Organized International Prostitution and Early Film's "Porn Problem"

One of the challenges faced by early film moguls was social resistance to their product— the industry had a “porn problem”. This wasn’t just an American problem, nor a European problem. The problem extended as far as the leading organized international prostitution network, a criminal enterprise which had its heart in the Austro-Hungarian ghettos of Galicia; arteries extending via railways to Trieste and Czernowitz (Chernivtsi, Ukraine); and from these cities to the rest of Europe, North America and farther afield to places including Argentina, Egypt, Turkey, South Africa and India. This network was organized along the same lines as the later cosa nostra: interrelated crime-families governed certain geographic areas and cooperated across borders to evade law enforcement, or assist law enforcement, as political conditions allowed. Besides prostitution, this network engaged in human trafficking (men, women, children), counterfeiting and smuggling.

I think it is somewhat misleading to call this international network “organized crime”, because it had so much sponsorship from the Hapsburg dynasty that it became an arm of the state. As Vienna struggled to keep control over subject territories in modern Poland, Hungary, the Balkans, and even in the Austrian homelands, the Hapsburgs increasingly turned to partnering with local organized crime groups for political information and public pacification. Where local police forces were not already corrupt, they were compelled to tolerate prostitution and even act as the “muscle” protecting the business interests of Vienna’s favored pimps, who in turn provided political support to the Emperor. Post-1848 Austro-Hungary was not a society headed by an aristocracy, but by a plutocracy which derived its power from an increasingly embattled imperial family. Vienna became the source of protection and largess for the most successful elements of Eastern and Central Europe’s criminal underworld.

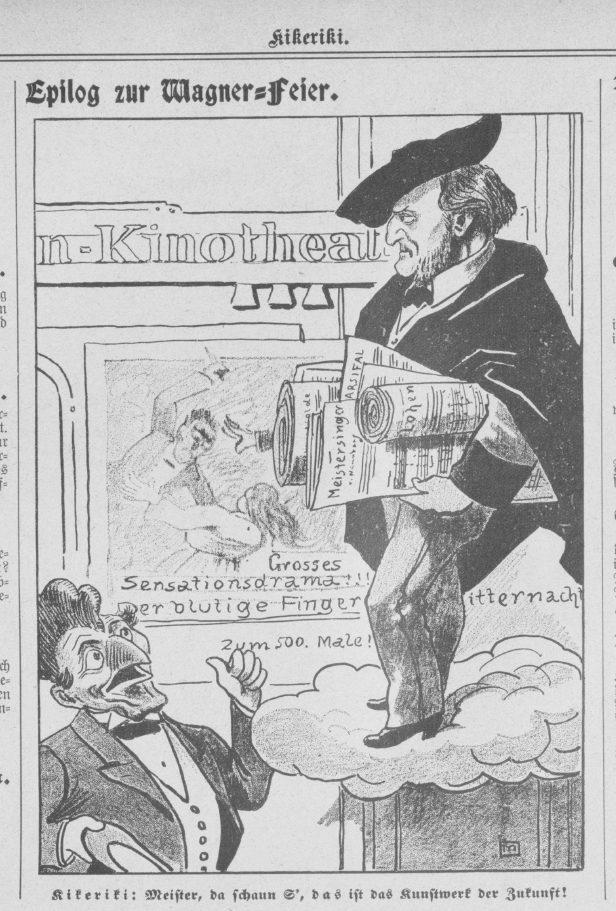

Needless to say, this trend in the way Austro-Hungary was run lead to epic culture-clashes over what was appropriate entertainment (public pacification), and what wasn’t. Below is a comic taken from one of Vienna’s leading humor magazines Kikeriki— note the date is June 1st, 1913, well before US entry into WWI:

Kikeriki, Vienna. June 1st 1913.

The heading reads: “Epilogue to the Wagner Celebration”. Behind the characters is a movie poster for a film titled “The Bloody Finger”, a “huge scandal-drama!” to be played at midnight. The rooster-headed figure is a personification of the editor named “Kikeriki/ Cock-a-doodle-do”, who speaks to the ghost of Richard Wagner. Kikeriki says: “Hey mister, see that there, that’s the Art of the Future!”

A great many people subjected to the Hapsburg form of government— both inside Austro-Hungary and outside of it— felt the type of art Kikeriki lampooned was culturally alien and morally degrading. This art was widely associated with the libertine aesthetic of the “Wiener Moderne” (1890s to 1918) which was more apt to see sex as a pastime, entertainment, than as a procreative act and the prerogative of marriage, which was the traditional Christian perspective.

This culture-clash spread as far as the pimping networks reached, and was the result of fundamentally different world-views. Dave Thompson is one of the leading scholars researching early pornographic films, and I think his world-view (as expressed in his 2007 book on the history of stag films) is fundamentally similar to that shared by Hapsburg-era beneficiaries to the sex trade:

“To cut away all the analysis and babble, let us agree that people enjoy looking at sex films for the same reason they enjoy looking at landscapes or cloud formations or precious stones. Because they find them appealing, because they are attractive, because there is a beauty in what they are witnessing that cannot be elsewhere. And just as we do not analyze why people like those other things, there is no need to analyze why people like to look at pictures of other people having sex.

Yes, there is a degree of avarice involved, jealousy perhaps, longing maybe. But do those same emotions not occur when one looks at an appealing museum exhibit? Or when a painter sets out to portray a sunset (for what is art, after all, if not an attempt to capture that which is otherwise ephemeral or at least immovable?) A man walking past a car showroom and gazing at the luxury he can never afford is experiencing the same basic emotions and sometimes sensations as if he was watching a sex film. The brain processes those sensations in a different manner to be sure, but if it could be bottled, the difference would be negligible.”

Thompson’s claim that he has the same emotional experience watching sex films as he has toward watching clouds, or viewing material items/status symbols like “precious stones” or luxury cars, is not a universal human experience, as he seems to believe it is. However, many people who benefited from the Hapsburg-era sex trade held a world-view similar to Thompson’s. They had their own ideas about what was tasteful (Lady Duff Gordon’s aesthetic); what made good drama and literature; what made good films. They knew how to entertain people who didn’t look for social responsibility in their entertainment and they knew how to make money at it— the pimps knew, at least. Rarely the prostitutes.

One of the defining features of the organized international sex trade was that “product”— sex workers— were constantly moved by the crime families. There were a number of reasons for this, mostly having to do with controlling employees/slaves and providing new experiences for customers, but one consequence of this relentless and untraceable traffic in thousands of people was an opportunity to smuggle illicit goods, too. From Thompson:

As in so many other distant lands, Argentina's expat community was certainly hallmarked by its disregard for the prohibitions of their homelands, and lived life as a near-perpetual party. The Argentinean stag trade was thus overseen by a German immigrant whose European contacts enabled the local product to travel afield as far as Russia, France, the Balkan states, South Africa, Germany and England. This same unnamed merchant should also be remembered for devising a most ingenious courier system. According to German historian Curt Moreck, “in order to remain undetected by the customs authorities, the films often made their way hidden in the underwear of international prostitutes.” The recipients of these exquisitely smuggled gems paid heavily for the privilege, although they were all but guaranteed a near unique return for their riches. Individual movies were made to order; a customer communicated his wishes, and an appropriate movie would be forthcoming. Even allowing for a sudden run on one particular theme, however, the customer base was so small that Moreck estimates no more than five prints were ever taken from any one negative, while the time and expense involved in shuttling movies across the oceans was such that any monopoly Argentina might once have claimed was soon to be cut down by local, European-based suppliers. In Italy, though the shadow of papal disapproval hung over almost any remotely enjoyable experience, an erotic-film industry was in place long before the production of the country's oldest surviving stag film, Suora Vaseline (Sister Vaseline) – shot around 1913 and devoted to the transgressions of a nun, a friar and a bisexual peasant named Andre.

Sexualizing Christian religious institutions and iconography was a curious preoccupation of early pornographers, which I discuss in Kahn and Ziegfeld: Glorifying the American Girl.

Thompson is talking about hard-core pornography in the quote above, which was often shown in secret rooms in regular film theaters (sometimes through ‘peep-holes’), in bordellos, or invite-only screenings. Small runs of such films could be very profitable, but small-run boutique films were not the norm. Pornography, both sexual and physical violence, was produced en masse by cinema’s most respected companies from the earliest days of the medium.

Argentinean movie historian Ariel Testori has suggested that such well-known institutions as Pathe and Gaumont, pioneers of the cinematograph, were responsible for introducing erotic movie making to the country, taking advantage of its distance from European laws and moralities to hire local residents to shoot erotic films for export elsewhere.

Even the Edison trust, which did a lot to make the smaller-time hard-core pornographers’ undertakings expensive through litigation, produced pornography:

Edison himself was no prude, Charles Musser, professor of Film and American Studies at Yale, once described the inventors ethic as “the more sex and violence the better,”1 and surviving footage certainly supports that claim.

Musser wasn’t misrepresenting the film industry leader, either:

Boxing, for example, was illegal in the United States at that time. The Black Maria [Edison’s film production apparatus] hosted a boxing match regardless, and the ensuing kinetograph was a massive hit. So were the studio's depictions of another forbidden sport, cockfighting. But Edison's most popular… efforts were his dancing girls.

In Summer 1894 just three months after the Kinetoscope made its public debut, the New Jersey resort of Atlantic City became the scene of the first ever “bust” of an “obscene movie,” when local authorities forcibly removed the kinetograph Dolorita’s Passion Dance from circulation, on the grounds that the dancer's very movements served to inflame passion…

… By the time the prohibition was issued, Dolorita’s Passion Dance was the most viewed kinetograph the parlor had ever hosted, while its notoriety was assured as early as May, when a Mr. W. J. D. Standifer of Butte, Montana, approached one of Edison's East Coast distributors to ask whether the company had any material that might appeal to clientele of that rough’n’ready copper mining town. Back came the reply: “We are confident that Dolorita’s Passion Dance would be as exciting as you desire. In fact, we will not show it in our parlor. You speak of the class of trade which want something of this character. We think this will certainly answer your purposes. A man in Buffalo has one of these films and informs us that he frequently has forty or fifty men waiting in line to see it.” Dolorita, incidentally, remained clothed throughout her performance.

Victorian reformers, censors and consumers of pornography were in tune with the fact that people didn’t need to be naked to be titillating; a reality that many modern commentators appear to miss. Innuendo, and what porn-insiders describe as “selling the sizzle not the steak” is often far more exciting. Then as now, anticipation of sexual gratification is what motivates the sex trade, the actual experience isn’t necessarily what keeps punters coming back for more.

… these short films were arousing, a point that was succinctly made in A Country Stud Horse, a stag movie dating from the 1920s. Here we see a man avidly watching just such a film on an old-fashioned Mutoscope (a peep-show contemporary of the Kinetoscope in which a series of tumbling snapshots fulfilled the illusion of movement) and vigorously masturbating while he does so.

Whether in his own imagination, or in reality, the film he is watching heats up as he toils, at which point a prostitute (introduced as ‘Mary’ by an accompanying caption) stops to “pick up some business”. This is not a far-fetched scenario, especially if we place the Mutoscope in an area where women such as Mary might well be touting for trade. Brothels and bawdy houses had a long tradition of employing dancers and actresses to entertain in their waiting room; in the second half of the nineteenth century, the better-appointed establishments built up vast collections of erotic daguerreotypes and photographs, for the amusement (and, ultimately, stimulation) of their patrons.

To the entrepreneurs of the nineteenth century, a moving picture show was simply the logical next step, all the more so since the novelty of the medium might well have enticed some clients to come even more regularly than they otherwise would have, simply to view the films — a phenomenon that contributed to the early growth and popularity of the movies. According to Charles Musser, “the Edison staff often filmed coochee-coochee dancers”. Significantly, few of these films were ever listed in Edison catalogues, and then only long after their production. This suggests that a body of Edison films were circulated more or less clandestinely.

… Countless films of this nature were produced during the first years of film and, as audiences grew more sophisticated and technology further advanced, so the movie-makers galloped to stay ahead of the public's expectation.

Ironically, the very networks which distributed this pornography appear to be the main arteries through which pirated copies of Edison films, and the films of other legal producers, were distributed around the world. Catering to the bordello crowd quite literally undercut the industry power that Edison spent so much money to protect— the Hapsburgs would have done well to take note. From Kerry Segrave’s Piracy in the Motion Picture Industry:

A 1925 account reported that the US government was helping American movie companies to stamp out piracy in various foreign countries... The US government was to have assisted in running down piracy cases in Turkey, Venezuela, Colombia, other countries in South America and in several parts of Africa... According to a report from Richard May, American Trade Commissioner with the Department of Commerce, the pirating of pictures in Palestine had reached the point where the original producers could not dispose of their product to exhibitors.

Cuba, Mexico, Jerusalem/Palestine, and Poland were major copyright infringement centers, often using contacts in “the distribution offices of film producers in New York City.” Segrave describes a major Polish ring, which was well established by 1924:

Centered in Warsaw, the ring “borrowed” movies that were being legitimately shown in Vienna or other cities, made duplicate negatives during the night, and replaced the films before morning. Next, they made sufficient prints in Warsaw to supply the Baltic States, Russia, Bulgaria, Greece, Turkey, Persia, Romania, Poland and Egypt. Rosecan [a trade investigator working for the Pathe Exchange in New York] found that legitimate buyers of United Artists and Paramount movies were being beaten to the screens by at least several days by rival exhibitors who purchased through the bootleggers.

Pirate exhibitors were by no means small-time either, some even joined anti-piracy organizations as a cover for their activities much like bordello businessmen were known for joining abolitionist/anti-prostitution leagues, particularly in Trieste. Once a pirated film entered such a network, it would be sold throughout the world-- there are records of them even ending up in China.

When U.S. Government propagandists like film czar William A. Brady declared in 1919 that the film industry’s “porn problem” was a serious threat to American power and a key asset for Imperial German propagandists, they were throwing themselves up against a smuggling/prostitution network that had had state sponsorship from at least 1848 in Central Europe and many decades to entrench itself in the global economy. Compromise and cooperation were the order of the day.

Although Woodrow Wilson’s administration chose to target porn in 1919, in domestic America, film-based pornography had been in the cross-hairs of womens’ organizations for a long while. These womens’ groups had a surprising amount of political power, and as shown by Leon Goetz’s history in Monroe, WI and his consequent production of a Temperance film Ten Nights in a Bar Room, their agenda often won the day. It was through partnering with womens’ and mothers’ organizations that industry leaders such as Monroe-native John R. Freuler fended off strict community and federal regulation of film content.

As Freuler was no stranger to sexually exploitative films himself, this partnership was a cynical affair which ended up serving corporate interests more than those of the broadly-based womens’ groups. Anti-prostitution and anti-slavery activists in Europe sometimes found themselves in the same position: criminals would try to hi-jack grassroots movements (through moles and financial contributions) in an attempt to craft legislation or public debate that served the interests of those who benefited from the behavior activists tried to prevent. Sometimes such hi-jacking was successful, but always temporarily so. Discontent over clashing world-views remains a thorn in the side of the movie industry to this day.