The National Salesgirls Beauty Contest

On a website filled with stories of cynical undertakings, ‘The National Salesgirls’ Beauty Contest’ (NSBC) stands out among the most cynical in Leon Goetz’s story. This contest represented a truce between warring NYC and Chicago sex-trade interests, a sort of Witches’ Sabbath held over the body of a seventeen year-old girl. In this post I’m going to detail the fighting that led up to the NSBC; the personages involved organizing the contest; and the marketing history which birthed the monstrosity.

It should be known from the outset that Edith May’s win was probably stacked. At least one of the NSBC judges had a business relationship with William Wesley Young; a few years prior Young’s family had gone into business along side Edith May’s uncle to establish Monroe’s famous Cheese Days event. It is not clear to me how far Edith May understood this herself; my guess is that by the time she was dining with a “Mr. Young” in NYC, she understood what was up. Her ‘prize’ was a short contract at Ziegfeld’s Follies and a role in an unnamed movie to be produced by the Mayflower Film Corporation. At some time during this period she had a photo shoot with Alfred Cheney Johnston; she left NYC (two weeks early judging by her day-planner) and never desired to return.

Details of this contest were broadcast nationwide through “NEA”, the “Newspaper Enterprise Association”, a syndication concern which hawked the writing of journalists like Zoe Beckley, a.k.a. “Friend lady”, who acted as Edith May’s minder and anonymous press agent during the NYC experience. Publicity stressed that NEA was the originator of the contest, but this was untrue. The contest was organized through a partnership between Photoplay Magazine, which was partly owned by Dr. Wilbert Shallenberger, and Flo Ziegfeld’s girlie enterprise.

Excerpt from Photoplay Magazine advertising section, June 1920. The listed owners of Photoplay were: E. M. Colvin, R. M. Eastman, J. R. Quirk, J. Hodgkins, Wilbert Shallenberger.

The pairing of Ziegfeld and Shallenberger caught my attention, because only six years previously the three Shallenberger doctors had lost business partner Charles Hite under suspicious circumstances when they tried to build a “dance hall” in Ziegfeld territory. In 1914 Mutual Film, the Shallenberger’s investment vehicle, opened ‘The Broadway Rose Garden’ in NYC’s theater district, which featured all the amusements which at that time were well-known covers for prostitution: dance hall/bar/movie theater/spa/restaurant. The Rose Garden was marketed right next to the Follies in ‘cabaret’ trade press.

Mutual Film entered the NYC cabaret market without the necessary protection. After contractor troubles; delayed ‘grand openings’; and losing the Garden’s key submarine film premiere to the National Press Club, Hite died in an unexplained automobile accident. The Rose Garden fared little better— it closed before 1914 was out, lasting maybe six months in operation after hundreds of thousands of dollars’ investment.

In an eerie foreshadowing of Hite’s death, his Edison Trust competitors’ mouthpiece Motography reported that:

Motography, August 1912. Motography would shortly be renamed Exhibitor’s Herald.

The early film business was a violent undertaking where no business concern was too respectable to shun bloodshed if they though it would protect their investments. Hite and Mutual Film were not only edging in on Ziegfeld’s girlie business, as independent film producers they were undermining Edison profits, too. (Edison produced a selection of uncatalogued films which were marketed to bordellos— he was no stranger to the sex-trade either!)

The Shallenbergers didn’t take any of this lying down. Prior to 1917 they used their Photoplay mouthpiece to lampoon their competitor Ziegfeld, here are some examples:

[Photoplay, March 1916] A comic piece imagining the future of the movie industry in 1940, through the diary of future starlet.

September entry for the “Biography of Babette Butterscotch, The World’s Greatest Movie Actress in twenty years’ time.

Even more vicious was this gem from Photoplay, which appeared the following April:

Photoplay Magazine, April 1916.

Text accompanying above cartoon: “Until the moving pictures became a craze, opening up a new field for actors, the various theatrical clubs were virtually deserted at the normal breakfast hour. For years J. Clarence Hyde, general press agent for Klaw and Erlanger [Ziegfeld investors], coffee-and-rolled alone in the grill room of the Lambs Club, Mr. Hyde by the rigid rules of his office as laid down by the alleged “Octopus,” being obliged to report at nine o'clock. That made his first meal of the day in the club an exclusive ceremony. Now a dozen actors sit by him each morning-- all recruits to the films.

At daybreak you may see hurrying from the Lambs Club, William Roselle, addicted on the screen to “dashing juveniles.” He takes the subway to 177th street, snatches a hasty breakfast at a delicatessen shop in the Bronx, climbs a long hill to the old Biograph Studio, and labors all day in the support of Billie Burke. Harry Weaver, who played Simonides in “Ben-Hur” for so many years, is another member of Miss Burke's company.

As for Miss Burke herself, she motors down from her mansion at Hastings-on -Hudson every morning, usually meeting her husband, Mr. Ziegfeld, on the road just getting home from his “Midnight Frolic” at the Danse de Follies. That is, Miss Burke as a rule makes the early-morning journey. One day last week she had not arrived by ten o'clock, and her director telephoned her home. “No really, I can't come down this morning,” replied the actress sweetly.

“Ill?” asked the director solicitously.

“Oh, dear, no,” answered Miss Burke, “but two of my chauffeurs are, and we are short, only three of them being available.”

Before she entered the movies Miss Burke worried along with two chauffeurs. The increased travel and revenue resulting from her film engagements now make five indispensable, according to her luxurious calculation.

The increase in the number of motor cars owned by the theatrical profession generally is an unmistakable sign of the enhanced prosperity among playerfolk since the advent of the movies. In the old days few members of the acting classes except vaudeville headliners and Ziegfeld chorus girls were able to afford cars.”

Apart from struggles with NYC mafioso, Chicago film-men had their own share of in-fighting. Mutual Film, at the start of 1916, signed Charlie Chaplin when his Essanay contract expired— Chaplin made US $10,000 a week with this deal. However, the four months prior to the signing had been full of gangland-style drama. The mob backing Chaplin had threatened Robert E. Eastman— one of the owners of Photoplay alongside the Shallenbergers— when Eastman pulled out of a book deal that would have increased Chaplin’s publicity and therefore bargaining power come January. While remembered for his charming slapstick comedy, Charlie Chaplin was not a charming person: he kept the company of men like would-be socialist dictator Egon Erwin Kisch— who also happened to be eyeball-deep in Prague’s prostitution underworld, a stronghold of the Austro-Hungarian/Galician International Organized Prostitution network that features heavily on this website. Here’s an article explaining Chaplin’s mafioso-style dealings, according to friends of Eastman:

The Chicago Tribune, September 15, 1915.

Threatening Eastman was a ballsy move on the part of Chaplin and his hoods. Eastman was president of one of the preeminent magazine publishing concerns in the world, the W. F. Hall Printing Company. From the Encyclopedia of Chicago:

Hall (W. F.) Printing Co.

William Franklin Hall, an Indiana native who worked as a journeyman printer in Chicago during the 1880s, founded his own printing company in 1893. By 1910, Hall's company employed about 400 people at its plant on Superior Street. During the 1920s, with about 2,000 workers, Hall was one of the world's leading printers of magazines and catalogs. Hall continued to prosper during the next few decades. By the 1970s, it was still a leading U.S. printer, with about 5,000 employees in the Chicago area and over $100 million in annual revenues. In the 1980s, after it was purchased by the Krueger Co. of Arizona and Ringier AG, a Swiss firm, Hall closed its main catalog plant on West Diversey Avenue and moved many of its printing operations to Tennessee and Mississippi.

The other Photoplay owners Edwin Colvin and James R. Quirk were employees of Eastman at the Hall Printing Co. Eastman’s control of this printing concern put him in the same league as notorious Austro-Hungarian influencer and press magnate Rudolf Sieghart, another freemason according to Emperor Karl/historian Elizabeth Kovacs, and long-time beneficiary of Hapsburg largess.

From the obituary of Robert Eastman. The Chicago Tribune, Novmeber 24th, 1932.

The Chaplin gang were well organized: a suggestive, finger-nibbling photograph of the girl on call to do Chaplin’s dirty work, Cecelia M. Virginia Davis, was provided to newspapers nation-wide in time to smear Eastman. Here’s the ammunition:

From the Kingston Daily Freeman (Kingston, New York), Monday September 20th, 1915.

Moffett Studio, which supplied the photo above, was Chicago’s leading theatrical photographer and a strange choice to shoot the supposedly NYC-based Davis. Moffett was shortly afterward acquired by Underwood & Underwood, employers of Flo Ziegfeld’s n’er-do-well brother, who in 1921 was green-lighted to document US labor activists in Soviet Russia. Besides being favored by Chaplin’s crowd, Moffett was patronized by leading Chicago newspapers and the 1912 Republican National Convention. These tony contacts weren’t enough to cover the studio’s dark side though, according to the University of South Carolina’s “Broadway Photographs”:

However, the arrest by the F.B.I. of [Moffett] studio employee Earnest D. Wallis for possession of photographs of classified plans for the A bomb in 1947 fatally damaged the studio's reputation.

In the 1940s, Underwood & Underwood sold Moffett Studio to the partnership of Robert T. McKearnan and Jack Russell. McKearnan took over complete control in the late 1950s.

Was Charlie Chaplin’s kneecap-breaking worth it? The contract Chaplin negotiated with Eastman’s business partner Freuler was eye-watering, it was described as scandalous, and at US $10,000 a week was more than any film actor had earned before. Despite Freuler publicly claiming Chaplin was worth it, Mutual would be functionally dead two years later. By that time Chaplin had jumped ship.

With Chicagoans fighting New Yorkers and each other, 1915 was a bloodthirsty year in the early film biz; owners of Photoplay and Motography were battling so hard that perhaps they didn’t hear Southern California begin to rumble.

Five years later, in 1920, the scene was very different. It was Motography, now titled Exhibitors’ Herald, that published the inside scoop behind Edith May’s NBSC/Photoplay win. The reason for this new amicability was financial: both NYC and Chicago interests were suffering. By 1914 the Edison Trust had been neutered and in 1917 James Quigley, a staunchly Catholic partner to the US government’s war on early films’ “porn problem”, bought Edison’s Motography. Mutual Film had also lost its business edge by 1920 and the Shallenbergers were desperate to protect what was left of their investments. The new giant in the business was First National, which had poached Mutual’s top star Charlie Chaplin in 1917 and acquired Mary Pickford in 1918. Ziegfeld was struggling to translate his stage-success to the more profitable silver screen. The fighting had to stop; it was time to combine the power of three.

The National Salesgirls’ Beauty Contest was from the beginning an advertising exercise designed to promote the brand-new Mayflower Film concern (from the ashes of Mutual) and Ziegfeld’s girl-show-cum-movie-starlet-factory. Beyond this, however, it was an innovative experiment in marketing, as explained by Mayflower’s general manager John W. McKay on Christmas Day, 1920 (Exhibitors’ Herald):

At Mayflower's executive conference last spring, it was decided that something should be done to sell the name of the Mayflower Photoplay Corporation to the public and at the same time promote patron-pulling interest in productions yet to be made.

Of course this was putting the reverse-English on the entire marketing situation, for usually the procedure is to make the picture first and worry about promoting it afterward. So because of its radical nature, we decided to give this scheme a novel propaganda treatment and see what the blood-test registered afterward. If the experiment succeeded, the plan was then to be adopted as a policy to be applied to all Mayflower-presented pictures.

…

This contest appealed particularly to women readers, and since women constitute the majority of picture audiences the campaign was 100 per cent effective from an exhibitor's standpoint... But the greatest benefit of all will accrue to R. A. Walsh and Miriam Cooper because the names of these two will be fixed indelibly in the minds of not only the 20,000 shop girls who entered the contest but their several hundred thousand relatives and friends, with the result that these people will always be interested in Walsh productions featuring Miss Cooper.

Here’s McKay’s full article:

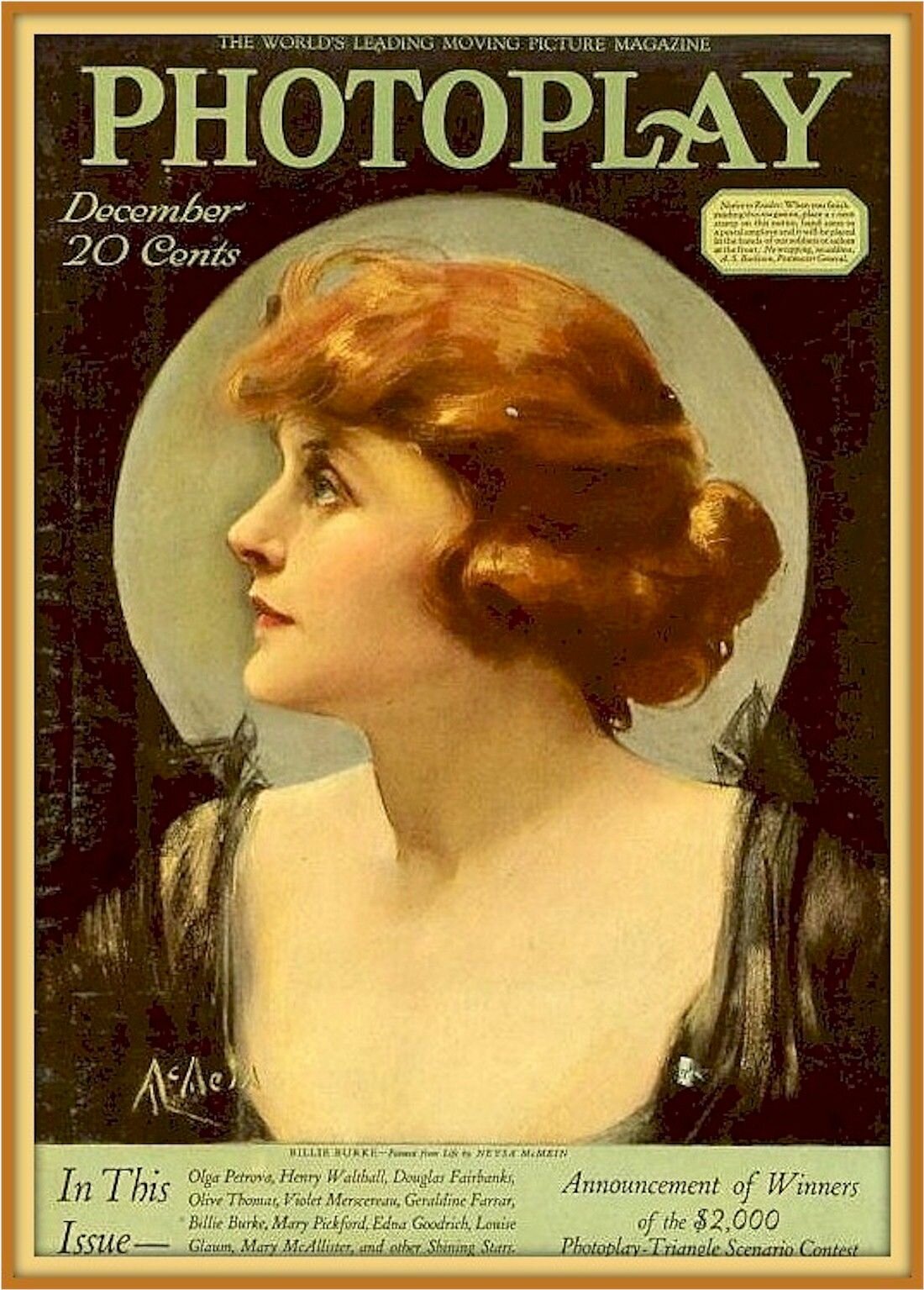

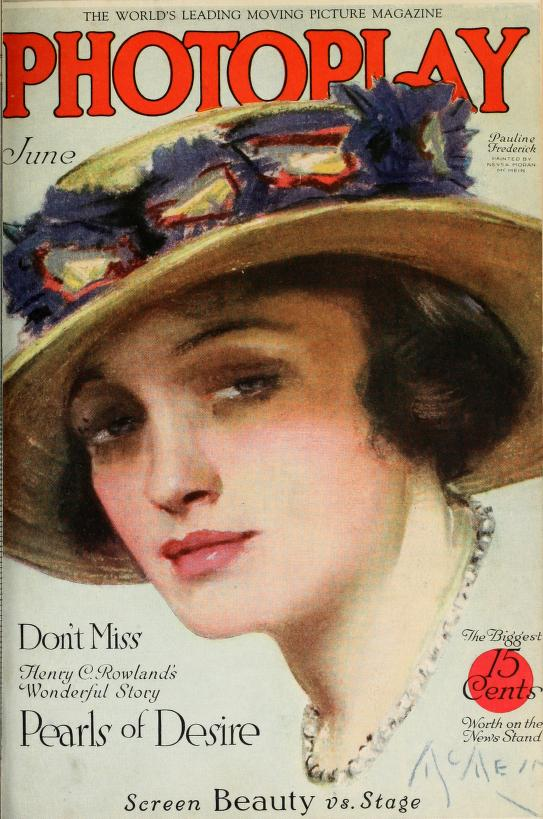

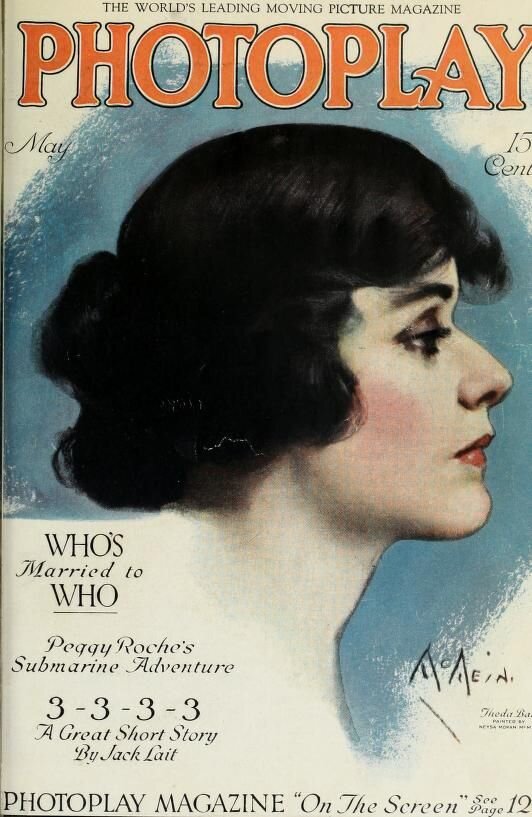

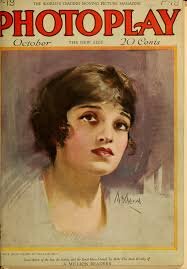

In the above article, McKay makes it sound like the idea for the beauty contest was originated by Mayflower. This is misleading, as Photoplay Magazine ran an almost identical contest in 1915 called “The Beauty and Brains Contest”. The NSBC was a Frankenstein recreation of Photoplay marketing know-how; Ziegfeld sex and glamor; and old Mutual Film starpower repackaged as ‘Mayflower’. This three-part effort was reflected in the make-up of the judges’ panel: Photoplay editor and publisher James R. Quirk (Eastman’s representative); illustrator Neysa McMein; Flo Ziegfeld; Ziegfeld photographer Alfred Cheney Johnston; and R. A. Walsh, the guy who played Pancho Villa in Mutual Film’s 1914 German propaganda flick “The Life of General Villa”.

I want to make it absolutely clear to readers that the Mutual Film and Ziegfeld sides to the NSBC had more in common than just film-making. Edith May’s beauty-contest win put her at the center of a partnership between previously warring pornography— and almost certainly— prostitution concerns.

Ziegfeld got started in the showgirl business using money earned from exhibiting his ‘wife’ Anna Held. Held and Ziegfeld were ‘married’ through one of the common-law unions that typified relations between pimps and prostitutes in the Galicia (Poland)-based international prostitution network— the most powerful prostitution network in the world at that time. Using the money from Anna, who he left in her mid-thirties (the end of a women’s marketable life as a prostitute), Ziegfeld set up his Follies troupe. Like many bordellos of the period, Ziegfeld kept a record of naked photos of his employees, a collection maintained by his in-house photographer Alfred Cheney Johnston. At this time prostitution was not legal in the USA and it had to be carried out under the guise of other professions, typically entertainment-related ones.

Ziegfeld’s ‘in’ to the girlie business was his father, who having worked as an agent for the US military band in German-speaking lands, was well-connected in the international traveling musician circuit, which Austro-Hungarian police identified as a primary vector for ‘white slave’ trafficking. Recruiting enough new prostitutes was a constant challenge for the pimps and traffickers.

Wilbert Shallenberger, who the above ‘statement of ownership’ names alongside editor James R. Quirk, R. M. Eastman, E. M. Colvin and J. Hodgkins as owners of Photoplay, was an itinerant doctor who specialized in venereal disease and worked the railway lines between Chicago and Waterloo, IA.

At this time the Galician/Austro-Hungarian prostitution network was run as an extended family enterprise and controlled by medical doctors who specialized in venereal disease. This network opened brothels along railway lines and used the trains to transport sex workers, which happened every few months in order to keep product ‘fresh’. Prior to WWI, the monthly global traffic in these women numbered in the thousands. The actual number of prostitutes is not known, but to give readers an idea of the scale of the enterprise, historian Edward Bristow notes that one Sri-Lankan-based Galician madam bragged about purchasing over 1000 European women for her bordello to date. The demand for women and girls from this network was voracious. Pimps and traffickers were constantly struggling to met bordello-owners’ requirements.

Wilbert Shallenberger was never convicted of pandering to my knowledge, but he and his brothers had enough capital to invest alongside banking heavyweights Kuhn, Loeb & Co. in John Freuler’s Mutual Film concern— and the Broadway Rose Garden. Given Wilbert Shallenberger’s profession and lifestyle, this amount of capital is hard to explain outside organized prostitution.

Interestingly, in 1921 Edith May’s patron Leon Goetz would be indicted under the Mann Act, weeks after making a film about Edith May’s sexually adventurous experiences with the Ziegfeld/Mutual/Mayflower concern. The Man Act was designed to combat international organized prostitution. Leon’s indictment was not made in connection with Edith May, but with another girl who he had hired as a pianist for his Monroe Theater. This young women claimed Goetz had trafficked her to Janesville, WI for immoral purposes. The nature of the indictment, and the business affairs of Edith May’s NYC/Chicago patrons raise uncomfortable questions about Leon’s interest in local women, and may explain why he was run out of town despite not having been convicted of any crime.

The value Photoplay brought to the NSBC was based on years of marketing experience. In October 1915 Photoplay ran a contest very similar to the NSBC, called “The Beauty and Brains Contest”. The prize was a career in the movies, naturally. This 1915 contest was overseen by William A. Brady, owner of the World Film Corporation, who we met before as Woodrow Wilson’s anti-porn tsar, appointed to combat early film’s “porn problem” after WWI. William A. Brady was also an investor in Ziegfeld’s Follies. This is how Photoplay chose to advertise “Beauty and Brains”:

Photoplay, October 1915.

“Moloch” was an ancient Canaanite god who demanded child sacrifices. (The title image is of a statue of Moloch outside Rome’s Colosseum.)

Two months after announcing the Beauty and Brains contest, Photoplay ran a fictional story titled “The Chorus Lady” about a salesgirl who runs away to become a chorus-line dancer, is sexually exploited and tries to use sex to further her career— she ends up ditching her sugar-daddy and marrying her lover, who forgives her dalliances. All these happenings are portrayed in a titillating way. The similarities between “The Chorus Lady” and the way Edith May was marketed in 1920 are obvious.

The fact that “salesgirls” were the protagonists in both “The Chorus Lady” and the news-fiction of Edith May’s contest win reflects the historical reality of recruiting for the international organized sex trade. As documented by historian Edward Bristow, young, poor women who worked in retail or as servants in wealthy houses were prime targets for pimps. The combination of drudgery, naivety, and exposure to luxury they could never otherwise afford was good psychological ‘priming’ for sex-trade recruiting. Of course, once girls were inside the network, a variety of physical, emotional, psychological and legal methods were available to make it very hard for them to leave. The pimps (men and women) always held all the cards.

Photoplay itself was the print incarnation of these psychological priming factors. I will point out to readers that the thousands of applications Photoplay received through both contests, applications that included addresses, pictures and psychological-profiling type material, would have made human traffickers’ mouths water. All they would have had to do was send over their local ‘Leon Goetz’-type character to groom likely targets.

Such beauty contests’ attractiveness to organized crime aside, “The Chorus Lady” is probably the best indication of what Leon Goetz’s lost film about Edith May, “A Romance of the Movies”, would have been like. The following images are from “The Chorus Lady”, you can follow the story line from the images alone:

Photoplay, “The Chorus Lady” December 1915. 1/7

Photoplay, “The Chorus Lady” December 1915. 2/7

Photoplay, “The Chorus Lady” December 1915. 3/7

Photoplay, “The Chorus Lady” December 1915. 4/7

Photoplay, “The Chorus Lady” December 1915. 5/7

Photoplay, “The Chorus Lady” December 1915. 6/7

Photoplay, “The Chorus Lady” December 1915. 7/7

I’ll wrap this post up by pointing out the Neysa McMein, the only skirt on the judging panel, was a so-called feminist who regularly contributed cover artwork to Photoplay and William Wesley Young’s Good Housekeeping. (You can see some of her Photoplay covers in the slideshow below— these colorful, stylized pictures of starlets contributed to the deceptive glamor that targeted women like young Edith May.) McMein occupied the artist’s studio next to Alfred Cheney Johnston’s, so her involvement with the NSBC is easy to explain. By 1917, when Mutual lost its teeth, Photoplay printed numerous, cloying stories about Ziegfeld and Burke’s domestic life, portraying the pair as a power-couple who had it all. Modern scholars have sought to represent Burke and Ziegfeld as crusaders for women’s empowerment, but I see things a little differently.

I think the only real champion of human rights in this story is Edith May, who had enough of a moral compass to run away from the fiery jaws of Moloch.