Performers, Prize Fighters and Pimps: David Belasco

You can’t get far in the world of Early Film without bumping into the name of David Belasco. He was not a film-man himself, but he controlled the talent which headlined Early Film: D. W. Griffith, Cecil B. DeMille and Mary Pickford to name three. Belasco found himself in this position because 1) Galician “White Slave Trade” networks used traveling theatrical troupes as cover, which contributed to 2) US theaters being controlled through monopolies, and finally 3) because British “active measures” operatives using the US theater industry decided to employ Belasco’s bosses, the Frohman Brothers.

David Belasco came from a Sephardic organized crime family at the heart of London’s theatrical community— the community so well represented by criminal lawyer Sir George Henry Lewis. London was a hub in a global prostitution network that was controlled out of Hungary until after the establishment of the “Dual Monarchy” in 1867, i.e. Austria-Hungary: the Austrian Empire minus its Prussian influence and the “-Hungary” half being largely autonomous. Following that seismic political shift, control of the prostitution network slid to Galicia, a Polish part of Austria-Hungary which was still under Hapsburg control. Austro-Hungarian Police identified international troupes of performance artists— Vaudville-like acts— as a primary vector for White Slaving. [See N. Wingfield, The World of Prostitution in Imperial Austria.] At the glamorous pinnacle of the trade were product like Sarah Bernhardt or ‘La Belle Otero’, but most victims could expect to be sick, in debt and unemployed by 35 (or dead).

Whomever controlled the flow of traveling theatrical troupes controlled a very lucrative slice of the White Slave Trade. English-speaking talent, like that out of London, was at a premium for the American theater market.

By 1896 stateside, a handful of mostly German-Jewish entrepreneurs, including one junior partner David Belasco, controlled the key theaters on routes connecting urban centers. Performers were told where and when to play. This monopoly was called the “Theatrical Syndicate” and it controlled over 90% of the “better” theater venues at its heyday (1896-1911).

The only way to break the Theatrical Syndicate’s power from below was to buy up performers’ contracts and starve the syndicate of talent: control the trafficking stream rather than the venue. David Belasco was in on the ground floor of this development too, with the help of the impoverished Shubert Brothers (originally surnamed “Schubart”, a family of German Jews in Russian Lithuania), who he’d groomed from a young age. Somehow the Shubert Organization found financing to become the new monopoly. However, in 1905 when their leader Sam Shubert was killed in a freak railway accident, which happened surprisingly often with this crowd, the Shuberts went into partnership with the Theatrical Syndicate. The real end of the Syndicate came in that magic year 1916, the same year Josephus Daniels shut down the whore-houses; Pancho Villa and D. W. Griffith fell from favor; and Col. Fayban became an anglophile. Belasco’s “Shubert Brothers” and Belasco’s “Early Film” talent, often with Commonwealth accents, would march boldly ahead with the war effort. And of course Sir George Lewis’s nephew-in-law Otto Kahn became Early Film’s financial king-maker.

Our Boys in France Tobacco Fund: “Mary Pickford getting tobacco and cigarettes for the soldiers. In addition to supplying her own adopted contingents, Miss Pickford has sent thousands of smokes to the boys in the trenches. The others in the picture are Norman Kerry, in uniform; Marshall Neilan, her director and Theodore Roberts." (1918) Wisconsin Historical Society. Please see my post on Cigarettes and the White Slave Trade.

How did any of this come to be? Certainly the traditions of the European stage established slaving/prostitution/theatricals as closely-related professions. No family history exemplifies this better than that of London’s Belascos.

With thanks to Lynn Lewis’s work via Ancestry.com and Alfred "Ed Moch" Cota of Geni.com

With their roots in the ports of Seville and Livorno, the Belascos typify a social phenomenon which historian Lois C. Dubin identified as “port Jews” (a play on “court Jews”). The roots of this phenomenon lay in Jewish merchants’ role in the Spanish Empire.

The expulsion of Jews from Spain which began around 1492 displaced a fraction of Spain and Portugal’s Jewish population. Many fled East to places like Poland, while a large contingent moved to South America, where they swelled the ranks of ‘conquestadors’ and developed the colonial economy, including the “Atlantic Trade” which extended the preexisting African Slave Trade to the New World. Spanish and Portuguese colonial administration depended on this community both for local colonial administration and repatriating taxes and dividends to Latin Europe.

Spain’s colonial administration was remarkably corrupt and this weakness was exploited by Spain’s adversaries, most famously Oliver Cromwell and his “Grand Design” partnership with politically ostracized Jews in Spanish possessions like Jamaica. Competing families like the Medici in Italy, the Stuarts and eventually the Hapsburgs set up designated ports, sometimes called “free ports”, to encourage illegal trade and piracy which preyed on the failure of Spanish colonial governance. As a Europe-wide phenonmenon, this legitimization of organized crime, indeed it was state-sponsored organized crime, fueled the rise of rich, urban middle classes with little connection to the indigenous populations wherever they settled.

“Port Jews” were a prominent fraction of this new middle class and provided important trading links with the Muslim World, where Jewish communities also congregated in ports and were prominent in both the Black and White Slave trades. Probably the most famous of these pirate/merchants/slavers is Rabbi Samuel Pallache whose biography A Man of Three Worlds, by Mercedes García-Arenal and Gerard Wiegers, has been translated into English. Pallache, under a Moroccan flag, would raid coastal European towns and sell their people into the African and Muslim world. Pallache slaved with Dutch and English protection out of base-ports at London and Amsterdam.

Rembrandt van Rijn and Workshop (Probably Govaert Flinck), “Man in Oriental Costume”, c. 1635. Believed to be a portait of Rabbi Pallache.

These “Port Jews” lived in a parallel world to their Christian peers in Europe. Potentates like Maria Theresa gave legal protection to their overseas illegal activities as long as those illegal activities served her interests too. She set up Trieste as a “free port” for this reason and gave the Jewish community there a large degree of self-governance. Indeed, access to Trieste’s Jewish quarter was dictated by Jewish leaders and Austrian police couldn’t enter there until organized crime became so debilitating in the city that a new joint-governance partnership had to be arranged. [See Dubin.] Maria Theresa established these policies because she wanted to copy the Medici’s mercantile success at Livorno, where a similar situation existed. Livorno, or ‘Leghorn’ in English, became known as “the Algiers of Christendom” under these pro-slavery, pro-crime policies. Of course the situation in New World ports like “Port Royal” in Jamaica is well known.

1692 Earthquake-caused building destruction (red) of Port Royal, Jamaica from the eyewitness account of Rev. Emmanuel Heath, courtesy of Port Royal Jamaica History. An enlightening contemporary account of Port Royal and the earthquake recorded by Col. A. B. Ellis states:

“The houses from the Jews' street end to the breastwork were all shak'd down save only eight or ten that remained from the balcony upwards above water. And as soon as the violent earthquake was over, the watermen and sailors did not stick to plunder those houses; and in the time of their plunder one or two of them fell upon their heads by a second earthquake, where they were lost. . . .”

Smithsonian Magazine, July 7 2016: “If Jamaica were to become a second tropical Jewish homeland (after Florida, of course), the obvious capital would be Port Royal, which sits at the end of a long isthmus across from Kingston. In the 17th century it was the center of Jewish life on the island, with a synagogue and a central thoroughfare called Jews Street, until it was destroyed in 1692 by an earthquake.”

In the 1980s through 1990 Texas A&M University financed an extensive underwater archeological study of what remains of 17th century Port Royal. The synagogue— the first in Jamaica— and the Court House are the only buildings marked on the street immediately above “LIME STREET”. Although the damage done around “Jews Street” features prominently in eye-witness accounts, and the synagogue is a key map-marker, A&M didn’t discuss it much in their analysis and “Jews Street” is not marked on any map I could find. “Jews Streets” grew in more than one New World city.

Images of a New World “Jews Street” in Recife, Brazil. The black masses on the street are people.

From Siger.org, the website of Harrie Teunissen and his partner John Steegh , who are map-collectors from Leiden in Holland:

“Here, on contemporary watercolors by Zacharias Wagener, you see the slave market in Jews Street, Recife, and house slaves transporting a Portuguese lady. Research on the auctions in Pernambuco shows that the purchase of slaves by Jews rises from 21% for 1637/40 (an average of 127 slaves a year) to almost 50% for 1641/44 (that’s 341 slaves a year). The slaves are often sold on credit, later to be paid in raw sugar. The dominancy of Jews is shown also by a ruse from Catholic and Protestant slave traders who in 1644 try to organize a slave auction on a Jewish holiday. But the government intervenes and the plot fails. When the mass of slave workers on modern plantations and sugar mills outnumber the familiar house slaves, racial notions transform old Jewish precepts. From 1647 on, ‘Jewish mulattos and blacks’ are to be buried on a separate section of the Jewish cemetery. Growing separation within the community is not limited to Jews. Protestant masters prevented already in 1636 baptized slaves to participate in their church services, they should attend special services. And after 1649 the Jewish congregation of Recife fines the Jewish master who circumcises his slave so he can become part of his household, as was the custom based on Genesis 17:12/13 and Exodus 12:44. Henceforth circumcision is allowed only after manumission and conversion to Judaism.”

A core feature of the “Port Jew” phenomenon was that the communities were lead by powerful “shtadlanut” families who had control over a mass of very transient lower-status Jews, whose upkeep was subsidized by a combination of Jewish and Christian-taxpayer charity. I discus this shtadlanut situation in my post on Sir George Lewis and Otto Kahn in the nascent ‘intelligence community’. These wandering masses formed the smuggling, espionage and trafficking networks which facilitated organized crime.

If you study the Belasco family tree above, you’ll see that most of David’s relatives on the female side came from Seville, an important Spanish port for New World and African goods, or the infamous Livorno. We know little about the male line of David’s ancestors: this may be because no one has looked in the right place yet, or it may be that the “Belasco” clan were too transient and low-status to be caught by synagogue records. According to the Dictionary of American Family Names (2nd edition, 2022), “Belasco” is a surname from the Basque (northern coastal Spanish) region: “Castilianized form of Belasko from the Basque personal name Belasko composed of the elements bela ‘raven’ + the diminutive suffix -sk”.

What we can say with certainty is that these Latin-world immigrants found succor in London a few decades after the arrival of the Hanoverians in 1714. We can also say that the Belascos thrived in London’s underground world of prize fighting and prostitution. By far the best information on “The Fighting Belascos”— David’s grandfather and two great uncles— comes from Gwen MacDougall in her article of the same name in Shemot, The Journal of the Jewish Genealogical Society of Great Britain March, 2003 from which the following quotations are taken. David Belasco’s grandfather was the second of three pugilist brothers: Abraham (1796-1859), Israel (1798-1866) and Samuel Belasco (1802-1875).

Of the three Belascos, Aby was the most famous, described by Egan [Pierce Egan, his biographer] as “a boxer of superior talent, amast of the science, having the advantage of youth on his side not being more than 20 years of age, not deficient in strength, of an athletic make, a penetrating eye and, in the ring, full of life and activity”. Aby became a professional boxer in 1817 and quickly established his popularity with the fans. An interesting comment by Egan indicates that his occupation in his earliest years was as an orange boy. He was apparently in the process of selling oranges to the spectators when he was unexpectedly called upon to enter the ring at Moulsey Hurst on 3 April 1817...”

Selling oranges was also a typical cover for prostitution, made famous by the prostitute mistress of Charles II, Nell Gwyn. Orange-selling gave Aby the opportunity to attempt armed robbery on his customers, which landed him in jail the first time (1815). But from there out boxing and pimping were more his thing:

His [Aby Belasco’s] ventures into crime and prostitution brought him as much publicity as his boxing. In 1825 Aby married Eliza Whaite with whom he had been living and had a son, Joseph, born in 1823. At this time the couple were living in the Strand. [Famous for its publishing outlets.] In 1829 there were a number of robberies at the brothel he was running in the White Hart Yard; two girls were accused of stealing 15 sovereigns…

He was also charged with running a brothel in Long Acre. A few sessions earlier his wife was sentenced to 12 months’ imprisonment… Information about the Belascos’ criminal activities comes from several sources. The criminal records held at Guildhall gave information about offences which had taken place within the City including court sessions at the Old Bailey [where the Lewises reigned by at least 1830]….

Other information contained in the newspaper articles mention that Belasco had a “gang”. In yet another occasion we are told he assisted the police to make arrests. In total Aby Belasco appeared in court on at least 20 occasions for assault or offenses associated with prostitution.

Todd Endelman in his Georgian Jews of England 1714-1830 describes Aby as “a keeper of low gambling houses, night houses, supper rooms, and such like resorts of midnight and morning debauchery”.

Joseph Abraham Belasco— David’s great-grandfather— was a fruit merchant which is an occupation with strange associations Stateside too. David’s grandpa, Israel Joseph, was also a famous prize-fighter but left the ring to take over the fruit concern and start his own bordello by 1822. Israel Joseph ran his business out of Covent Garden, the famous theatrical district.

The youngest pugilist brother, Samuel, got on the wrong side of the Theater Mob and his brother Aby turned him in to authorities, which eventually lead to Samuel’s “transportation” to the notorious Van Dieman’s Land (now Tasmania):

Samuel, the youngest of the three Belascos, was something of a mystery. Little is known about his boxing career but like his brothers he engaged in criminal activities. An article appeared in The Times on 26 May 1825 which described how Samuel was seen pick pocketing. It was alleged he took several sovereigns and a silver pencil-case from a Mr Lee. In a skirmish with the police, Aby claimed they kicked and beat his brother shamefully and as he was not prepared to stand by and watch, he tried to free his brother from their clutches. In his defence, Aby said that he had not spoken to his brother for some time since an incident in which Samuel had stolen money from the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden. It appeared that Aby handed his brother over to the authorities and as a result Samuel served three months in a Middlesex “house of correction”.

Readers may remember that the Theatre Royal of Covent Garden was the very place the Galician Gang made their London debut as a proto- “Pinkerton Detective Agency” thugs. The above strongly suggests Aby Belasco was among the boxing “toughs” who were paid to beat protestors at the theater.

These ‘Pinkertonesque’ incentives probably explain why Londoners associated Jewish pugilists with violence outside the ring. Endelman:

They [Jewish prize fighters] were stigmatized as ruffians and brutes. Knapp and Baldwin’s New Newgate Calendar (1809-10) remarked that “of late years” the Jews were becoming “the bullies of the people of London.” “The disgraceful practice of pugilism, revived by Mendoza [Daniel Mendoza, 1763-1836] on their part, has greatly increased as well their depredations as their audacity.” Marianne Thornton recalled that when her father, an important member of the Clapham Sect [evangelical Anglican abolitionists], was once campaigning for Parliament in Southwark, “Mendoza the Jew boxer” was part of the mob demonstrating against him. He kept shaking his fist at Thornton and crying “No popery! No popery!” (Thornton was in favor of Catholic emancipation; Mendoza in all likelihood had been hired to raise a clamor.)

[Aby Belasco would marry David Mendoza’s widow as his third wife.]

It was not just Belasco men who were involved with prostitution, however. A Rachel Belasco ran a brothel with her brother-in-law/lover/husband Emanuel Simmons (they also sold lemons). According to Madame Rachel biographer Helen Rappaport, one Mary Belasco bought London’s most high-class brothel from Kate Hamilton. Apparently Mary Belasco was an “old friend” of fellow whore-house operator “Madame Rachel” Levinson, whose blackmail operation was protected by Sir George Lewis. (See Beautiful for Ever, p. 104.) These Belasco whore-houses went under the names of “night cafe” or “supper rooms” and gambling was ubiquitous.

Identifying women is a tricky thing in the organized sex trade. Establishing the exact familial relationship between Rachel, Mary and David Belasco is difficult, but pimping was done on a family-network basis so it’s likely familial relationships existed. It was typical for pimps to have more than one informal ‘wife’ on the go at any given time, this ‘wife’ would take the fall if the prostitution operation got busted. Endelman notes that by the 1750s in London, Jewish immigrant men cohabiting with non-Jewish women “became a frequent occurrence”. The demographics of the prostitutes caught up in the “Galician Network” are not well researched in academic circles.

A photograph of young David Belasco.

To paraphrase Charles van Onselen, London’s theater district prostitution scene was the “shabby nest” from which David Belasco sprung. David first comes to attention as a teen in the port of San Fransisco, California, where Charles Frohman owned a chain of West Coast theaters. The environment in San Fransisco was similar to that of London’s Covent Garden. What made David’s career was being noticed by the Frohman Brothers, who in turn were hired by an evangelical Church of England (CoE) missionary outfit intent on proselytizing in the USA via New York City’s Madison Square Theater.

The history of the CoE outside England is one of religion being exploited for espionage purposes. We first bumped into this with the Livingston family and their flirtation with Presbyterianism. From the earliest days in Colonial America, the Church of England was used as a political bulwark against Catholic France and Spain, often in partnership with a German Protestant sect called “Pietists”. Together, Pietists and CoE men printed German-language bibles for US distribution in order to prevent places like Maryland turning Catholic. This must be among the earliest “active measures” operations carried out on US soil, and it was done under the auspices of “The Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge”, a cut-out designed especially for the purpose. Later, as anti-slavery became important to the British for fighting France, abolitionism found a home in Anglophile US churches, like the one run by Virginia Whittingham’s ancestor, Washington D.C.’s Civil-War-era Episcopal Bishop William Rollinson Whittingham. (“Episcopal” is what the CoE in the USA called itself after the rout of 1783, when the Quakers fled NYC with the “Jackson Whites” et alia.)

The outfit which hired the Frohmans was named the Church Society, an evangelical Anglican organization founded to combat Catholicizing tendencies inside the Church of England in England. The Catholicizing trend became popular in the early 1890s and remained potent until the shock of WWI. An example of this trend was Oscar Wilde’s death bed conversion to Catholicism, and typically it was the “decadent” type of English writer of whom Vienna’s Ringstrasse would approve who ‘jumped ship’ to “popery”. (Walter Pater, a member of Sir George Lewis’s set, was a notable proponent of this trend for Catholic religious pageantry.) The struggle between Catholic and Protestant beliefs in England has always had intense political undertones.

In New York City, the Church Society was represented by the editors of their flagship journal The Churchman, Rev. Dr. George Mallory and his brother, who also bankrolled the publication. Rev. Mallory wanted to use the Madison Square Theater to broadcast a Churchman-approved message and they employed a truly visionary playwright/director named Steele Mackaye to this end. As promoters they hired the Frohman Clan.

Daniel Frohman

Charles Frohman, who died on the Lusitania.

Why did the Church Society hire the Frohmans? It’s worth mentioning that prior to the hire, Charles Frohman “got in touch with the right people” in London to get Crown Prince Edward and his mistress Lillie Langtry to attend a minstrel (as in “blackface”) show Charles had taken on tour there. [See the Marcosson biography of Charles, p 76.] These “right people” couldn’t have been far from Edward’s fixer, Sir George Lewis, lawyer to London’s Jewish entertainers. (Lillie Langtry was Britain’s first “society woman” to go on stage, and was a friend of Oscar Wilde, Lord Rothschild, and Sir Ernest Cassell, whom regular readers know from their White Slave Trade work, or their connections with Vienna’s Ringstrasse.)

Lillie Langtry, as painted by George Frank Miles, 1884. Langtry was a “muse” for Oscar Wilde and his set, which wasn’t always a fun job:

“The friendship between Lillie and Oscar Wilde came to an end when the relationship became too intense. Lillie would find Oscar curled up asleep on her doorstep: Mr. Langtry, returning unusually late, put an end to his poetic dreams by tripping over him. He presented her with a white, vellum-bound copy of his poem `The New Helen' with a dedication `To Helen, formerly of Troy, now of London' and generally found him too persistent in hanging round the house or running about after me elsewhere.(2) Upset after a rude remark that she had made to him, Oscar was led away in tears from the stalls of the theatre by his friend [George] Frank Miles when he noticed her in her box.”

There was probably more to the Church Society’s choice than initially meets the eye, however. British spooks had a habit of going to German agents for US-focused services. Since the reign of Joseph I of Austria (1705-11), London had been a locus for German-funded propaganda via the indigenous publishing industry. The Pietist/Church of England undertaking I described above was the earliest of such ventures I’ve found, but the practice reached new heights on the eve of the French Revolution. One of the most active sponsors of such literary propaganda was the Landgrave of Hesse-Darmstadt, Louis IX.

Louis IX of Hesse Darmstadt funded a lot of revolutionary enlightenment propaganda through his unstable spymaster Johann Heinrich Merck. Apparently, with the ascension of Charles III of England, Louis IX is the most recent common ancestor of all current hereditary European monarchs: a sort of Y-chromosomal Adam Kadmon.

The Frohmans were a Jewish family from Darmstadt, home-base for Louis IX’s spymaster Johann Heinrich Merck and his 1773-1790 soft-power offensive called the “Volkaufklarung”. The “Folk Enlightenment” program was an engine for the ideologies which birthed the French Revolution. This program was a propaganda undertaking of world-wide significance, perhaps the first whereby literature, theater, scholarship and organized crime networks were coordinated in multiple foreign countries to promote the destabilizing politics of the landgrave, Merck’s ambitious employer.

The Volkaufklarung “active measures” networks Merck established long outlived him and cemented a centuries-long tradition of German espionage in London via the publishing industry. Merck’s fame was widespread in the German-speaking world, so much so that in the 1860s wannabe Ignaz “Paddington” Pollacky (a Sir George Lewis client and Hungarian slaving habitue) sold himself to Yankee diplomats as a Merck-successor. To give readers a sense of J. H. Merck’s culture-shaping achievement: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and the Brentano literary dynasty are Merck’s creations. The British John Murray publishing dynasty got its start publishing works by Merck’s ‘literary stars’.

A fanatical supporter of the revolution in France, Johann Heinrich Merck was a deeply driven and deeply troubled man who died in an unlikely fashion after the ascension of Louis IX’s unsympathetic successor, Louis I Grand Duke of Hesse.

By the 1850s the consequences of Merck’s irresponsible scheming had reached American shores. One of the Brentano offspring opened a bookstore in New York City, and ten years later the Frohman patriarch opened a cigar store next door. Together this Brentano-Frohman axis became NYC’s clearing house for global theatrical information, as well as for the illicit trade in “theater passes”, the abuse of which sparked the creation of The Friars Club.

Prior to his Brentano undertaking, the elder Frohman used the Stateside “Turner Hall” (Turnverein) network to stage old Goethe-approved amateur theatricals (i.e. Schiller) in Midwestern German-speaking communities. (Later in life Goethe took on a similar role in Weimar as Merck had taken in Darmstadt, but Goethe’s tenure as spymaster was marked by a more ‘reactionary’, conservative type of liberalism.) Elder Frohman’s' ‘Turner Hall’-style theatrics were conducted in Ohio, the Republican Party stronghold and capital of the US Jewish community at this time.

In the German states during the Revolution of 1848, some turnverein members sided with factions who unsuccessfully revolted against the monarchy, and they were forced to leave the country. Turnvereins were subsequently established by such émigrés in other countries, notably the United States, at Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1848, where the organization now called the American Turners was founded.

The Turner network was an highly-organized, German-language gymnastics association which back in Europe doubled as a militia or police force in times of state-failure. The Turnverein organization was closely shepherded by Hapsburg/Hohenzollern police networks following the demise of the 1848 revolutions. (The Turnverein’s predecessor organization, “Vater Jahn’s” Turnkunst brotherhood, had actually become an extra-governmental organization augmented by sympathetic members of Prussia’s military police during the state-failures which followed the Napoleonic Invasion and subsequently acted as a police informant network.) Monroe still has its Turner Hall and the old ‘48’er’ politics lived on in the likes of local painter Carl Marty Sr. who, along with Arabut Ludlow’s sons, organized the rebuilding of the Hall after a fire destroyed the original in 1935.

Monroe’s 1935 Turner Hall. When the original Turner Hall burned, local painter Carl Marty networked with Arabut Ludlow’s boys to have this Swiss-style structure built.

Before the ‘Church Society’— which was almost certainly a British Intelligence outfit— hired the Frohman boys, they followed in their father’s footsteps by hard-scrabbling around German Intelligence’s organized-crime edges. This included abortive attempts at theatrical management using the same Turner Hall network as a venue of last resort for under-cuting competing acts. In doing so, the Frohman boys engaged in typical pre-Hollywood behavior. Charles Frohman met Abraham Lincoln Erlanger, Marc Klaw, Al Hayman and David Belasco— all future Theatrical Syndicate and/or Zeigfeld investors— working this class of venues with his minstrel show or other attractions.

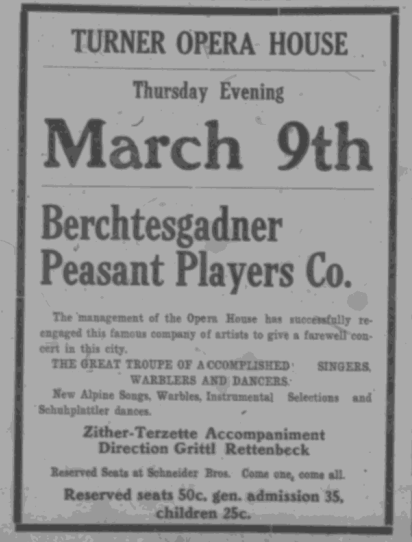

Monroe, WI’s Turner Hall served as an alternate venue for acts which didn’t get play at the Crystal Theater or the Princess. For instance, here is a March 9, 1910 ad for a German traveling musical act at the “Turner Opera House”, i.e. the Turnverein hall. By “warbles” they probably mean yodeling— the Monroe Evening Times’ editor was always an English-American.

Monroe’s Turner Opera would later give D. W. Griffith’s masterwork The Birth of A Nation a playing-venue when the Goetz/Ludlow theater didn’t play it. Turner Halls provided an important independent alternative to the big theater monopolies.

The Church Society’s Madison Square Theater gave the Frohmans the leg-up they needed to eventually form The Theatrical Syndicate. It was the “Hazel Kirk” play from Steele Mackay which gave the brothers the money and momentum to set up a well-organized touring company to capitalize on the play’s success outside of New York City. This one touring company blossomed into 14 separate companies, scores of underling booking agents, and a yearly budget of US$ 100,000 for poster-printing alone. The Frohmans hired young David Belasco to write plays and manage the stage, while they tapped lawyer Marc Klaw to go after pirates of their plays. The Church Society didn’t do things by half measures.

Beyond the overseas-CoE connection I described, there are other aspects of Charles Frohman’s career that suggest British intelligence sponsorship, these are 1) his travel habits and business method, 2) his friendship with J. M Barrie and finally 3) the Joan of Arc incident.

Charles Frohman built on the Madison Square reputation by organizing touring companies for other influential NYC theaters, which were often staffed with English actors. Charles began annual trips to London shortly after the “Hazel Kirk” success, and branched out into his own theatrical management business with Al Hayman, another Church Society acquaintance. Charles’ modus operandi was to select plays which were successful in England and recycle them in the USA. This opened up a life-long friendship/business partnership with the misunderstood playwright J. M. Barrie, of Peter Pan fame. Charles also set up his own “star system” , beginning with actor John Drew, which “brought about a revolution in theatrical conduct”. Charles Frohman wanted mass media stars in the manner of Empress Sisi:

Excerpt from the Marcosson/Daniel Frohman biography of Charles, 1916.

Another Frohman star, Maude Adams, cast in J. M Barrie’s play Peter Pan, which is about narcissistic abuse. J. M Barrie himself was a pedophile and had a highly controlling personality, not uncommon characteristics among the Galician Network. Image from the Marcosson/Daniel Frohman biography of Charles, 1916.

J. M. Barrie is famous for his child-inspired writing, but in real life he was an extremely well connected member of Imperial Britain’s elite, whose cricket team, the “Allahakbarries” read like an intersection between London’s publishing industry and the War Office: a staggering number of his players would take up service as war propagandists for the final imperial wars, some even as war propagandists working in the USA. Someone like Barrie did not chose business partners lightly.

Finally we come to one of the most telling episodes in Frohman’s professional life. For no publicly apparent reason, Charles Frohman used his theater business to snub Kaiser Wilhelm in the wake of the 1909 Franco-Prussian rapprochement treaty over the earlier Moroccan Crisis. This episode only makes sense when Frohman is viewed as a creature of British intel.

In 1905, the Kaiser Wilhelm II had offended French interests by supporting independence for Morocco, and had been forced to back down by British interference on France’s behalf. Conflict between members of the Triple Alliance and Triple Entente, which would ultimately lead to the First World War, was heightened. Over the next few years this tiff boiled on slowly, and the aforementioned 1909 treaty was signed. Frohman sent the proceeds to his production of Schiller’s Joan of Arc— about the French maiden who pulls victory from defeat— to Harvard University for a German library:

Charles Frohman would sink with the Lusitania. Excerpt from the Marcosson/Daniel Frohman biography of Charles, 1916.

I’ve taken the time to detail the Church Association, Barrie and Morocco connections because they evidence a pattern of British patronage for the Frohman clan, who in turn patronized David Belasco stateside. Bearing this patronage in mind, I’d like to turn our attention back to 1896 and the founding of the Theatrical Syndicate, which I’m not convinced was controlled by the British even though Frohman spearheaded it.

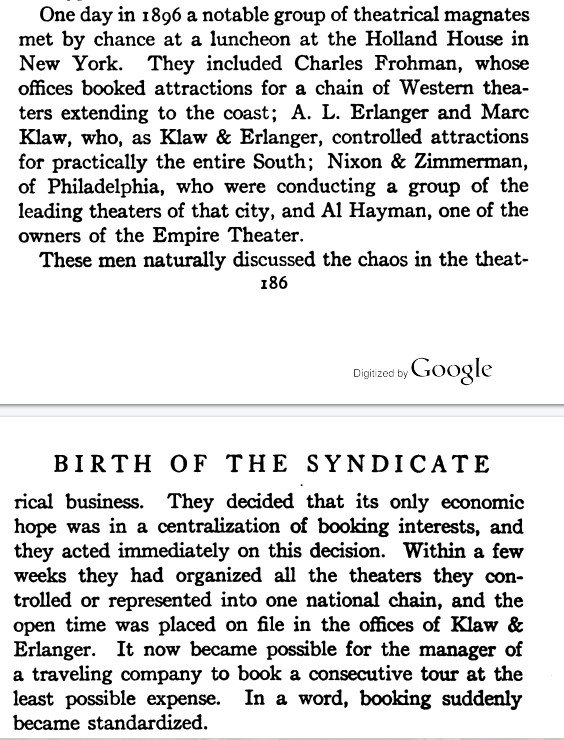

The Theater Syndicate was a monopoly which managed the vast majority of theater booking in the United States via controlling the theaters along routes to major metropolitan centers. (They didn’t own everything, they controlled everything by owning strategic smaller-town theater venues.) Charles Frohman’s monopolistic partners were almost all German-Jewish men he’d met working with the Church Society, or before while he was hard-scrabbling around Turner Halls. The men who seem out of place here are Nixon & Zimmerman of Philadelphia. Here’s a short account of how things went down:

From the Marcosson biography. Holland House no longer exists, but it was a 1890s-constructed New York City hotel at 274–276 Fifth Avenue, designed to be a replica of the famous Holland House in London, new seat of the “Fifth Earl Ilchester”, who’d just bought it in 1874.

Henry Edward Fox-Strangways, 5th Earl of Ilchester PC (13 February 1847 – 6 December 1905), known as Henry Fox-Strangways until 1865, was a British peer and Liberal politician. His mother was a Scottish “Majoribanks” on whom I could find no information.

The Fifth Earl Ilchester’s grandfather, Henry Thomas Fox-Strangways, 2nd Earl of Ilchester (29 July 1747 – 5 September 1802). The Fox-Strangeways were English landowners whose patriarch made their incredible fortune as Military Paymaster under King Charles II. (Merck was Hesse-Darmstadt’s Military Paymaster, but the German state’s resources were smaller. Merck family fortunes came from banking and pharmaceuticals.)

By shifting things up-scale to the anglophile Holland House, “the booking of attractions was emancipated from curb and cafe” as Charles Frohman’s biographer and brother Daniel tell us. (Interestingly enough, the curb and cafe were also stereotypical hang-outs for contemporary pimps!) This “liberation” subordinated an entire industry of criminally-connected players under Frohman’s yoke. Yet, Frohman never seems to have worried that a gang of men like David Belasco’s grandfather would be sent to ‘rough him up’. Instead, Frohman was far more worried about appeasing Philadelphia interests.

The only Frohman Theater Syndicate partners who weren’t part of his ‘London Axis’ were the ones from Philadelphia, i.e. representatives Nixon (born Samuel Frederic Nirdlinger) and John Frederick Zimmerman Sr. (1843–1925). Zimmerman may not even have been Jewish. What we can say for sure is that the Nixon-Zimmerman end of the monopoly got 25% of Syndicate profits, which is extraordinarily high given the number of theaters they controlled. For some reason or other, the Philadelphia end of the monopoly had to appeased. Commentators in Life magazine (“Looking Backward” 1912: 851), when reflecting on how the Syndicate died in 1916, said: "the dissolution of the firm of Nixon and Zimmerman, of Philadelphia, one of the Trust's most important allies, is the latest straw on the breaking back of the camel." (See Greer, 1972.)

In the theater world Philadelphia always had a competitive relationship with New York City. It was a truism that plays which did well in NYC would bomb in the Quaker City. Certainly when British intelligence agent William Wesley Young was padding his theater resume, he felt the need to join the Friars’ Club and the Philadelphia Vagabonds theatrical society. Whatever the reason for this, for David Belasco’s talent to march triumphantly across the new world of entertainment in 1916, Nixon and Zimmerman had to disappear.

Given this reality, it’s worth noting that by supporting his proteges the Schubert Brothers to undermine the Syndicate by buying up performers’ contracts, Belasco was biting the hand that fed him. Incredibly there seemed to be no hard feelings after Sam Schubert was killed in that freak train accident. The Syndicate/Schubert partnership carried on the monopoly until that magic year 1916, when only the British were left standing in Early Film and the East Coast theater scene began its long death.

How strange then, when David Belasco died in 1931, the JTA gave him all the fanfare appropriate for a colleague of Austrian Intelligence Agent Otto Kahn:

David Belasco was held in reverence as the Dean of the American stage and as one of the ornaments of the profession all over the world. On his birthday last year he received tributes from Max Reinhardt, Constantin Stanislavsky, of the Moscow Art Theatre, Daniel Frohman, Florenz Ziegfeld, and other famous men of the theatre.

When his son-in-law, Mr. Morris Gest, roused a storm of protest against his action as a Jew in producing the Freiburg Passion Play, criticism was directed also against Belasco in the belief that he was associated with the enterprise. He issued a statement at the time disclaiming all responsibility for the presentation of the Passion Play. My only connection with the Passion Play, he wrote, was to attend the three final rehearsals. I am no more entitled to praise for the merits it possesses than I am to censure for its production.

Perhaps the take home from all this is that to capitalize on iniquity, you always need another place to run.

Thank you, Adventures in Theater History.