Otto Kahn and the Origins of the 'Intelligence Community'

How does a public figure like Otto Kahn come into being? The Kahn family were well-to-do mattress factory owners, but as bankers they were largely failures and most of Otto’s siblings were dependent on him. How did the family’s aspiring third son become a global power-broker and Austrian intelligence agent? The short answer: Otto’s aunt made a useful marriage.

Otto Kahn’s maternal aunt married a Sephardic Jewish lawyer in London who was at the heart of the burgeoning publicly-funded ‘intelligence community’. That London lawyer was Sir George Lewis, ‘first baronet of Portland Place [street]’. Otto’s fated aunt was named Elizabeth Eberstadt. Marriages in the Eberstadt circle were a political tool and Elizabeth’s alliance with Lewis should be considered under that light.

The Eberstadt family were Jewish industrialists from the same German Duchy that nurtured the Rothschilds, Hesse, and who had battled their way into imperial power by way of the 1848 revolutions. They shared political views with the majority of Vienna’s Ringstrasse patrons: Elizabeth’s father Ferdinand Falk Eberstadt managed the ‘German Progress Party’, the Prussian equivalent of the Ringstrasse’s ‘Constitutional Liberal Party’ in Austria-Hungary.

The Eberstadts reflected the Ringstrasse in other ways, too. Elizabeth’s brother was Otto Kahn’s uncle Edward F. Eberstadt, a financially irresponsible murderer-on-the-lamb who spent his life whoring among NYC’s theatrical talent. Her nephew Ferdinand Eberstadt was a Dillon, Read & Co. executive who helped organize Germany’s post-WWI ‘reparations’ payment scheme (the “Young Plan”), which British historians largely credit for making WWII inevitable.

A study in black and gold: a portrait of Elizabeth Eberstadt by the fashionable society artist John Singer Sargent in 1892. This is exactly the type of portrait popular among Vienna’s Ringstrasse set during the same period. It represents a mutually shared aesthetic creed, to paraphrase Bertha Szeps Zuckerkandl.

There was nothing remarkable about Otto Kahn’s career until he moved to London to live with his auntie. While living with them on Portland Place street, Otto went to work at Deutsche Bank’s satellite office, which was the Imperial German government’s financial concern in London. Kahn’s biographer Theresa Collins says this about Lewis’s influence on his young nephew-in-law:

The Lewis household made Oscar Wilde’s London also Otto Kahn’s London, gay, satiric, and romantic. A costumed epicycle of dramatis personae and artistic wealth opened to him. Kahn chanced upon a crowd for whom art was the secret of life. He found the best light opera, new drama, and literary entrepreneurship, along with beautiful women and the latest gossip. He discovered a passion for Ibsen and Shakespeare, so much in vogue then on the London stage, and he read Thomas Carlyle and Walter Pater, further polishing his sense of heroism, art, and beauty. He loved being around the pacesetters, and as the Lewises knew nearly every future contributor to the Yellow Book, the illustrated quarterly of new artistic literature, Kahn grew acquainted with the poet and novelist Richard Le Gallienne [a sexual partner of Oscar Wilde], whose future daughter, Eva the actress and founder of the Civic Repertory Theatre in New York, would one day benefit from Kahn’s patronage...

The stage, the city, the manor seemed within the reach of a single goal— the English Otto Kahn. He donned a crisp sartorial style, switched his citizenship, and changed his patterns of speech. A German accent lilted through British inflections thereafter, making the origins of his dialect more difficult to detect. In most ways, Kahn adopted the elegance that became Kahn’s armor, for it gave him a means to live conservatively on the edge of scandal. As for secrecy, Kahn could observe its best practitioner: Sir George Lewis. Of the solicitor who so adeptly managed the legitimacy of royal sins, the Crown Prince Edward supposedly said, “He is the one man in England who should write his memoirs, but of course he never can.” Added into the mix was tolerance. When Oscar Wilde prepared Elizabeth Robins for her introduction to Lewis, he offered this cryptic assurance: “Oh, he knows all about us— and forgives us.”

If this all seems a bit “Sidney Reilly” to you, you’re more right than you may know. Sir George Lewis was a lawyer who frequented blatant “active measures” circles in London’s publishing scene, which were paid for by some combination of Prussian and Austrian funding. (A long-standing espionage tradition by this time.) Lewis’s connection with the story of German-spy-cum-publisher Georg Ferdinand Springmuehl, a psychopath with a penchant for aconite-poisoning, is one I’ll be bringing to you in time.

For now, readers may like to reflect on how Sir George Lewis nurtured a stable of writers (around the Yellow Book) and entertainment/artistic talent just like Otto Kahn did. In fact, the earliest example I’ve found of such nurturing was that of Johann Heinrich Merck, the “DNI” of Hesse-Darmstadt. (His family now brings you vaccines.) Thomas Carlyle was a devotee of J. H. Merck, and Walter Pater wrote on Renaissance/Platonism/Male Love topics near to the heart of the Ringstrasse and their satellite Sigmund Freud. (Springmuehl was a drug agent in London for Merck’s family, and the publisher of Freud’s Anglophone cheerleader Havelock Ellis.)

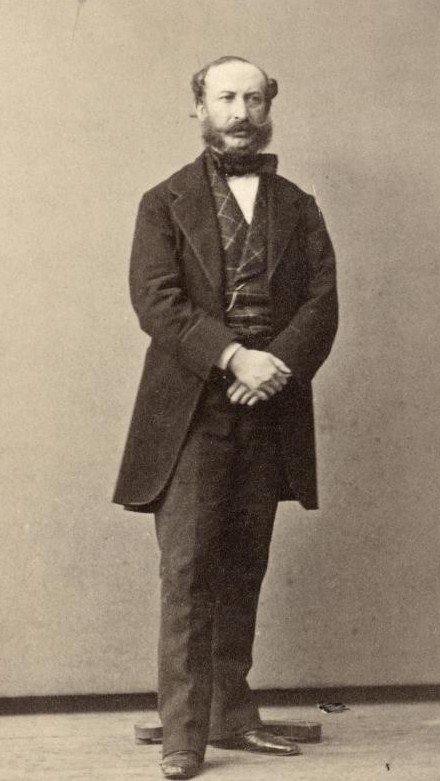

A fashionable portrait of Sir George Henry Lewis by John Singer Sargent in 1896.

So who was this remarkable figure Sir George Henry Lewis? His family history is a window into the political climate in Great Britain at the end of the 18th century, the time when German-speaking financial interests in London were consolidating their control over the great monopolies which made up the “British Empire”. (See “The Forgotten Majority” by Margrit Schulte Beerbühl.) Wealthy Jews had first reestablished themselves in London during the reign of Queen Anne (1702-14), the last Stuart. These Jews sought expensive “naturalization” privileges from the Home Office which allowed them to conduct open, legal international trade.

With the arrival of the Hanoverians British immigration policy changed dramatically. By the end of the 1700s a large number of poorer Jewish subjects from the Holy Roman Empire, the European Sephardic diaspora, and even returns from the New World had establish themselves in British metropolitan centers. “Naturalization” was beyond their economic scope, so smuggling (particularly via the Netherlands) was their ‘thing’. George Henry Lewis’ first identifiable ancestor, Moses Levi, would most likely have been part of this poorer set of immigrants, though I’ve found little information on him.

We don’t know where Moses Levi was born, but we know that he died in 1798 in Canterbury, the throne of the like-named archbishop who is the Church of England’s equivalent to the pope. It’s an interesting place for a Sephardic Jew to pass away. Moses Levi’s wife Phoebe died in 1808 in the London suburb of Highgate, a far more likely point of departure, which was popular with German-speaking people in Jewish social spheres for a long while thereafter. (Karl Marx is buried there and Highgate was even home to the Hitler family for some time.)

Highgate was considered a lovely, village-like London neighborhood and attracted people with some money, aka “bohemian intelligentsia”. The image is of Holly Village, a property developed by a heiress of the Windsors’ banker Coutts. Thanks, londonxlondon.

Moses Levi’s son took the name “Noah Edward Lewis” and worked on a ship. Noah’s boys, James Graham and George, got into the criminal defense lawyer business at a time many of their coreligionists found themselves on the wrong side of the law. According to Todd Endelman in The Jews of Georgian England 1714-1830:

One major consequence of the lower-class orientation of so many English Jews was that a very visible portion of that community engaged in criminal activity, either on an occasional basis or as a full-time occupation.

The first place this “visible portion” ended up when caught was “The Old Bailey”, the central criminal court of England and Wales in the heart of London. Typically their crimes involved organized commercial sex (including White Slave Trading and child grooming) or theft. Prominent sideline industries were prize-fighting, pawn-brokerages (fencing stolen goods), counterfeiting and insurance scamming. Most of this criminality centered around theater districts, wherein actresses would double as prostitutes. Dickens’ Oliver Twist (first serialized in the late 1830s) was influential because it spoke to the spirit of the times. There were plenty of poor men (and madames!) in the Jewish community who needed a good lawyer.

Lewis & Lewis thrived in this environment:

Excerpt from The Bar and the Old Bailey, 1750-1850 By Allyson N. May · 2015

What Allison May leaves out from the above was that Lewis & Lewis also specialized in representing theater people and literary personalities: ‘influencers’ as we would now term them. The sphere of the theater and the prize-fighting ring combine in London in a way which shows us how ‘Galician Network’ pimps were becoming the first “Pinkertons”, or organized thugs-for-hire, under the patronage of sympathetic friends in law enforcement. (At this time, Jewish organized international prostitution networks were centered around Hungary, Galicia would take over after the 1870s.) Historian Todd Endelman describes this ‘Pinkertonesque’ combination (The Jews of Georgian England 1714-1830):

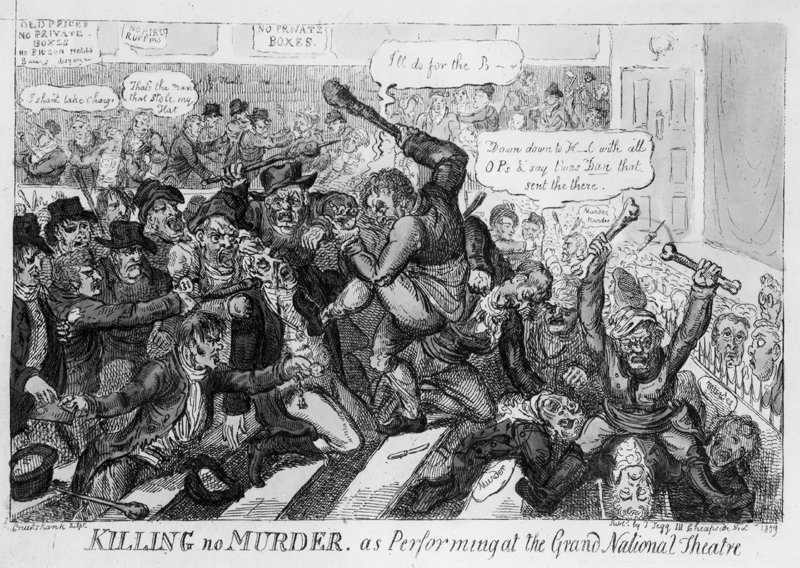

One event in particular managed to fix the image of Jewish boxers as audacious ruffians and bullies— this was their participation in the Old Price Riots of 1809. The Theatre Royal in Covent Garden, having burned down the previous year, reopened in a new building on 18 September 1809 with a rise in the price of tickets and a reduction in the number of inexpensive seats. At every performance during the first week of reopening, the audiences protested the rise with catcalls, hisses, rattles, whistles and trumpets, so that it was impossible to hear a syllable uttered.

Toward the end of the first week in October, the clamor not having died down, the management hired a number of Jewish pugilists and rowdies, including Daniel Mendoza and Dutch Sam, to keep order inside the theater. They also gave Mendoza and Dutch Sam a large number of free passes to distribute to their friends in order to lace the audience with pro-management forces. Persons who hissed or shouted were challenged to a fight or roughed up. [Pages 221-222]

The management of the Covent Garden theater (who appear to have been Jewish at this time) were at the head of a trend throughout 19th century Europe: Jewish factory owners in Poland and Russia hired the Galician Newtork pimps to “rough up” striking workers; militaries everywhere were learning to use the Galician Network for military information; domestic police and foreign offices did the same for political and economic information. The Galician Network were global “Pinkertons” before the famous detective agency was a glimmer in Allan Pinkerton’s eye. The Galician Network was so well placed because of synergies between their breadbasket, White Slaving, and 1) international (socialist) anarchism and 2) counterfeiting: all of which drew heavily on Jewish manpower.

Cartoonist Isaac Robert Cruickshank’s portrayal of the “Old Price Riots”. The beards, hats and shabby clothes betray the aggressors as contemporary Jews of the prize-fighting stripe. The comments in the background: “I don’t take change.” (anti-counterfeiting) and “Who stole my hat?” (anti-theft) reflect the nature of the criminal activities the theater became know for under the contemporary management. The ethnically English audience was preyed upon in a multitude of ways.

Jewish society in Western Europe was highly stratified. In cities like London or Trieste, where rich Jewish merchants found imperial favor, there usually developed a small clique of elite families who acted as shtadlanut or “intercessors” between the Jewish community and local authorities. Underneath this favored class was a large, transient mass of poorer people, many of whom were sustained by charity— either Jewish charity or at the native taxpayers’ expense (usually both)— and who were engaged in organized crime. The shtadlanut class benefited from whatever organized crime went on and it was in their interests to keep both local authorities content and profitable Jewish businesses running. As principal attorneys to the Old Bailey the Lewis boys were in a prime shtadlanut position.

How does this work in practice? Here’s a fascinating example from the case of “Madame Rachel Levison”, a whore-house and assignation-house operator on New Bond Street who ran a Jeffery-Epstein like kompromat factory from her premises. Sir George Lewis represented the government in her eventual prosecution. This prosecution only happened once a victim of Madame Rachel with nothing to lose came forward to press charges. Prior to this remarkable event, Sir George Lewis would advise clients not to press charges, but to pay Madame Rachel off because of the damage Madame Rachel would otherwise do to the victims’ reputations. Sir Lewis was Madame Rachel’s last and best line of defense. In the words of Madame Rachel’s biographer Helen Rappaport, “Lewis knew that to reveal the true extent of the goings on at New Bond Street would rock the very foundations of Victorian society.” [See Beautiful for Ever, page 97.] Foundations which were built on new wealth, I might add.

Madame Rachel Russell/Levison/Levi. Rachel, a former prostitute who preyed on prostitutes in her old age, had an informal marriage with a deadbeat husband surnamed Levinson, which was a very common situation among the Galician Network and the sex trade more generally.

All sorts of creepiness went on at Madam Rachel’s New Bond Street ‘Arabian bath’, including voyeuristic services. Rachel was rarely out of court, either as a defendant or plaintiff. She was an expert at manipulating bankruptcy law and regularly exploited her children in this regard. Her public “cover” was as a high-priced cosmetics expert, mostly for actress-prostitutes and wealthy middle class women.

There is no reason to believe Lewis & Lewis limited themselves to offering this type of ‘advice’ just to Madame-Rachel-associated clients, either. Writing about the firm in 1927, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency noted:

Few of their cases were ever brought to eourt [court]. Most of their ellents [clients] relied on their ability to make settlements and it was said that three fourths of their bnsiness [business] was of this nature.

The vast majority of Madame Rachel’s clients and marks were from the socially aspirant upper middle classes: merchants, wealthy theater people, elected politicians and the like. Ringstrasse-like people. Very few aristocrats are actually named in Rappaport’s biography, clients of Madame Rachel or not, but one who is is important: Crown Prince Edward. Much like Crown Prince Rudolf in Austria-Hungary, Edward was instrumental helping the shtadlanut class enter the corridors of British society and power, Collins:

A prosperous segment of wealthy Jewry, especially financiers from the City, gradually found opportunities for political office, ennoblement, and intermarriage with Gentiles in England. They also had a niche in smart society, due mainly to the disposition of Edward, Prince of Wales, who counted a good number of prominent Jews within his entourage. Among them was George Henry Lewis (1833-1911), the high-society solicitor who had married Kahn’s aunt Betty Eberstadt. [Page 44]

Goetz historians will remember that Ziegfeld costumer Lady Duff Gordon relied on the new wealth enabled by Crown Prince Edward to build her reputation and lingerie business, as did her smut-peddling business partner and sister, Elinor Glyn, benefactress of a Ringstrasse “Grunderzeit” banking fortune. Both LDG and Glyn became promoters of the Early Film business, naturally.

By granting favors to all the right people, Sir George Lewis made himself a repository of very valuable information. Rappaport goes on to explain:

In his professional capacity George Lewis had already more than once come across Sarah Rachel Levison, aka Madame Rachel, thanks to his own appearances in court and his ‘spider’s web of narks’, who fed him all the gossip. During his long career Lewis became privy to many scandalous secrets in Victorian society; indeed it was said that he ‘held the honor of half the British peerage in his keeping’. Rumours had long since filtered through to him, from his uncle’s theatrical clients and his own spies, about the darker side of Madame Rachel’s business in New Bond Street, the allegations of blackmail and the services that were rumored to be on offer there.

And the clincher:

There remains one final tantalizing puzzle: what happened to those account books and the details of Madame Rachel’s many and celebrated clients? The key to the truth about her dubious business concerns and criminal activities, from her earliest days in Drury Lane till her 1878 trial, almost certainly went to the grave with Sir George Lewis, knighted in 1902 and for fifty years London’s leading criminal lawyer. Whilst Leontine/Alma [Madame Rachel’s exploited daughter] may, in the end, have had pressure brought upon her not to publish or had even been bought off, the ultimate scandalous memoirs of the century would undoubtedly have been those of the highly-connected Lewis. But he gave up keeping a diary in the 1870s, when representing clients in some very high profile court cases including the Tranby Croft gambling scandal involving the Prince of Wales [Crown Prince Edward]. Interviewed in 1893, he remarked in typically sphinxlike manner that ‘No novel was ever written, no play ever produced, that has or could contain such incidents and situations as at the present moment are securely locked up in the archives of memory which no man will ever discover.’ He later destroyed all his professional papers, long held in the strong room at 10 Ely Place [the offices of Lewis & Lewis, 10-11 Ely Place, Holburn Circus], swearing that when he died ‘all the confidences of London society’ would die with him.

So Madame Rachel’s records went the same way as the “'Young [Name] + [Name]” Ghislaine Maxwell/Jeffery Epstein tapes. Some things in “intelligence” never change.

But really, Madame Rachel is a side-show in the Sir George Lewis story. The real character I want to share with you today is one of Lewis’ clients: Ignatz Paul “Paddington” Pollaky, the Austro-Hungarian “real Sherlock Holmes”. Pollaky is perhaps better described as Sir Lewis’s “nark-in-chief”. Much of the information which follows comes form Bryan Kesselman’s ‘Paddington’ Pollaky, Private Detetive: The Mysterious Life and Times of the Real Sherlock Holmes.

The cover of Kesselman’s book, a well-researched work which would be excellent if Kesselman’s analysis placed his sources in historical context. The cover image is an 1874 caricature of Pollaky by Faustin Betbeder.

Cut to the chase: Pollaky was was a Galician Network insider who was helpful to Sir Lewis through working with the Lloyds Salvage Association (LSA)— the intelligence branch of the insurance marketplace ‘Lloyd’s of London’. Pollaky did more than one investigation for Lloyds, and was instrumental ferreting out a particularly hairy piece of insurance fraud which threatened to cost Lloyd’s GBP 14,600 in 1860.

This is far more significant than it first appears because prior to the establishment of professional state-sponsored intelligence gathering agencies, national governments depended on commercial networks for foreign intelligence. In the case of Britain, the government was particularly dependent on Lloyd’s and its insurance fraud investigative teams, including the LSA, which in turn appears to have been dependent on Pollaky, especially when the ships’ crews were German-speaking. [A fascinating book on this thorny subject is the 1876 book “A History of Lloyds” by Frederick Martin.] Ships being criminally scuttled and then insurance policies being cashed on them and their cargo was a huge, recurring problem for Lloyds. Certain waterways on the return voyage from India were fraud hot-spots. (Suggesting the Indian exports were systematically overvalued?)

Most of the British Empire’s foreign intelligence was collected between Lloyds, the Royal Navy and the British East India Co, which were in practice three parts to the same state-subsidized business concern. By the 1800s the BEI Co and Lloyds were controlled by families of German-speaking merchant bankers who resided in London, but were originally from Holy Roman Empire territories. (See Shulte Beerbuehl.)

John Julius Angerstein built Lloyds into the Imperial Goliath that became the envy of both the Hapsburgs and Hohenzollerns. Angerstein was born into a German-speaking merchant family which had settled in St. Petersburg, but he built his fortune in London’s insurance markets. The slaving port of Trieste is famously home to the Hapsburg’s corrupt knock-off company; while Bremen’s Norddeutscher Lloyd was far more serious competition and a driving force for British participation in WWI.

We know that White Slavers from Czernowitz in Austria-Hungary played a role in intelligence gathering in the British Empire, particularly in India, where the supply of European prostitutes for British servicemen was a political and public health flash-point. These slavers, called “Bombien” in German as many docked at the port of Bombay, were an unusually wealthy, “inbred” according to Edward Bristow, violent and well-connected subgroup of slavers who controlled the second most important embarkation point for slaves being trafficked out of Austria-Hungary. [See Bristow, Prostitution and Prejudice.]

We also know that Paddington Pollaky referenced the circa-1857 help he’d offered to the British Government regarding British East India Co. business when trying to get his coveted “Naturalization” from the Home Office in 1862. Lord Palmerston, a personal correspondent of Pollaky’s at this time, moved BEI Co control to the British Government in 1858, following the 1857 Indian Mutiny, which I wrote about with respect to LDG’s creepy in-law Lucie Duff Gordon. (Lucie’s childhood surrogate brother and the BEI Co’s head of intelligence, John Stuart Mill, fell from political grace at this time and hired a young jail-bird named Sigmund Freud to translate his philosophical essays. Freud had limited English and no previous translation experience; he was in jail for repeated AWOLs.) Pollaky’s initial naturalization request was denied because police and Home Office officials regarded him a “man of very indifferent character”. Here’s the desperate letter Pollaky sent trying to get the refusal overturned:

An image from the British National Archives Home Office Collection: H.O. H5/O.S. 7263. This is an 1862 letter sent by Pollaky as part of his disrespectful correspondence with the Home Office regarding his refused naturalization request.

In the above letter, Pollaky references several favors he’d done Lord Palmerston, aka Henry John Temple, a supporter of both the 1848 revolutions in Europe and Christian Zionism. Lord Palmerston tended to do the will of Lord Rothschild, head of the British branch of the Rothschild family and also a dedicated Zionist**:

$3rd That Lord Palmerston has employed me in Secret Mission and that I for such services received GBP 400 to 500, (*) of which a Record will be found.

$4th That Mr. Hodgson Chief of the detective City Police wrote a letter to the Austrian Ambassador in London and which letter is still on Record in the books of the City Police, stating that during my residence in London my conduct was very good and that I was at many occasion, instrumental in bringing Foreigners to Justice--

I trust that You will be good enough to lay this facts before Sir George Grey who will upon referring to the Police for the strict investigation of this facts find that I am not unworthy of the Grant I so earnestly solicit and to which my good conduct entitles me.

[Sideways in the margin]

(*) I may also state that I can produce a certificate from the Austrian Government certifying that there are only technical objections to my return to Austria .

I can produce evidence of what I state in $3rd and Ross D. Mangles Chairman of the East India Company paid the money by direction of Lord Palmerston

The Imperial Austrian ambassador in London at the time of Pollaky’s writing was Rudolf Apponyi de Nagy-Appony, of the noble Hungarian family who, since their political prominence, were seated at Pressburg, Pollaky’s hometown. The Apponyi were a long-standing diplomatic family in what became Austria-Hungary over Rudolf’s working lifetime. Like Pollaky, they were sympathetic with the aims of the 1848 revolutions and established good relations with the Roosevelt family in the USA.

In a weird political twist which is partially attributable to the politics of Empress Sisi and partially attributable to the economic clout of the Ringstrasse Patrons, Hungarian revolutionaries gained an incredible amount of power inside Imperial Austria’s/Austria-Hungary’s foreign service and therefore the empire’s intelligence and newspaper apparatus. The Apponyi benefited from these politics, and apparently so did Paddington Pollaky.

In addition to his British East India Co. work for Lord Palmerston, Pollaky also provided the future prime minister with intelligence on Bucharest (from around the time Wallachia and Moldavia were united to form Romania) and on Egypt, where events surrounding the building of the Suez Canal were heating up and London sought to stave French interests through a temporary alliance with Vienna and other Central European powers. (LDG’s creepy great aunt-in-law seems to have been a British informant in Egypt too.)

Besides Lord Palmerston, Pollaky served as a spy for Lord Lytton from 1858. Lord Lytton was a literary figure who became Secretary of State for the Colonies. Pollaky informed on events around the Ionian Isles and particularly “Syra” Syros, an important trade and naval city after the 1821 Greek Revolution, when ‘interloping traders’ in London were trying to undo the ancient, aristocratic trading privileges native Brits enjoyed with the Ottomans. German-supported Anglophone publishers in London, including that of Lord Byron, were politically active in this partisan economic cause.

Lord Byron in 1813 by Phillips: Lord Byron was active promoting the cause of Greek independence from the Ottomans, which was contrary to official British Foreign Office policy, but benefited investors of immigrant descent in London, who envied native Brits’ trading privileges. Lord Byron’s publishers destroyed his memoirs after he was killed fighting. Byron was a tragic, confused figure with an addictive personality.

Stateside, Pollaky was no less active. During the US Civil War (1860-65) Lincoln’s government hired Pollaky to spy on Confederate agents in Europe and frustrate Confederate attempts to buy ships built in Great Britain. Such was Pollaky’s reach that his American paymaster, Henry Shelton Sanford (1823-91) first made contact with him as US Minister to Belgium. The US Consul in London directed Sanford to Pollaky with the proviso: “there may be some risk in dealing with him, but it is a “risky business” anyway & I think we better engage him at once.” [Kesselman]

Not every American military specialist or diplomat was enthusiastic about hiring someone like Pollaky, and US Ambassador Francis Adams employed a rival set of Dublin-based detectives from the firm of Matthew Maguire towards the same ends. There was some sense to this, as Pollaky very often misspelled or confused the names of his various American marks: the kiss of death for any serious intelligence gathering professional. Yet, there seemed to be a core group of passionate diplomats who insisted Lincoln could not get on without Hungarian Jewish friends. Much of Pollaky’s time was spent tracking (bribing postmen for) information on Capt. James Dunwoody Bulloch, a purchasing agent for the Confederate Navy, whose half-sister would give birth to Theodore Roosevelt.

How did Pollaky see himself in relation to the Americans? He had a habit of signing his reports with cheeky references to the great spymasters of the past. For instance, one letter he signs “Vidoqc I”, which Kesselman interprets as a nod to the earlier criminal-turned-informant Eugene Francois Vidocq. [Kesselman p 62 referencing a ~9 October, 1862 letter in HSS.139.13.3]. More often, Pollaky signed off as “Mephisto” which is a reference to Hesse-Darmstadt intelligence head Johann Heinrich Merck, who was famously the inspiration for “Mephistopheles” in his protege Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s play Faust. While this might seem obscure to Anglophone readers, for someone in German-sphere intel in the 1800s, such a signature would seem painfully big-headed, one might even say narcissistic.

Photograph of a well-to-do, elderly Ignaz Pollaky. Image from Kesselman’s book, original held in the Leo Baeck Institute in NYC.

The above paragraphs explain the highlights of Pollaky’s career, but the vast majority of his cases were not involved with international intrigue. Pollaky’s bread-and-butter was finding out information on 1) cheating spouses and 2) women and children trafficked for the ‘Galician Network’, i.e. Jewish international organized prostitution networks which were at this time based out of Pollaky’s homeland Hungary. Pollaky became the go-to investigator for the London Society for the Protection of Young Females, and was so much connected with this anti-trafficking organization that the press sometimes mistook him for the society’s secretary, J. B. Talbot.

The clannish nature of these organized slaving networks was such that nobody on the outside could have the type of information that Pollaky was privy to. The fact of the matter is that Pollaky provided trafficking information over an extended period of time and was well enough versed in the tactics of slavers to monitor the trafficking of dozens of women and abducted children. One might congratulate Pollaky on dangerous humanitarian work, but one should also bear in mind that to maintain these connections and his public profile, Pollaky would have had to come to some sort of deal with the traffickers. The more likely reality is that a few dozen women and children were saved— for payment— so that thousands upon thousands could be trafficked unhindered. This was an extremely lucrative crime which attracted the business partners of firms like Kuhn Loeb & Co.

As one might imagine, the type of business Pollaky engaged in was prone to bring him into legal trouble himself. Fortunately, he had the excellent counsel of Sir George H. Lewis. Unfortunately, living above the law also means living outside it, and the criminal underworld would eventually catch up with the shtadlanut don on August 9, 1927. Jewish Telegraphic Agency:

Sir George Lewis, prominent Anglo-Jewish barrister, was killed yesterday at Mont-reux, Switzerland, when he fell from the steps of the Grand Hotel, under a railway train.

Interestingly, this exact same mode of death befell Emmanuel Freud, one of Sigmund Freud’s Manchester uncles, on on October 17, 1914. Freud historian Peter Swales believes these Manchester Freuds, originally from Galicia, to have been involved in sex trade trafficking through Greece. [See Arc de Cercle 1.1 (January 2003)] Sex trafficking may be the answer to the long-asked question of how Sigmund’s sexually abusive father supported his large family.

That’s how an Otto Kahn comes to be. So how does this relate to the modern “intelligence community” in the Anglophone world? Well, Noah Charney gives a summary in his article “Lincoln's spy: How Pinkerton laid the foundation for the CIA and FBI” (Salon.com, November 12, 2017):

In Europe, Eugene-Francois Vidocq may be considered the godfather of the former criminal turned secret agent who is largely responsible for the development of the modern, entwined arts of intelligence-gathering and criminal investigation. But stateside, his parallel, no less influential, was Lincoln’s spy master during the Civil War, Allan Pinkerton…

…In his [Allan Pinkerton’s] final years, in direct parallel to Vidocq, he was at work on a way to organize and centralize all identification records on criminals. Pinkerton’s two institutional legacies, the Detective Agency and the Union Intelligence Service, are considered the direct predecessors of the FBI and the CIA. The way American governmental organizations investigate, whether nationalized crimes against citizens or foreign threats, hearkens back to one man.

To a large extent, networks of criminals-turned-informants were ‘made legit’ as federal-level law enforcement agencies from the 1860s onward. We saw this before with respect to the Goetz story and the “Bonelatta” counterfeiting crew who occupied Monroe, WI between 1857-1871. The US Treasury’s “Secret Service” was originally outfitted with crooks who ‘policed’ rival gangs. The extent to which the cultures of these organizations have changed has only been too obvious in US political culture since 2016.

** Zionism played an important and mercurial role in the USA’s entry into WWI. Please see my post Imperial German ‘Active Measures’ and the Founding of the NSA.