Mrs. L's Battleships

In 1920 a Monroe, WI teen named Edith May Leuenberger won a nation-wide beauty contest and was proclaimed “America’s Prettiest Salesgirl”. Part of her prize was a 6-8 week stint as a chorus girl in Ziegfeld’s Follies— an highly-publicized path to movie stardom at this time— as well as the promise of a leading roll in a film, title unannounced, to be produced by the Mayflower Film Corporation. Mayflower never got off the ground and the film never materialized. What Edith May did get was a serialized, nationally-syndicated column describing her Ziegfeld experience and ghost-written by Zoe Beckley of the Newspaper Enterprise Association (NEA). NEA was the cover organization for the Ziegfeld Follies and Photoplay magazine editors who were the real driving force behind the contest.

New Castle Herald, (New Castle, Pennsylvania). November 18th 1920.

It was entirely in keeping with contemporary business practices for fledgling or independent film producers to partner with the newspaper press to create “stars”. Before 1909, film production companies were reluctant to publicize actors, while actors feared harming their stage careers by appearing under their names in films, which theater operators rightly recognized as dangerous competition. It wasn’t until Max Linder teamed up with elements of the French and Argentinian press to publicize himself— as a fencer not an actor— that Pathé Frères executives realized the marketing potential of publicizing leading players’ names. [1] Carl Laemmle exported this strategy to the USA when he chose to publicize Florence Lawrence— formerly “the Biograph Girl”— under the name for which she became famous. Laemmle surrendered some power to publicly-recognized players like Lawrence in exchange for her commitment to his brand and control of a product to which the Edison Trust had no access.

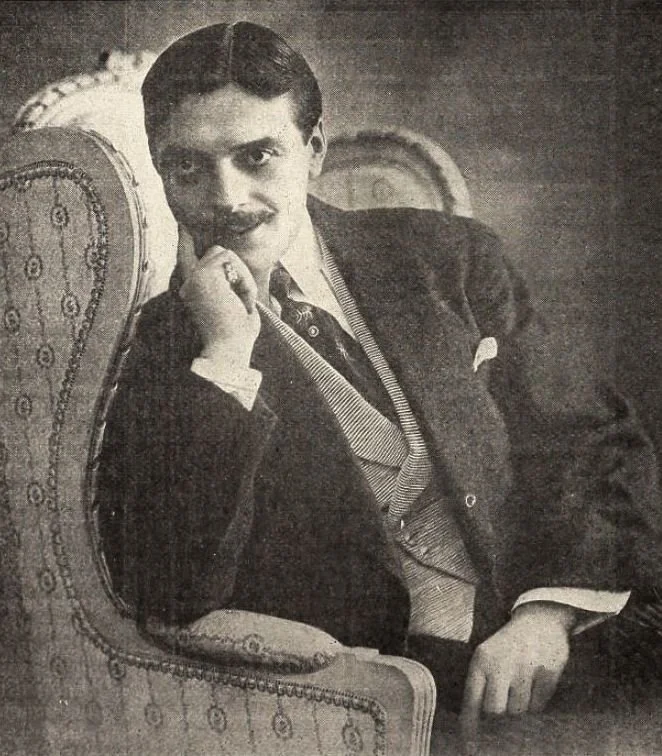

Max Linder in 1916. Linder was born Gabriel-Maximilien Leuvielle in 1883 in Gironde, France to a family in the wine business.

What Mayflower attempted to do with Edith May, and what Ziegfeld attempted to do through the starlet-mill he set up from his burlesque stage (coupled with nude photos taken by his employee Alfred Cheney Johnston), was the creation of a controllable and marketable “brand” using the face of Edith May Leuenberger. The fact that she was relatively unsophisticated made her marketable to “tired businessmen” and a good mark for an exploitative contract.

I do not think that Ziegfeld and the characters behind Mayflower were the only people exploiting Edith May, however. In my posts Who Was Virginia Whittingham? and The Humanitarian Cult I examined aspects of William Wesley Young’s dealings with British Intelligence and Roosevelt-connected manipulation of the socialist movement in New York City on the eve of US entry into WWI. During her Ziegfeld experience, Edith May recorded that she had dinner with a “Mr. Young” twice in one week. These dinners happened some time in October, the same month Young’s partner and founder of The Humanitarian Cult, Mischa Appelbaum, attempted to commit suicide in the face of mounting debts and the death of his sponsor Jacob Schiff.

Appelbaum’s key platform was that a Secretary of Welfare should be created, and appropriated the same amount of cash given for war-spending. Battleships, and their exorbitant cost, were one of his favorite tropes:

New York Times, October 13, 1915.

The purpose of the Humanitarian Cult is described in my post dedicated to it, but suffice it to say here that wealthy New York City financiers like the Schiff and Seligman families, Otto Kahn, and unscrupulous politicians like Teddy Roosevelt recognized that the socialist movement could be useful if properly managed. Misch Appelbaum was willing to work with these men, and switched his pacifist, pro-German stance to a hawkish anti-German one, thereby selling the war to his (alleged) block of 35,000 voting cult members.

While Appelbaum’s pro-German stance was not useful to these financiers after the war, Appelbaum’s pacifist message was exploited in service of the supranational agenda championed by Woodrow Wilson in the aftermath of fighting. The most famous result of this agenda was the creation of “The League of Nations”, a short-lived proto-United Nations. Representatives of NYC banking firms were very active at the Versailles peace negotiations where Wilson’s agenda was implemented, and were often informed of proceedings before the US Congress was. In fact, representatives of these firms were so deeply embedded in the negotiations that Congress held an investigation into their activities, however, few of these financiers bothered to heed the congressional summons to testify. What was vitally important to the bankers was establishing a preferential international financial climate.

This is where Edith May comes in, because her second installment to the “My Adventures in the Midnight Frolic!” column, ghostwritten by Beckley, contains material that might have come straight out of Mischa Appelbaum’s mouth:

Coming home we crossed the wonderful, beautiful New York bay and saw the ocean liners and warships. An ocean liner makes me want to shout for joy. The warship gives me a feeling of terrible sadness. I wish they weren't necessary. Whenever war threatens, why can't we all rush around on ocean liners to the different countries and talk to the people and settle things?

“Best View Of New York From City”

A sailor told us some of those warships cost over a million dollars and then in ten years they're no good anymore. I should think for a few million dollars we could hire somebody to think out a way to stop war, so we wouldn't need warships. And it wouldn't take ten years either.

The most glorious view of New York is from the bay as your boat makes ready to dock. It is then a fairy city with castles and towers of colored marbles and precious stones rising into the clouds. To think that men can make such marvels!

When I marry, I believe it will be to an architect or a builder of ships (not warships) , and we must have a house by the seashore like Mrs. L's.

The “Mrs. L” in question is supposed to be a relative Edith May serendipitously ran into in a New York restaurant. There is no mention in Edith May’s day-planner of such a meeting, nor that she had relatives farther afield than Madison, WI. Edith May/Beckley claims to have made a day trip to “Mrs. L’s” home outside of New York City. The only suggestion of such a trip in the day-planner is a note to “buy tickets” scribbled next to “Milbourne, New Jersey”.

The “Mrs. L” Beckley describes as a “relative” of Edith May’s sounds suspiciously like a member of the politically-connected Whittingham family, whose long history in agent provocateur politics is covered in Who Was Virginia Whittingham? The Whittinghams kept a country residence in Millburn, New Jersey, which would have looked something like the rural playground Edith May/Beckley describes:

Mrs. L's home is at a beautiful place on the coast of New Jersey. I have tried to imagine what the seashore was like but never pictured anything so delicious as it really is...

I had never seen any water bigger than a river. The immenseness of this stretch glistening blue-and-white meeting the sky on all sides gave me first a thrill, then a frightened feeling. I felt like running to mother.

But I soon got over the strangeness and liked it-- liked everything at Mrs. L's, from her car to the pussycat.

We had motor rides on smooth roads past handsome summer homes all facing the sea, with tennis courts out back and lawns like green carpet.

We played the pianola and the victrola and danced and had wonderful things to eat, and met loads of nice people, who seemed interested in me and kept asking if I ever wanted to go back to Monroe, Wis.

As upper-middle class New Yorkers in the 1920s, the Whittinghams would have enjoyed the lifestyle described above; Virginia was a concert pianist, so piano-play was to be expected. A cynical observer may reflect that this whirlwind of “love-bombing” and luxury may have been designed to hook Edith May into the type of work that Mischa Appelbaum was doing— a destabilizing psychological strategy often used by cults during the early stages of recruitment. Perhaps the promise of such a New Jersey lifestyle for herself— married to a fashionable architect or ship designer— was calculated to make it more difficult for the teen to leave Ziegfeld after a bad experience… and a bad experience we know she had.

I think it is to Edith May’s credit that she did not sign on for the “gloryfication” of a career with the Follies or to be a second version of Mischa Appelbaum. Somehow, the inexperienced seventeen-year-old sniffed rot at the heart of the New Jersey dream. When she did marry, it was to a cheesemaker in the landlocked hamlet of Brodhead, WI.

[1] The curious thing about this French/Argentinian press promotion of Linder was that the journalists in question seemed to have a precise knowledge of what their promotion of Linder would mean for him— one even quipped how Linder would receive worldwide fame once his name was known. Since film-actors names were never known (but stage actors were!) at this time, the anonymous correspondent’s prescience is interesting. That this ‘unorganized’ press campaign, conducted beyond Pathé Frères control, spanned two continents and just happened to involve France and Argentina, two prominent wine-producing countries, is notable given Linder’s family business.

Wisconsin State Journal, November 18th 1920.