Islam and the Monroe Twinings

The Society of Friends came to my attention as I looked into the history of the Universalist community here in Monroe, WI. Universalists— anglophone Christians of an 1860s-abolitionist, radical protestant stripe— ran Green County’s banking industry when Monroe was the epicenter for President Lincoln’s “Bonelatta” currency-counterfeiting gang (1853-71). This gang distributed fake federal treasury bills which were printed in New York City and Philadelphia.

These “Bonelatta” criminals accounted for about 40% of our town’s population** and were affiliated with the nascent Republican (“Union”) Party, members of which held southern (slave-holding-state) investments that they stood to loose after the South’s secession. This financial reversal was acutely felt by peers of Arabut Ludlow, Green County’s banker-in-chief.

** The may be true, but the Secret Service source for the information was misquoted by Monroe’s newspapers. What we can say is many of Monroe’s economic elites were involved.

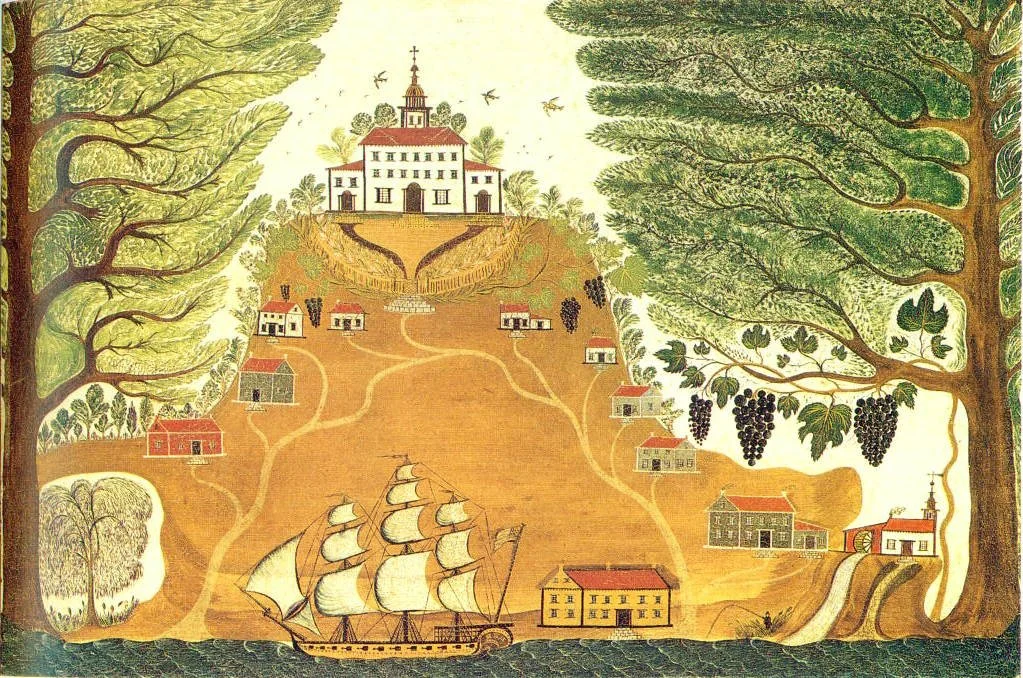

Monroe, WI’s temple of Universalism.

Our Quaker connection comes in via the Bonelatta/Universalists’ public education plan for children. Once local “community leaders” rallied powerful families around the “Universalist” banner, they sent for an East Coast Quaker to oversee their “public instruction” program— and a military Quaker at that. (Readers may wish to read about the Universalists’ 1920-era film education initiative with UW-Madison during Leon Goetz’s production of “A Romance of the Movies” starring Edith May. Edith May’s Ziegfeld Follies/Quaker connection is here.) Before I explain why they sent for this Quaker, I’ll explain what our Universalist crowd was about.

Most of Monroe’s Universalists were not Universalists prior to moving to Monroe— they were a hodge-podge of Radical Protestants from places like Vermont, or even Canada, (counterfeiting-friendly backwaters) who were united under the Universalist banner by two prominent military gentlemen, the Admiral (Nathaniel Treat) and the General (H.W. Whitney). Both men were known by their military titles. The new Admiral/General religious community looked to a prominent Hicksite Quaker military family back east, the Twinings, to lead their initiative shaping Green County’s, and indeed Wisconsin’s, public education system.

From the Milwaukee Journal of July 29th, 1928, “Where 50-Year Residents are Newcomers”:

Both (Nathaniel Treat and H. W. Whitney) were among the organizers of the Universalist church at Monroe. They, with other pioneers from New England, New York and Pennsylvania-- the Ludlows, Chadwicks, Whites, Woods, Dodges, Chandlers, Copelands, Youngs, Binghams, etc., settled in Monroe, built homes of the colonial style in which they had lived back east, and in time began to meet first in one and then another for religious services. Before emigrating they had been members of various denominations-- Universalists, Unitarian, Congregational, Episcopalian, Presbyterian-- so, to avoid conflict, their meetings in the west were not demonimational [sic] until in 1858 they organized as a Universalist congregation under the Rev. Dr. Daniel P. Livermore. [Who after brief tenure was succeeded by a Howe, Rev. Zadok H. Howe.]

The above is oversimplified— we know that the Youngs’ journey to “aristocracy” was far more torturous and that many of these “aristocrats” actually came from Vermont and lived in straightened circumstances (like Arabut Ludlow or Almira Humes). However, on balance this picture is accurate. By the 1880s the Twining family was firmly part of the list of names mentioned above. (The Twinings were quickly accepted, despite these families’ notorious clannishness, a characteristic entirely in keeping with contemporary family-based criminal networks.) What the above article obscures is that there were other regularly organized churches— including a Congregational church— which those inclined among these families would have been able to attend. The special in-home worship services were singular.

Why would these military men chose Universalism out of all the Radical Protestant denominations? Why would they choose a Hicksite Quaker soldier to spearhead their indoctrination efforts?

To me, these are fascinating questions and I think readers will find their answers equally astounding. In short, the answer to both is found in Islam’s military and psychological influences on Radical Protestantism, and Islam’s debt to Hermeticism. What Treat and Whitney were doing with their religious and pedagogical activism was a return to Radical Protestantism’s roots as a cosmopolitan work-around for challenges posed by multi-cultural imperialism and organized crime.

Universalism, like Quakerism, was a British-Civil-Wars era, but Central-European-inspired, Christian heresy which drew on old Arian (anti-Trinitarian) ideas by way of the Unitarian movement. “Unitarianism” was an elite cult from Transylvania under the Ottomans, but some form of Arianism like it got going wherever the Ottomans butted up against the Hapsburgs.

In Cromwell’s England, Radical Protestant sects like their indigenous branch of Unitarianism, Universalism and Quakerism were developing when a glut of Arabic literature on the history of Islam reached European collectors. This glut was caused by the Ottoman’s 1634 defeat in Poland. Prior to 1634 copies of the Koran and Islamic “medical” (really, magical hermetic works) were in European collections, but the defeat of the Ottomans by the Poles opened Islamic society in a way it had not been before.

What books suddenly became easy for Europeans to buy? Editions of the Koran would have been among the 1634 manuscripts for sale, yes, but equally important would have been histories like “History of the Prophets and Kings” or “Tarikh al-Tabari” by Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari (838–923 A.D.), which deals extensively with slave armies and slave revolts and how these shaped Islamic empires and militaries. These slave armies were the core of Muslim empires since the Abbasid Caliphate (750-861+ A.D.) which succeeded Mohammed from Mecca’s territorial expansion, i.e. from the earliest days of Islam.

Beyond their religious utility, these Abbasid slave armies had a social control function inside the Muslim world itself. The Abbasid imperial family used these ethnically-alien Turkic and Persian slaves to ‘level out’ social hierarchies and destroy their rivals for power: the Arab Penninsula’s aristocracy. These Arabian aristocrats, like aristocracies of 16th- early 17th century Europe, controlled their empire’s military as a network of peers. The Abbasids, for their short remaining time in power, were the first “Absolutists” in the manner that post-1600 A.D. European imperial/would-be imperial dynasties sought to be.

The Abbasid slave-soldier institution was designed to prevent these slaves from becoming a new aristocracy: they were to be trained to expect little in the way of compensation and very slow promotion. Slave soldiers would not create dynasties nor family protection networks of their own: their breeding, and with whom they could interact more generally, was highly regulated. The slave-soldiers’ motivation was based on their education: they would be driven by their zealotry for Allah and by their loyalty to their owner, by whose grace and at whose will alone they were spared the trials of most other Ottoman slaves. The first “modern army” was a truly dystopian institution.

Samara, the ancient city in Iraq, was founded by the Abbasids to keep their slave armies cut off from the mainstream of Islamic society, particularly aristocratic strongholds including Baghdad. There were strict rules about who these exalted slaves could marry, who could work for them, and who their children should associate with. A sort of “DC Beltline” for the early Islamic world!

Of even more contemporary interest to Europeans than Tabari would have been texts like the Chronicle of Uruj and the “Ashiqpashazade” manuscript, which are 1460-90 accounts of recent Ottoman history up to the 1420s. [See “Origin of the Janissaries” by Palmer.] Tabari’s writings, as well as the writing represented in the Uruj and the Ashiqpashazade manuscripts, were hugely influential and many Arabic-speaking writers copied, adapted or incorporated them into their own works. Islamic scholars were preoccupied with examining the “success of their [Islamic] Wars; and the greatness of their Empires” as Thomas Ross put it in his 1649 The Alcoran of Muhammad. This was not just an ancient preoccupation either as modern Islam, like many flavors of Protestantism, puts emphasis on success in the material world and temporal power as evidence of God’s favor. (See Nigosian, Islam: Its History…., Introduction.)

European intelligencers and policymakers were no less interested in these imperialist and military histories because they deal with the foundation and motivation for the formidable Janissaries: the slave-soldiers indoctrinated since childhood to spread jihad. This “new”* [1380s-1420s] development in military psychology— which first exploited kidnapped children from Ipsala, right on the modern Greek border with Turkey— just happened to coincide with the beginning of the Hussite uprisings in Bohemia. The Hussite religious/social conflicts were the Ottoman’s most likely “in” to Hapsburg lands and also birthed Protestantism.

Europe suffered under the Janissaries long before the history of this ‘modern’-style standing army was widely understood. A 16th century depiction of a Janissary soldier by a European artist. “Agha of the Janissaries and a Bölük of the Janissaries by Lambert Wyts, 1573”

The soil was prepared for Protestantism by 1420, when Hapsburg (Catholic) aggression and disregard for traditional power-sharing structures among the Kings of Bohemia precipitated the Hussite Wars, the immediate cause of which was the persecution of religious reformer (proto-Protestant) Jan Hus. These wars also gave Hussite aristocrats the opportunity to seize lucrative Catholic Church assets, which poured fuel on the protestant fire. In fact, the Taborite Hussites were at times as zealous in their banditry as Muhammad’s crowd of partisans in Medina (See Islam, Its History, Teachings and Practices, by S.A. Nigosian).

Hussite Uprisings on Europe’s Eastern Borders: The red mass is the location of Bohemian Crown Lands inside the Holy Roman Empire circa 1620. This area is the birthplace of Protestantism, and also ground zero for those aristocratic/absolutist conflicts which opened Europe up to Islamic aggression.

The Ottomans noticed that Protestantism was the Achilles’ Heel of their Catholic rivals. By 1528 in places like the Kingdom of Hungary, Protestant rulers and nobility were propped up by the Islamic slave armies mentioned earlier. From these puppet-states, Protestant ideas spread to other areas in modern-day Czechoslovakia, Poland and Germany where they were warmly received by discontented academics, striving tradespeople and princes who chaffed under Catholic emperors or papal competition. Since the time of Queen Elizabeth I at least, British (Protestant) intelligence-gatherers were deeply invested in following these Central European trends and bringing the new ideas home for policymakers.

Much like post-1670s Jewish anxieties about Sabbateans, Catholic Western Europeans saw the “Unitarian” movement in political terms, as described by Unitarian minister Susan Ritchie:

The ultimate concern about Unitarians was more than a concern with heresy; the ultimate worry was also political, with many Europeans fearing that Islamic-happy Unitarians might possibly sympathize with Ottoman ambitions, a concern that had more than an element of truth. [The Islamic Ottoman Influence on the Development of Religious Toleration in Reformation Transylvania , Seasons Journal, vol. 3, pp. 59–70.]

This map of 1190s Europe shows the Kingdom of Hungary and Transylvania in relationship to “Byzantium”, which by the 1500s was part of the Ottoman Empire.

A depiction of part of the Austro-Hungarian empire in 1910. The red territories are “Bohemian Crownlands” that would have been part of the 1620 entity pictured above. Hungary and Translyvania are part of the green “16” landmass. Ottoman territories lay to their south.

While these Islam-inspired religious reform and military ideas were in Europe before the 1630s, they were available to far fewer people and only through the prism of aristocratic international-trade monopolists or foreign service intelligence agents who had access to Muslim lands or delegates via their business activities. It took the “progress” of the Early Modern period, and the greed of hermetic (Medici) and Radical Protestant potentates to undo 700 years of successful anti-slavery activism from Christian and secular forces in Europe. (This activism started under Charlemagne, see Origins of the European Economy by Michael McCormick.)

It was under the Unitarian King John Sigismund in Hungary, who was supported by the Ottomans, that Hungary first became ground zero for the modern White Slave Trade, whereby women and children were sold for “domestic service” and prostitution in the Ottoman Empire and other parts of Africa. As Julius Kemény describes it in his Hungara: ungarische mädchen auf dem Markte (1903):

The girl trade [White Slave trade] is of far older in origin, it dates from the unholy Turkish times [1541 to 1686]. The Turkish rule in Hungary lasted for a century and a half, for a century and a half the Turkish standard with the three horse tails fluttered from the battlements of the Ofner fortress. And during this whole time the Turks were not content with devastating the country, scorching and plundering, no, they robbed the Hungarian virgins in droves and dragged them into the harem of the Pasha von Ofen or into the Istanbul seraglios of powerful Turks. And if in this long period of time a short armistice occurred here and there, then the Pasha von Ofen had his agents buy the beautiful daughters of beggarly Christians for money, and sent the most beautiful of them to the sultan and other grandees in Istanbul to curry favor. Following the Sultan’s and his great dignitaries’ taste for these “Madzsarlis” as the Hungarians called them, the desire for them in Istanbul grew stronger and stronger, and since “consumption” rose steadily, the pashas in Hungary had to pay high prices and work hard to find enough Madzsarlis to always supply Istanbul with “fresh goods”. This was done by Jewish and Armenian traders who, under the protection of the Pasha von Ofen, organized a regular trade in girls and through the same achieved wealth and reputation. There are still highly respected Armenian families in Hungary, whose ancestors laid the foundation for the current splendor and prestige of their house through the lucrative girl trade!

[Read about Florenz Ziegfeld’s industrial-scale commodification of American women/girls here; and about the exploitation of our local ‘Ziegfeld Girl’ Edith May here.]

Of course, when one is willing to sell one’s own people, it’s a very short step to selling other Europeans, as blogger Philip Jenkins summarizes:

But the danger [of kidnapping for slavery] extended far beyond Central Europe, and afflicted Mediterranean lands. Many of the worst perpetrators were themselves Europeans, ex-Christians who converted to Islam to take advantage of the rich opportunities in piracy and slaving. From the Spanish word for these “deniers” of their faith, we get the word “renegades.”

Trading in Christian slaves was a major economic focus in Eastern Europe, with the Tatar Khanate of Crimea as the major perpetrators. The Crimean Tatars were another vassal of the Ottomans, and they ranged far across the Danube lands, Poland-Lithuania, and Muscovy, reaching as far as the Baltic. They supplied legions of slaves to the notorious markets surrounding the Black Sea, from where captives might find their way anywhere across south-eastern Europe, Persia, or the Middle East.

Nor were Christians safe in the distant Atlantic periphery. From Algiers, Tunis, Tripoli, and other centers, Barbary pirates regularly raided the coasts of Britain, France, and Ireland. In 1627, they seized eight hundred people from the coasts of Iceland. Only a handful of those victims ever returned home.

Through these centuries, many European nations and sub-national groups pursued war, violence and raiding, which was absolutely not the prerogative of any one side, or any religion. Yet military power gave a decisive advantage to Islamic forces, who seemed able to strike anywhere. Historian Robert Davis credibly estimates that the Barbary lands alone might have taken over a million Christian slaves between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries.

When Davis’s figures were first published, some historians argued that they were modest when set aside the numbers for the African trade to the Americas in the same period, which reliably estimates twelve million carried across the Atlantic. So, they protested, the European situation was barely one-twelfth that of the African trade. That response, though, is misleading, because the Barbary trade was only one component of a much larger European picture. In particular, it takes no account of the very large and quite distinct activities of the Crimean Tatars, and some of their slaving attacks claimed tens of thousands of Christian victims in single sweeps.

What Jenkins leaves out is that it was groups who existed on the periphery of Europe, like Jews, Armenians and Greeks who benefited from the policies of powerful men like John Sigismund, and there were more like him as Radical Protestantism spread in Northern Europe and Hermeticism spread in Catholic lands. Where this poison had not corrupted government in Christian Europe, such slaving was acknowledged as state-sponsored organized crime. Unitarianism was adopted in plutocracies precisely to put a “Christian” face on this Islamic state of affairs.

Present-day historians are comfortable with the idea that English Radical Protestantism drew life from European Unitarianism and the Hussite experience, but that the radicals drew upon Islam and the tsunami of military-psychological literature that flowed westward with the Koran is a touchy subject. That part of the cultural exchange is hardly mentioned. When these psychological ideas are acknowledged at all, they are stripped of military significance, balled up into the idea of “Islamic Science” and lauded as a contribution to the “enlightenment” in Europe. Such a conception of “Islamic Science” conflates magical hermetic speculation with the scientific method— a fallacy promoted by the Warburg international banking family last century. Serious historians are moving away from this conception, but you’ll still hear it from people evangelizing for Islam, assorted mystery cults, or Unitarian Universalism. Where Islam has made a serious, if not positive, contribution to Western development is in military psychology.

And this Islamic contribution could not have come at a better time for Oliver Cromwell. Less than a decade after the Turks lost to the Poles in 1634, Cromwell’s army was losing badly to his Monarchist rivals. Military historian Mark Cartwright summarizes Cromwell’s dilemma:

Defeat at Roundway Down in July 1643 saw the near-destruction of the Parliamentary army of the Western Association (several southwest counties) led by Sir William Waller (1597-1668). One of the problems for the Parliamentarians was that their best force, the London regiments, were not available for lengthy service since their absence from the capital severely impacted commercial activity…

These setbacks again led to a Parliamentarian discussion on how to form a permanent and more professional army, a move called for by Oliver Cromwell in December 1644, a country gentleman and a visionary military leader. What was needed was a standing army that could take the field wherever their commanders thought best and for however long it took to gain victory, a significant consideration given that the war involved many lengthy sieges. Another weakness had been the competition between the various Association armies and the absence of any overarching hierarchy of command...

A significant development in England’s army was Parliament’s decision, effective from April 1645, to forbid any of its members from also being a military commander. The effect of the Self-Denying Ordinance was to remove any commanders who were politically powerful but had no military competence. Not only were the troops now professionals but also the senior officers. Sir William Waller was amongst the casualties of those who had to give up their commands. The first overall commander of the New Model Army was Sir Thomas Fairfax, a man of talent and experience.

What Cromwell needed was an army whose members had no political agency outside of what derived from their overlord— or later “Lord Protector”— a dilemma to which the Abbasid Caliphate would have related.

Thinking contemporaries of Oliver Cromwell and George Fox (founder of Quakerism) were quick to understand Islam’s unique contribution to the Parliamentarian cause. Royalist commentators, a highly educated segment of the population, saw the parallels between Ottoman history (Islam) and what Cromwell and his confederates were doing (Radical Protestantism paired with military reform). Thomas Ross’s 1649 translation of the Koran was impeded by Cromwell because it reflected badly on Cromwell’s government. Cromwell understood the political danger inherent in embracing his Islamic inspiration. Ross summarizes Cromwell’s position nicely:

(Christian Reader) though some, conscious of their own instability in Religion, and of theirs (too like Turks in this) whose prosperity and opinions they follow, were unwilling this [translation of the Koran] should see the Press, yet am I confident, if thou hast been so true a votary to orthodox Religion, as to keep thy self untainted of their follies, this shall not hurt thee: And as for those of that Batch, having once abandoned the Sun of the Gospel, I believe they will wander as far into utter darkness, by following strange lights, as by this Ignis Fatuus [a fairy, a will-o'-the-wisp or something deceptive or deluding] of the Alcoran. Such as it is, I present to thee, having taken the pains only to translate it out of French, not doubting, though it hath been a poyson, that hath infected a very great, but most unsound part of the Universe, it may prove an Antidote, to confirm in thee the health of Christianity.

[I’ve highlighted the “strange lights” segment because that has a wacky connection to the Twinings which I’ll explain at the end of the post. If you’re curious about how Cromwell attracted a vulgar “Batch” of people, please see my post When Quakers Ran the Sex Trade.]

What Ross, and the French-Ottoman merchant André de Ryer whose 1647 French translation of the Koran Ross worked from, understood about Muhammad was the military prowess of his reinterpretation of Arianism and Judaism. As summarized by historian John Tolan in “Mohammad: Republican Revolutionary”:

But what interests Ross most is Mahomet’s project of political revolution under the guise of religious reform. Not content to be a prophet, he says, Mahomet schemes to become king. To this effect, he pandered to their basest instincts by permitting polygamy and by promising a heavenly abode replete with sensual delights. Thus, says Ross, Mahomet managed to attract ‘a numerous, though vulgar party of the people’. Just like Cromwell, Ross may be tempted to say (but of course does not). That the parliamentarians are the object of this portrait of Mahomet becomes even clearer in what follows. He had ‘under pretence of Reformation of Religion, gained many followers’; now ‘he resolved to yoak to it that other concomitant in popular disturbances, liberty, proclaiming it to be the will of God’. English revolutionaries invoked religious reformation (greater tolerance and the curbing the wealth and influence of the Anglican Church) and asserted the liberty of the English people to their self-government. Mahomet does the same: he frees his slave Zeidi in the name of universal liberty.

Of course, Mohammad enslaved many thousands more people than he ever freed, and his followers certainly did not have anything like self-government (even in modern-day Saudi Arabia). But frankly, modern European notions about “self-government” wouldn’t have mattered to Muhammad’s contemporary followers: they looked for power and wealth. Ironically, these were exactly the things of which the Abbasid stripped Muhammad’s Peninsula Aristocracy. History shows us that for Cromwell, for Muhammad, or even for L. Ron Hubbard, the cheerful stuff is only window-dressing along the way to power.

The idea of pairing revolutionary politics with military and religious reform that Tolan recognizes in Ross’s criticism is completely within the present-day, mainstream understanding of Cromwell’s political program as long as the Islamic dimension is omitted. For example, take this description of how the Leveller movement, a political movement with which Oliver Cromwell collaborated, wished to achieve political power on par with British aristocrats:

In many ways, the Levellers embodied a populist movement and exercised further control and influence through a well-thought out propaganda mechanism which involved pamphlets, petitions and speeches, all of which connected the group with the general public and conveyed their message… they campaigned for a new political landscape which would emphasize freedom and inclusiveness, principles which would many years later be adopted by the revolutionaries of France and later America.

Despite modern pundits’ neglect of Islam’s contribution to religiously-based militarism and political radicalism, Cromwell did adopt these Islamic military ideas in order to create his New Model Army, to which Quakers acted as an (expendable) pamphlet-propaganda wing. As publishing historian Brooke Palmieri writes:

It made sense for the Quakers to cultivate an exaggerated presence in order to make their voices heard among the clamor of other religious sects formed after English Civil War. But what set them apart was the volume of their printed works. During the early years of their establishment in the 1650s, Quakers published about a pamphlet a week, paid for through a collectively managed fund, and distributed by a network of itinerant preachers known as the “Valiant Sixty.” The Sixty, which were in fact more than sixty people, included George Fox, Margaret Fell Fox, Mary Fisher, and sixteen-year-old George Whitehead. Because they commanded others to tremble before the Lord, they were called Quakers, a title they re-appropriated from their critics…

Even though the tone of early Quaker pamphlets was mostly apocalyptic, the system of pamphlet production and distribution the Valiant Sixty built was ultimately stronger than some of the beliefs it spread. Consumers of these publications included converts across England who had been visited at one time or another by members of the Valiant Sixty.

[note] In the first three decades of Quakerism, Quaker pamphlets took up between 8.8 and 10 percent of all known titles published in England— no small feat for a group that was about 0.73% of the population. O’Malley, Thomas. “‘Defying the Powers and Tempering the Spirit.’ A Review of Quaker Control over their Publications 1672-1689.” Journal of Ecclesiastical History 33 (January 1982) 72-88.

Palmieri goes on to note that this pamphlet distribution system morphed into a centrally-controlled network where influential Quakers censored subordinate Quakers’ writings and monitored their critics:

Over the years, the Quaker publication process grew both more refined and more practical, helping to translate the mystical core of Quakerism into a set of tools for effective collective action. On 15 September 1673, the Quakers founded the Second Morning Meeting to undertake the task of reviewing manuscript submissions for publication, but also to maintain a library, agreeing:

“That 2 of a sort of all bookes written by frends be procured & kept together & for the time to come that the bookseller bring in 2 of a sort likewise of all bookes that are printed, that if any book be perverted by our Adversaryes we may know where to find it. And that there be gotten one of a sort of every book that has been written against the Truth from the beginning.”

By “mystical” Palmieri means Hermetic, and an excellent explanation of Hermeticism’s deep influence on Quakerism can be found in The Refiner’s Fire by Brooke. Right now, however, I’d like to talk about Islam’s influence on George Fox’s thinking, as Pelmeiri alluded to with her phrase “they were called Quakers, a title they re-appropriated from their critics”.

George Fox went to prison in Derby in 1650 for blasphemous preaching, especially to groups of Parliamentarian soldiers, and preaching in a way that encouraged disorder. These soldiers would “fly like chaff” before Fox’s message, he tells us. The judge who sentenced Fox, Justice Gervase Bennet, noted how Fox encouraged people to “quake” in response to his teaching. According to Fox’s 19th century editor Rufus M. Jones , this “quaking” was a reference to widely-discussed practices among Islamic religious refugees in England at the time:

This is the whole of our data for the origin of the name “Quaker.” Fox told the Justice to tremble at the word of the Lord, and the Justice thereupon fixed the name “quaker” upon him. There is probably, however, something back of this particular incident which helped give the name significance. The editors of the New English Dictionary (see the word Quaker) have discovered the fact that this name for a religious sect was not entirely new at this time. Letter No. 2,624 of the Clarendon collection, written in 1647, speaks of a sect from the continent possessed of a remarkable capacity for trembling or quaking: “I heare of a sect of woemen (they are at Southworke[a London borough on the Thames]) come from beyond the Sea, called quakers, and these swell, shiver and shake, and when they come to themselves (for in all this fitt Mahomett’s holy-ghost hath bin conversing with them) they begin to preach what hath been delivered to them by the Spirit.” It seems probable that Justice Bennet merely employed a term of reproach already familiar. It is, further, evident that the Friends themselves were sometimes given to trembling, and that the name came into general use because it fitted. (See Sewel’s “History of the People Called Quakers,” Vol. I., p. 63. Philadelphia, 1823.) The name first appears in the records of Parliament, in the Journals of the House of Commons, in 1654.

Who these Muslim women were and why they were allowed to either travel without men, or to be the face of their cult rather than their men, is a question I hope to answer later. [Their practices sound like something from the Sufi (Hermetical!) tradition.] Whatever their story is, Fox’s appropriation of their channeling in his missionary work to soldiers got the attention of Cromwell’s military agents, who were very interested in soldier-focused radical belief systems and protecting these systems from suppression by Presbyterians.

During Fox’s time in jail, he relates how agents of Cromwell’s government came to him and offered him release from prison if he’d be chaplain to newly enlisted New Model Army soldiers… which of course Fox, writing in 1690 after the Restoration of the Monarchy, says he refused to do. We know however, that Cromwell valued Fox’s advice on certain things, including nixing the foundation of a Radical Protestant university to challenge the Royalists at Oxford [Sylvia Brown, Early Quakers and the Use of Latin, 1655-1700 in Acta Conventus Neo-Latini vol 16]. Cromwell and his military commander Fairfax repeatedly came to the aid of politically troublesome Quakers and Universalists when their agitation ran afoul of Presbyterians. Quakers did not declare their pacifism until after the failure of the Fifth Monarchist Uprising, when the king was back in power.

While Quakers had their role to play in Cromwell’s print-media propaganda efforts, it was Universalism which came closest to being the “Islam” of the New Model Army. As I stated previously, “Universalism” is one of the flavors of Radical Protestantism that took root in London during the English Civil Wars; Universalism was intimately connected with the “Leveller” military-political movement through the person of its co-founder Gerrard Winstanley, who was both a Quaker and a Universalist. The basic idea of Universalism is that God will eventually save everyone, i.e. you can do really bad things and still be saved.

Gerard Winstanley, hands struggling with a tumble of new ideas.

It was the Leveller movement within the New Model Army which allowed it to coallesce into a political force in itself and propel Cromwell to his dictatorship:

With support from the Scots, the Presbyterian faction called for the disbandment of the New Model Army and for a settlement with the King. Meanwhile, during 1647, the Army began to emerge as a political force in its own right, promoting a programme of constitutional reforms inspired by the Levellers. The Independents [“a loose coalition of religious and political radicals”] remained closely allied to the Army radicals and also retained the support of St John's Middle Group, which continued to press for a negotiated settlement but was not prepared to submit to the King's stubborn intransigence in negotiations. In July 1647, a number of leading Independent MPs were forced to flee to the Army when Presbyterian militants threatened to seize control of London. The Independents were restored to power when the Army marched into the city in August 1647.

These Independents were a group of men that included Sir Henry Vane, who would become associated with the American Colonies and the religious ferment there:

The Independent faction was a loose coalition of political and religious radicals. It included a small number of republicans associated with Henry Marten and the would-be political reformers later known as "Commonwealthsmen", who included Sir Arthur Hesilrige and Edmund Ludlow. The most prominent of the religious zealots was Sir Henry Vane. Religious radicals, including the future Fifth Monarchists John Carew and Colonel Harrison, bolstered support for the Independents when they were elected to Parliament in the "recruiter" by-elections of the mid-1640s. The religious Independents advocated freedom of religion for non-Catholics and the complete separation of church and state.

While Cromwell never picked a ‘brand’ of Radical Protestantism for himself, he was a friend to non-conformist thinkers, like the Unitarian John Biddle and even helped George Fox’s most radical lieutenant James Naylor to the extent it was safe for both Cromwell (and Fox) to do so. Naylor had at one time been a member of the New Model Army and its commander, General Fairfax, was at the forefront alongside Cromwell in pushing for “toleration” of Radical Protestant dissenters. Of course “toleration” would be the watch-word of Radical Protestants after the Restoration, when they were attempting to limit their losses.

‘Limiting their losses’ became the modus oprendi of Radical Protestants after the failure of the Fifth Monarchist Uprising. After this defeat, the Quakers decided to embrace pacifism and became spies/agent provocateurs for the king in politically-unreliable slave-holding colonies. Henry Stubbe (a good friend of the that aforementioned Henry Vane who worked at Oxford’s Bodlien Library where a large collection of the Arabic scripts described above were stored) even latched onto Muhammad’s Koran as a symbol of “toleration” while lobbying for “toleration” of the religious radicals who had previously thrown their lot in with Cromwell.

[After the failure of the Fifth Monarchists, many dissident Protestants, including Quakers, became heavily involved in the Atlantic Trade, including Africa-sourced slavery, which blossomed during Cromwell’s time in power because of his “Grand Design” in the New World. See also B. Coulton’s paper “Cromwell and the Readmission of the Jews”. Previously this international trade in Black slaves had been the specialty of the Muslim world; intra-Africa trade and enslavement had for time immemorial been dominated by other Black Africans, usually from coastal kingdoms.]

It was also during this time of limiting losses that the Quakers abandoned Fox’s anti-intellectualism and developed a keen interest in education, particularly that of children. This was a very wise policy from both the Hermetic (Symposium, Plato) and Islamic (Janissary) historical perspective. From the website of NYC’s “Friends Seminary”:

Quakers first established schools in England to provide their children with a "guarded" education, one that protected the children from the influences of the larger society. When Friends arrived in America, they immediately founded schools to educate both boys and girls. Friends schools were founded in Philadelphia in the late 1600s. Believing that spiritual, social, and intellectual growth are closely linked, Friends have always stressed the importance of an education that supports the overall development of the child.

The Twining family drew on this Quaker heritage in order to bring their concept, and their Universalist sponsors’ concept, of the “overall development of the child” to Green County, WI. But what about the family’s military emphasis? The Twining’s re-adoption of the military lifestyle was a product of the American Revolutionary War.

By the late 1770s, Quakers had for nearly one hundred years professed to be pacifists (while making lucrative war loans and investing in the proceeds of war). They’d achieved a measure of influence with the British Monarchy and controlled the Pennsylvania colony. Quaker landholdings were largely insulated from depredations by the Livingston’s Indian allies; Quakers could usually rely on somebody else (particularly the British military) to keep them safe and were consequently opposed to paying more taxes for military preparedness.

That’s the typical mid-18th century Quaker stance. There were however a small nucleus of very wealthy Quakers in Philadelphia who understood how valuable war profiteering could be— they only needed to look at William Penn’s family for an example. War was certainly in the air and these pro-military-spending Friends had the luxury of deciding who would be their allies and who their enemies. Benjamin Franklin was closely associated with this pro-war camp and his toing-and-froing from France and other countries was in service of their goals. The Twining family shared values with this influential Quaker minority and were themselves achieving military distinction by 1812.

Commander Nathan Crook Twining Sr. around 1913, when things were heating up for both Pancho Villa and German-sponsored movie men in Chicago. While the Twinings came to Monroe as “Congregationalists” (History of Green County, 1884), by 1895 a Universalist Church wedding was conducted in their family home. (Monroe Evening Times, July 19th 1895.)

The Twinings were more than just Quakers-who-Followed-the-Money, however. They were Hicksite Quakers. These were Quakers who adopted elements of Unitarianism (Arianism) and wanted to bring Quakerism back to it’s “mystical” roots, which were inspired by the Hermetic writings that the Medici brought over from the Islamic world and paid Marsilio Ficino to translate into Latin. Preeminent among these writings is the "Pymander” text, a text which offers a different version of the biblical Genesis story, wherein it is claimed that individuals can re-achieve godhood by certain secret knowledge: the “Inner Light” of the Quakers. The reintroduction of mystery-cult psychology into the Christian West is another honest contribution of the Islamic world to the European “Renaissance” and “Enlightenment”. An excellent examination of how the ideas in Pymander influenced Quaker and Mormon beliefs can be found in the first chapter of Brooke’s’ The Refiners’ Fire.

This is an image of a 14th century Arabic version of the Hermetical (Ancient Greek) Cyranides. Magical medicine— and I do mean magical, in no way scientific— was a mainstay of the Islamic world and underlay the quakery of European “Court Physicians” or Pietist medicine producers who subscribed to “Renaissance Hermeticism”. The magic usually involves some form of borrowing/stealing divine power to work healing/death, deception or psychological enslavement.

The Twinings were Hicksite Quakers from before “Prof.” N. C. Twining left New Jersey (the fiefdom of the Livingstons) for Green County to oversee the foundation of the county’s school system (and eventually teacher training colleges). Although the Twinings seem to have adopted Universalist/Unitarian beliefs by the 1890s, when they originally came they were part of Rev. Miner'’s Congregationalist flock. Readers will remember that Rev. Miner didn’t stick to Congregationalism long after relocating to Monroe— after just two years he got into trade and abandoned his religious calling.

[In my posts on the Miner and Young Families, as well as the Kirtland Banking Scandal, I make the argument that Rev. Miner’s family was involved in the Mormon financial schemes.]

Label by Kundert, Dorothy Dietz (1904-1992), “Churchill School,” Monroe Public Library Kundert Special Collections, accessed November 1, 2022, http://www.mplspecialcollections.org/document/SCHOOLBUILDINGS00023. Prof. Nathaniel Crook Twining was particularly busy establishing the High School and served as “principal” of the Churchill School.

The Churchill School, where Prof. Twining was principal in the 1880s, was located in that tony part of town where the Universalist Church, Ludlow’s Bank, Daniel Young’s Grocery, Dunwiddie law offices, most of the nice hotels and the Goetz tailor shop were located. Almira’s “whiskey hotel” was six blocks west of the school on what is today the same street (9th converges into 8th street today). The Ludow and Bingham family homes (at least the flagship ones) were a couple blocks north.

I’ve noticed in my studies of WWI-era Monroe that the Universalist faction liked to use our local school administrators and teachers to do their political dirty work, for instance, Paul F. Neverman, the highschool superintendent in 1913, was a “capo” in Ludlow’s political persecution of our county’s judge, John M. Becker. (Their Dunwiddie men had by this time left that office.) The schools were also used as recruiting depots. Please consider the images below:

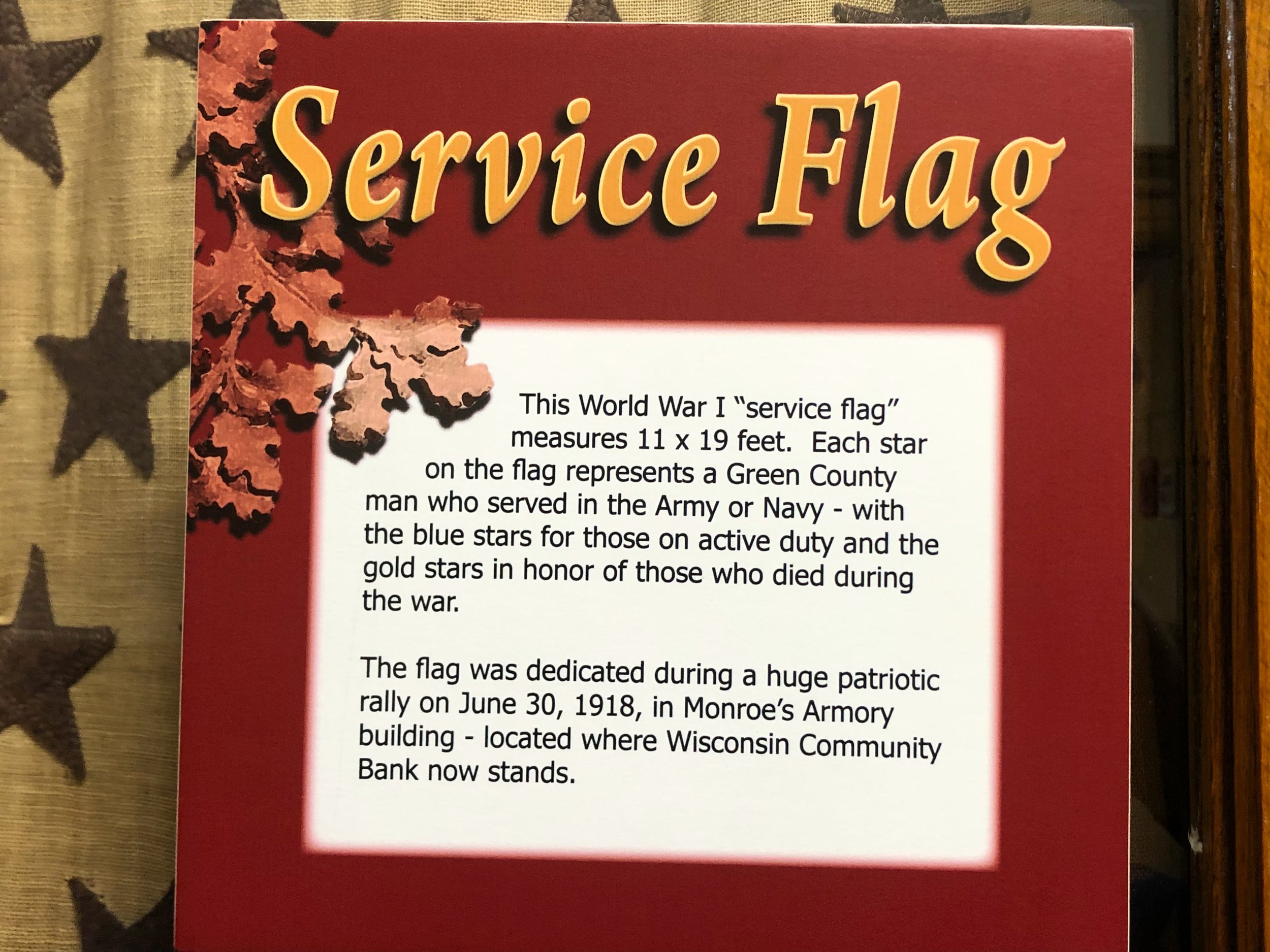

The “Service Flag” displayed in our Historic Courthouse on the Square in central Monroe, WI.

There are about 420 stars on that flag. 420 men (teens) from Green County (population, several thousand) volunteered to fight in a war that 90% of their parents had just voted to stay out of. (Judge Becker organized the only plebiscite on joining WWI held in the United States of America.) According to Hamilton’s 1976 The Story of Monroe, there was a lusty feeling of war-enthusiasm among the young men who signed up, and great disappointment when they never saw action. Of course, this sort of ignorance is only to be expected given that Superintendent Neverman stumped war bonds from his classroom. I interpret this flag as evidence that the Twinings successfully nurtured the next generation of ‘jihadists’.

That the Twinings were seekers for new Radical Protestant denominations is in keeping with the ruptures experienced by East Coast Quakers after they lost Imperial British patronage and their raison d’etre. By the 1820s the Hicksite Schism had rent their world, over the next 50 years the Quaker faith would hemorrhage followers into other assorted Protestant groups. Rich “orthodox” Quakers tended to convert to Episcopalianism in Philadelphia (where they declared themselves “the conscience of the nation”! See Church and Estate, Rzeznik) while the more radical Hicksites tended toward things like Universalism, Unitarianism and even Mormonism.

While it’s easy to change what we call ourselves, changing our underlying beliefs is surprisingly difficult. Prof. Twining may have called himself a Congregationalist, then a Universalist, but his pastimes show he was very much still an Hermeticist at heart: he started up his own mystery cult here in Monroe!

Twining’s organization was a “secret order”-cum-insurance-outfit that was originally founded in Massachusetts, called “The Royal Arcanum”. Prof. Twining styled it as an organization for men of “broad culture and wide experience”; the name itself suggests Freemasonry, which had suffered a catastrophic loss of prestige roughly 40 years earlier with the 1826 murder of William Morgan back in New England. Freemasonry’s “period in the wilderness” corresponds to a similar loss of prestige for the USA’s privileged Quaker community and a remarkable lacuna in scholarship of the Society of Friend’s history (1820-40).

Seal of the Royal Arcanum

Medals awarded by the Royal Arcanum, courtesy of PheonixMasonry.org.

The Royal Arcanum’s Boston, MA headquarters.

The Anti-Masonry political movement in the United States over the 1830s-40s was a grass roots movement aimed at rooting out the Freemasonry-based corruption institutionalized in policing, judicial and political bodies throughout the United States. In many places it was impossible to get a fair trail or police services without having Masonic protection. Naturally, modern pundits usually paint Anti-Masonry in terms of ‘irrational bigotry’ or other such nonsense. Prof. Twining himself was more than happy to return to the bad old days, as were his Universalist patrons.

Conclusion: When Monroe’s military elite gathered the Bonelatta profiteers into their religious fold, they chose the old “Islam” of the New Model Army, Universalism, as their banner. They chose an hermetically-influenced Quaker schismatic allied to Philadelphia’s military-industrial complex to indoctrinate the next generation of jihadists for Roosevelt’s Cuban conflict, WWI and WWII. Sadly, Green County’s public schools would be used as recruiting depots well into the FDR administration.

Personally, I find the history of the Monroe Twinings fascinating as they relate so many world-wide events to our local history, ‘facts-on-the-ground’ so to speak, and offer insights into the behind-the-scenes workings of the US Government over a formative period. If you’d like to read about Ludlow persecution of anti-war activists, please see my posts Persecuting Judge Becker and the Ludlow’s Civil War-era political oppression in Monroe.

The Twining family itself enjoyed tremendous success in the US military between the 1890s and 1960s. Prof. Twining’s nephew Nathan Farragut Twining, an Air Force member, became chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff between 1957-60. He oversaw the UFO “Project Bluebook” investigation, which was designed to downplay sightings of “strange lights” in the sky and, more importantly, the troubling psychological/spiritual phenomenon associated with these experiences. His brother Merrill became a Marine Corps general and the family enjoyed a handful of other men in influential positions. As a dynasty, they appear to have petered out by the late 1960s.

Prior to the 1940s, when somebody saw a UFO or met an “alien”, these experiences fell under the expertise of psychologists or demonologists. (Though psychologists could do little to help!)

During WWII pilots like Roald Dahl (above) began to see “foo fighters”, the original “UFOs”. (Dahl was also an illegal British espionage agent in D.C. who interfered with our domestic politics.) The US military was quick to claim authority over these experiences, just like they claimed ownership of Dahl’s/Disney’s “gremlin” characters, which were clearly inspired by the foo fighter phenomenon. Shepherding belief about UFOs, aka modern demonology, has been a military preoccupation ever since.

Where are the Universalists today? The fundamental similarity between Universalism and Unitarianism was openly acknowledged by the sects in 1961, when they threw their lots in together under the banner of humanism, not Christianity. From the Unitarian Universalist Association website:

Unitarian Universalism affirms and promotes seven Principles, grounded in the humanistic teachings of the world's religions. Our spirituality is unbounded, drawing from scripture and science, nature and philosophy, personal experience and ancient tradition as described in our six Sources.

A Unitarian Universalist Association-promoted yard sign. Radical Protestants have historically been very soft on human trafficking; profiting from slave/tenant farmer revolts; and sympathetic to the needs of the sex industry.

Humanism is a religion that is often mistaken as a philosophy. Like some strands of “Hinduism”, Scientology, “mystical” Quakerism and Hermeticism, Humanists believe that individuals can achieve a god-like status through reason and knowledge— the same Pymander ideas I just described. Humanism, like Hermeticism, got a foothold in Europe largely thanks to the same Medici translation program which Cosimo Medici paired with “Symposium”-like schools for young boys. The net result of the Medici cultural reeducation program was “Renaissance Hermeticism” and “Renaissance Humanism”, and according to the Oxford University Press:

Indeed, the Latin, Arabic, Hebrew, and Byzantine Middle Ages offer an immense repository of Platonic and Hermetic wisdom to Renaissance humanists and philosophers, which includes new theoretical and practical approaches, interpretative methods, translations, and commentaries.

… and insights into military and cult psychology!

*(An argument could be made that this type of school-age indoctrination was also practiced in Ancient Greece, though it was certainly not paired with slavery or social vulnerability there, it focused on aristocratic children.)