Duff Gordon Sherry plate is a high-class call girl and stage personality Agustina Otero Iglesias.What is truly remarkable about her career was her access to johns:

“La Belle Otero:

The woman is La Belle “Bella” Otero (1868-1965). Born Agustina Otero Iglesias, her family was impoverished and at the age of fourteen she left home with her boyfriend and dancing partner and began working as a singer/dancer in Lisbon. In 1888 she found a sponsor in Barcelona who moved with her to Marseille, France in ordr to promote her dancing career. She soon left him and created the character of “La Belle Otero”, fancying herself an Andalusian gypsy. She wound up as the star of the famous Folies Bèrgere production in Paris.

Within a few years, Otero grew to be the most sought after woman in all of Europe. She was serving as a courtesan to wealthy and powerful men of the day. She associated herself with the likes of Prince Albert I of Monaco, King Edward VII of the United Kingdom, Kings of Serbia, Kings of Spain as well as Russian Grand Dukes Peter and Nicholas, the Duke of Westminster and writer Gabriele D'Annunzio. Her love affairs made her infamous and were the envy of many other notable female personalities of the day.

Otero retired after World War I and purchased a mansion and property in France. She had accumulated a massive fortune over the years bu she gambled much of it away over the remainder of her lifetime. She lived out her life in a more and more pronounced state of poverty until she died of a heart attack in 1965 in her one-room hotel-apartment in Nice, France. “

Luis Mazzantini: “The bullfighter is Luis Mazzantini (1856-1926) who was an infamous Spanish bullfighter who rose through the bullfighting ranks to become a national hero. He was recognized world wide and made appearances in Cuba and Mexico. After his retirement he became a politician, writer and patron of the arts up to the time of his death.”

Mazzantini, from a bourgeosie family, got a wild hair later in life and dropped his sober career for the bullfighting arena. He was well know for alledged Freemasonry connections, which were widely associated with political “fifth column”-type subterfuge during his lifetime.

LDG’s “personality dresses” appealed to upper-class and rich working-class women (prostitutes/actresses) alike. Soon LDG was designing “lingerie”— undergarments designed to be seen— for London’s nouveau riche and high-class call girls. The Folies Bèrgere production in Paris (see the Otero image above) was one of the outfits that inspired Flo Ziegfeld’s ‘Follies’ which LDG would eventually costume.

Otero would have been heavily in debt to her well-connected pimps by the time she was servicing King Edward VII, et alia. It was not uncommon for sex-workers to be recruited at 14 years old and often much younger. (Prince Andrew’s behavior is not so out of keeping with that of his forebears.) That Otero was first groomed through a dance instructor ‘boyfriend’ is also typical of the Galician network, and was the case also for Budapest’s infamous Fanny Reich. Readers may like to reflect on the dancing careers of Rat Pack star Fred Astaire (born Frederick Austerlitz); movie star George Raft; and British television mogul Lew Grade, Baron Grade (born Lev Winogradsky). No doubt the Duff Gordons were attracted to Otero because of her stage-personality as an Andalusian Gypsy. This manufactured image would have married the sherry and ‘oriental’-fantasies of fin de siecle scholars of Renaissance Hermeticism.

The contraband and trafficking networks which both the Glyns and the Duff Gordons would have been well acquainted with were staffed with people acculturated to boredello-chic, which was also celebrated by the Hapsburg ‘new aristocrats’ via the Wiener Moderne and ‘Young Vienna’ literary movement. LDG and her sister/co-producer Elinor Glyn were both vehicles for profiting from this culture, and agents combating social resistance to the ‘new aristocracy’ as represented by international financiers, traders and traffickers.

Therefore, that sherry-money (and New British East India Company-money!) would seek out someone like LDG to promote bordello-culture to press-hungry clothes-horses and their legion of followers is a more natural (and hermetical!) phenomenon than might at first be apparent. Much like Sisi’s beauty albums, the glitzy LDG fashion image gave little indication of the rot which lay beneath.

—

P.S.

Slavery is a worse problem now than it was in 1860. In our modern globalized economy there are many times more enslaved people than at any other time in recorded history. Most slavery victims who come into contact with law enforcement are migrants, and/or LGBT and/or children who were previously victims of sexual abuse. (The later two groups being predominantly targeted by pimps.) Victims of emotional trauma are more likely to be exploited by traffickers, as they are cults/ “high control groups.”.

The Global Slavery Index organization estimates there are 400,000 slaves in the USA at any given time, but they don’t explain how they arrived at this figure— it appears they rely on a handful of US law enforcement statistics. Since most slaves are migrants and there is little political will in Washington D.C. to prosecute immigration offenses, an accurate estimate of US’s enslaved inhabitants is likely many times higher. Another such organization, Exodus Road, expects to find slavery wherever migrant labor is common. The reality is there are more slaves in the USA now than there were in the 1860s— we’re just far less honest about it.

Slavery is more common per capita in the developed world than most of the developing world. It is more profitable to keep modern slaves in Europe or America than it is in Africa or South America. The exception here is Asia, where most slavery happens. Imported goods like laptops, computers and cellphones as well as apparel and clothing accessories are the goods most likely to be made by slave labor. It’s companies like Apple Inc.; the F.A.N.G. technology moguls; and clothing magnates like Jeffery Epstein’s employers the Wexlers who benefit from modern slavery and who advocate for the non-enforcement of immigration laws and open trade with slave economies.

Is life for a modern slave/ ‘migrant’ better than for a slave in the 1860s or 1880s? The average purchasing price for an enslaved person in 1886 in was US$ 40,000 in current prices; just before the US Civil War it was US $25,000; and it’s US$ 90 today. Human traffickers have never had it easier.