Monarchist Founding Fathers

The Livingston family came to my attention as investors in John R. Freuler’s Mutual Film company: Crawford Livingston Jr. was a silent partner alongside Otto Kahn and the Shallenberger Brothers. Freuler was a Monroe, WI native and was the ultimate first employer of Leon Goetz, as Leon worked for Freuler’s employees The Gruwells, who operated a movie theater in Monroe.

Crawford Livingston Jr.: “Three-quarter length portrait of Crawford Livingston Jr., a railroad man who lived in St. Paul, Minnesota. Crawford Livingston purchased the land and built the first parts of Forest Lodge, an estate near Cable, Wisconsin.” Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society.

Now a “Camp David for water issues”: Forest Lodge was build by Crawford in idyllic Bayfield County, WI in the 1920s— if there were any profits from partnering with John Freuler’s porn-enterprise, they probably funded this palatial cabin, now an H2O think-tank. “[Prof. Peter] Annin hopes the gathering facilitates a conversation “that helps forward the ball” on water issues. “Forest Lodge is a really great place for those kinds of conversations,” he says. “It’s an inspirational place.”” And how!

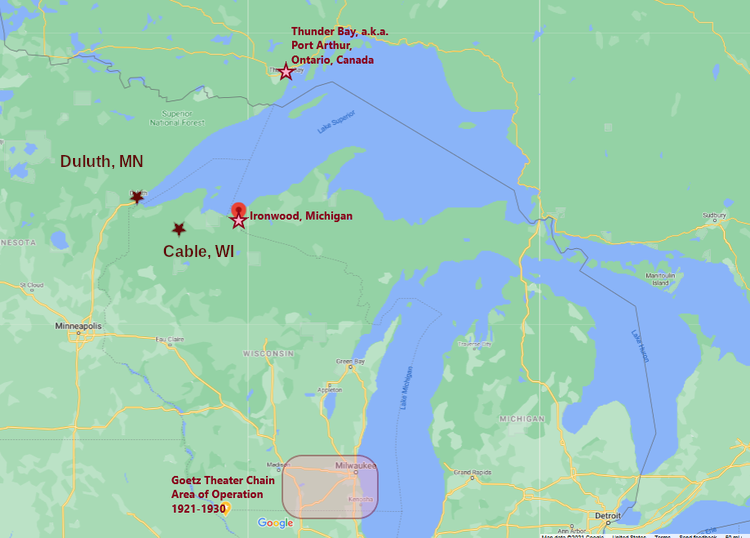

The Livingston compound at Cable, WI is situated in a woodsy, underdeveloped area and was developed during Prohibition, when alcohol smuggling across the Great Lakes was big business— big enough to interest even the Livingstons. See Cable in relation to Ironwood, MI, where Leon had his anomalous Prohibition-Era movie theater, and to Port Arthur, Ontario, ground zero for Leon’s weird submarine patent in 1909. The Livingston Family would become Brahmins of Minneapolis, MN, too. To understand Livingston investments in the NYC sex trade circa Edith May and the Ziegfeld Follies, see The Mutual Film Corp Submarine Connection.

Besides being prostitution magnates, financiers for pirates and gate-keepers/agents for American Indian mercenaries, the Livingstons were consummate politicians who manipulated our early democratic institutions in service of their monarchist agenda. They would use their newspaper investments to incite riots against their political enemies, then sell out the electorate once Livingstons held positions of influence, while packing the judiciary and law enforcement mechanisms with their cronies. They only sold out the British king once the prospect of their absolute power in the New Jersey colony became a possibility— circa 1775.

According to the personal papers of William Livingston (1723-90) and his second biographer James Gigantino II, this family’s New-World goal was to recreate the feudal system they enjoyed back in Scotland under the Stuarts. To that end, they supported the British Monarchy, but not the British Parliament. They understood that the key to their design was controlling large bodies of fighting men— the old mercenary warlord model. Their serfs were not black slaves nor American Indians, their serfs were the humble white settlers who did the bulk of the work making New England valuable farmland. In light of this, Livingston political policies were remarkably like those used by Enlightenment-era absolutist rulers back in Europe: repress the economic and political power of the middle- and artisan-class, while manipulating Enlightenment rhetoric to drive a wedge between these artisans and and power-sharing structures. In the North American case, that wedge came between white laborers and the British Parliament; in Europe, the wedge was forced between common people and their native aristocracies. No matter where they were, for absolutists one thing stayed the same: Democracy in theory, never in practice.

Many readers may be surprised to learn that pseudo-democratic forms of government were a favorite tool for absolutist, imperialist rulers so I’ll take a minute to explain this curiosity of history. In the latter half of the 1700s, a cynical use of enlightenment/democratic ideals was very much in vogue among European rulers who sought absolute power. Most enlightenment publishing was directly or indirectly funded by absolutist rulers. No less that the Marquis de Pombal, creature of Empress Maria Theresa, expressed his contempt for George III’s unwillingness to grant colonists a form of ‘democratic’ representation. In the words of historian Kenneth Maxwell:

“The tactics of the Anglo-Americans, Pombal observed during November 1775, were identical to those of the “good Portuguese vassals of Pernambuco and Bahia.” George III's armies would never defeat the rebels though the loss of British America could be avoided, he believed, if London acted prudently and permitted the colonists their own parliaments, which could always be controlled by royal office holders and by patronage.” [Maxwell, Kenneth. “Pombal: Paradox of the Enlightenment” Cambridge University Press, 1995.]

A ham-fisted version of this same scheme was precisely the plan implemented in Austria-Hungary by Emperor Franz Joseph, which I wrote a bit about in Rainer Hapsburg: The Bicycling Archduke?

“If I May”: arms of the Livingston family of Callendar, thanks New York Genealogical Society.

If George III was unwilling to manipulate New World democracy to preserve his rule, the Livingston family certainly were. This family were down-on-their-luck British aristocrats who’d lost power alongside the Stuart dynasty and held an inter-generational grudge against Parliament. When Robert Livingston, a radical protestant preacher, immigrated to Dutch-speaking colonial New York, he sought to rebuild the family’s power-base in the New World. His methods for doing so were the tried-and-true methods of medieval mercenary-lords: controlling land and sea piracy. To do this he sought out the preeminent position of influence mediating between Indian tribes (North America’s answer to Europe’s medieval mercenary soldier) and colonial governments, as well as financing “privateering” (pirate) organizations on the seas, like Captain William Kidd’s outfit.

Life under Mercenary Warlords: A ‘bastle’ house in Cambro, Northumbria, which is part of the once-fractious border region between England and Scotland, the Livingston’s home-country. Bands of mercenaries and marauders would plunder farmers, who responded by building fortified homes. “Bastle Houses are generally two-storey fortified farmhouses, with living accommodation on the first floor and shelter for cattle and sheep on the ground floor. They were built around the Anglo-Scottish border areas, during times of frequent attacks and raids by the Border Reivers, and hostilities between England and Scotland. Typically, Bastle Houses were homes and refuges for rich freeholders, lairds and heads of Border clans. Bastles were often built in clusters, so that the inhabitants were within easy reach of their neighbours, providing support for each other. Some of the more wealthy landowners had Pele Towers, which were taller than bastles, usually with three or four storeys.” From https://co-curate.ncl.ac.uk

Life under Mercenary Warlords: The General Adam Stephens House in Martinsburg, WV. Gen. Stephens was born in Scotland and shared command of the frontier defenses with George Washington during the French and Indian War. His 1770s/1780s bastle-style home is built on top of a natural limestone cave system as a safety procaution against Indian raids or other military attacks. Livingstons were responsible for mediating with New York-area ‘Five Tribes’ Indians who would send raiding parties into Virginia to target poor farmers, and occasionally rich ones. To be defenseless (peaceful) was to put a target on one’s back; settled Indian farmers were also targets for the bandits. From WVencyclopedia.org

Robert Livingston sought out his Indian connections with purpose, and ensured his heirs maintained the same influential position (‘Indian Agent’) with regard to the tribes and the colonists. For generations, the Livingston family were the clearing-house for Indian-derived intelligence in the New York colony and beyond. By maintaining this position, the Livingstons set themselves up as mediators between radical Protestant investors from Europe (like Count Nikolaus Zinzendorf) and some Indians who genuinely believed American Indians were one of the Lost Tribes of Israel. These ‘Lost Tribes’ were part of an ancient Jewish myth that ‘explained’ the diversity of races on the planet and was used to justify both Jewish and radical protestant beliefs about their special relationship to God. From a radical protestant perspective, the Livingstons made themselves spokespersons for God’s People on Earth. Nice work if you can get it.

Some ‘Indian Agents’, for example Joseph M. Street, conducted their role in a responsible way which lead to their being esteemed by both the Indian tribes they represented as well as their settler/colonial contemporaries. Others, like Robert Livingston and George Davenport, abused their position to enrich themselves— to the extent ‘stealing land from the Native Americans’ actually happened, it did so through the machinations of sociopathic ‘Indian Agents’ who cared as much for the Indians as they did colonial settlers. (And sociopathic Indian leaders who were willing to sell out their brethren, or a neighboring tribe.)

Robert’s son Philip relocated to Albany, rather than live at Livingston Manor (Columbia County, NY), in order to preserve his lucrative dealings with the "Five Tribes”:

“His [Philip Livingston’s] connections with Indians also allowed him to become one of the largest speculators in western New York; among several problematic land deals he signed was one agreed to by three supposedly intoxicated Mohawks for 8000 acres.”

William Livingston, the Revolutionary War leader and governor of New Jersey, was Philip’s eighth son. While growing up William saw Indians frequently visiting to converse with his father, and it wasn’t long before William himself facilitated Imperial British interests and intelligence gathering:

“In 1735, at age twelve, William accompanied [Henry] Barclay on a yearlong mission to the Mohawk under the auspices of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts [SPG], during which he continued his classical education while also learning much about Indian customs and culture.”

[Henry Barclay was a rector of Trinity Church on Wall Street in NYC, and responsible for fulfilling the SPG’s responsibility to the British Government’s Board of Trade, which sent many Calvinists, Palatine Lutherans (Germans) and French Huguenots to be tenants to Indian landlords, working to supply the British Navy’s requirements. These people’s beliefs had to be controlled. See Diffendal, Anne Polk, "The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts and the Assimilation of Foreign Protestants in British North America" (1974). University of Nebraska-Lincoln: Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History. 76.]

The Society for Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts was one of two organizations founded by Anglican Rev. Thomas Bray with an eye to checking Quaker and Catholic encroachment into British Colonies. The other, The Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge, was his partnership with the Pietists out of Halle in the Prussian-dominated portion of the Holy Roman Empire— an undertaking designed to manipulate German expatriates in British lands, particularly German merchants in London, who came to control the economy of the empire during the 18th century. Young William’s involvement in the SPG essentially made him an intelligence agent. This is how Oxford University Press describes the SPG:

The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG) was a Church of England missionary organization active in the British Atlantic world in the 18th and 19th centuries. Founded in 1701 by Reverend Thomas Bray … [it] lobbied for a more expansive place for the Church of England in Britain’s burgeoning empire. In total, the SPG supported more than four hundred overseas agents in the 18th century. Bray and his collaborators believed …. that dissenters, especially Quakers, exercised too much influence in the colonies. Many SPG supporters also looked on global Roman Catholic missionary activity with a mixture of awe and hostility, and envisioned the organization as a counterweight to the Jesuits and other Catholic orders. The society focused its attention on British colonies without strong Anglican legal establishments. As a result, while its role in the Chesapeake and most Caribbean colonies was minimal, the SPG was continuously active in the lower South, the mid-Atlantic, New England, Bermuda, and colonies that would become part of Canada. It also operated in Barbados, where a charitable bequest aimed at establishing a college made the society owners of a slave-worked sugar plantation, and it launched the first British missionary program in West Africa beginning in the 1750s. … It also worked, albeit with mixed results, toward the Christianization of Native Americans and free and enslaved Africans and African Americans. The society’s original charter confined its operations to Britain’s colonies, so its activities in much of mainland North America ceased with the establishment of an independent United States in 1783.

That’s the year the Quaker pimps were driven out of NYC along with the British military.

A portrait of Anglican missionary, abolitionist and Imperial British intel agent Rev. Thomas Bray.

William’s involvement with the Anglican lobbying organization, presumably with his father’s blessing, offers a fascinating insight into the psychology of the Livingston family because at some point during William’s childhood the family themselves identified as dissenters— ‘Dutch Reformed Church’— and then again prior to William’s adulthood they converted to Presbyterianism, another dissenting form of Protestantism. The Livingstons were Anglican-sympathizing dissenters spying on other dissenters. By the time of William’s young adulthood, he professed a “flexible” type of Presbyterianism, which was “liberal in doctrine and interdenominational in character”, i.e. something resembling Quakerism, but out-Quakering even the Friends, William refused to commit to their hazy ethics. It is an inter-generational characteristic of the Livingston family to say one thing and do quite another.

I’m going to look in depth at how the Livingstons manipulated colonial politics in the New York territory, which goes hand-in-had with how they got their wealth. This story will be eerily familiar to anyone following contemporary American politics.

In addition to ‘interfacing’ between the leading American Indian economic activities, mercenary fighting and the fur trade, the first New World Livingston, Robert, married into the wealthy Van Rensselaer patroon family. (That name will feature prominently in the Livingston’s oppression of tenant farmers.) According to Governor William Livingston’s biographer James Gigantino Jr.:

“he [Robert] became heavily involved in financing privateering operations and trading in furs, foodstuffs, and luxury goods from Europe to the Caribbean, New York and New England. He purchased lands “under dubious circumstances from local Indians” which totaled 160,000 acres around Livingston Manor, the family’s political and economic base.”

Philip also increased family investments in the African slave trade and concomitant trade with the Caribbean and Europe. European radical protestants had for a long while viewed Catholic empires’ Africa trade with jealously and by the 1700s they were in a position to challenge French, Spanish and Portugese trade through legal and illegal networks. The vast majority of African slaves were brought to the New World (North and South America) via illegal “interloping” trade, as high as 80%.

By William’s time, the British government discouraged the Atlantic slave trade because it was important to their enemies the French. (The Brits always turned a blind eye to the Hapsburgs’ Mediterranean slaving.) While William gave some lip-service to abolitionism and insisted any free blacks should vote (it would dilute the political power of the serfs), William himself acquired slaves throughout his lifetime. He appears to never have owned more than 20 people, however. The vast majority of his wealth came from the white tenant farmers whose votes he so feared.

So how did an imperialistic, duplicitous, abolitionist/slave-owner, anti-white-worker/democracy proponent become one of the “Founding Fathers” of the American Revolution of 1776? The short answer is that William was still fighting the English Civil War one hundred years after history tells us it ended.

James Gigantino Jr. is one of only two biographers of William, and is overall a sympathetic biographer. He summarizes William’s motivation:

“[William] Livingston epitomizes those founders who saw the revolutionary movement in royalist terms. Several founders believed that Parliament had usurped the prerogatives of the crown after the Glorious Revolution and inappropriately interfered with issues, including colonial affairs that should have been the sole province of the king. Livingston and others hoped George III would exert a stronger executive authority against Parliament, though popular Whig ideology that converted many to republicanism soon overtook this line of reasoning as the war began. This popular ideology-- something Livingston never took comfort in-- remade New Jersey’s patriot government and led to Livingston’s ejection from the Continental Congress in June 1776 for his continued opposition to immediate independence. Livingston never abandoned his royalist leanings and retained both a strong interest in greater executive authority and a healthy suspicion of legislators, beliefs that dramatically affected how he prosecuted the war in New Jersey.”

What the Revolutionary War offered Livingston, and what made him turn on the king, was the promise of absolute power. William exercised his role as a war-time governor in New Jersey as an absolute ruler, defining ‘public enemies’ as it suited his own agenda— what the British would call ‘A Law unto Himself’. This was the fulfillment of a long-time family aspiration, something they were very close to under the Stuarts but did not attain even then. Fortunately for history, patriotic colonial legislators— often from slave-holding Southern states— cut him down to size, but the Livingston family was not tore out by the root. In light of their aspirations we should not be surprised to find Crawford sniffing around what became the ‘Hollywood Empire’ circa 1910.

Megalomania is not an attractive trait, but fear is even uglier. By 1774 the Livingstons lived in fear of their tenants, who had been pushed to their limit via the debt-economy and land seizures which benefited the Livingstons and other “proprietors” of George III. Tenants were increasingly willing to “riot”— take arms or protest— in service of their interests and the Livingstons could largely blame William for this violent turn.

While Gigantino is sympathetic, he does not run from a handful of William’s ugly character traits: He was a “propagandist for his family’s political machine” who exploited that same “popular Whig ideology” when it suited him. He was a “behind-the-scenes leader” adept in “surreptitious political maneuvering”, and with regard to the way he treated other people “...his family’s experiences with debt, tenant uprisings, and trade strongly influenced his political beliefs”.

Time and time again William used his New York City newspapers, The Independent Reflector and The Sentinel, and columns in the like-minded publication New York Mercury to “wage war” against his political opponents the De Lanceys or Anglicansim (the worm had turned!) and argue in favor of “limited government and the power of natural law” (Englightment/ republican/ Whig propaganda).

The Triumvirate [William Livingston and his lawyer/newspaperman propaganda crew] published a series of articles called The Sentinel to capitalize on the general weariness of British power as the rising prices of goods and the downturn in the Atlantic trade had caused food shortages and compelled the introduction of price controls by 1763… Livingston used this rhetoric of liberty to persuade middling New Yorkers that the Forsey case represented a chance to defend a system of governance that rewarded local control and limited intervention by Britain. For average New Yorkers in the midst of an economic downturn, Livingston’s defense of liberty made sense in an ever increasingly difficult political and social situation. [Gigantino]

William’s fire-starting culminated in the Stamp Act “rioting” of 1765, which gave William pause to consider where his interests lay [Gigantino]:

The conservative lawyer [William Livingston] had become increasingly uneasy about the mob violence that had become more commonplace in New York by the end of 1765. In late August, Livingston published he last Sentinel essay after the Stamp Act riots in Boston and the formation of mobs to destroy the stamps delivered to New York. Despite the efforts of Livingston’s nephew James Duane and cousin Robert R. Livingston, mob action intensified. In late October, merchants in New York agreed to a boycott, and on November 1 more than two thousand men gathered to protest the Stamp Act, hanging Colden [Livingston adversary] in effigy. Despite the fact that these protestors made up a sizeable number of the electorate, as most had paid the one-time fee to declare themselves freemen and therefore eligible to vote, Livingston and his family soured on such tactics and the wanton violence they witnessed in October and early November 1765. William Smith Jr. [part of Livingston’s political machine] remarked that the violence had created “a state of anarchy” in the city and threatened a civil war, leading Livingston to join the conservative backlash against the democracy that the crowds represented.”

The successes of the “Sons of Liberty” making their voices heard gave courage to the tenants whom Livingstons and other ‘colonial aristocrats’ had abused. As NY ‘political activist’ Al Ronzoni writes:

Encouraged by the 1765 Stamp Act riots in New York City, upstate tenant farmers began to offer stiffer resistance to landlords. They soon formed their own militia bands; elected their own officers; formed popular courts to to try “enemies” they captured; threatened landlords with death; restored evicted tenants to their farms and broke open jails to rescue friends. As Nash tells us, “In effect, they formed a countergovernment,” that was seen as the height of treason by both the landlords and British colonial authorities. [Gary B. Nash, “The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America”]

Gigantino dismisses these farmers’ grievances as a fracas over “squatters’ rights”, but this is a gross misrepresentation of the truth. (Gigantino built his career publishing at the University of Pennsylvania Press.) By the time of the New York Tenant Riots of 1765, the New York colony’s white farmers had endured decades of theft and abuse from 1) the Livingstons and the other “patrician” families the Livingstons had married into and 2) the colonial government structures which the Livingstons had packed with their agents. William himself built his early career codifying his family’s thefts into law retroactively.

The New York tenant troubles started in the in the 1690s, when the colonial government was hungry for land developers and over-stretched surveying land. For example, an 180,000 track of land was ‘fuzzily’ granted to “Sybrant and Dorland” between the Hudson and the Connecticut border, conditional on the two men obtaining an “Indian patent” (a document which recognized Indian rights to land in question and formalized how much rent would be paid the tribe) and that a more detailed land survey be conducted. [See “Land Heist in the Highlands: Chief Daniel Nimham and the Wappinger Fight for Homeland”, by Peter Cutul.] This Indian patent and survey were never accomplished and Wappinger Tribe lands— a tribe of about 200 men who sold themselves as mercenaries to the British— were bound up in the resultant legal mess, partly because they were renting land to white tenant farmers which was fuzzily included in the original “Sybrant and Dorland” pseudo-grant.

Generations passed and in 1756 the “Sybrant and Dorland” land, never legally deeded nor properly surveyed, was owned by “Robinson, Morris and Philipse”. Cutul:

In 1756, taking advantage of the fact that the Wappinger men were off fighting for the British in the French and Indian War, Robinson and Morris began an aggressive campaign notifying tenants on Wappinger land that they had to sign new leases or vacate. Some of the tenants had leases with the Wappinger going back 30 years or more.

When the Wappinger returned from fighting for the Crown in the French and Indian War they were dismayed to discover that not only had their hunting grounds been disturbed, but that their land had also been claimed by Robinson, Morris and Philipse. Their consternation led Chief Nimham, representing the tribe, to file a claim against the landlords in 1762.

The Wappinger’s white tenants paid for tribe leaders to travel to England for an audience with the king because no honest hearing of their case could be had from New York’s Livingston-stacked courts despite what Cutul characterizes as rock-solid evidence and competent legal representation. The king of course did nothing and hell broke loose for the white tenants, with a Livingston leading the horde:

Robinson and Sheriff James Livingston wasted no time in evicting tenants unwilling to sign one to three year leases and pay rents in cash (traditionally rents were paid in agricultural products). Resistant tenants were harshly dealt with, some even being burned out of their homes. A Connecticut lawyer, who anonymously wrote a firsthand account of the situation made this observation:

“The said Mr. Robinson without any manner of legal warrant, or authority for so doing, thereupon having collected a body of upwards of 200 soldiers, consisting partly of regular troops and partly of militia of the said province, all well armed, and supplied with ammunition, and other warlike apparatus besides wagons and wagoneers; in a warlike posture march’d up against the poor, defenceless people, under a pretence of subduing the rebels, giving out, that they had acted in open rebellion to the Crown of Great Britain, that were a pack of Rebels! Damned Rebels! And Traitors! And upon a Sabbath day, long to be remembered, arrived among the inhabitants aforesaid, and in a hostile manner, drove them out before them, burnt and destroyed some of their houses pillaged and plundered others, stove their cyder barrels, turned their provisions out into the open streets, ript open their feather beds, laid open their meadows and fields of grain, and either took, or destroyed the greater part of the effects of this poor, but loyal people.”

The Wappinger were not molested to the same degree by James Livingston, they became mercenaries for the Continental (William Livinston’s) cause during the 1775 military build-up which so enticed William, and were mostly wiped out fighting their one-time paymasters.

It was during James Livingston’s Wappinger-land farm-burning that William Livingston used his NYC newspapers to attack his political opponents with “rights of man” ideology. William’s tactic won a short-term battle against the De Lanceys, but ultimately undermined the Livingston family finances. Gigantino:

New York’s middling and lower classes were confirmed in their perception that Livingston had abandoned them after he and his family battled against the 1766 Hudson River Valley land rioters. The large manors established along the Hudson River had been sites of agrarian unrest since the 1750s, when disputed land titles had caused tenant uprisings on Livingston Manor and other estates. Williams’s brother Robert crushed the uprising in 1766 and retained William as counsel to eject the rebellious tenants, based on William’s prior experience representing tenants living near Elizabethtown, New Jersey, against their landlords on essentially the same type of land disputes. The 1766 uprisings again involved disputed land titles and began in Dutchess County, New York, spurred by the rhetoric of the Sons of Liberty during the Stamp Act crisis. These farmers, some of whom participated in the mob violence in New York City, adapted Lockean notions of property to justify their squatter rights against the land titles claimed by the manor lords. William Prendergast, leader of the Dutchess county uprising, even called the rioters “Sons of Liberty”. On June 19, 1766, two hundred tenants marched on the Livingston manor house, demanding free leases; they were repulsed by a group of armed men led by William’s nephew Walter, and British troops were dispatched to restore order to the estates.”

Livingstons would always be at odds with their tenants until their aristocratic privledges were finally revoked during the 1830s-40s— perhaps the most interesting 20 years in American history.

The plaque above reads: “Historic New York, Livingston Manor. In 1686 Governor Dongari confirmed the grant of a manor of 160,000 acres of land along the Hudson River to Robert Livingston (1654-1728). Livingston as lord of the manor exercised extensive powers over land and tenants. In 1715 a new patent gave the manor a seat in the colonial legislature. The founder's third son Robert was given a 13,000-acre tract in the southern corner of the manor where in 1730 a house was built and named “Clermont.” During the Revolution this lower manor house was burned. Rebuilt and occupied by Chancellor Robert R. Livingston, it gave its name to Robert Fulton’s steamboat, which the chancellor sponsored.

Tenants on the manor were few until 3,000 Palatine refugees were settled there by Governor Hunter in 1710 to make naval stores. With the failure of the project, they moved on to Schoharie. Later more tenants arrived and the crops, mines and manufactures of the manor flourished.

The numerous Livingstone family played prominent roles in the colony and early state, and, as aristocracy, dominated the life of this area. They were attacked in the “Anti-rent Wars” of the 1830's and 1840's, and lost their manorial privileges but continued to reside on their lands. Education Department, State of New York 1988 East Hudson Parkway Authority”

Although “Livingsotn Manor/Clermont” was burned during the revolution, we still have William Livingston’s opulent home at Elizabethtown, New Jersey named “Liberty Hall”. Here William tea’d with his loyalist relatives as he hounded other loyalists in New Jersey, the “cockpit of the Revolution”.

Interestingly, when Prendergast was apprehended, he was sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered, which was the typical sentencing for a slave rebellion leader in the colonies. However, Prendergast’s wife, a Quakeress, had the ear of the judge, Chief Justice Robert R Livingston, and arranged to have the sentence entirely lifted— which meant going to the highest authority in the empire:

In a dramatic last ditch attempt to save her husband, Prendergast’s wife, a Quaker named Mehetibal Wing, rode non-stop over 70 miles to personally petition the Governor to save her husband. Her tear-fueled, dramatic appeal worked as the Governor issued a stay of execution for Prendergast, awaiting word from the King as to his ultimate fate. Sometime in late January or early February of 1767 word arrived from the King declaring, “His Majesty has been gratiously pleased to grant him [Prendergast] this pardon, relying that this instance of His Royal clemency will have a better effect in recalling these mistaken people to their duty than the most rigorous punishment.” 37 Although Prendergast was now free, stripped of any ability to lead the insurgents, the rioters were ultimately put down for good in two skirmishes involving British regulars that occurred in Patterson, and near Quaker Hill, NY, not far from Prendergast’s home. Although two British soldiers were wounded in the Patterson battle, the rioters nonetheless were successfully dispersed and the movement quashed.

In an upcoming post I’ll detail Quaker involvement inciting slave revolts for the benefit of the British Monarchy (and their own benefit). In the meantime, I ask readers to remember Quaker involvement in the ‘serf riots’ in 1765-67 New York, which ultimately benefited the king’s proprietors in an political and legal climate which would otherwise be adverse to their land-grabbing.

While Quakers play an interesting role in the 1765 New York Tenant Riots, the Livingston role is far more prominent, Gigantino:

“Along with his nephew James Duane, William represented several Hudson River property owners in more than fifty cases in 1766 concerning the ejection of rioting tenants. His fellow Triumvirate members [NYC’s political operators-in-chief], Scott and Smith, served on a judicial proceeding that sentenced Prendergast to death [disemboweled, drawn and quartered!!-A. Nolen]. The legal actions reveal Livingston’s conservative nature. In his rejection of violence against the landed aristocracy and his resistance to any fundamental change to the colonial social order, he was not unlike many of his elite contemporaries, including most of his family. The Uprisings terrified Robert, the lord of the manor, as they “were utterly alien to the world in which” his family lived. However, this should not have surprised many, as he had consistently opposed several of the lower class’s most important issues. For example, as early as 1753 in the Reflector, Livingston railed against paper money, an expedient especially important to average New Yorkers in the 1760s debt crisis…”

As a final insight to William Livingston’s cynicism and ultimately stupid exploitation of enlightenment rhetoric in his newspaper articles, I offer the trouble he made for his in-laws, the Rensselaers. From Voices of A People's History, edited by Zinn and Arnove:

In New York, enormous tracts of land were given by the British Crown to the Van Rensselaer family. Tenants on his land were treated like serfs on a feudal estate. Parts of the land claimed by Van Rensselaer were occupied by poor farmers who said that they had bought the land from the Indians. The result was a series of clashes between Van Rensselaer's small army and the local farmers, as described here in newspaper accounts of July 1766. [ Voices of A People's History, edited by Zinn and Arnove]

Account of the New York Tenant Riots (July 14, 1766). [In Hofstadter and Wallace, eds., pp. 116-17. From the July 14, 1766. American Violence: A Documentary History, Boston Gazetteer or Country Journal]:

“Wednesday an express came to town... by whom we had the following particulars. That the inhabitants of a place called Nobletown and a place called Spencer-Town lying west of Sheffield, Great Barrington, and Stock-bridge, who had purchased of the Stockbridge Indians the lands they now possess; by virtue of an order of the General Court of this province, and settled about two hundred families; John Van Renselear [Johannes Van Rensselaer] Esq., pretending a right to said lands, had treated the inhabitants very cruelly, because they would not submit to him as tenants, he claiming a right to said lands by virtue of a patent from the Government of New York; that said Van Renselear some years ago raised a number of men and came upon the poor people, and pulled down some houses killed some people, imprisoned others, and has been constantly vexing and injuring the people. That on the 26th of last month said Renselear came down with between two and three hundred men, all armed with guns, pistols and swords; that upon intelligence that 500 men armed were coming against them, about forty or fifty of the inhabitants went out unarmed, except with sticks, and proceeded to a fence between them and the assailants, in order to compromise the matter between them. That the assailants came up to the fence, and Herman us Schuyler the Sheriff of the County of Albany, fired his pistol down ... upon them and three others fired their guns over them. The inhabitants thereupon desired to talk with them, and they would not harken; but the Sheriff, it was said by some who knew him, ordered the men to fire, who thereupon fired, and killed one of their own men, who had got over the fence and one of the inhabitants likewise within the fence. Upon this the chief of the inhabitants, unarmed as aforesaid, retreated most of them into the woods, but twelve betook themselves to the house from whence they set out and there defended themselves with six small arms and some ammunition that were therein. The two parties here fired upon each other. The assailants killed one man in the house, and the inhabitants wounded several of them, whom the rest carried off and retreated, to the number of seven, none of whom at the last accounts were dead. That the Sheriff shewed no paper, nor attempted to execute any warrant, and the inhabitants never offered any provocation at the fence, excepting their continuing there, nor had any one of them a gun, pistol or sword, till they retreated to the house. At the action at the fence one of the inhabitants had a leg broke, whereupon the assailants attempted to seize him and carry him off. He therefore begged they would consider the misery he was in, declaring he had rather die than be carried off, whereupon one of the assailants said "you shall die then" and discharging his pistol upon him as he lay on the ground, shot him to the body, as the wounded man told the informant; that the said wounded man was alive when he left him, but not like to continue long. The affray happened about sixteen miles distant from Hudson's River. It is feared the Dutch will pursue these poor people for thus defending themselves, as murderers; and keep them in great consternation.”

Bearing the above in mind, I ask readers to consider this quote from The Gotham Center for New York City History’s “Robert Livingston Papers” page:

But Livingston’s attitudes toward race and slavery were complex. When he served on New York’s Council of Revision, he helped veto legislation that provided for the gradual abolition of slavery but prohibited Blacks from holding public office and voting. Of emancipated slaves, Livingston wrote they could not “be deprived of those essential rights without shocking the principle of equal liberty,” adding, “Rendering power permanent and hereditary in the hands of persons who deduce their origins from white ancestors only” would establish a “malignant … aristocracy.”

That Livingston would characterize the vast white electorate as a “malignant aristocracy” makes more sense given his fear of being held accountable for his (and his family’s) actions. It was the power of patriots from slave-holding Southern states that checked William Livingston’s despotism during his Revolutionary hey-day. The Livingston Clan’s contempt for and fear of 1) checks on their power from the slave-holding South and 2) their white serfs played out in their hypocritical ‘support’ for abolition as well as their exploitation of black labor in NYC after the Revolution.

Prior to the 1820s New York City was a white city— the laboring immigrants who would have worked at Livingston iron mills or sugar refineries were usually Irish or German, or the children of tenant farmers from New York’s agricultural hinterlands. From at least the 1820s, local industrialists began to import black workers to depress wages— the same sort of greed that turned Livingston tenants sour to their overlords. As I mentioned in my previous post, Livingstons also owned the brothels that catered to these black workers. Working-class whites’ ‘toleration’ of wage suppression, economic displacement and sexual exploitation became the keystone for the Livingston family’s vast post-1783 profits.

Americans of today shouldn’t be surprised to hear the same rhetoric from modern Washington: these career bureaucrats and politicians are aping the old set of Livingston tropes which are motivated by the same fear of accountability. It is my hope that modern Americans will not make the mistakes of their Whig forebears by misunderstanding the Christian conception of “forgiveness”.