Empress 'Sisi' and Prostitution

The history of early film is rooted in the political and economic situation of Austria-Hungary. The Hapsburg’s connection to international prostitution is white-washed out of their story, much as it is with scholarly histories of the movies. One of the most forward promoters of bordello-culture from 1860 onward was Elisabeth of Austria, wife of Franz Joseph from 1854.

When I first started looking into ‘Sisi’, I did feel some resistance to evidence of her prostitution-fascination. I also labored under the misapprehension that the Hapsburgs were essentially “reactionary” Catholics who didn’t understand the “progress” manifesting around them. I had the 1950s ‘P.R.’ version of Sisi in my head and I didn’t really want to let go of that— surely tainting her with prostitution was as dishonest and subversive as suggesting Huck Finn and Jim were gay.

A 1955 poster featuring Romy Schneider in the role she made famous.

Unfortunately, in the case of the Empress, such taints are not dishonest and are justly subversive. Elisabeth, one of the first “celebrity royals” who cultivated popular press, built her public image around a stay of 19th century prostitute culture: tight-lacing. According to her biographer Katrin Unterreiner, this turned Sisi into the type of empress whose picture soldiers would hang above their beds. [See Unterreiner, Katrin. Sisi: Myth and Truth.]

“Tight-lacing” was the practice of wearing a corset tied tight enough to narrow the waist down at least 6 inches smaller than it would naturally occur. In Sisi’s case, she tied it down to 16 inches, but 13 wasn’t unheard of, especially among women whose profession was the stage. An image of a 1860s German corset at the Miedermuseum in Heubach is below, courtesy of Redthreaded.com:

This is a linen corset from the 1860s, not quite like the one Sisi wore….

This is an image of Elisabeth tight-laced from 1862:

Elisabeth’s tight-lacing started as a protest against the duties and restrictions which her role as empress necessitated. She’d had three pregnancies in succession— by no means uncommon in her time— and had less than complete control over the care of her children. Her response was to stop having sex with her husband and flaunt the dereliction of her duty to produce heirs in an age where children often died before adulthood.

In Lieu of a Love Life: These paintings of Elisabeth were done by Franz Winterhalter in 1864, shortly after she stopped sleeping with her husband. They hung privately in the emperor’s study and were never publicly exhibited.

Winterhalter 1864/65. The second of the private paintings. Sisi’s hair was one of the things she fetishized in her press/public image.

The linen corset pictured above is not quite like the ones Sisi wore, hers were leather. This is an important point because leather corsets— serious cinch— were the corsets associated with Parisian prostitutes, according to David Kunzle, an art historian at the University of California. Leather corsets were so unusual that I couldn’t find an image of one from the 1860s— linen and cotton were what nice ladies wore. Sisi tied these leather garments so tightly that they were useless after a few weeks. We know this because of the 1913 tell-all book written by Sisi’s niece Countess Marie Larisch, a rather nasty character and persona non grata with Elizabeth after her son’s ‘suicide’, as Larisch had introduced the unstable Prince Rudolf to his teen mistress Mary Vetsera.

It is possible that Larisch’s leather corset gossip is a smear— a smear which could be easily dispelled with by checking records of Elisabeth’s domestic expenditure at this time for regular corset purchases from France. No one has done this. What we can be sure of is that Elisabeth’s obsession with her waist irritated her mother-in-law and for good reason. Contemporary doctors knew very well that this fad was terrible for women’s health. Social commentators decried the practice for encouraging licentiousness, selfishness and frivolity: “Tight-lacing is the ultimate proof of women’s irrationality and incapacity for higher work” (Saturday Review, 1869 as quote by Kunzle, Fashion and Fetishism 1982). Kunzle summarizes the prevailing social attitude:

Never “fashionable” in the sense of being generally acceptable to the wealthier classes, tight-lacing stands out as a minority cult which tended to cut across lower and middle-class boundaries... Its major concentration was probably among the lower-middle classes... although we also find occasional complaints that the bad example was set by the “so-called leaders of fashion” (none of whom is, however, identified or identifiable by name).

The tight-lacer stood in a very difficult position within a society generally and vocally hostile to the practice... In closing ranks against the enemy, they developed the identity and something of the psychology of an oppressed minority.

The accusation of tight-lacing was a serious one. It cannot have been easy for any girl or young woman, whatever her compensations in the form of male admiration, to cope with being officially branded as a depraved, criminal being, as a potential infanticide and willful destroyer of posterity. It is thus not surprising that few tight-lacers could admit publicly to the practice...

Elisabeth’s tight-lacing was not an accidental public ‘slip’ which was unfairly pinned upon her by an unsympathetic press, but rather an image crafted with the empress’ blessing. The strongest evidence for this is Sisi’s representation at the “Great Exhibition” in London— I think Kunzle means the International Exhibition of 1862, or “Great London Exposition” held in South Kensington:

The pro-corset party called upon an exceedingly prestigious example— that of the beautiful Empress Elizabeth of Austria, reputed to possess the smallest waist ever seen. Together with her portrait, her girdle had been on view at the Great Exhibition. A query as to the exact length of this girdle was answered by Miss Turnour, who, when she visited the Exhibition, had seen the exhibitor hold it up in his hand, “so beautiful, purple velvet stiff with rich gold thread, looking like a dog-collar when clasped.” Miss Turnour was even allowed to make a “frantic and futile effort” to close it round her own slender waist, and was enabled to certify the measurement to be exactly 16 inches; and the Empress was tall, 5 foot 6 inches.

The unspoken inference was, of course, that the Empress indulged in tight-lacing, which thereby acquired a social cachet otherwise totally lacking….

Kunzel reflects on what this little purple belt meant:

Why was an object with such scandalous associations put on public display? With her horror of publicity, especially as regards details of her personal life, it seems inexplicable that the Empress would have encouraged gossip around so intimate a matter as a waist-measurement. If the numerous biographies remain silent on this curious episode, is it because domestically the matter was hushed up? After all, in order to protect the imperial dignity the police actively suppressed stories of her equine acrobatics, and destroyed photographs pertaining to it. If the 16 inch belt was displayed with her permission and knowledge (and it seems hard to conceive otherwise) or, worse, on her personal initiative, was it intended as a provocation? Was it the bizarre symbol of or satire upon the exhibitionism to which the most adulated woman in Europe was subject?

I cannot speak comprehensively on Elisabeth’s religious convictions, but I can interpret her tight-laced image as would contemporary students of Renaissance Hermeticism, which included journalists and rich “Ringstrasse” newspapermen who broadcast her image. Elizabeth’s adherence to the tight-lacing “cult” was a projection of highly-developed will against the continuance of the Hapsburg dynasty, the power of which would be compounded by mimicry from her admirers— a sort of Mnemosyne-working against the family line.

Besides Sisi’s belt, the 1862 London Exhibition featured the work of designer William Morris, who became the darling of Vienna’s rich “Ringstrasse” Art Patrons during the “Avant Gard” period (1908+, but traces antecedents to 1890s). The most famous of these patrons are the Rothschild family, business partners of Kuhn, Loeb &Co and the Warburg family, but also notable among the newspapermen was the powerful art promoter/journalist Ludwig Hevesi. Hevesi wrote for the leading Liberal and Jewish-owned papers in Vienna, which were by far the most influential. By 1907 Hevesi’s patronage of (by then deceased) Morris and the anglophile aesthetic Morris represented had reached biblical proportions:

In 1906, aware of the Jewish romantic identification with British culture, Hevesi published a humorous piece on the absurd theory that Englishmen actually originated from the lost ten tribes of Israel. Regardless of these diversions,[Adolf] Loos did address Jewish romantic identification with England and Jewish collective memory through his structures as firm rejections of the Ghetto and in their historical relationship to ancient Egypt.

The president of the Royal Society of Arts, Manufactures and Trade (sponsors of the London Exhibition) at the time of the exhibition was William Tooke, a reform politician who liked to publish anonymously in fashionable periodicals.

Elizabeth’s preoccupation with bordello-culture didn’t stop with mimicking Parisian tight-lacing trends. She liked to collect pictures of beautiful prostitutes too. Sisi, as quoted by a modern artist with the same creepy obsession, Christina Catherine Martinez:

“I am creating a beauty album,” she wrote to her brother-in-law in 1862, “and am now collecting photographs for it, only of women. Any pretty faces you can muster at Angerer’s”—i.e., Hapsburg court photographer Ludwig Angerer’s— “or other photographers, I ask you to send me.”

One of Sisi’s photograph books, from 1862 according to ArtForum.

Martinez continues:

Elisabeth had a famously difficult time at court, spending most of her never-ending leisure hours clashing with her mother-in-law, sympathizing with the democratic yearnings of the people, traveling solo (whenever she could), and assembling a collection of some two thousand photographs. She organized these images into albums, which will be on view at Cologne’s Museum Ludwig in an exhibition opening October 24…

Sisi called her most remarkable compendiums “albums of beauty,” and I believe she had to in order to procure their contents—photographs of beautiful women. But the subtext of these images in the aggregate hints at something sexier and unspeakable, the early stirrings of a new affect that had yet to be named but was keenly embodied by the leg-flashing courtesans Sisi pored over (racier photographs were supplied to her by Parisian ambassadors). …

Sisi’s uncle, King Ludwig I of Bavaria, had his own “gallery of beauties,” which would have been familiar to the young princess. Ludwig commissioned these portraits of women and handpicked the models, who ranged from family members and fellow aristocrats to anonymous peasants. It was a public, patriarchal template for Sisi’s albums.

One of the performers featured in Sisi’s photo book, which also included “Mademoiselle Leonie” a corseted teen “variety artist” with a birch-rod and unknown dancers lifting up their skirts. See Unterreiner.

Elisabeth’s infamous beauty routine— she had her hair combed for two hours every day and that was just the start— was intimately connected with her political activism. She had her Greek Teacher Constantin Christomanos read and “philosophize” with her while this combing took place and for strangely occult-sounding reasons: so her “soul” wouldn’t leave through her hair into the fingers of the hairdresser.

After Sisi’s death, Christomanos would go on to edit the “Young Vienna”/ Wiener Moderne mouth piece Wiener Rundschau, which propagandized alongside Herman Bahr’s Die Zeit, Lothar’s Die Wage and other “Ringstrasse”-affiliated art journals. These journals celebrated famous prostitutes, erotic dancers and their idle, wealthy johns.

According to Katrin Unterreinter, the “Beauty Album” collecting was an extension of Sisi’s politics-laced beauty cult:

Elisabeth’s beauty cult is not limited to just herself— she is fascinated by every aspect of beauty and invests in a beauty album. She collects photographs of women she considers beautiful: Ladies-in-waiting, European rulers and also Ladies from the demimonde such as dancers and circus artistes. Elizabeth is fascinated more by radience and natural or unusual faces, not by beauty in its classic sense and, above all, irrespective of class or social parentage.

Elisabeth hated the aristocrats who surrounded her at court in Vienna— a centuries-long Hapsburg tradition— and her surviving diary entries/poems paint a very bitter picture of the young woman’s relations with her peers. Hapsburg police destroyed parts of Elisabeth’s diary after her assassination.

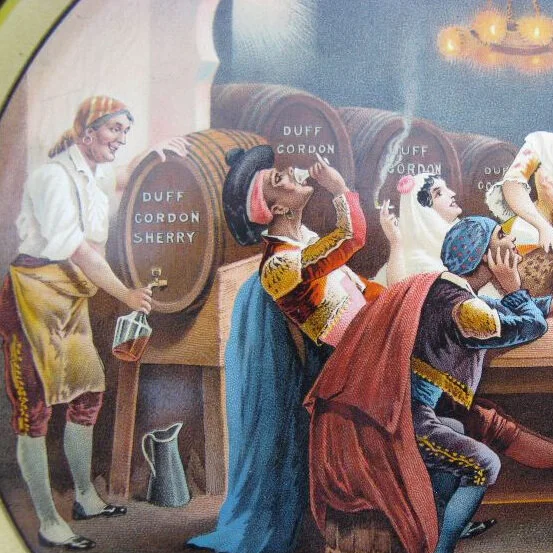

What Sisi did like very much however was money, and she associated with the nouveau riche during her solo trips around Europe’s pleasure zones in her imperial yacht. These wealthy friends included the Rothschilds and the Vanderbilts, to whom she would vent her depression. The Rothschilds were the developers of the railways that made the slave trade Sisi’s husband sponsored possible; later members of the Vanderbilt family were responsible for bringing Lady Duff Gordon’s “bordello-chic” to New York robber-baron wives and actresses— including our hometown Monroe, WI Ziegfeld Girl Edith May Leuenberger.

It’s sad when historical figures don’t live up to crafted ideals, but I think the truth is always most healthy in the long run. Sisi’s preoccupation with facets of bordello culture; and images of bordello culture; and bringing aspects of those images to life through her press-personality is simply an ugly fact— particularly so as her subjects suffered disproportionately due to this horrific trade. The fate of some of them in Istanbul was described by contemporary travel writer Samuel Cohen, quoted in Edward Bristow’s Prostitution and Prejudice:

“The inmates of the brothel are seated on low stools or on boxes or on low couches with almost nothing on in the way of clothes. Their faces are painted and powdered, but the haggard look in their eyes cannot be hidden. In almost every case, each prostitute sits in a small compartment not more than 20 to 24 inches wide with a wire netting in front facing the street. Some few have small windows... They permit the girls to call out to the passers by. In every house the 'Madame' sits near the door or close at hand to watch over the inmates. The whole scene is revolting.”

But naturally, those images didn’t make it into the beauty books…