World War I and The Paramount Takeover

The history of early film prior to the establishment of sound pictures in the late 1920s has been neglected by academics-- this is acknowledged in the field. What works do exist focus on East and West Coast developments at the expense of the Chicago-Milwaukee axis, thereby giving a skewed and not very coherent picture of what was going on in the industry. Adding to the confusion is that, while focusing on NYC and LA-area events, academics insufficiently investigate the history of financial institutions behind the 'Majors'-- the post-WWI Trust-- thereby neglecting insights which Coastal histories can legitimately provide. It's a crazy state of affairs.

A consequence of this confusion is that the significance of WWI to the development of 'Hollywood' is obscured. The big events that decided which non-Edison companies would become the new, Roosevelt-Junta-Approved ‘Trust’ happened in the run-up to US entry into WWI. The first of these “big events” was the break-up of the “bad trust”, Edison's ‘Motion Picture Patents Corporation’ (MPPC), which was enabled via legal actions initiated by the freshly-minted Mutual Film president John R. Freuler. The second of the “big events” was Adolph Zukor’s takeover of Paramount Pictures in May of 1916.

Today I will share the extent of what I’ve learned about WWI-era film financing and the new ‘Majors’. Financing didn’t suddenly become important sometime during the 1910s or 1920s as is often parroted, it’s always been important to the film industry, and to understand the competing players we need to understand who financed the MPPC.

Edison's “Trust” was made up of Edison Studios (a movie producer) and the other leading movie-producing companies which banded together with him-- sometimes unwillingly as in the case of Col. Selig-- to protect their patent and financial interests from intellectual property thieves, the “independents” like Mutual Film. Edison Studio's key MPPC partners were: Vitagraph, Biograph, Essanay, Selig, Lubin, Kalem, Pathé, Méliès, and Gaumont. Biograph, more properly titled “American Mutoscope and Biograph Company”, was the home of star director D. W. Griffith prior to his defection (along with his star actors) to Mutual Film in late 1914.

Prior to Griffith's departure, Biograph had taken out substantial loans from the Empire Trust Company and was struggling to repay them. According to Trust Company magazine of March, 1904, the “Empire Trust Company” was founded that year by a merger of “McVickar” and “Empire State” companies. Below is an image from Trust Company magazine (p.299 of Vol.1 (1904)), which explains the new company:

The Empire Trust Company was an old-money NYC company. Harry Whitney McVickar, of McVickar Realty Trust, was the grandson of a fabulously connected Episcopal minister and cousin to John Jay— Jay was a US founding father and a leader combating British espionage. H. W. McVickar’s career was remarkable: a celebrated illustrator-turned-financier, he got his start in finance with the venerable van Renssellaer family. McVickar served as director of the Knickerbocker Trust Company and as treasurer of Gaillard & Co, according to his obituary in the July 5th, 1905 New York Times. McVickar and his wife also appeared in NYT’s February 16th, 1892 list of “the Four Hundred” best families in NYC. The Empire Trust’s leadership over the next decade seems to have been drawn from both New York City and Boston.

The following is from Trust Company, January 1907, which lists two new Empire Trust directors who do not fit the social scene described above:

It seems that this social trend continued through 1913, and while the core of Empire Trust remained the same as during its founding in 1904, exotic new investors were being included:

Trust Company, January 1913. p 130. Excerpt from “Empire Trust Company of New York City HEads Important Mergers”.

That the Empire Trust Company took on A. P. Heinze is a significant development. The Heinze brothers (Frederick, Albert and Otto) were risk-seeking copper magnates and wealthy German-Jewish immigrants like their rival copper magnates the Guggenheim family, who sat on the board of the Guaranty Trust Company. (The Guaranty Trust Company will play an important role enabling Adolph Zukor's takeover of the Paramount film-distributing company, which involved John Freuler and William Wesley Young's boss Benjamin B. Hampton.) We met the Guggenheims earlier through their association with Mischa Appelbaum of the Humanitarian Cult.

Smithsonian Magazine contributor Gilbert King gives us an overview of Frederick Augustus Heinze's (brother of A. P. Heinze) place in NYC finance:

In a rapid ascent, Heinze established the Montana Ore Purchasing Co. and became one of the three “Copper Kings” of Butte, along with Gilded Age icons William Andrews Clark and Marcus Daly. Whip smart and devious, Heinze took advantage of the so-called apex law, a provision that allowed owners of a surface outcrop to mine it wherever it led, even if it went beneath land owned by someone else. He hired dozens of lawyers to tie up his opponents—including William Rockefeller, Standard Oil and Daly’s Anaconda Copper Mining Co.—in court, charging them with conspiracy. “Heinze Wins Again” was the headline in the New York Tribune in May of 1900, and his string of victories against the most powerful companies in America made him feel invincible.

Due to the Empire Trust's substantial loans to Biograph an Empire Trust representative, Jeremiah J. Kennedy, became president of Biograph and “the dominant figure” in the MPPC, according to historian Janet Wasko in her paper “D.W. Griffith and the Banks” [1978]. We can say, therefore, that the Empire Trust represented those MPPC interests which were on the wrong side of the Roosevelt Junta.

Since late 1912, the Empire Trust's board of directors included Charles M. Schwab, the German-American financier who profited from the 1902 implosion of Teddy Roosevelt's/J. P. Morgan's/John Willard Young's (son of Mormon leader Brigham Young) disastrous “United States Shipbuilding Company”, which was designed to sneakily build submarines for the British.

During the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt, Heinze family manipulation of the copper market lead to a crash on Wall Street and the financial panic of 1907, which in turn triggered an unjust run on McVickar’s Knickerbocker Trust. The Knickerbocker was associated with the Heinzes because it had done business with them in the past, but Knickerbocker leadership wisely understood that the Heinzes didn’t have the resources to sustain their copper manipulation. When J. P. Morgan refused to extend Knikerbocker president Charles T. Barney credit during the run, Barney killed himself.

This unfortunate series of events and the demise of the Knickerbocker Trust in turn gave Morgan and Rockefeller interests the opportunity to increase their control of Federal and NY State finances via well-placed crisis lending. No doubt Teddy was grateful.

30 Rockefeller Plaza is probably the most famous of the 19 commercial buildings covering 22 acres between 48th Street and 51st Street in Midtown Manhattan which comprise “Rockefeller Center”. It was on the 25th floor of this building that Allen Dulles, an able organizer of pro-British war interests in the late 1930s, set up what would become the CIA. The Guaranty Trust would form two connections with Dulles’ henchman William Donovan in 1916, when partners of Donovan joined the Guaranty Trust board.

When Theodore Roosevelt's groomed successor Woodrow Wilson assumed office, his Department of Justice thoroughly destroyed the MPPC, a.k.a. the Empire Trust's control of the film industry. By 1937 British Film Council investigators F. D. Klingender and Stuart Legg found that Rockefeller and Morgan interests controlled the new “patents monopoly” of the film industry (a global monopoly) because they owned/controlled the patents involved exhibiting 'talkie' films. Patent control probably took second place to financial control of the film industry by the mid 1930s. Prior to WWI, financial control of the movies was still up for grabs.

Early film executives were a rough bunch, Edison’s MPPC crowd were genteel by comparison. One of the scrabblers, William Fox, had an acute grudge against the MPPC. According to Klingender and Legg, the reason for this grudge was as follows:

Excerpt from “The Money Behind the Screen” by F. D. Klingender and Stuart Legg, 1937.

Since Edison and the other leading MPPC players were no strangers to (quietly) providing bordellos with films themselves, the details of Fox’s behavior prior to the alleged entrapment must have been egregious. When Freuler’s legal actions in Mutual Film Corp. v. Industrial Commission of Ohio, 236 U.S. 230 (1915) established films as part of interstate commerce and subject to the Sherman Anti Trust Act, Fox took the next step assisting Teddy Roosevelt interests in the FTC to bring their case against his old rivals. Other investors were eager to cannibalize the body of the embattled MPPC.

The Guaranty Trust was a different animal to the Empire Trust. Guaranty's board of directors included two Guggenheim copper representatives (Daniel Guggenheim and William C. Potter); our old friend Thomas F. Ryan (Benjamin B. Hampton's old American Tobacco patron); James B. Duke, then chairman of the gently trust-busted (thank you, B. B. Hampton!) British American Tobacco; Albert Strauss of J. W. Seligman & Co. (the Humanitarian Cult Seligmans and Paul F. Warburg's stand-in at the Federal Reserve Bank); and J. P. Morgan's representative and Versailles Treaty éminence grise Thomas Lamont, among others. Thoroughly 'Teddy Roosevelt' interests.

Two topics (at least) were on the minds of NYC finance executives in 1916: 1) cannibalizing the former MPPC assets and 2) getting into WWI as soon as possible. What had not been decided was which side of WWI to enter. German-aligned interests like those of Kuhn, Loeb & Company, or newspaperman Edward Rumley, were not in agreement with British-aligned interests on this matter. The battle ground was Mexico.

Prior to the final months of 1915, the US government had supported Pancho Villa because US business interests (including Guaranty Trust interests) were angered by what they considered the previous Mexican government's pro-Europe economic favoritism. Historian Anthony Sutton writes this in his famous Wall Street and the Bolshevik Revolution:

"Payment for the ammunition that was shipped from the United States to the Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa was made through Guaranty Trust Company. Von Rintelen's [German Naval Intelligence Officer in USA] advisor, Sommerfeld, paid $380,000 via Guaranty Trust and Mississippi Valley Trust Company to the Western Cartridge Company of Alton, Illinois, for ammunition shipped to El Paso, for forwarding to Villa."

From “Shows Germans Financed Villa” New York Times, Jan. 8, 1919.

According to Senate hearings, the Guaranty Trust loaned $450,000. However, the Chase National Bank loaned $3 million, the Equitable Trust Company $1.8 million, and the Mechanics and Metals National Bank $1 million. However, most of the loans came from Germany. The Guaranty Trust transferred the money to the Mississippi Valley Trust Company in St. Louis.

1915 was also the time that Theodore Roosevelt used Imperial German money to promote his ‘Bull Moose’ campaign, a calculated move designed to harm the Republican party and which resulted in Woodrow Wilson’s election. In 1915 Roosevelt partisan Edward Rumley bought New York Evening Mail using Imperial German funds and allowed Roosevelt to propagandize from its pages. Because of this activity, Rumley was convicted of “trading with the enemy” in 1918, but pardoned by President Coolidge in 1925.

Until early 1916, Imperial Germany and Guaranty Trust interests had both supported Villa at the same time. However, in 1916 Villa made a stupid blunder by attacking Guggenheim family investments (American Smelting and Refining Company) and killing their American employees. Guaranty Trust interests no longer saw Villa as a ally, while Imperial German interests probably still did, because Mexican trouble absorbed US military attention. Villa would go on to raid US military installations on US territory-- killing civilians in the process-- as a short-term fix for his weapons shortage, which poisoned US sentiment against him further.

In 1914, prior to Villa’s break with NYC interests, Mutual Film (an investment of Kuhn, Loeb & Company) made its movie glorifying Villa “The Life of General Villa”. One year later, when Mutual made Griffith's anti-war epic “The Birth of a Nation”, Mutual leadership was divided on whether to fund the production, and Harry Aitken's 'unapproved' used of Mutual money to finish the film lead to his and D. W. Griffith's departure, and John R. Freuler's ascendancy as leader of the firm. When Griffith and Aitken left, they took Otto Kahn’s other film investment, Reliance-Majestic Studios, with them. “The Birth of a Nation” is the last project for which Otto Kahn's name was openly associated with Mutual Film.

When the US eventually did enter WWI against Germany in April 1917, the immediate cause was the “Zimmerman Telegram”, a German diplomatic message, decoded by British Intelligence and supplied to their US contacts. (This telegram is said to have exposed a German spy ring operating out of 55 Liberty Street in NYC-- the same building as pro-war agitator Franklin Delano Roosevelt's law office. There is no way of deducing the existence of this “spy ring” from the content of the telegram which, if the ring existed at all, implies that the company sending it on behalf of the Imperial German government, Atlantic Communication Company, had offices in 55 Liberty.)

55 Liberty Street, New York City.

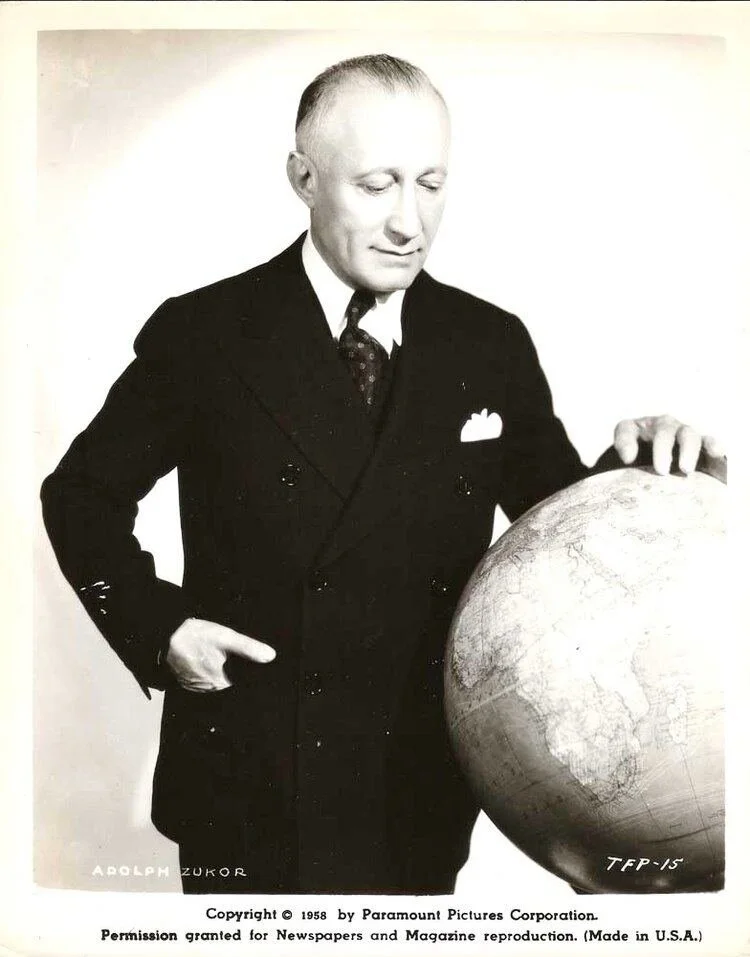

Bearing the above in mind, I'd like to talk a little about Adolph Zukor's “official” take-over of Paramount Pictures in December 1916, around the time Herbert Henry Asquith lost power as British prime minister. When David Lloyd George replaced Asquith, British Imperial policy changed in favor of creating a Zionist state in the Ottoman land of Palestine, which caused a sea-change in war politics along the Milwaukee-Chicago axis: men like Col. Fayban were now staunchly pro-British and pro-War.

Zukor was one of two contenders who sought to control Paramount, the other being Vitagraph heads Albert E. Smith and James Stuart Blackton, whose takeover strategy was guided by Benjamin B. Hampton and looked to the Guaranty Trust for key financing. (Guaranty wanted control of Paramount for as little risk to their own money as possible.) Vitagraph was the sole remaining MPPC movie producer which had survived Teddy Roosevelt's 'trust-busting'. Why were Zukor and Guaranty so keen to take over Paramount?

Paramount Pictures was a distributing conglomerate organized by William Wadsworth Hodkinson. Paramount’s “block booking” strategy of forcing exhibitors to buy bundles of movies was the most profitable strategy to date, because it artificially increased demand for the otherwise unsaleable bad movies which producers made— there were quite a lot of these. In order to show popular movies, exhibitors had to buy the flops in equal quantity. It was this portfolio of contracts with exhibitors and distribution infrastructure that made Paramount essential to anyone seeking to be the next MPPC. But who owned Paramount?

According to the Federal Trade Commission's 1928 investigation into Famous-Players Lasky:

“Said Paramount Pictures Corporation was organized May 8, 1914, by distributors of motion picture films as a National agency for the distribution of such films. The incorporators of said Paramount Co. and the owners of said corporation denominated in said business as franchise holders thereof, were nine certain corporations so engaged in distributing films.”

These nine owners of Paramount Pictures are never named outright by the FTC. However, sometime after signing five-year distribution contracts with Famous Players and Lasky on May 2nd, 1915, Paramount Pictures bought 51% “of the capital stock of the nine corporations that were its own franchise holders”. So Paramount Pictures owned a 51% stake in the corporate entities which had previously formed and owned it, including Adloph Zukor’s firm and that of his malleable partner Jesse L. Lasky...

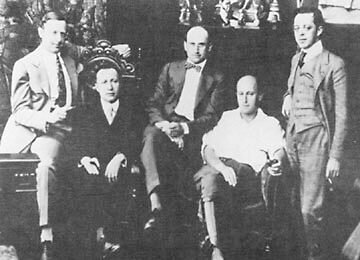

Zukor’s entourage: “1916 publicity photo for the takeover of Paramount Pictures. (L to R) Jesse L. Lasky, Adolph Zukor, Samuel Goldwyn, Cecil B. DeMille, Al Kaufman”. From speedace.info. The only one missing (to my knowledge) is the Judas-figure named Hiram Abrams.

One year later, on May 20th, 1916 Lasky and Zukor bought 50% of Paramount Pictures. The story goes that the 51% sale of Famous Players Film Co. and Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Co. to Paramount Pictures one year prior had generated enough cash to buy 50% of Paramount Pictures. There are two weird things about this situation:

1) Somebody had to be willing to sell 50% of Paramount to Lasky without Hodkinson being able to do anything about it. Paramount Pictures does not appear to have been a publicly traded company at this time, so the identity of the other seven “franchise holder” corporations; their creditors; and possible third-party Hodkinson creditors would be very interesting to know.

2) In his book An Empire of Their Own, author Neal Gabler states that together Famous Players and Lasky produced 75% of the movies distributed by Paramount Pictures. Therefore, the other seven “franchise holders” represented 25% of the movies distributed. It's difficult for me to see how 51% of 75% could be valued at the same price as 50% of 100%. Either a) something happened to eliminate the value of the other seven “franchise holders” between May 1915 and May 1916; or b) Lasky and Zukor got more money from a third source; or c) somebody sold their Paramout Pictures “capital stock” to Zukor and Lasky cheaply. I have seen no evidence of a) and I believe c) to be unlikely. Either way, some third force was involved in the May 20th 1916 purchase by Zukor.

In the months following his purchase of 50% of Paramount (a controlling interest), Zukor merged his company with Lasky’s to form “Famous-Players-Lasky” (FPL); ousted Paramount founder and president Hodkinson; replaced Hodkinson with Hiram Abrams as president; and sought money to buy the remaining 50% of Paramount “capital stock”. According to historian Kia Afra (The Hollywood Trust, 2016), the investment houses Zukor worked with to buy that outstanding 50% were:

The Irving Trust, which received two seats on the board of Famous-Players-Lasky, one of which went to Frederick G. Lee, who was the president of Irving back when it was called “Broadway Trust Company”;

the MPPC-controlling Empire Trust Company, whose vice president William H. English was also given a FPL board seat;

the German-American Bank, whose representative John F. Fredericks was given a FPL board seat;

and finally the Realty Trust Company, represented by William G. Demorest on FPL's board.

Note, because of Zukor's controlling position with respect to Paramount prior to his seeking money to buy outstanding Paramount stock, none of the bankers above could expect to have a controlling interest in the new Famous-Players-Lasky-Paramount firm which their money made “official”.

The banking house which ultimately benefited from Zukor’s takeover of Paramount Pictures in 1916 was Kuhn, Loeb & Co., which organized the 1919 public sale of $10 million in Famous-Players-Lasky stock after Zukor had borrowed non-controlling loans from the different investment houses listed above. (Famous-Players-Lasky was valued at US$ 22.5 million in December 1916.) Writing in 1937, Klingender and Legg note that Kuhn, Loeb & Co. remained Zukor/Paramount’s “main banking affiliation” until “their latest restructuring”.

Readers will remember that it was Kuhn Loeb & Co., along with the Shallenberger Brothers and Crawford Livingston, who had backed Mutual Film since 1914. The departure of D. W. Griffith and Aitken in 1915 was a blow to Mutual, Freuler tried to replace Griffith with acting stars like Chaplin in February 1916 and less-capital intensive “series” film offerings, but this strategy ultimately failed. Timothy Lyons, author of The Silent Partner (1974), one of the main scholarly works on Mutual, sees 1916 as Mutual’s zenith and the period of Freuler’s presidency as a two-year decline. As support for this assessment, Lyons offers the opinion of no less than Benjamin B. Hampton:

Benjamin Hampton, himself a producer during this period, suitably characterized not only Aitken the producer but also Mutual Film Corporation during Aitken’s tenure:

“Aitken, gifted with unusual personal persuasiveness, was an exceptional promoter and business builder, with rare talent for persuading directors, players, bankers to conform to his plans.”

It is possible that John R. Freuler, while gifted at organizing other film executives, was not the type of man Otto Kahn wanted to do business with: Mutual was money-starved and dead by the end of the war. There were some services that Freuler could provide to Kuhn, Loeb & Co. on his way out, however…

If Kuhn Loeb & Co had an investment strategy for the film industry and limited funds to pursue it, Kuhn Loeb & Co would have been wise to extend Zukor credit and whatever other help it could provide in early 1916. Kuhn Loeb & Co. would have had additional impetus to do this after February 26th, 1916 when Freuler signed the disastrously expensive Charlie Chaplin in the wake of a “badger trap”-style shake-down of his other investors’, the Shallenberger brothers’, business partner Robert Eastman by Chaplin’s gangster network. Who could blame Otto Kahn for looking for more controllable investment partners?

An unamused Freuler signs Charles Chaplin on to Mutual, which would be a dead company not long after.

Cecelia M. Virginia Davis, the vixen who Chaplin associates used to squeeze Eastman prior to Chaplin’s contract negotiations with Freuler. It’s possible that the only reason Chaplin made his short stop at Mutual was because his people had leverage over Eastman, and consequently Frueler.

Indeed, Kahn, as one of the most active investors in film, was likely in the loop about how to help Zukor, as Zukor wasn’t quiet about his intentions toward Paramount in May 1916. Evidence for this comes from Walter E. Green’s testimony, as provided by Hollywood Renegades author J. A. Aberdeen and credited to the New York Telegraph on May 1, 1923:

Walter E. Greene, vice president of the American Release Corporation, who was a partner with Hiram Abrams in an independent distributing exchange in 1916, told of the formation of the Paramount Pictures Corporation by a number of distributors from all sections of the country, of which W. W. Hodkinson of California was elected president.

Questioned by Mr. Farrington, counsel for the Commission, Mr. Green told how in May, 1916, Adolph Zukor, the president of the Famous Players Corporation, had become dissatisfied with the way its pictures were being handled by the Paramount Pictures Corporation and the witness said he had been told by his partners, Abrams and Alexander Lichtman, that Mr. Zukor had threatened to leave the Paramount Pictures Corporation, although he had a 25- year contract with it, unless some changes were made in its policy.

The witness said that following Mr. Zukor's return from a visit to California in May, 1916, that he, Abrams, Lichtman and Mr. Zukor had a conference at the home of the latter, at which Mr. Zukor said that he found it hard to get along with Hodkinson, and suggested that Hodkinson be removed as president and that Abrams be substituted in his place. He said they came to an agreement while at Zukor's home that if possible they would have Hodkinson deposed, and also the treasurer of Paramount Picture Corporation, a man named Pawley, removed. It was also agreed that Zukor should have 50 per cent of the stock of the Paramount Corporation. .

Kuhn Loeb & Co. might have extended help beyond money, as evidenced by the actions of embattled Mutual president John R. Freuler and Benjamin Hampton during Zukor’s takeover of Paramount in 1916.

According to Kia Afra, “a few weeks” prior to Zukors purchase of his controlling 50% stake in Paramount in May 1916 (so sometime in April or late March), Benjamin B. Hampton approached Blackton and Smith of Vitagraph, Zukor’s rival for Paramount, with a complicated plan whereby Vitagraph would borrow a staggering sum, helped by Guaranty Trust on the condition that Vitagraph eventually absorb Paramount pictures— to which, Hampton assured, Paramount’s president W. W. Hodkinson would be amenable. Before Paramount could be digested, Vitagraph would need to buy the General Film Company and the struggling Lubin, Selig and Essanay movie producers. All this borrowing would be paid for, said Hampton, because he would lure Mary Pickford away from Zukor and Lasky and deliver her to Vitagraph.

The linchpin to Hampton’s plan was poaching Pickford so her earning power could pay Vitagraph’s loans. According to his 1931 History of the Movies, Hampton had signed some type of time-limited, conditional, “option”-type contract with Pickford early in 1916, which he used as a bargaining chip in negotiations. According to Afra, Pickford’s penalties for voiding Hampton’s fuzzy contract were laughably light: she must only return the US$ 1000 check he gave her. Hampton told Vitagraph that Hodkinson would be satisfied with US$ 2 million in preferred stock from the new Vitagraph “supercombine”.

While Hampton was negotiating this plan with Vitagraph, he was also sharing information with Vitagraph’s rival Adloph Zukor, who, as Hampton claimed in 1931, was more enthusiastic about Hampton’s “supercombine” plans than his boss at Paramount Hodkinson, provided Zukor got an adequate share of the “capital stock”. Writing in 1931, Hampton claimed Hodkinson was always set against any mergers of distributors and producers— the exact opposite of what he told Vitagraph in 1916.

Benjamin B. Hampton kept Nicholas G. Roosevelt, first cousin once removed of Teddy Roosevelt, apprised of developments in his negotiations with Zukor and Vitagraph.

Interestingly, Vitagraph heads didn’t see Lasky and Zukor as meaningful competition, they were worried about a Triangle Film-Paramount merger. Triangle Film was the company Harry Aitken created when he and D. W. Griffith left Mutual along with “Birth of a Nation”, Otto Kahn’s Reliance-Majestic Studios, and other concerns. Triangle was seen as a producer of quality product, Lasky and Zukor worked hard to be seen that way, but questions remain in my mind as to whether contemporaries really saw them as such. Triangle was seen as the classy type of venture which would aid Otto Kahn’s much-publicized personal mission of engineering a new culture in the USA.

Smith and Blackton undertook a US$ 25 million restructuring loan for Vitagraph on the strength that Hampton could deliver his Pickford promise. This was far more than Vitagraph could afford, and only possible with the help of British accounting firm Price Waterhouse & Co.’s cooking their books. According to Afra, Hampton suddenly backed out of his negotiations with Pickford, forcing Vitagraph to continue them from a position of weakness, as Hampton’s Guaranty Trust backers also withdrew from the Vitagraph “supercombine” deal. In his 1931 book, Hampton claims he helped settle Mary Pickford’s differences with Zukor, so that she would remain with Famous-Players-Lasky. (She did.)

Hampton’s actions hobbled Vitagraph with debts that were never repaid until Vitagraph itself was taken over many years later— effectively, Hampton took Vitagraph out of the running for ‘next MPPC’. In order to keep going in the immediate aftermath of the Paramount disaster, Vitagraph was forced to take a separate loan from Guaranty Trust. Great news for Zukor and Kuhn Loeb!

Kia Afra muses on the preceeding: “In hindsight, the incident raises the prospect that Hampton’s option simply provided Pickford with leverage over Paramount’s board of directors.”

If Hampton’s actions worked against the anti-merger Hodkinson and hobbled Vitagraph, John R. Frueler’s did too. While Hampton was spinning his webs at Vitagraph and Famous Players, Freuler made a rich contract offer to Mary Pickford for US$ 7000 a week. She didn’t take it, but given Freuler’s recent handout to Chaplin, this offer stoked the bidding war over her and made the expensive merger business even more so.

I have reservations about using Terry Ramsaye’s work as a source, because his recollections are sometimes inaccurate. However, in this instance Ramsaye comes to a similar set of conclusions as Kia Afra. Ramsaye worked for Freuler’s investors the Shallenberger brothers at Photoplay magazine, and it was Ramsaye’s work there which informed Hampton’s 1931 book, The History of the Movies, wherein Hampton describes his negotiations with Pickford. In his 1926 book A Million and One Nights, Ramsaye recollects the following about Freuler’s Pickford bidding:

Freuler issued a “pink letter” to the Mutual’s branch managers, making inquiry about probable earnings on Pickford pictures in all parts of the country. The Mutual’s “pink letter” system derived its name from the color of the paper which denoted a confidential communication from the home office, to be kept under lock and key in a special binder.

Unfortunately this made it very convenient for the spies of competitive concerns to locate important correspondence. The offices of all the major film concerns were in this time sprinkled with espionage agents, planted as employees…Meanwhile the leaven of the Hampton promotional efforts was working. The motion picture industry was ripe for ferment. The old order of the nickelodeon age was sinking and the new dramatic feature period was uncertainly formative.

Within a week of the Pickford option, on March 23, to be exact, the rumors broke into print. The ’New York Times,’ without direct quotation of authority, discussed reports sufficiently comprehensive to indicate that anything, or everything, or both, would happen in the motion picture world….

The fact was, in this great tentative situation in the film industry, whoever emerged from the situation in possession of a contract with Mary Pickford was going to hold the whip hand in the whole industry.In some dim way every concern in the business realized this. The price of Mary Pickford became the price of supremacy.

The Mary Pickford bubble was calculated with an eye towards acquiring the much more valuable Paramount Pictures. While Guaranty Trust was important helping Hampton organize Mary Pickford for Adoph Zukor, Guaranty Trust investors were left in an unfavorable position— and certainly not in control of Paramount and the greater film industry as was their want. I have not come across much information on Hampton’s career after this time, either.

There is evidence that Zukor’s behavior over Paramount was unwise— that he made the foolish error of “dining alone”. With Guaranty Trust’s horse hobbled, disaster befell Zukor and his entourage at Paramount shortly thereafter. In the wake of a victory party at the Copley Plaza hotel in Boston, Hiram Abrams lead Zukor, Walter Green, Jesse Lasky, lawyer Joseph Levenson, Harry Asher and Edward Golden to a bordello named “Mishawum Manor” where madam Brownie Kennedy supplied the men with underage prostitutes.

Good Friends: “James M. Curley, Mayor of Boston, is shown with Democratic presidential candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt during the presidential campaign in Groton, Mass., near Boston, Oct 30, 1932. Curley seconded Roosevelt’s nomination at the Democratic National Convention.” From Boston Herald.

Corrupt Boston politician Mayor Curley was the intermediary between the Movie Moguls and their extortionists, lawyer Daniel Coakley (who enjoyed long-standing Roosevelt support) and Nathan Tufts, the Middlesex County District Attorney. The Coakley/Tufts duo, like Charlie Chaplin’s gang, had made an art of the “badger trap” shake-down. Zukor and his crew paid Coakley and Tufts at least US $100,000 to keep quiet, but the pressure wasn’t released on Zukor until around 1921. In the meantime, Zukor put his Hollywood resources to good use during the Roosevelts’ war on a committee that was run by one of Flo Ziegfeld’s early investors and President Wilson’s anti-porn Tsar…

Motion Picture Herald, March 28th 1942