Cosmo's Spooky Aunt: Lucie Duff Gordon

In my post on Lady Lucy Duff Gordon, whom I affectionately call “LDG”, I detailed how she and her sister Elinor Glyn worked together to promote the more liberated sexual mores which were valued among New York City’s and London’s nouveau riche. The sisters began their work in the 1890s and their legacy is the “mainstreaming” of bordello-culture in the Anglophone world. It is precisely this bordello-culture which early cinema sold by the bucketful, and why its champions like John Freuler and Leon Goetz faced so much backlash from wider society. Freuler, LDG, Glyn and Goetz, while from different countries and socio-economic backgrounds, were united as part of this cultural phenomenon.

While these twentieth-century icons brought bordello to the masses, they were actually building on a long-existing— and very strange— European sub-culture that had been nurtured at the highest levels of government wherever empire-minded monarchs reigned. This subculture was about power-building through hermetical means: it looked to the Near East for Ancient Greek political wisdom and such knowledge flowed into Europe along the same routes as white slaves flowed out. These slaves, typically women and children, staffed the harems and prostitution houses in Islamic lands— a practice common since Viking times that has never really ended. In the minds of absolutist rulers hermeticism/the occult, sexual exploitation of minors and slaves, and lucrative trade were conflated into an intoxicating dream of absolute power. The reality of life in ‘the East’ really didn’t matter, what mattered is how this culture was perceived by the rulers’ political allies. LDG’s ‘bordello culture’ was a mass-market rendering of this empire-minded philosophy, stripped of its obvious occult underpinning, and sold at 15 cents a ticket to American working class audiences.

Since the “It Girl” phenomenon was so heavily underwritten by LDG’s first investor and second husband Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon, it’s worth looking at where Cosmo came from. Let’s start from a mistake made by Teddy Roosevelt.

When LDG met Theodore Roosevelt on her 1909 American Tour, Teddy mistook her for her in-law, Cosmo’s long-deceased aunt, Lucie Duff Gordon— perhaps the president’s mind was on his new submarine fleet. President Roosevelt congratulated LDG on ‘her’ excellent “Letters from Egypt”, which Cosmo’s aunt had written over seven years during her excursions to Egypt, where she died at 48 years in 1869.

Lucie had ‘gone native’ and surrendered herself to ‘Egyptomania’, a stylized mixture of ancient folklore and local Islam, which was popular among Europeans in the later half of the nineteenth century. Her romanticized view of Egypt— and particularly its Bedouins— found fertile ground among wealthy reformers in the English-speaking world, so it’s not at all surprising that the British fashion designer was confused with the pseudo-Egyptian storyteller by the New York politician.

Lucie has been treated more kindly by modern historians than most Empire-era British expatriates, which is odd, because an examination of her behavior shows she was deeply involved with the building of the Suez Canal. While Lucie made cyclical trips to Egypt for her health, she was also intimately involved with the canal through her political reports on Ismail Pasha, the local potentate who was the project’s ‘business end’. The canal was opposed by the British government— though not by all wealthy British subjects— as it was French-dominated and financed through the French Rothschilds. French, Prussian and Hessian dignitaries graced the canal’s eventual opening.

While the French plans were ultimately successful, it took many tumultuous years for the project to be finished— years that overlapped with Lucie’s letter-writing. In order to try to derail Ismail’s efforts, the British government organized violent ‘black ops’ staffed by Bedouins and made public outcry against Ismail’s forced labor policies. Ismail Pasha openly rebuffed Lucie’s criticisms of him and Lucie claimed he had tried to kill her— which would have been easy, but it never happened. The canal however did happen, to the consternation of official British circles.

Down but not out, the British government tried other means. In 1875 (after Lucie’s natural death) excessive loan-taking bankrupted the Egyptian khedive and forced him to sell his 44% stake in the canal— much like excessive loan-taking had forced Austro-Hungary to sell state-financed railways at around the same time. UK Prime Minister Disraeli, along with help from the Earl of Derby, orchestrated the public purchase of the khedive’s shares. When in 1882 convenient local unrest gave the British the opportunity to seize the canal, Evelyn Baring, of the famous German-derived London merchant banking family, was given control of the waterway and its financing.

While by 1882 the British government had a firm grip on the Suez Canal, this outcome was far from certain in 1862 when Lucie’s residence in Egypt was set up by her mother’s friend Nassau Senior, himself part Ferdinand de Lesseps’ original 1855 entourage who collectively determined the line of the Suez Canal. Supported by a staff chosen by representatives of Senior, Lucie’s reports on Ismail were sent back to her husband, Alexander Duff Gordon, who then redacted them and published portions that met official British policies. On the quiet side, Lucie would host curious guests at her Luxor home, such as: a German explorer who focused on the lands of hostile Central African tribes (she protected his identity); an Imperial British Antiquities inspector (whose work she frustrated); and social commentator Edward Lear— a protege of the Smith-Stanley family, Earls of Derby, who were essential green-lighting Disreali’s purchase of the Suez Canal years later. These behaviors taken together lead me to suspect she acted as something of a double-agent, giving Downing street what it wanted but facilitating what would eventually become the purchase of the Suez Canal by wealthy British subjects.

But how did Lucy Austin end up in Luxor, acting as a front-line reporter on one of the most geopolitically important topics of her day? Below is an 1851 portrait of Lucie wearing a type of Middle-Eastern inspired costume— years before she ever meditated moving to Egypt. By the time this portrait was painted Islam- and Orient-flavored stylizations had for decades been popular among London’s radical set of wealthy intellectuals, freemasons, and assorted mystery-cult adherents. Lucie was an upper middle-class follower of the trends initiated over a hundred years earlier by women like Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, and even earlier than that by Queen Elizabeth I.

Lady Lucie (Austin) Duff-Gordon, portrait by H. W. Phillips (1851), courtesy of UK National Portrait Gallery.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu is famous for her inspiring the Divan Club, a libertine fraternity open to those who had traveled to the Middle East and who subscribed to the the sexual mores Lady Mary reported on from her travels. Because of the attention paid to her by another notorious drinking club, it is believed Lady Mary was sexually abused as a very young child, prior to her marriage into the (now notorious) Montagu family. However, the zeitgeist Lady Mary rode to fame found its genesis earlier in history, in the beginning of the Early Modern Period in Europe.

The tragic Lady Mary Wortley Montagu in “Turkish dress”, as painted in 1756 by Jean-Étienne Liotard, The portrait is part of the collection of the Palace on the Water in Warsaw.

The video below is an excellent piece of art-sleuthing by historian David Shakespeare who examines the “pregnancy portrait” of Queen Elizabeth I painted ca.1594-1604, wherein the sovereign wears a stylized Turkish/Ottoman/Persian dress. The forerunners to Lady Mary Montagu’s mystery cult contemporaries, students of hermeticism like QE1, looked eastward for esoteric wisdom to increase their power, as occult knowledge often entered Europe from Islamic lands via slaving routes. The queen kept a personal correspondence with Safiye, the mother of Ottoman sultan Mehmed III. Safiye was an Albanian slave-concubine who was procured at 13 years old by Princess Cameria to curry favor with one of her father’s successors— behavior not unlike that alleged against Ghislaine Maxwell, whose “very powerful” father was also from Eastern Europe. It is likely Safiye and Elizabeth shared psychological characteristics beyond those influenced by their status as heads of state, as Elizabeth had also been exploited by her ambitious step-father at around the same age as Safiye was procured.

Lucie more than likely shared similar childhood experiences to these famous women, and was brought up in an environment that viewed ‘the East’ in the same power-preoccupied way.

Lucie (Austin) Duff Gordon’s family (both biological and in-laws) were supporters of the political reform movement that ultimately lead to the replacement of Europe’s traditional aristocratic elite by the nouveau riche who patronized LDG. As a child Lucie Austin was the surrogate sister of John Stuart Mill, the famous economist and leader of the British East India company’s intelligence apparatus until the mutiny of 1857. Lucie’s mother Sarah Taylor— who was for some reason fluent in German— came from a noted Norwich family of religious dissenters (the Unitarian sect, which eventually evolved into “Unitarian Universalism”, as in the minister-backer of Edith May’s exploitation flick); while Lucie’s father was a vacillating character prone to Schwarmerei.

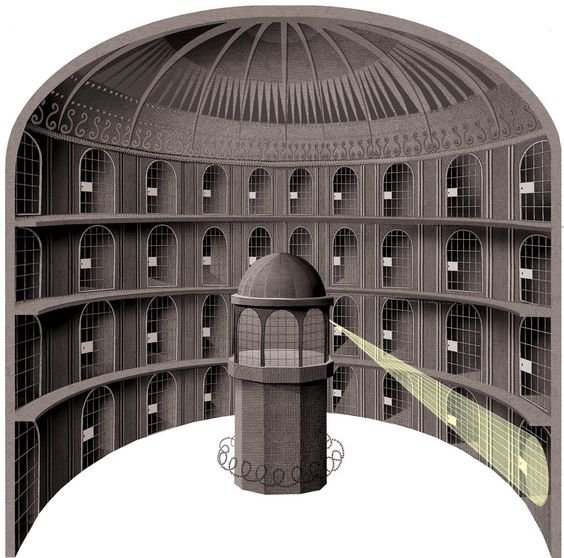

Both the Mills and the Austins belonged to the insular cult of personality that Jeremy Bentham wove around himself. Bentham, famous for his trade-friendly Utilitarian philosophy, his defense of pederasty, and his “panopticon” prison scheme, preferred to surround himself with young married couples who inverted gender roles. Lucie Austin’s parents fit this description, her mother being an aggressive, swarthy, mustachioed lady, her father a weak-willed invalid. When Lucie took a husband of her own (Cosmo’s uncle Alexander), the dynamic was more traditional, but Alexander, true to fashionable Reform-type politics, gave Lucie control over her own earnings and assisted her literary career.

A plan of Jeremy Bentham’s “panopticon” prison design.

Although from an ennobled Scottish Family, Alexander Duff Gordon was not independently wealthy. Lucie supplemented their income through her relationship with her mother’s employer John Murray III, who had built his grandfather’s publishing enterprise into a pillar of the Empire. Lucie made a name for herself by translating into English the type of German and French literature that would later preoccupy Sigmund Freud (from Katherine Frank’s biography “Lucie Duff Gordon: A Passage to Egypt”):

“Had Lucie, however, kept up her settled, happy, domestic, social and literary life in London, we would scarcely have heard of her, unless, while looking for something in the British Library catalogue, we were distracted by an entry for an obscure compilation of French criminal trials or a book on witchcraft in seventeenth-century Germany or some other book she translated. Or unless we came across her name in a critical introduction to one of Meredith’s novels, or paused at a footnote in John Stuart Mill’s or [Thomas] Carlyle’s letters.”

Lucie’s mother Sarah was close to Murray: she translated risqué German works for him and used the publisher’s office as her mailbox for an illicit, long-distance, and very kinky love affair with another of his authors, the reprobate Prince Hermann von Pueckler-Muskau— a man well connected at the German embassy in London and also very interested in Egyptian affairs.

Sarah was a strange mother. She went out of her way to involve the prepubescent Lucie in her weird relationship with Pueckler-Muskau; as a very young child Lucie was often left alone in the company of Bentham. By thirteen Lucie was involved in her first homosexual affair, about the same time she began to act out in the presence of her mother’s friends: her behavior was so manic that one acquaintance said “I regard her as a potential homicide”. (Freud would have probably called it ‘hysteria’.) As she grew up, Lucie developed a cameleon-like quality of transforming herself into whatever the milieu around her desired her to be, but was socially hindered by an underlying coarseness of character.

In many ways, Lucie’s life was a continuation of her mothers, and her mother’s contacts, particularly through John Stuart Mill and Murray’s circle, were the most important in Lucie’s life. Sarah’s social circle brought Lucie into contact with Heinrich Heine, Thomas Carlyle and other bohemian types; Murray sought Sarah for translations regarding Goethe. Lucie’s father, despite his invalid condition, was awarded many lucrative posts thanks to his friends among Reform politicians and the founders of University College London.

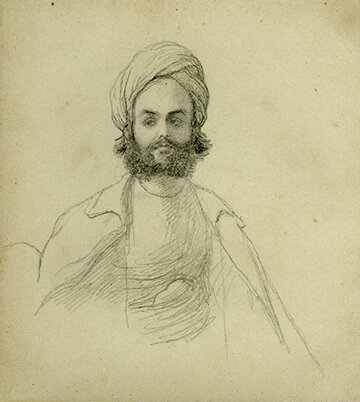

One of the most telling episodes in Lucie’s life was her relationship with an agent of an Indian potentate named Nana Sahib. This agent, the Muslim son of an Indian maidservant who was brought up and educated by British Missionaries, was called Azimullah Khan. Azimullah and Nana Sahib were responsible for the obscene Massacre at Cawnpore and ultimately the Indian Mutany of 1857, which they were able to carry out using information Azimullah collected while a guest at Lucie’s home. Through Lucie’s contacts, Azimullah was able to understand how the British were conducting the Crimean War and the agenda of Lucie’s journalist friends, who for the first time were reporting from the front lines and influencing public opinion on military strategy. The result was that the Crimean War was very unpopular. Azimullah was therefore able to gauge the limits of Britain’s response to a mutiny fermented by his Hindu master.

Strangely, Lucie’s biographer Katherine Frank fails to mention that at the time of Azimullah’s information collecting, Lucie’s surrogate brother John Stuart Mill was head of the East India Company’s intelligence apparatus. A functionary of Nana Sahib’s like Azimullah Kahn who was brought up by missionaries, employed by the British military but fired for corruption, then taken up as a right-hand man by a rebellious lord-vassal, couldn’t have sneezed without the economist knowing about it. Furthermore, Lucie bent over backwards to give Azimullah access to influential figures, introducing him as a “charming young Musselman Mahrajah, who calls me his European mother”— a brazen lie. Azimullah’s strategy was to crawl up the skirts of Lucie’s reforming friends and report home: “When Nana Sahib’s mansion was looted by the British soldiers they found bundles of letters— some of them clearly amorous— to Azimullah from various English ladies. Among these, there may have been several familiar (but not amorous) ones from Janet [Lucie’s eldest daughter] as well as a number of long, lively letters from Lucie, signed with affection in her unmistakable bold, round hand.”

Azimullah Khan, (1854/55) by Richard Doyle, uncle to Arthur Conan. Courtesy of HudsonHouseMysteries.

Lucie’s grand-daughter Lina by G. F. Watts. The pink fabric represented was the same rose kincob which cost so many hundreds of lives at Cawnpore.

Lucie never faced up to her role in this bloody business, but can she really hide behind ignorance? As a present for sheltering his agent, Nana Sahib gave the thirty-something translator a “necklace of emeralds, rubies and pearls, and a bolt of exquisite kincob cloth, woven of deep rose silk and real gold threads.” Whatever Lucie’s actual state of naivete, the British Government chose not to renew the British East India company’s charter as a result of the mutiny. John Stuart Mill was left a persona non grata, and advised not to seek employment in the new Raj government in 1858— instead he pursued literary aims, eventually contracting a young Sigmund Freud to translate some of his works into German. Why might Mill have scuppered his own intelligence career? No answer would be complete without pointing out that when British taxpayers assumed responsibility for governing India they assumed the costs of doing business there without necessarily benefiting from the profits of private trade.

The defining event of Lucie’s life happened (ostensibly) as a result of her contracting a respiratory illness; doctors told her that she must travel to a warmer climate or face death. She chose Egypt for reasons I’ve detailed earlier.

I will end this post with a comparison between Lucie and Lucy. When in Egypt, Lucie railed against abuse of power but cooperated with local big-wigs in the illicit trade in antiquities. She wrote against Ismail’s ‘slavery’ but owned a slave herself, and prided herself on treating servants as slaves. She set herself up as a witch doctor, knowingly selling placebos to uneducated locals who came to her for medical help; she also convinced these people she could see into the future and sold her services as a soothsayer. Lucy regularly enjoyed the hospitality of people who were vastly less well off than herself, hospitality offered because of lies Lucie told about herself. Lucie was callous in the face of exploitation in other ways too, encouraging her neglected son to visit prostitutes in Egypt (most likely slaves themselves) which resulted in his early death. In the words of her mother-in-law, Lucie’s world view was based on “German materialism” and never showed a hint of Christianity. In modern terms, one might call Lucie ‘narcissistic’ or ‘sociopathic’.

LDG was clearly inspired by her famous in-law, consider the following designs in light of the portraits of Lucie, Lady Mary Montagu and QE1 earlier in this post:

Advertisement in Arkansas Democrat of Little Rock, March 19th 1922.

An LDG “teagie” or tea-gown, a late afternoon garment free from restrictive supports and advertised as the type of outfit for rich married women to meet their lovers in.

Images from Ziegfeld Follies’ “Harem of the Peacocks”. The Harem motif was exhaustively exploited by Flo Ziegfeld.

Ziegfeld girl Daisy Morgan sporting the omnipresent ostrich feathers and stylized harem outfit in a promotional photograph. HoldThisPhoto

Perhaps LDG’s involvement with the exploitative Flo Ziegfeld and Alfred Cheney Johnston reflects similarities in the characters of Lucie and Lucy— perhaps when Teddy mistook LDG for her aunt he’d hit on something more insightful than either of them realized.