Georg Ferdinand von Springmühl

This post follows on from Otto Kahn and the Origins of the Intelligence Community, in which I promised to bring readers the story of German spy and London publisher, Georg Ferdinand von Springmühl.

Why does this matter to a website about early film in Monroe, WI? William Wesley Young’s NYC “educational film” work— conducted from an office at the Friars’ Club— was done alongside a man named A. A. Brill who was Sigmund Freud’s promoter in New York City and a Hapsburg military careerist. Georg Ferdinand von Springmühl was the publisher of Freud’s London promoter, Havelock Ellis. Springmühl appeared on the London scene in 1882, having published something defamatory against Prince Bismarck and facing imprisonment for fraud in Austria.

Like the18th century Pietist Medikamenten salesmen-publishers before him, Springmühl sold drugs, Merck pharmaceutical products this time, to subsidize his economic/political activities in Britain’s imperial capital.

This is the story of how a psychopath was exploited for 19th century Austrian intelligence purposes.

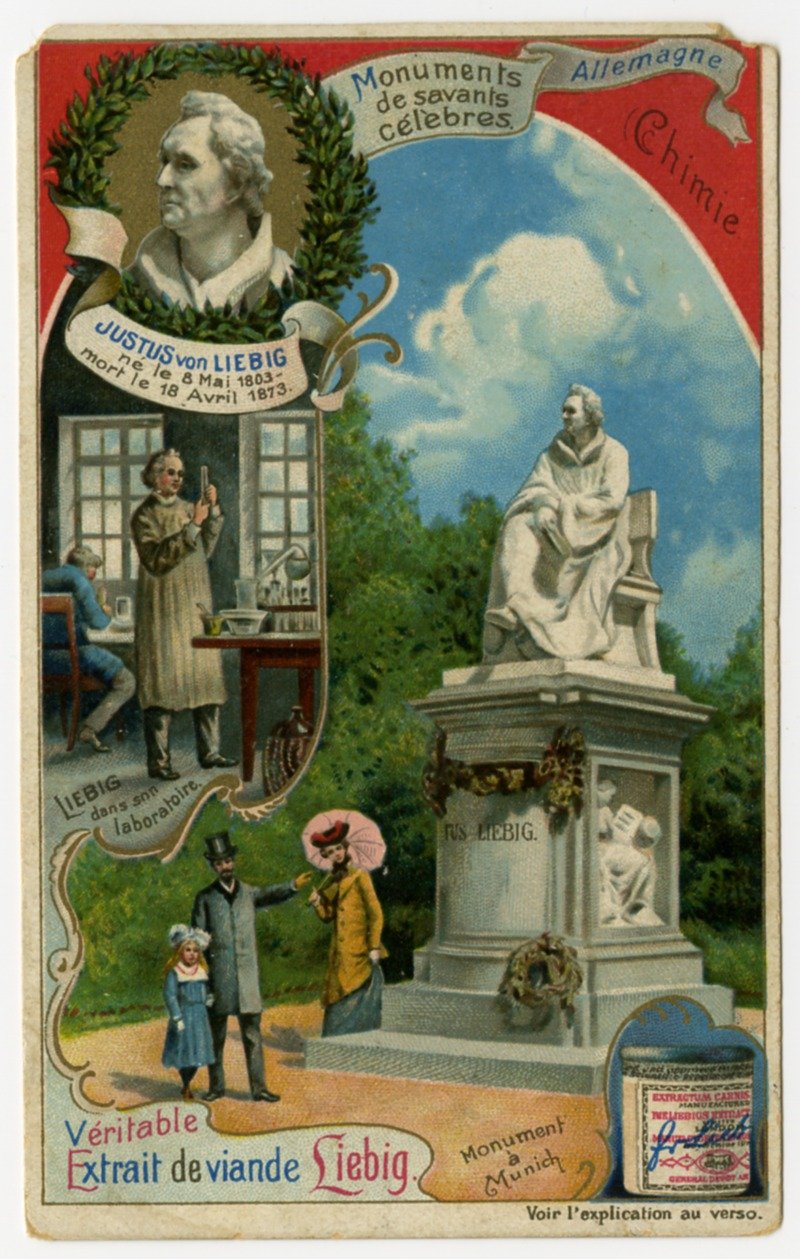

Georg Ferdinand von Springmühl was born in Wetzlar, Hesse in 1851 which was part of Prussia. At this time Justus von Liebig and Emmanuel Merck, an eminent chemist and pharmaceutical magnate respectively, enjoyed a friendship with business benefits. Between them, this duo addressed the problems of feeding large crowds cheaply. Some of Liebig’s answers involved condensing wine or extracting nutrients from meat for cheaper transport, while Merck’s answers involved chemical-sustenance like cocaine. (A drug Sigmund Freud embarrassed himself promoting for Merck & Co. in Vienna decades later.) All of Liebig’s and Merck’s answers would prove formative in young Springmühl’s life.

1903 French trading card for Véritable Extrait de viande Liebig (Real Liebig Meat Extract) depicting Justus von Liebig on the front. There are three main images on the front - central image is of a monument to Liebig, other two images are on the left side - top is a bust of Liebig surrounded by laurel leaves, lower image is of Liebig in his laboratory. Image of product container is in lower right corner.

Georg Ferdinand was an excellent student, taking chemistry courses with the German world’s best professors (at Breslau, Bonn, Berlin and Leipzig specifically). At twenty-two years old he distinguished himself with a doctorate in Chemistry from Leipzig (according to official Austrian sources), but I suspect that his doctorate, if issued, may have actually been from Breslau.

Now this is where things start to get shady. Immediately upon graduating, Springmühl showed that he wasn’t like other chemists: from Breslau, then a Hapsburg city but now Wrocław in Poland, Springmühl became the publisher of Allegemeinen illustrierten Weltausstellungs Zeitung or “Collected Illustrated World's Fair Gazette”. This World’s Fair was held in Vienna in 1873. Springmühl was one of a network of nineteen publisher-distributors, which stretched from New York City to Rangoon. This was a massive, global public relations effort for the Hapsburg Empire in the wake of French defeat by Imperial Germany in 1871, which buried Austria’s hopes of regaining dominance in the German-speaking world. Austria-Hungary still had cards in the game economically, though that would soon change.

Springmühl’s gazette was both a catalog of technology presented at the event as well as a guide to the exhibitions. It had advertisers from German Europe and from New York City, but most ads were Viennese and offered tourist-services. Overall, the publication seems to have been subsidized by the “Austrian Industrial Bank” of Eduard Fuerst.

At very the least, we can say Springmühl’s time studying chemistry at Breslau gave him excellent contacts in Vienna.

Cover image of Springmuhl’s 1873 Worlds Fair publication, which seems to have begun with it’s second series…

The “Austrian Industrial Bank” was a steady front-page advertizer for Springmuhl.

Publisher’s directory of the Illustrated World’s Fair Gazette.

That Springmühl was hired to oversee public perceptions of the Worlds Fair, a high-profile economic event in Vienna, is noteworthy. 1873 was the last year of the Austrian Gründerzeit, a period of intense economic growth and newspaper-driven speculative investment which was fueled by 1) the Hapsburg press-policy of reinforcing institutional corruption at newspapers and 2) the Hapsburg financial-policy of plutocratic favoritism underwritten by state-subsidized banking. The Vienna World’s Fair— planned in the year(s) prior to 1873— would have been something like Gründerzeit fraudsters’ last huzzah.

Naturally, a Worlds Fair publication loses its raison d’etre when the World’s Fair ends. The company which controlled the publication changed hands, and eventually was awarded to a twenty-four year old woman, Gabriele Suchy von Weissenfeld, who Springmühl married in 1875. At around the same time (1875/76) Springmühl took a lobbyist-job on behalf of the Imperial German dye-stuffs industry by editing trade journal Munster Zeitung.

Dark clouds were on the horizon. In 1875 Springmühl first appeared in English-language press: he wrote an internationally-acclaimed book on chemical dyes with particular attention paid to their poisonous properties. This was my first indication of his dark proclivities.

The Chemical News and Journal of Industrial Science, January 15th, 1875 page 29. 1/2

The Chemical News and Journal of Industrial Science, January 15th, 1875 page 29. 2/2

I apologize for the poor resolution of the image above. The reviewer summarizes the different chemical dyes which Springmühl investigated along with Springmühl’s estimations of their poisonous properties, which in fairness should be important to any responsible industrialist.

The year after this book appeared, in 1876, all hell broke loose. Springmühl was charged with libel against Prince Bismarck in Berlin. This is the Austrian wanted-ad for the editor in Neuigkeits Welt Blatt:

“Dr. G. F. (Georg Friedrich) Springmühl is wanted!” Advertisement from the Neuigkeits Welt Blatt, March 15th, 1876, page 8.

Here’s a translation of the pertinent parts of the wanted notice above:

Dr. G. F. Springmhl is wanted!

The Vienna Police Department publishes the following: “Geroge Friedrich Springmühl” from Wetzlar and born in Rhein-Prussia, 25 years old, married, allegedly a doctor of chemistry at the University of Leipzig, is of medium stature, strong physique, with blond hair and dark eyes, particularly recognizable because of one glass eye (on the right). He is dressed in a light-colored coat, gray trousers and German-style hat, [he is wanted] because of complicity in the crimes of fraud and blackmail which are being investigated at the Viennese Regional Court… Dr Springmühl is ***** homeless. He resigned from the Prussian State Association without having previously sought admission to another [association]. A pamphlet that appeared in ******* several weeks ago and contains hostile arguments against Prince Bismarck and Prussia, has Dr. Springmühl as the author.

I did my best to locate what Springmühl actually wrote and all I can offer is this paraphrased description from Der Volkstadt, which was the newspaper of the Social Democrat Party of the German Empire (October 1876):

The ingenious chancellor [i.e. Bismarck] is probably not satisfied with the punishments that are made in "his" empire because of him, he must spread his charges even further, to Belgium, Austria and other "small states" of Europe. In 1866, Dr. Springmühl might have got a medal, but these days he may get a few years [in prison]. Springmühl wrote something strong, he called the action of Prussia after the Franco-Prussian Wars --- --- ---, meaning that the founders of today's amalgamated Germany deserve instead of thanks --- --- --- ---, their egoism was matched by the ethics of a boogeyman, they possessed as little greatness of spirit as a common thief, and that Bismark would not hesitate to --- --- --- the members of the German imperial family if --- ---. [The dashes appear exactly so in the original.]

By “1866” the editor is referring to is the Battle of Königgrätz, during which Prussia decisively crushed Austrian leadership of the German-speaking world. The editor is mocking what he sees as Austria’s consequent subservience to her powerful neighbor.

To my mind, the fraud charges against Springmühl are just as interesting and shed light on the reality of the newspaper biz in post-1848 Europe. (When I know more about the blackmail, I’ll let you know.) According to court reporting from the Morgen Post over October 1876, Springmühl and his wife set up an alternate Leipziger Illustrirte Zeitung in order to steal money from people who thought they were placing ads in the real paper. They did this by re-naming the Weltanstellungs Zeitung— which was now held in Mrs. Springmühl’s name— to Allgemeine illustrirte Zeitung and transferring the printing to Leipzig. They were able to pass their publication off as a paper of greater standing and raise capital on the established newspaper’s name. They engaged an “agent”, Dr. August Theodor Block, to solicit advertising payments in all the chief cities of Austria-Hungary. They bilked quite a fortune from wealthy, educated people in this way. You could say that Springmühl was a consummate con-artist.

Con-artists were of intense interest to the leading psychiatric, criminological and juristic minds of the day in Vienna, Graz and Berlin. This is partly because all universities were state-controlled and the holders of important chairs were contract-bound to appear as expert witnesses in court cases where their knowledge was needed. (Military careerists, like those on the Austrian General Staff, were also bound by the same contracts.)

This charming character is Alfred Redl, wearing what I believe to be his General Staff uniform. As a “counterintelligence expert”, Redl was bound to provide evidence in court against suspected spies, which he did with dramatic flair, if not veracity. Redl was a double agent for Russia, Italy and probably other countries too. Sigmund Freud began his paper On Narcissism in the days following Redl’s exposure, at the height of the media frenzy around this exemplary con-artist.

Redl served as an executive for the military intelligence apparatus, the newly-reinvigorated “Evidenzbureau”, which impinged on the power of the better-funded Foreign Office intel network. When Redl’s treachery was discovered— treachery which undermined the military’s work— the Foreign Office worked hardest to cover-up his crimes.

University expert witnesses were also key to protecting state-sponsored criminal enterprises. When sex-crimes expert Richard von Krafft-Ebing was called to testify during a criminal trial, you could be pretty sure the defendant would be declared insane and basically acquitted. (If they called Julius von Wagner-Jauregg, they wanted the defendant guilty.) There were chemical means to the same end: if it could be shown that the defendant had taken cocaine at the time of the crime, he’d be acquitted by reason of insanity. Cocaine was viewed as a “temporary insanity” drug and a get-out-of-jail free card. E. Merck was the only supplier of cocaine in Europe. [An excellent discussion of this horrific situation is in Magda Whitrow’s biography of Julius von Wagner-Jauregg.] I cannot say when this hypocritical system was devised, but Krafft-Ebing’s career took off in the 1870s.

While wearing their academic hats, these Austrian/Prussian criminal experts identified the same basic psychological characteristics between con-men and prostitutes: a facility for lying and an over-developed, at-will capacity to believe their own lies. They called these psychological characteristics “moral insanity” and you can read more about that here. These experts also believed that this personality disorder could be exploited for ends beneficial to the state. Leading criminologist Paul Naecke wrote in his Über Die Sogenannte "Moral Insanity." (1902):

... individual symptoms may emerge that are not harmful in certain circumstances. [Moral Insanity] Sufferers may still be fairly adaptable, they can make themselves useful when they are guided in the right direction. In former times such guidance was easier than now, and there could even be the aura of heroism around the person concerned.

The criminological/juristic circles which lead Austria-Hungary were often indistinguishable from intelligence community circles, particularly in the case of Hans Gross and Paul Naecke. These same circles were also interested in the psychology of Lustmord, killing for sexual gratification, which modern researchers believe is the motivation of most serial killers. I’ll address Lustmord in a moment.

Unfortunately, I’ve not uncovered the outcome of either of Springmühl’s trials. Given what he did with the rest of his life, readers can rest assured that he was probably guilty of the fraud. However, with so many guns against him, the legal outcome of either case doesn’t really matter. Vindicated or not, Springmühl would have had a reduced circle of people willing to associate with him. Probably all of them in Vienna.

[UPDATE: Springmühl was convicted of libeling Prince Bismarck during a trial in Vienna (he was not extradited) which began on Oct. 7th and ended by Oct 10th. Springmühl was sentenced to three months. The fraud and blackmail charges were not addressed at that time. Neuigkeits Welt Blatt, October 10, 1876 page 4.]

How strange then that when Springmühl next resurfaces in 1882 it is to great fanfare in London. Springmühl marketed himself to London society as a media expert in aconite poisoning following the sensational trial of George Henry Lamson.

Lamson was an American surgeon who volunteered in Romania and Serbia, probably during the Balkan Crisis (1870s). On setting up practice in Britain, he became a morphine addict and dissipated his income. He poisoned his younger brother at boarding school with aconite in hopes of inheriting the majority of their parents’ fortune. Lamson was convicted and hanged.

Turning Lamson’s misfortune into his own benefit, Springmühl courted London’s press with the enthusiasm of Geraldo Rivera. Springmühl gave a talk on aconite to the Balloon Society of Great Britain; he provided an essay for the Pharmaceutical Journal and Transactions (March 25th, 1882); and even an “Original Correspondence” for The Medical Press (March 24th, 1882) wherein he claimed to be a medical doctor.

“Original Correspondence” title in which Springmühl claimed to be an “M.D.”

This “Original Correspondence” is particularly unsettling, because in it Springmühl explains how he first came to be interested in aconite and its poisoning effect:

A friend of mine, an analytical chemist by profession, committed suicide at Breslau in his laboratory, with this poisonous alkaloid [aconite]; he used German aconitine, prepared by E. Merck at Darmstadt, a white powder, which according to all appearances and chemical tests was quite free from impurity, and had been carefully extracted from the plant Aconitum Napellica.

S------, who suffered during the last months of his life from melancholy, took about 5 grains of German aconitine, and I had occasion to observe the whole course of the poisoning, which lead to death after twelve hours of suffering in spite of the application of every possible remedy. Had deceased better known the terrible agonies produced by aconite poisoning which he would have to endure, he would certainly not have chosen this poison. Half an hour after he had taken it, the first violent symptoms appeared, whereupon he exclaimed, triumphantly, “Old boy, in an hour I shall be no more. I took aconitine enough to kill an elephant.”

On the table stood a small bottle of aconitine, out of which not more than 8 grains could have been taken, for the bottle contained no more than 16 grains, and still contained 8 grains of the alkaloid. Unfortunately, S------ had dined before swallowing the poison, which fact caused its action to be considerably retarded and his suffering prolonged. A burning sensation in the throat and mouth first made itself felt, and this became more intense with every minute; intense pains in the stomach began after 30 minutes and these became so violent in a few seconds that the patient writhed, shrieking, in the most dreadful convulsions and trying to strike the walls with his head. With difficulty he was held, and emulsive drinks, as milk and oil, given him. Very soon he became nearly incapable of swallowing and seized with spasmodic coughing and wanting to vomit. In spite of exertion he could not vomit until an hour after taking the poison, and then with violent exertion a dark greenish fluid was vomited, and the patient felt no relief to the pains in the stomach, and the burning in the throat which rendered the swallowing and the application of antidotes very difficult. Neither did the stomach pump (used immediately) give any relief; and although ******* ****** after violent convulsions, the symptoms reappeared with renewed force in spite of all applied remedies. In the commencement of the third hour the pains and convulsions attained such violence that death was expected at every instant, but this did not ensue until many hours afterwards.

In the fourth hour, after repeated injections of morphia, the patient seemed somewhat better. Previous to this he made us understand that his skin was frightfully irritated. This irritation of the skin, as if of ants crawling, continued apparently the whole time, and whenever the intensity of the pains somewhat relaxed, he scratched the skin of his hand and naked breast in a convulsive manner until perfectly sore. His eyes glared wildly about , sometimes resting with a fixed stare at one point. The convulsions were repeated at almost regular intervals, and the inclination to vomit continued, although vomiting did not follow after the second hour. At intervals of about forty minutes the patient seemed to lose consciousness, but only for several minutes, whereupon the convulsions and the other symptoms appeared with undiminished violence. Three hours after the appearance of the first symptoms he became incapable of uttering intelligible words, but made us understand that he felt a giddiness, and a little later he appeared to have lost his sight. He threw himself wildly about on the couch and screamed and groaned so frightfully that I have never heard anything to equal it. Thereupon exhaustion and apparent calm, and then renewed attacks of the most violent descriptions. All attempts to give relief were in vain. Then a difficult breathing set in, and he appeared to suffocate. At intervals he was conscious, and when asked where he felt pain he made rapid motions to his head and stomach alternately and wanted to drink, although he could not swallow. His pulse and temperature fell considerably and before death, thorough exhaustion and unconsciousness set in, cold perspiration covered his whole body, and death-like pallor before this end, which was ****, while all the time asphyxetic death had been expected.

It was harrowing enough for me to transcribe that. For Springmühl, it encouraged him to test the effectiveness of different types and preparations of “aconitine”. He identified different forms of the poison and proceeded to give preparations (dosage guessed!) to himself, other friends and animals. Springmühl prided himself on preparing the most pure forms of “aconitine”. His 1875 book suggests he became interested in other poisons, too. I feel that Springmühl’s reaction to the death of his friend bears the imprint of somebody who wants to relive the experience. The question is, why?

“Sadism”, a medical term, was only just gaining currency in Springmühl’s lifetime thanks to the work of Krafft-Ebing, that psychiatrist in Vienna who specialized in sexual disorders and whom I mentioned previously. Lustmord was also on criminologists’ minds beginning in the 1870s. I remind readers that modern psychiatrists identify sexual gratification through inflicting death or pain as the most common motivation for serial killers.

Austro-Hungarian criminologists and psychiatrists were thinking about these things because they were being confronted with violent, deviant behavior in greater quantity than anyone remembered before. Most historians blame “industrialization” for this, but equally likely was the protection of favored criminal groups who felt free to indulge perversions which their line of business encouraged. A lot— if not most—of mass murderers worked the no-man’s-land between regular society and the demimonde. They targeted people who ‘wouldn’t be missed’ a.k.a. people whose associates had incentives not to report that they were missing or abused.

I’d also like to remind readers that people chose their paraphilias. They may abuse sex as a way of running from emotional pain, but like with any addiction, they need a stronger and stronger dosage for the same “high” next time. In the case of pornography or sex addictions, more and more transgressive acts are required for the “high”. The sex industry is built to cater to this, as it was in the 19th century. Profiting from that “high” was the basic reason that girls were rotated between bordellos regularly; why children, men and transvestites were on offer; and why there were graded payment schedules based on the type of act sold. The sex industry is a cradle for paraphilia and Viennese criminologists understood this very well.

When sex-trafficking networks are protected by the state, one might expect to see a rise in the number and severity of paraphilia like Lustmord which present in society. As these networks metastasize, one might expect to see paraphilia in locations they never appeared before. This is exactly the situation suffered by Hapsburg-ruled societies after 1848; particularly the German-speaking segments after the 1870s.

One might also expect to see more paraphilia among participants in the sex trade, which is exactly the situation described by Charles van Onselen in this work on Jack the Ripper, a Galician Network member, The Fox and the Flies.

You may also be interested in: “Why Los Angeles Became Serial Killer Central in the 1970s and 80s”.

A sensitive reflection on the cultural situation which allowed for protecting the Lustmord criminal is offered by Amber Aragon-Yoshida, in her paper "Lustmord and Loving the Other: A History of Sexual Murder in Modern Germany and Austria (1873-1932)" (2011). I quote below:

The cultural fascination and investment in determining legal responsibility (motivation and sanity) of the criminal (by focusing on his personality, behavior, childhood, head injuries, family history of mental illness, previous crimes, physical body and tattoos, personal biography, medical history, alcohol consumption, and sexual life) rather than the grievousness of the crime or the victims explains the relatively lenient and sympathetic culture of pre-war Vienna toward an intelligent repeat sex offender…

By the end of the nineteenth century, psychiatrists, criminologists, and jurists had become increasingly interested in the link between criminality and individuals with borderline mental abnormalities, that is, those considered neither fully sane nor insane. 6 Professionals focused their attention on these individuals who could function normally in society and yet commit extremely violent sex crimes, rather than on their victims. Psychiatrists and jurists attempted to determine the motivation and legal responsibility of these criminals by evaluating their personality, behavior, previous life experiences, previous head injuries, alcohol consumption, history of mental health, and sexual history. Increased professionalization and medicalization of criminal justice during the late nineteenth century had liberalized the treatment of criminals. Liberal reforms attempted to redirect legal and penal efforts toward the criminal rather than the crime—in order to shift the emphasis from moral retribution to the protection of society and toward individualized preventive measures for criminals. These cultural trends generally improved the legal and social position of criminals (male and female), but they worsened the position of victims of sex crimes before the law, especially urban lower-class women.

While these sex murderers were not dehumanized and regarded as other despite medical views of them as “degenerate,” female survivors of abuse, sadism, and attempted murder experienced much narrower confines in which to express their public voice, turn to the law, and have their own responses paid public attention. Another reason for this change is that when sex crimes became crimes against morality, and thus were no longer crimes against property, sex crimes actually became less serious transgressions against the law in German culture, especially relative to crimes against property in the early 1900s.

Was all this a step forward? Let’s see what happened by the 1920s:

A survey of recent historical studies on the late 1920s and beyond suggests that—in contrast to the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century—legal attitudes toward serial murderers stiffened by the late Weimar period with the string of notorious serial murderers in Germany such as Fritz Haarmann, Karl Denke, and Peter Kürten. These criminals now came to be viewed as monsters by the press. However, with the relaxation of censorship following World War I, artistic representations of sexual murder became more socially accepted. Yet, modern criminology would not begin to pay attention to victims of violent sex crimes in productive ways until decades later…

However, the study of Lustmord within the larger history of criminal justice reshapes the current narrative of German liberalism by showing how only certain kinds of individuals were able to shape the criminal justice system—including repeat sex offenders—while the perspectives of those most affected by violent crimes were inadvertently excluded from the conversation.

As readers may expect, those “artistic representations” sympathetic to sexual predators came from Ringstrasse-promoted artists, whose power didn’t diminish with the passing of the Hapsburgs. Aragon-Yoshida’s examples are Frank Wedekind (an Elf Scharfrichter and Fledermaus Cabaret regular) or Robert Musil (co-traveler with Franz Kafka and Rainer Maria Rilke).

Could it be that Springmühl was just the sort of psychopath who could function normaly on weekdays? A con-artist who could be usefully directed to state ends? I ask readers to form their own opinion based on Springmühl’s activities in Austria’s adversary, Great Britain.

Having built a public image on his aconite obsession, Springmühl proceeded to capitalize on exactly the sort of “feeding large groups of people” problems that Emmanuel Merck and school friend Liebig became interested in twenty years prior. In 1855 in England, Liebig began a business venture with an Australian named James King to export Australian wines around the world. This became unprofitable when the Australian Gold Rush gutted the labor market. By the 1870s, prospects for a global Australian wine market were looking up once again. Liebig had similar business interests in condensed milk products that were not fully realized. (See “Chemical Gatekeeper” by Brock.) Lo and behold, in 1882 Springmühl took out a British patent for both wine and milk condensing technology. He got similar patents from both the Spanish (Port!) and Italian governments, with an eye to their wine export markets.

Patent notices from Engineering [magazine, London], Sept 15, 1882 page 29. 1/2

Patent notices from Engineering [magazine, London], Sept 15, 1882 page 29. 1/2

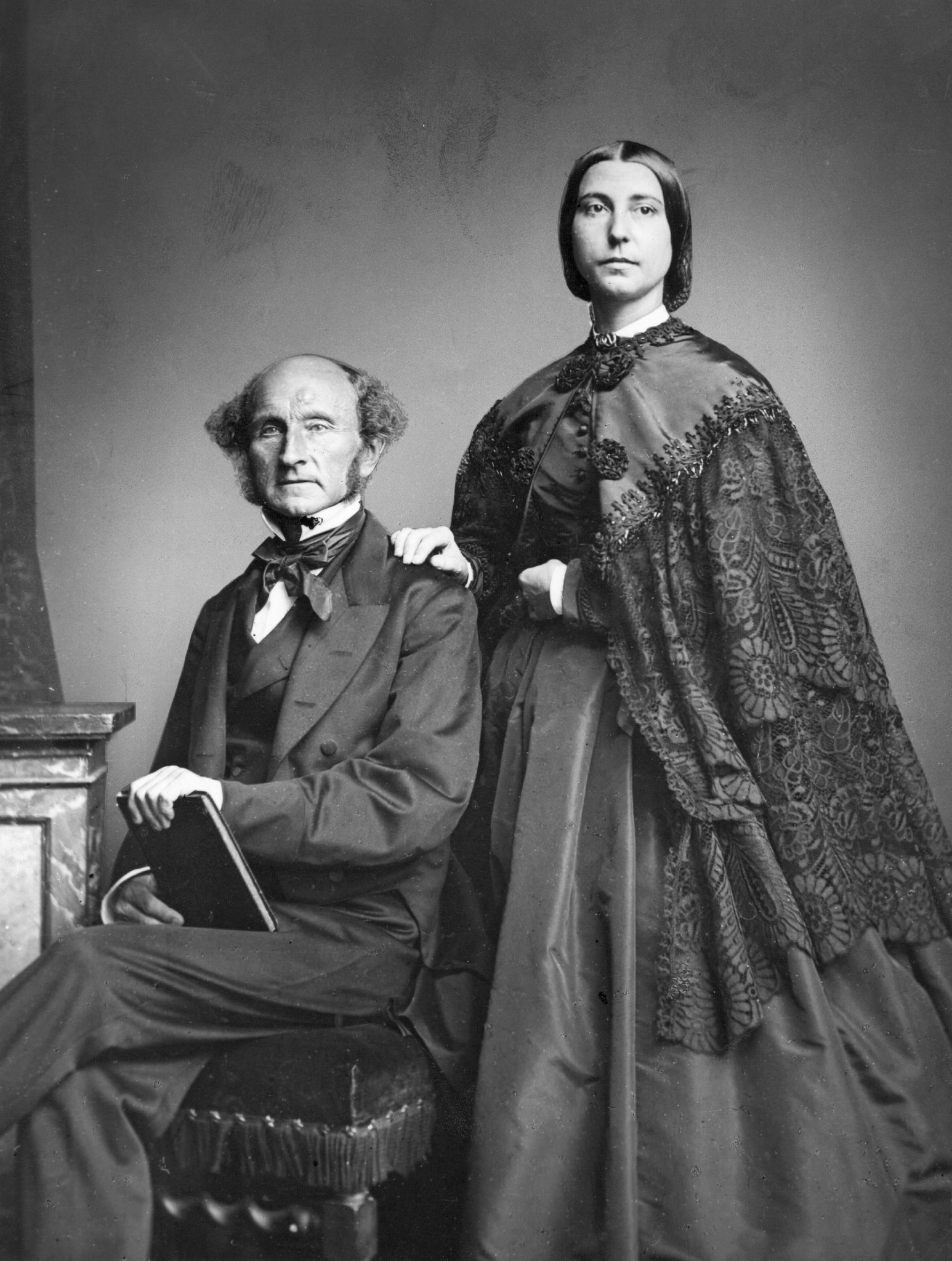

Is it coincidence that Springmühl would revive the old London businesses of Justus von Liebig, businesses that were cut short by the great chemist’s death and adverse economic circumstances twenty years before? Possibly, if organizations with longer memories were not in play. You see, Liebig and Emmanuel Merck were both natives of Darmstadt, one of the leading towns in the complicated Hesse landholdings. Liebig was also a radical politician, as were the preponderance of the Merck pharmaceutical family: he looked to the works of John Stuart Mill to usher forth a sort of utopian liberal world order. In fact, Liebig arranged for the translation into German of Mill’s Logic and its eventual publication. In Vienna the Gomperz Ringstrasse banking family would do the same for other Mill works, employing a then-jailed Sigmund Freud to loosely translate them! (Freud was in jail for eight consecutive AWOLs.)

[I wrote about J. S. Mill before with regard to Cosmo Duff Gordon’s creepy great aunt Lucie, a lifelong friend of the philosopher, who engaged her in his Indian Subcontinent provokasiya as head of the British East India Co.’s intelligence apparatus. Mill was kicked to the curb after the 1857 mutiny and focused on disseminating his writing in the German-speaking world.]

An elderly John Stuart Mill with Helen Taylor, the daughter of Mill’s late wife and sometimes writing partner, Harriet Taylor, in 1858 (Wikimedia Commons):.

J. S. Mill was a radical philosopher and intelligence director for the “new”, unorthodox-investor friendly British East India Co. Besides being buddies with Lucie Duff Gordon, Mill was close family friends of the Viennese-Ringstrasse Gomperz family: insurance and banking magnates who were like hangers-on to the Rothschilds. A family famously afflicted with severe mental illness, their son Benjamin Gomperz tried to kill himself while traveling with the Mills after J. S. Mill forbid him from trying to court his young step-daughter Taylor, who was not interested in the man. The Gomperz family was also close to the Bernays, the family of Sigmund Freud’s wife, who was of higher social standing than the medical student.

In reality, none of this was coincidence. Springmühl was a London drug-agent for the Merck pharmaceutical company, just as his contemporary Sigmund Freud was in Vienna. (And so was criminologist Hans Gross’s son, by the way.) While Springmühl built his grape-must empire, he was also engineering a swindle on the side involving a mythical new medicine: “hopine”. In my estimation, given Springmühl’s relationship with the Merck crew, it’s unlikely his revival of Emmanuel’s friend’s business ventures was coincidence.

The “hopine” swindle was breath-taking in its audacity. It began in 1885, when an article on “hopein” appeared in the German scientific publication Der Forschritt. On August 15 of that year, the New York Medical Journal reported that one “W. Williamson” and F. Springmühl had discovered hopine, supposedly derived from wild American hops, which acted something like “morphia”. This “hopine” was a narcotic, hypnotic, sent the taker to sleep and could cause hallucinations. Supposedly, hopein didn't have the negative affects associated with morphia. At about the same time a London-based drug supplier, W.T. Smith, published about hopine in the Deutsche Med. Zeitung; the Dublin medical press was next to pick up the ‘discovery’. German press stated that the discovery was made during the course of condensing English beer made with wild American hops; English press claimed that the new alkaloid was only found in wild American hops, not in German hops. The ruse continued for over a year and English press was still touting hopine as a new wonder drug to replace morphine and other opioids well into 1886.

By December of 1886, medical professionals began to smell a rat. French chemists investigated hopine and found it chemically identical to morphine. In attempting to test their results, these French researchers (at drug retailer Adrian & Co.) bought hopein samples direct from a London supplier called “The Concentrated Produce Company”. (This firm, “The Concentrated Produce Company”, actually had branches in London and Brooklyn, NY.) When the hopine samples arrived, the receipt was not from “The Concentrated Produce Company”, but rather from Merck (of Darmstadt). This strongly suggests “The Concentrated Produce Company” was nothing but a subsidiary of Merck & Co. It’s also worth noting that Merck & Co. had an exclusive license to distribute hopine in Europe. French researchers came to the conclusion that the product being sold as “hopine” was morphine scented with essential oils.

[I’d like to bring you an example of contemporary Merck & Co. advertising here, but Google is so scrubbed of information on Merck because of the “Corona Virus”, that I’m not able to bring you any!]

One B.H. Paul, an American doctor, put different samples of the ‘hopine’ drug through further testing and found that some of these samples were in fact part cocaine. These cocaine samples were sold through a London supplier; Merck & Co. was the sole manufacturer of cocaine in Europe.

When American tests of American hops were made, no morphine was found in the plant, so Springmühl changed his story: the morphine came from a Central American variety of hops that would be very difficult to locate. The consensus among the knowledgeable was now that a wide-scale fraud had taken place. Sale of hopine was banned in Austria.

Subsequently, the various London merchants who stuck their labels on the bottles of hopine tripped over themselves to point the finger at their suppliers, “The Concentrated Produce Company” (though the drug probably came from Merck originally). In the middle of the furor, a prominent London publication Chemist and Druggist, received a letter from a German “Dr G. V. Weissenfeld” (the maiden name of Springmühl's wife) explaining that nothing was really known about the chemicals in hops, and that hops may very well contain morphine. The letter was vague and didn't stop London druggists' rush to distance themselves from the drug they had sold.

As hopine imploded, Springmühl moved his wine-must operation to California, next stop for every failed London swindler. Springmühl, sometimes working under the name Weissenfeld, set himself up as a “wine expert” with the California Agricultural Experiment Station, got an American patent for his grape must technology, and entered into business with wine magnate James DeBarth Shorb, founding father of the city of Alhambra, CA. This venture didn’t seem to go anywhere. I’d like to point out that all these patents cost a lot in lawyer fees and Springmühl wasn’t great with money.

The next time I can locate Springmühl is in London in 1892, living as von Weissenfeld and facing bankruptcy charges alongside his company “The Concentrated Produce Company”. From Chemist and Druggist, January 18, 1892:

At the same time as Springmühl/Weissenfeld went through bankruptcy court, a previous business partner, manufacturer Edgar Byron Phelps, also sued him for libel and “Weissenfeld” was found guilty. (His deputy at the Concentrated Produce Company got six weeks for perjury during the bankruptcy proceedings.) Things actually get worse from here, readers. In 1895 Springmühl entered the publishing industry. Prepare for more names you’re used to hearing!

Immediately Springmühl’s publising house, named “The University Press”, attracted interesting clients. Frank Hill Perry-Coste recommended to Havelock Ellis that he publish a book on “contrary sexual feeling” , i.e. homosexuality, with Springmühl. (See the Havelock Ellis biography by Grosskurth.) Perry-Coste, who would later change his name to“Perrycoste”, was a step-and-fetch for Francis Galton of University College London which had been founded by J. S. Mill’s dad.

Havelock Ellis, who billed himself as a medical professional though he didn’t finish his studies, was something like a 19th century Hunter S. Thompson and promoter of homosexual lifestyles in a way that the Ringstrasse would appreciate. Ellis was a con-man with a Svengali-like personality; he was also a political radical and who hung around Eleanor Marx and George Bernhard Shaw.

This “contrary sexual feeling” book has an interesting pedigree. In 1892 John Addington Symonds, a Renaissance scholar and advocate on behalf of homosexuality himself, asked Arthur Symons if Havelock Ellis would write a book on homosexuality with him, J. A. Symonds. Arthur Symons was Havelock Ellis's long-time handler as well as a poet and Yellow Book contributor [a.k.a. a member of Sir George Lewis’ stable of writers]. Besides looking after Havelock Ellis, Arthur Symons promoted Oscar Wilde, darling of Vienna’s Ringstrasse. As I mentioned previously, Havelock Ellis was one of Sigmund Freud’s early promoters in Great Britain.

Symonds and Ellis did partner on the book, eventually titled Studies in the Psychology of Sex Vol. 1 Sexual Inversion, but Symonds died in 1893 and Symonds's literary executor, Horatio Brown, had Symonds’ name removed from the authorship on the insistence of the Secretary of State Herbert Asquith. This information comes form Ellis’ biographer Grosskurth, who can only speculate on why the secretary of state would get involved in such a matter: she guesses the reason was that Asquith’s new wife was close friends with the deceased Symonds! Readers may remember that in 1909 H. Asquith would set up MI6’s forerunner in order to combat his political enemies, “tariff reformers,” who were sympathetic to German business interests. Asquith had Symonds’ name struck because he knew full well Springmühl was a German spy. The funding for Studies in the Psychology of Sex Vol. 1 Sexual Inversion came from Springmühl under the name “Singer-de-Villiers”. [Grosskruth, p 193.]

Symonds’/Ellis’ own role in provokatsiya-style espionage is worth mentioning here. In 1894, a female acquaintance of Springmühl’s [possibly a relative, described as an “Austrian aristocrat” in 1907— so almost certainly not an aristocrat] was implicated in an anarchist terrorist ring. She chose to cooperate with the police. It was never proven, but her acquaintance Springmühl was believed to be funding anarchists in London and Vienna under the name “Roland de Villiers”. When organizing their book on homosexuality, the go-between between Springmühl and Ellis, Frank Hill Perry-Coste, recommended to Ellis that he publish the homosexuality book under the name “Dr. Roland de Villiers”, a supposed brother-in-law and agent for wealthy, mysterious “G. Astor Singer”. Perry-Coste and Ellis would joke amongst themselves that “de Villiers” was a shady alter-ego for “G. Astor Singer”. These homosexual activists understood that their “reformer” publisher was not above-board.

As one might expect, the whole operation imploded in scandal, but for reasons you might not expect. Another writer in Springmühl’s ‘stable’ was George Bedborough. Bedborough was the face of the anarchist organization “The Legitimation League” which agitated on behalf of illegitimate children’s claim on their birth-father’s assets, among other anarchist policies. Bedborough also ran a bookstore which sold Studies in the Psychology of Sex Vol. 1 Sexual Inversion; his bookstore occupied the same premises as the business place of one “Singer-de-Villiers”.

Bedborough was arrested in 1898 on obscenity charges for selling Studies in the Psychology of Sex, whereupon Springmühl immediately fled to Cologne and instructed Ellis to “obtain counsel”. Ellis went to live with his handler Arthur Symons and hired a lawyer from the firm that represented Oscar Wilde (opposite Sir George Lewis for a time!), while Bedborough hired lawyer Wyatt Digby. During the trial, Bedborough placed all blame on Springmühl; in consequence Springmühl had Digby “struck off the lists” so that he could no longer practice law.

George Bedborough

During the Bedborough trial, it came out that Ellis never had any confidence in the case histories presented in Studies in the Psychology of Sex, he would not testify to their truthfulness. Most ‘case studies’ had been collected by Symonds, Edward Carpenter and an American medical doctor named J. G. Kiernan of Chicago. [The USA was the wild west of medicine at this time, please see my post on Monroe, WI’s women doctors.] Grosskurth says: “Ellis's book, then, was fundamentally a polemic, a plea for greater tolerance...” She also notes that the book's style was modeled after Krafft-Ebings Psychopathia Sexualis, which he originally wrote with Hans Gross. Dear readers, the genesis of this operation is clear.

By why? Why would Austrian intelligence pay to promote homosexual lifestyles in Great Britain? An answer can be found in Sigmund Freud’s writing. Freud was a kind of weather-vane for fashionable ideas in Vienna’s medical community. His modus operandi was to take fashionable ideas and rebrand them with his own sexual twist. His 1913 conception of narcissism, which he cut short an Italian vacation to make public in the wake of the Redl Scandal, was a frankenstein-conglomeration of “moral insanity” characteristics, like extreme childish egoism, paired with Paul Naecke’s observations of auto-eroticism among institutionalized patients, observations which Naecke christened “narcissistic” having been inspired by the works of Havelock Ellis!

At its core, Freud’s narcissism was a re-branding of “moral insanity”, which well-connected insiders like Naecke recognized could be manipulated in service of the state, if you knew the right way to go about it. According to Freud’s thinking, homosexuality was a prominent expression of this “moral insanity”: that the two would be co-symptomatic didn’t skip a beat. By encouraging homosexuality, particularly among the artistic milieu which German intelligence targeted already, somebody inside Austria thought they were grooming agents. This sort of thinking would resonate strongly with connected Austrian academics, like Theodor Gomperz, who studied homosexual pedophilia in Ancient Greece such as it is expressed in Plato’s Symposium.

The situation around Springmühl also gives us some insight to the foundations of MI6, Herbert Asquith’s weaponization of the state against his political opponents “tariff reformers”. As Grosskurth states, emphasis added:

Before the trial-- by the 11th of October-- Ellis had become thoroughly disenchanted with Beborough and his friends. To Perry-Coste (who was in Cornwall) he wrote: “Seymour, who is an extremely decent fellow, is greatly disgusted with all their crew, and probably will not keep on the Adult. (Don't mention this however.) The less one has to do with “reformers” the better-- with other reformers, of course!”” (Letter from the Lafitte Collection.)

As if things weren’t bad enough for Springmühl, other swindles were catching up with him. By 1900 police believed that Springmühl was earning most of his money by defrauding heiresses, fire insurance fraud [Paddington Pollacky!] and financial schemes. In 1902 police cornered Springmühl, living under the name Dr. Sinclair Roland, inside his palatial estate in Cambridge. There was an actual chase and officers found him hiding in a spider-hole-like secret compartment in his roof. Springmühl asked for a glass of water and dropped dead seconds later. No prizes for guessing how.

Cambridge Daily News, July 25th 1904 page 3.

In 1907, Sweeney published a biographical article on Springmühl. In the article Sweeney claims Springmuhl's wife thought he was “an honest millionaire carrying out a secret political propaganda”. Sweeney believed Springmuhl's theater of operation included London and Vienna. [See Sweeney’s piece in The Strand, September 1907 at the end of this post.]

Havelock Ellis said this of Springmuhl:

“I never regarded him [Springmuhl] a criminal... even now it seems to me that he was essentially a man afflicted by a peculiar mental trait which it would have been psychologically interesting to investigate.” (From My Life, p. 299. First published 1939.)

I think Mrs. Springmühl and Ellis are both half right.