Fake $500 Bills in Civil War Wisconsin

July 2025 Update: My book, Lincoln’s Counterfeiters, is now available for sale! It has updated information on everything in this post. The full story is even more astounding than I understood when I wrote this article a few years ago.

You can buy my book online here, via Amazon, Barnes & Nobel, Target etc. or in Monroe, WI at Martin’s Sporting Goods (Monroe East Side) and Perk’s Coffee Cafe (Monroe West Side). Thank you!

Original post continues:

Tom Mitchell’s pioneering work on the Bonelatta Counterfeiting gang in Monroe, WI was an eye-opener for me. (Join the Green County Historical Society to get a copy of Tom’s September 2021 Bonelatta writings and enjoy more of his work!) However, there is a vein to the story which remains to be mined out: why on earth was the Bonelatta crew’s star counterfeiter creating $100, $500-denomination US treasury bills during the foundation of the National Banking System?

This information comes from an account written 30 years after the Bonelatta prosecutions (1906) by serialized author Capt. Patrick D. Tyrrell. The Government Blue-Book: A Complete History of the Lives of all the Great Counterfeiters, Criminal Engravers and Plate Printers by John S. Dye records a P. D. Tyrrell as being an active government agent investigating counterfeiter John Peter McCartney in 1867. This 1880 account also confirms that Tom Ballard counterfeited $100 and $500 bills:

…also in due time (1862+), a plate for counterfeiting the One Hundred and the Five Hundred Dollar Old Issue United States Treasury Notes, and an immense amount more of the same general description, just as the supposed emergencies of a vast scheme for counterfeiting the United States currency required.

Tyrrell could easily have been one of those shady Treasury agents tasked with quashing politically unfavored counterfeiters. Tyrrell was certainly well versed in the Ballard case, and his writing was, for instance, printed in The Menasha Record on January 5, 1906, under the title “Stories of the Secret Service”. The relevant excerpt below:

What is an “old issue” note? To the extent I can answer that question, “old issue” was a term used to describe notes issued in previous accounting periods throughout the 1860s, ie. before and after the introduction of the “greenback”. In this excerpt I do not believe the phrase tells us much about the bills in question except that they were issued in an accounting period prior to the Secret Service investigation in 1871.

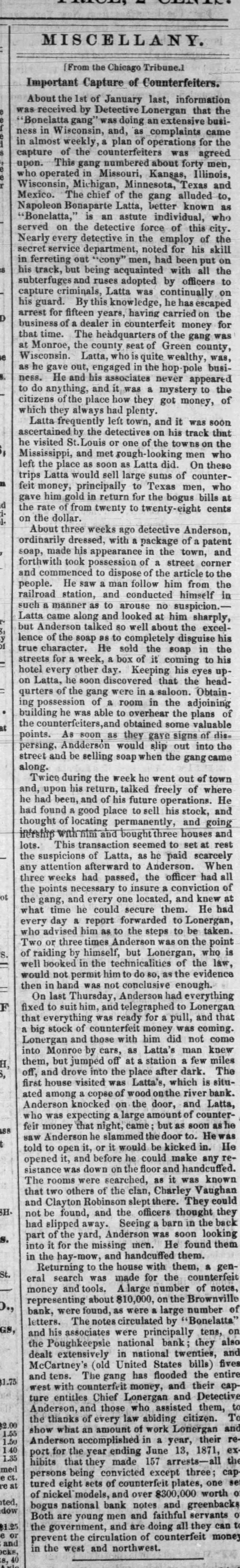

Most contemporary (1871-73) Bonelatta press downplayed the fact that “greenbacks” were circulated by the gang, one exception being the Chicago Tribune reporting below:

Fall River Daily Evening News, January 12, 1871.

Bear in mind that in the 1850s-70s a well-to-do person could buy an up-market house for US$ 700. Most daily necessities like flour were measured in pennies or single-digit prices. Regular people used coinage and small-denomination bills. Most counterfeiting crime was based on cheating shopkeepers or low-information wage earners (like German immigrants here in Green County). These victims would likely never see a $100 bill in their life. So why counterfeit these huge denominations?

This image is from the Smithsonian Institution’s collection:500 Dollars, Legal Tender Note, United States, 1869. Printed for the Bureau of Engraving and Printing by the American Bank Note Company, Inc. in NYC. This is the type of bill the Bonelattas would have been distributing throughout the Middle West and down into Mexico.

Reverse of note pictured above.

Why the huge denominations? Short answer: Lincoln’s financial wizards harnessed the power of turning federal debt into paper money, a counterfeitable asset in order to finance their war and put politically unreliable bankers in the North out of business. The Bonelatta “Big Bills”, as I’ll call them, arrived just when pro-war bankers needed reliable cash and there was little to be had for any banker. Lincoln-friendly bankers got piles—literally piles— of the Big Bills when they needed them to stay solvent.

The front of an 1869 “Rainbow” United States 100 Dollar note. ForeignCurrencyandCoin.com

Reverse of note pictured above.

Close up of the US$ 100 bill pictured above.

The above inscription reads:

THIS NOTE IS A LEGAL TENDER ITS FACE VALUE FOR ALL DEBTS PUBLIC and PRIVATE, EXCEPT DUTIES ON IMPORTS AND INTEREST ON THE PUBLIC DEBT. (Lincoln didn’t want foreign merchants paying him in these things, and of course he won’t print more bills like this to pay his creditors in London!)

Counterfeiting or Altering THIS NOTE, OR PASSING ANY COUNTERFEIT OR ALTERATION OF IT, OR HAVING POSSESSION and FALSE or COUNTERFEIT PLATE OR IMPRESSION OF IT, OR ANY PAPER MADE in IMITATION OF THE PAPER ON WHICH IT IS PRINTED, IS FELONY, AND IS PUNISHABLE BY $5000 FINE, OR 15 YEARS IMPRISONMENT at HARD LABOR or BOTH.

The above inscription is almost funny when one appreciates the level of hypocrisy behind it.

What Arabut Ludlow and Napoleon Bonaparte Latta were participating in was more than just organized crime, they played a key role in a scheme to take over Washington D.C. via the financial industry. While our Green County “elite” did the grubby work moving these Big Bills around, a far more elegant deception was unfolding on Wall Street via the First National Bank of the City of New York (FNBNYC).

The establishment of the FNBNYC is probably the most influential happening in the history of US banking, consequently important features of its founding aren’t talked about very much. In this post I owe much to the work of James Grant, author of Money of the Mind: Borrowing and Lending in America from the Civil War to Michael Milken.

FNBNYC’s founder, George Fisher Baker, was descended from a radical Quaker** family in New York state, the long-time fiefdom of those monarchist sex-slavers, the Livingston Clan. George F. Baker was born in 1840 and his father was a political creature of Samuel Sweezy Seward, who’d made his money in NY/NJ “land speculation”; organizing the guild of Orange County New York doctors; being a ‘shrewed investor’; and recognizing that “advancement depended on pleasing others”. Similar to the Livingstons, the Sewards were Black slave-owners who disliked Black slavery. Like Monroe’s ambitious Universalists, the Sewards invested in early childhood education.

In tying himself to Samuel Sweezy, Pa Baker became a functionary of the controllers of New York State finances, a.k.a. Livingston “aristocratic” business peers. Robert Livingston was busy building his NYC bordello empire when S.S. Seward was busy assuming the public face of NY politics— something the traitorous Livingstons shied away from in the aftermath of the Revolution. Families like the Bakers were looking for new patronage as their traditional Quaker dons crumbled in factional infighting over the 1830s-40s.

In light of the above, it’s not surprising that Pa Baker was able to nepotize a job for George Fisher Baker at the New York State Banking Department, remunerated at nearly ten times his previous private sector salary. This was just the beginning of lucrative things to come.

George Fisher used his government-affiliated post to become a financial intelligence and investing vehicle for his father: Pa Baker would send George money, George would invest it and send back intelligence. Some of these schemes were unethical even by Pa Baker’s standards. (See Money of the Mind, by James Grant.) Playing US government bonds was George’s particular specialty. In behaving this way, George Fisher Baker came to the attention of one of the USA’s most important, and most destitute-on-paper, anti-counterfeiting watchdogs, John Thompson.

John Thompson, the real architect of the global financial system minus Iran. He got his start running ‘extra-legal’ lottery schemes.

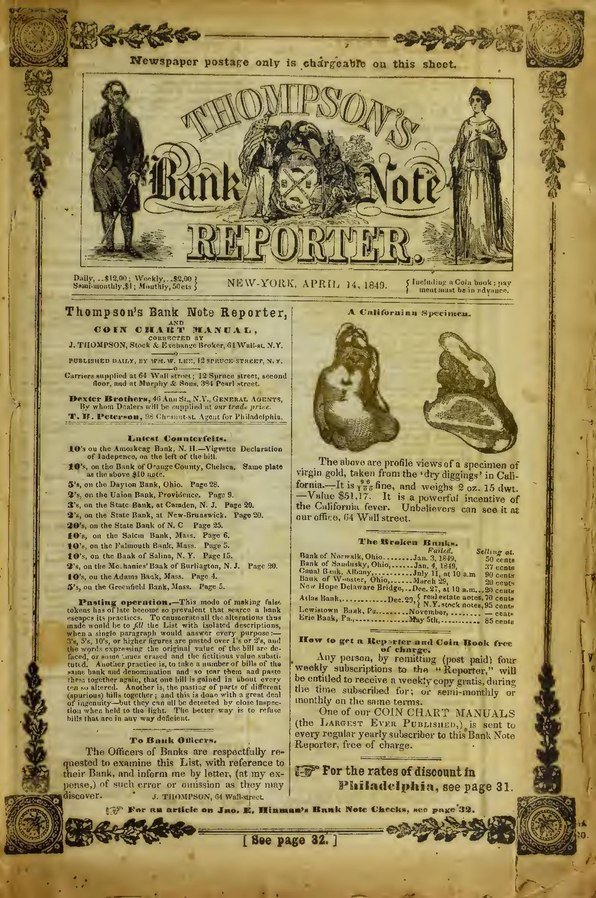

Thompson made his name by publishing Thompson’s Bank Note Reporter, the preeminent publication alerting US businessmen to which notes in circulation were fake and which weren’t. This was a hugely powerful and dangerous position for a publisher to be in. It was also a position fraught with temptation. Thompson went bankrupt during the Panic of 1857.

A cover page from Thompson’s Bank Note Reporter from before his bankruptcy.

Don’t let the bankruptcy fool you. Thompson was rich before his bankruptcy, let alone after the Civil War. He built the summer house below between 1853-58— heck, the 1857 bankruptcy may have helped him get this pile built for less. Such a maneuver certainly lowered costs for the Universalist Church in Monroe, which had similar “financing” troubles when it came to paying tradesmens’ bills and which was bought back cheap by parishioners after an initial liquidation.

While John Thompson was out of cash personally, he wasn’t out of connections. (His sons were not anything near bankrupt, they continued the Bank Note Reporter under “Thomson Brothers” ownership.) James Grant explains the situation: “At the outbreak of war (US Civil War 1860), John Thompson, though surely distracted by his own affairs, nonetheless was able to participate in the national debate over how to organize the banking system to serve the Union cause.”

John Thompson lobbied for the 1863 “National Currency Act”, an act which decreed that government-printed money would be used by banks as reserves instead of gold. What made this government-money so safe was that the Union would win and the government would repay its debts. Duh. Do you love Jefferson Davis?

The new “greenback” currency was strengthened in 1864 by a revision called the “National Banking Act”. (Remember that from Arabut Ludlow’s bank?) Under this 1864 revision, any bankers who didn’t buy Lincoln’s new government-printed money with their gold and continued issuing their own banknotes would be held personally liable, i.e. personally bankrupted. These are the days before corporations, readers. (Though not long before, ha!!)

The “National Banking Act” was not a good deal for bankers, compared to what they enjoyed under the individual states’ stewardship. “National” banks had to hold 25% of their deposits in “reserves” of greenbacks (there’s a war to finance) and these greenbacks couldn’t go into circulation. (This was a measure against inflation when greenbacks were being printed to pay for the war. Compare it to China, Russia, Japan holding US dollar reserves— a.k.a. US government debt— these days.) “National” banks were prohibited from circumventing this inflated “greenback” currency by lending against land and were heavily restricted in what they could invest in. N.B. this greenback was being even more heavily inflated via Monroe, WI counterfeiting networks than was admitted by official printing numbers from the “American Bank Note Company”.

Thompson’s sons were the first to apply for a banking charter in NYC under the 1863 Currency Act and their bank was the first to receive a charter there. (Why the sons? Thompson senior was a bankrupt and that didn’t smell good in the days before taxpayers picked up failed banker’s debts.) Grant on the Thomspson family’s role in this financial colonization scheme:

What distinguished the “greenback” from private-issue bank notes was that the government’s money was convertible into nothing. It was “legal tender” by force of law rather than by virtue of intrinsic value (a.k.a a healthy banking balance sheet with gold, or another non-counterfeitable commodity in reserve). As a check on the solvency of note-issuing banks (notes backed by greenbacks by force of law) Thompson had dispatched his sons in horse and buggy to present them (the correspondent banks) with their own notes. To redeem one’s notes (for a correspondent bank to offload greenbacks) was to pay gold coin for them (the correspondent bank would have to pay this gold to the government ultimately). A bank that was incapable (unwilling) of meeting this demand was, prima facie, insolvent, and Thompson would fry it in his paper and perhaps precipitate its closing. The National Currency Act was a force for financial uniformity. The risk it introduced was that the national finances would become uniformly unsound rather than only irregularly unsound, as in antebellum days.

So what did Thompson Sr. see in 17 year-old George Fisher Baker? Whatever Thompson saw, he saw it in the year he went bankrupt, and he invited young G. F. Baker to be a partner with him and his sons in the venture described above. Thompson gave Baker stock in “Thompson Brothers” far in excess of what Baker could buy with this investment capital of US$ 3000— Grant says Thompson offered Baker “as much of the new stock as he wanted; but Thompson would lend him the money”. :) This was a risk G. F.’s dad was willing to shoulder, ethical or not.

With the Thompson Bros’ newly-minted first charter for a “National” bank in New York City, the First National Bank of the City New York, opened its doors on July 22nd 1863 with a 23 year-old at its helm. Money-lending directly was not its goal, its goal was to shepherd the government debt security (bond) market. James Grant:

George F. Baker brought the asset of political pull to his job with the Thompsons. His father was an intimate of Secretary of State Seward; and Seward, it was expected, would bring the merits of the new bank to the attention of Secretary to the Treasury Salmon P. Chase.

Regular readers will remember Salmon P. Chase as the Ohio governor who sprung Joshua Miner from jail so he could start industrial-scale US treasury note forgery in the same city as the American Bank Note Co. of NYC. Arabut Ludlow’s “National” bank would be charted months after the Thompsons’. Chase did precisely what was “expected” and in 1864 the FNBNYC became ‘agent’ for the sale of the Union’s 5% bonds, in other words they were the first organization to profit from trading Lincoln’s I.O.U.’s.

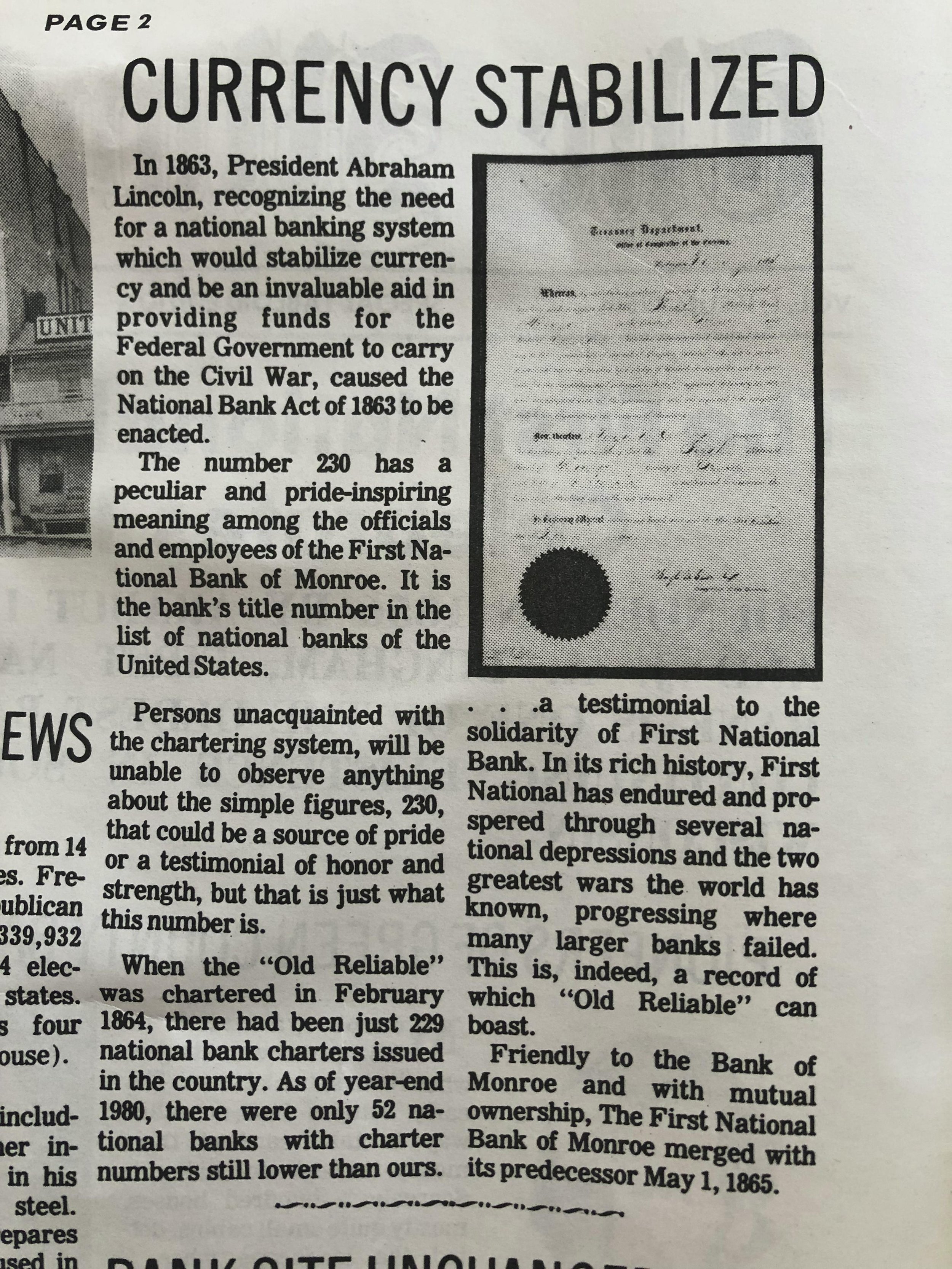

From a 1981 anniversary newspaper printed by Monroe’s First National Bank, titled “The Monroe Sentinel”.

From a 1981 anniversary newspaper printed by Monroe’s First National Bank, titled “The Monroe Sentinel”.

The state-charted banks of NY resisted this federal colonization. Thompson, Lincoln and Chase had to play hardball. The first move was to send a federal examiner named Charles A. Meigs to pump the reputation of the bank which, like the current FTX scandal, was staffed with an inexperienced youngster and executives like Ebenzer Scofield, who wore an impossible number of hats— yet profits grew “without precedent in the history of banking in the City of New York” according to Meigs.

How did FNBNYC do this? “In 1864, the directors of the First National Bank had resolved never to lend except against the collateral of U.S. government bonds.” FNBNYC exploited its relationship to “capital” printed by Lincoln to lend to smaller banks (without as much political pull) in the hinterlands. Hence the eagerness of Ludow and Bingham documented above. Grant quotes Meigs:

For instance, the First had cultivated business relationships with new national banks [like Arabut Ludlow’s in Green County, WI] “in all parts of the United States and in fact it may well be called a Manufactory of National Banks.”

Meigs went on to say:

“Almost all of their Discounted Paper, they have discounted for their Country Correspondents, with the endorsement of the Bank from whom it was discounted, and, as a consequence, losses in this line are of very rare occurrence.”

Translated, this means that when “National” banks outside NYC made bad loans, the Thompson Brothers could get out their horse and buggy filled with newly printed “Currency” to make up the difference… or they could just send a Bonelatta agent with those otherwise unpassable Big Bills. These inflationary Bonelatta bills would, of course, be off-books. Phew!

We are blessed to have an account of how FNBNYC’s piles of “Currency” made it to Lincoln’s “correspondent” banks at the right time. In Meigs’ own words:

I will cite the case of their correspondent— “the Rochester Savings Bank” with $8 Million Deposits— very sound— but upon whom a run was commenced about 10 days since.

Two of the Trustees at once applied to the 1st National Bank for help— having 2 Million of U.S. and other good Bonds, in their hands.

The Bank loaned them $500,000 Currency, on the spot, and hurried it to Rochester, by Express.

Within a day or two $600,000 more was loaned them— in Currency— and hurried to Rochester— to the rescue of a solvent Institution! and a virtual agreement made to make the amount up to $2 Million, if needed— Securities to this amount being left in their hands…

Now all this was done so quietly that the world knew not from whence the mighty ‘help’ came.

It is a great “feather in their cap” and I commend them for their energy of action at a time of most urgent need, and would offset this against some of their “Brokerage” business, as there is not a single Bank in our City who would or could have helped a country correspondent to such gigantic figures, and on such short notice!

Can you wonder that this Institution gets such enormous Country Bank Deposits when this is the way they will come to the rescue?

Profiting from uncertainty around their satellite banks, from a never-fail position themselves, became the primary source of business for the FNBNYC. Grant:

In fat times, it (FNBNYC) accepted the deposits of country banks and paid them a small rate of interest, relending at a higher rate. In lean times, it would anticipate the role of the Federal Reserve System, standing ready to lend to a correspondent in trouble, as it had in 1877.

While federal examiner Meigs couldn’t say enough good things about the FNBNYC business model, he struggled to say anything good about its accounting practices, which were not industry standard for the day. In fact, FNBNYC had funny book-keeping methods which Meigs had to explain away: “The character of their accounts is peculiar, but it is specially adapted to the nature of the business in which they are engaged.” Examples provided by Grant are “junk bond”-like bankruptcy-linked securities which sound similar the real estate liquidation scams run by early film investors out of Chicago (see Grant, page 51). (Al Capone got his first whore house premises this way.) The real danger, of course, was having to account for bills on the books of satellite “National” banks which should not have been there according to Chase’s Treasury.

In effect, the National Bank Act of 1864 was the first way taxpayers were footed with the bill for “National” bankers’ poor banking decisions. After all, Uncle Sam never fails because you and I are alive to tax— at least to tax enough to cover some of the interest. But what sort of business climate does that make for bankers who didn’t bend over for Lincoln? They lost a big chunk of their business (issuing their own bills) and had to bear financial responsibility for their banking failures. It was just a matter of time before “nature” took its course— more on that below.

So what did the Thompsons’ do with all this “Currency”? Buy more favors around Washington D.C.! Kinda like the Chinese 150 years later.

A favorite investment of the First [FNBNYC] was the District of Columbia. “In looking over their affairs,” wrote Meigs to the home office in March 1873 [when Grant had gently closed the Bonelattas], “I find that over $6,500,000 of the bonds for the grading, paving, services. of your City has passed thro [sic] the hands of this Institution during the past two years!”

What sealed the deal for FNBNYC was the Panic of 1873, which bankrupted its strongest competition. (By the late 1870s FNBNYC was one of the leading banks in the country.) This panic was started by the Hapsburg’s shoddy railway business partnerships with creepy British investors and the Rothschilds— I wrote about that with respect to the slave-trade Ludwig Bahn here. The ripple effect of this liberal banking failure on other overheated rail investments— like Jay Cooke’s Northern Pacific Railway— undid bankers whose teat wasn’t solely the US government. As one of the few big banks left standing (thank you, Franz Joseph!) FNBNYC was set to become “Citigroup” owner of “Citibank” in 1955. Most of the big names in American banking owe their success to being on the right side of “National” politics during the Civil War.

It gets even better though, readers, because once the Thompson clan had set up thirty-seven year old Baker as the sole face of FNBNYC in 1877, they went on to found Chase National, now JP Morgan Chase. Half of the “Big Four”, which are “too big to fail”, were founded by Thompson!

As I wrote about in my previous counterfeiting post, Chase National was named after the founder of the feast, Salmon P. Chase. Citigroup owns a really cool skyscraper now, and they helped Arabut Ludlow build his fancy house on the outskirts of Monroe, WI. Maybe I should say that Arabut Ludlow helped them build their skyscraper, because without those shady $500 bills none of this glory would be possible…

The history of banking in the USA is largely the history of how things kept getting sweeter for favored “National Banks”. On December 23, 1913, when President Wilson signed the “Federal Reserve Act” in the rush up to Christmas, that sweetness reached a new apogee. Members of the Jekyll Island Club, which included Early Film king-maker Otto Kahn’s partner Paul Warburg as well as George Fisher Baker, designed this act with the finances of warring Europe in their cross-hairs. It was truly “Baker weather” as club-members dubbed good times for profit.

And our little town in Southern Wisconsin was a key reason for those blue Christmas skies!

** That Baker came from a Quaker family, and a radical New England Quaker family at that, is hinted at by Grant, but for some reason seems to be something biographers don’t like to stress. That the Bakers were Quakers is evidenced by Baker’s father attendance at the local “Meeting”, as well as by the marriage ceremony of subsequent Bakers and the business partners chosen by George Fisher Baker.