Alfred Cheney Johnston: Lies About His Past

I have an interest in financial history. When I read that Alfred Cheney Johnston was the “son of a New England banking family”, my first impulse was to find out which family. As it turns out, I’ve been repeating a lie. The real Alfred Cheney Johnston was a man of more humble roots, whose publicists probably wished to cash in on the cachet of the “Napoleon III” Johnstons, or the “Washington Square” Johnstons, or some confused aspirant conglomeration of both.

So there will be two parts to this post: the exposé of Johnston’s real family history and some backstory to the eponymous Napoleon III/Washington Square clans. I think part two is necessary because it sheds light on the psychology of the people A.C. et alia wanted to bilk: NYC’s class of robber barons pretending to be the new “Nobs” as well as their hangers-on, who were legion.

Please Stand Up

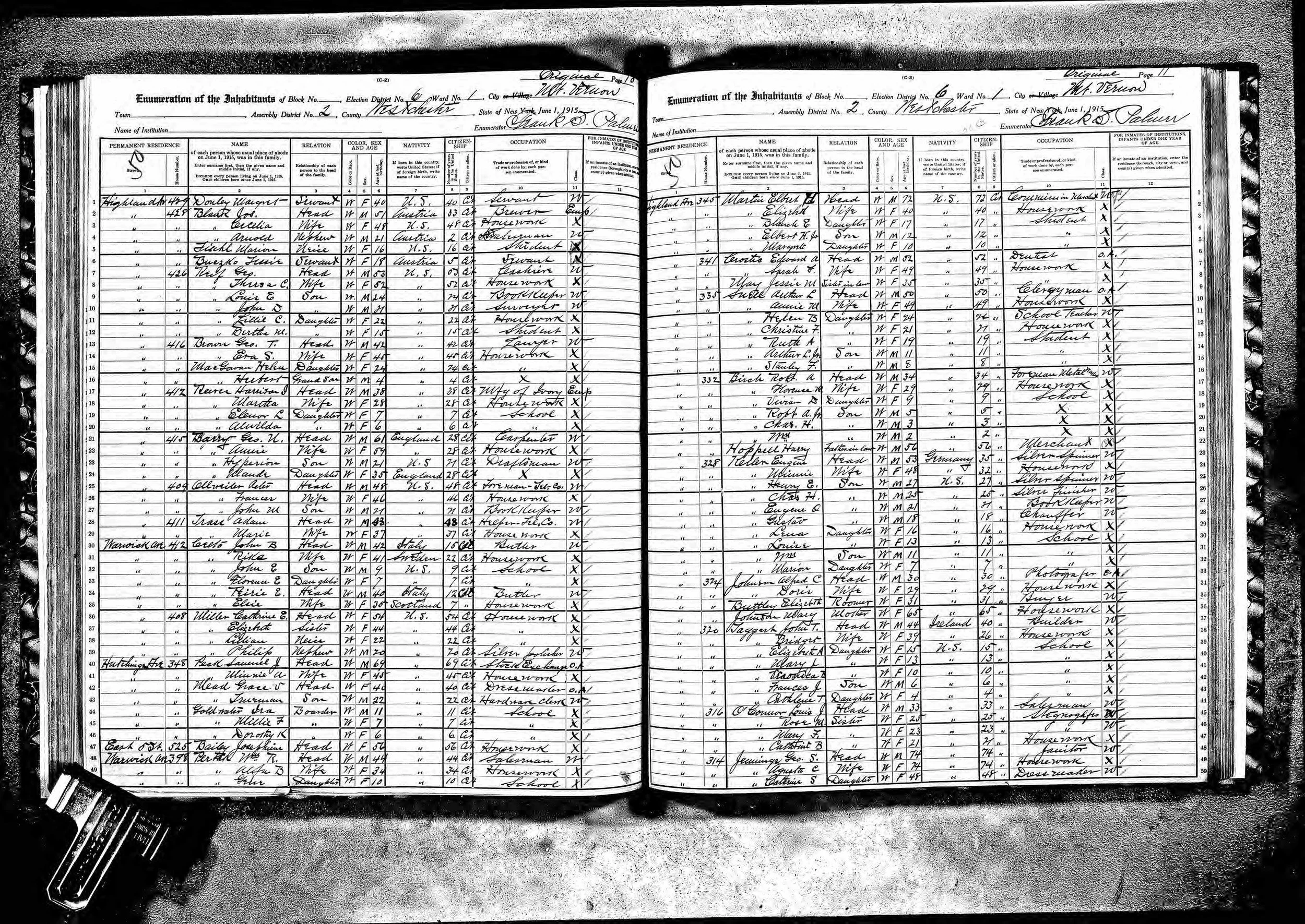

Alfred Cheney Johnson was born on April 8th, 1885 in Westchester County, New York state. Here’s the 1900 US federal census which caught Johnston at 15 years old. (The 1890 national census records were destroyed by fire in 1921, so the 1900 sampling is the oldest record of Johnston we’ll get.)

Image from the 1900 US Census. Accessed through Ancestry.com.

Here’s a close-up of the relevant entry (try zooming in via your browser or download the picture). As you can see, A.C.’s dad was an Irish immigrant (he came over in 1846) who worked as a “bank clerk”. A.C.’s mother, Mary, was almost twenty years’ her husband’s junior. If the Johnstons were from a wealthy New England banking family, it was the type who rented their home and took in “boarders” (sixteen year old Lizzie Buttley). The family lived in Mount Vernon City, in the rurals above the island of Manhattan, on what I believe is “North 8th Ave”, i.e. between West Lincoln Ave and Valentine Street.

Close up from the image above, 1900 US Federal Census.

Mount Vernon, as it is today.

North 8th Avenue runs from Lincoln Ave to Valentine St.

A representative street view of homes on North 8th Ave in Mt Vernon City, homes which are probably contemporaneous with the Johnston family. Comfortable residences, yes, but not banking money.

In the 1905 New York State census, we see the family living together again, but this time Lizzie Buttley is a “daughter”.

Image from the 1905 New York State census.

At the 1910 federal census the family was still in Mount Vernon City. A.C.’s dad had passed (Robert Johnston was 67 in 1900) and his mother Mary is now listed as the head of the household. Lizzie the boarder remained with them, but now she’s a “cousin”. Alfred, 25 years old, worked on his own account as a photographer by this time.

An image from the 1910 US Federal Census.

In the 1915 New York State census, we learn that A.C. has married a lady named Dorris who is a homemaker. Lizzie Buttley now lives with the newlyweds and is listed as a “roomer” rather than a cousin or sister.

An image from the 1915 New York State census, which describes A.C.’s living arrangements.

By the 1920 census, things start to get more complicated. Now A.C. is living in New York City with his English wife, Dorris, who at 33 years is almost the same age as A.C. They are both “Artists” who work in the “Pictures” industry. Lizzie’s out of their house, which is to be expected if her working life remained in Mount Vernon.

Image from the 1920 US Federal Census

Dorris Johnston is a fascinating figure. The same type of biographies which list A.C. as “the son of a banking family” describe Dorris as having met A.C. in school as an art student, i.e. when A.C. was enrolled in higher education at the National Academy of Design in New York. (Alfred Cheney graduated in 1908.) This romance story also appears to be an embellishment.

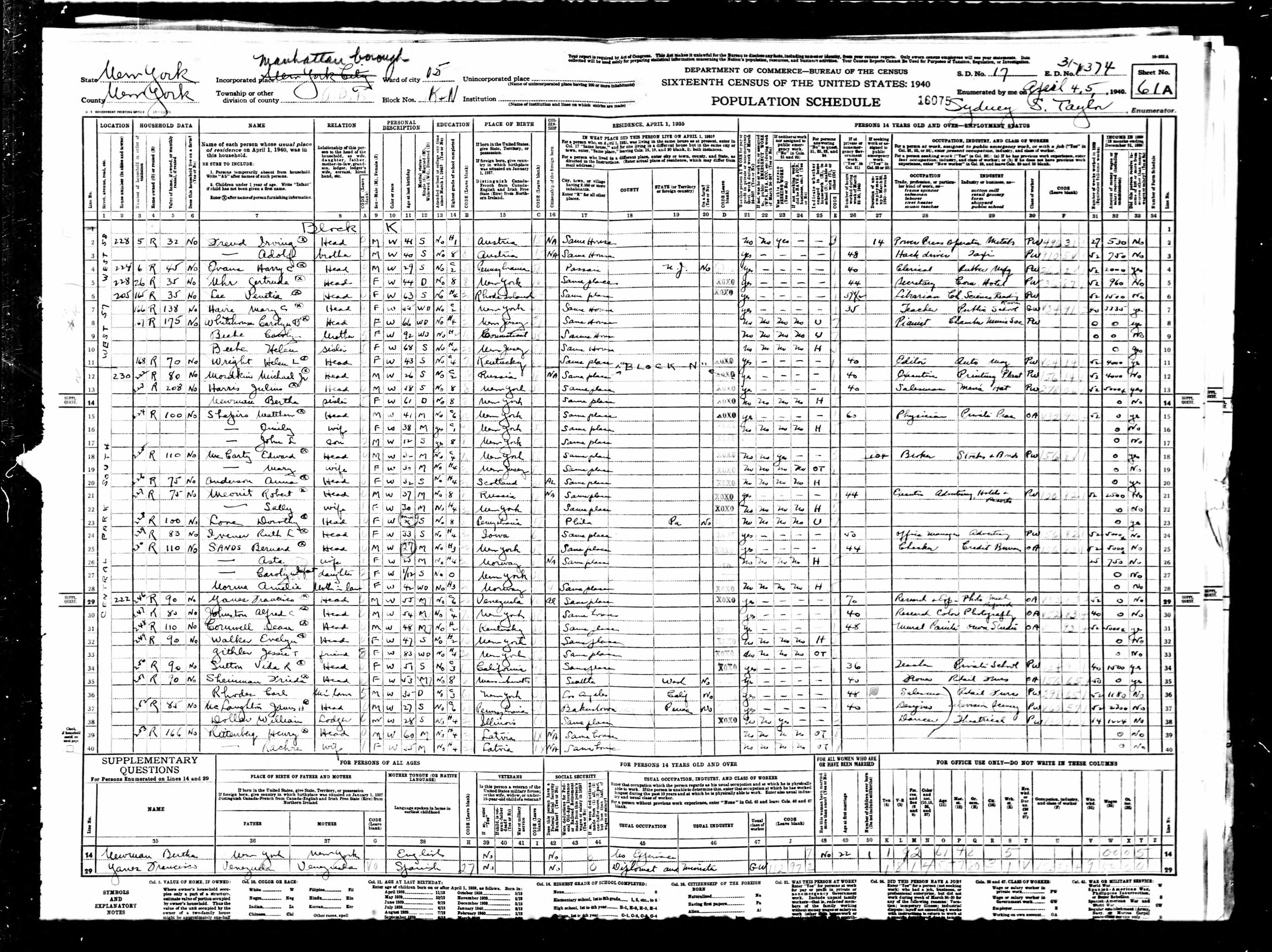

In the 1940 census, during which time Dorris and her husband were living separately, Dorris is listed as having no more than a high school education (“H4”, meaning she’d completed the fourth year of high school). She was never enrolled in higher education. This leaves how the pair met a mystery, and one cannot assume that opportunities were abundant for a foreign woman with the equivalent of a high school diploma. It’s possible that Dorris was among A.C.’s showgirl sitters (a number of these showgirls were English, I’ll talk about the Belascos in my next post) or that she met Alfred through another occupation which didn’t bear scrutiny to some (auto)biographer. Such a meeting would not be outside of A.C.’s character: according to collector Robert Hudovernik A.C. did go to his sitters for sexual favors and sometimes became expensively besotted.

An image from the 1940 US Federal Census, showing Dorris Johnston as head of her own household in New York City, New York.

The 1930s must have been a difficult time for A.C. and his wife. A.C.’s patron, Ziegfeld, had gone bust in 1931 and lean times were on the pair. If Alfred Cheney Johnston had been taking the type of pictures which traumatized teens like Edith May Leuenberger, he probably wasn’t fun to be married to. Intelligent guesswork aside, the Johnstons had lived apart since 1935 at least. While Dorris doesn’t list an occupation, in 1940 A.C. now says that he’s engaged in research into color photography. Oh, the possibilities!

An image from the 1940 US Federal Census that shows Alfred Cheney Johnston as head of his own household in Manhattan.

Happily, the couple were reconciled by the 1950 federal census. The Johnstons now lived about 40 minutes’ drive north of New Haven, Connecticut and list no occupations (both are in their sixties). Their neighbors on “Chestnut Tree Hill” appear to be in farming trades, so we can be pretty sure that they were occupying the (in)famous farmhouse, 136 Chestnut Tree Hill, where the secret stash of pornography lay waiting for either collectors or mobsters.

136 Chestnut Tree Hill Road, courtesy of historicbuildingsct.

So all this genealogical research begs the question: how did the myth of Johnston’s illustrious banking connections come into being? Even the preeminent Johnston scholar, Prof. David S. Shields, was under the impression that this banking story was factual. (I contacted him about this puzzle and he was good enough to confirm the “banking family” story. Back in January I sent him copies of the census records and am still waiting for his reply.)

The source of the “banking family” information is never given in any scholarly work. I believe that one missing piece to the puzzle will be provided by Johnston’s autobiography/biography I Never Wore Tights, which Johnston allegedly wrote with his “Connecticut neighbor” Gordon Bell. If Johnston doesn’t repeat the misinformation in this book, we can be pretty sure his publicists are chiefly to blame.

So where is I Never Wore Tights? Shields bought one copy of the unpublished manuscript at an auction and, to my knowledge, has not decided to make the book publicly available (or isn’t legally able to). In the meantime, Shields does provide us with one page from the manuscript and a transcript of parts of chapter two.

Interestingly, Shields doesn’t give much credit to Johnston’s/Bell’s recollection of the photographer’s time with Ziegfeld:

In 2011 I purchased one of the two surviving typescripts of Bell's memoir. The narrative alternates between passages evoking the general world of the American theater and the story of Johnston's establishment as a photograph. Below I have excerpted portions of Chapter Two bearing on Johnston's establishment as a major camera artist. While the story of Johnston's employment by Ziegfeld in Chapter One intermixes the factual and the imaginative in equal measure, the tale of how Johnston set up his first studio in Chapter Two has the concreteness of report.

It would be interesting to know which parts Shields thinks are “imaginative” and why. The census information does throw up a red flag for Johnston’s relationship with Bell, however. Shields explains the existence of the I Never Wore Tights manuscript as this:

Of all the versions of the legend [of Johnston’s time with Ziegfeld], the most elaborate is that recorded in an unpublished memoir, "I Never Wore Tights," of Johnston undertaken by his Connecticut neighbor Gordon Bell in 1935. Bell sought to use Johnston as a means of memorializing Ziegfeld's reign over American theatrical entertainment. Though its title announced that it would cover the period 1917 to 1934, the surviving typescript treats only the first five years of the announced span of coverage--roughly from "Miss 1917" to the triumph of "Sally."

Of course, the 1940 US census shows Alfred Cheney Johnston still living in New York City in 1935. The move to Connecticut happened some time after 1940. Just another mystery around the life of Flo Ziegfeld, I guess.

The “Napoleon III” Johnstons

Prior to my stumbling on the above census records, I’d wasted a lot of time looking into a prominent New England-derived banking family surnamed “Johnston” and a merchant family of that name on Washington Square. To the best of my ability to see, these two families would have been the ‘Johnstons’ who were prominent in NYC public consciousness circa 1910.

On reflection it occurred to me that this energy wasn’t entirely wasted, because by insinuating membership of this famous Scottish clan, either A.C. Johnston or his publicists were cashing in on a cachet which, presumably, appealed to the type of ‘art patron’ who’d dish out US $1,000 for a photo shoot with A.C…or even more money for one of his nudies!

By the standards of “Robber Barons” like Empress Sisi’s friends the Vanderbilts, the Napoleon III-Johnston family were old money. They were a wealthy Scottish family during Colonial times who were instrumental settling eastern Georgia. The Georgia ‘Johnston’ matriarch came from the Tracy family, an highly-educated lot who helped settle the Connecticut River valley in the late 1630s and were among the founders of Norwich, Connecticut, in 1660. Even when they moved south the Johnstons/Tracys maintained this CT connection. Beyond A.C.’s love of the state, the CT connection is interesting with respect to Early American counterfeiting, Mormon political power, and the Bonelatta Gang of Monroe, WI.

The Johnstons and Tracys were among the leading families of Macon but what really started the Johnstons on the road to NYC-level riches was the Georgia Gold Rush:

According to his obituary, [patriarch William Butler] Johnston profited from the Georgia gold rush that had begun with the discovery of gold in north Georgia in 1829. What followed was known, even at the time, as the “Great Intrusion,” with prospectors—acting “more like crazy men than anything else,” according to one eyewitness—flooded illegally into the Cherokee Nation beyond the Chattahoochee River.[18] The miners who swarmed through the north Georgia gold belt, which was centered around Dahlonega but stretched from McDuffie County on the east to Carroll County on the west, often sold their gold to middle men, like Johnston, who in turn would convey the raw gold to the Philadelphia mint for conversion into assayed bullion. While private mints were established in Gainesville and Milledgeville in 1830 and 1831, both were closed in less than a year and substantial profits were possible for those, like Johnston, who could afford to buy the miners' gold and convey it to the Philadelphia mint. As a jeweler, he would also have had other contacts that could have made gold trading especially lucrative.[19]

By the time the U.S. mint was established at Dahlonega in 1838, which eliminated many of the opportunities for middlemen to turn a profit on the miner's gold, Johnston had already made enough money trading in gold and jewelry to begin his career in banking and, perhaps, investing in the railroads that were beginning to be constructed in the state. In 1837, he helped to organize the Ocmulgee Bank, which failed in November 1842 while he was president. Johnston turned failure into success when he purchased the assets of the bank and, after ten years of litigation with its creditors, netted over $80,000. According to his obituary, this was his first successful large-scaled financial venture. Christopher C. Memminger worked as his attorney during this affair and, as Treasury Secretary for the Confederate States, no doubt played a role in Johnston's appointment as a depositor for the Confederate Treasury during the Civil War.[20]

Johnston’s business ventures suggest he was a model for Duke family investment strategy. In the 1850s, William Butler Johnston spent a lot of time in New York City, but his investments were in and around Georgia. Besides investing in Macon’s first railroad and the ‘Central Railroad and Banking Co.’ which connected Augusta, Savannah, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York, Johnston got in early on public utilities: gas, water, with a sideline in ice. Like all good bankers, Johnston also invested in insurance companies including the Hartford Fire Insurance Co. and, in 1869, the Cotton States Life Insurance Co. What’s more, the defeat of the South in the US Civil War didn’t stop Johnston’s business ventures one iota. That’s kinda weird because this NYC-habitué managed the South’s war chest.

How could this be? The Johnston House historian at Tommy H. Jones enlighten us:

When the secession crisis broke out in late 1860 and a state convention was called to decide the question, Johnston was, according to his amnesty request, "opposed to secession and did all he could for the Union Cause, giving his influence and vote for the Union candidate to the Convention." No doubt this was true, yet when Georgia did secede in January 1861, Johnston "quietly submitted under pressure as all his interests were in the State and it seemed to be his only alternative."[25]

It appears that Johnston adjusted quickly to the new realities. In late July 1861, serving as president of the Macon Chamber of Commerce, he issued a call "to the Merchants, Bankers, and others of the Confederate States of America to meet in Mass Convention, in the City of Macon, on the 14th day of October next." The purpose of the convention was to devise some system of international credits to replace that which had been disrupted by secession and war.[26]

In 1862, Confederate officials appointed Johnston agent for the Confederacy's purchase of and loans on cotton. The next year, the Confederate Treasury, under Johnston's old business associate C.C. Memminger, established a depository at Macon and Johnston was appointed receiver of deposits. This position, states his obituary, was gained "at the unsolicited recommendation of the Georgia representatives in Congress." There is a legend about the Johnston-Felton-Hay House that Johnston kept the Confederate gold in the "secret room" off the main staircase. Mrs. William H. Felton Jr. (1893-1985) denied this story when interviewed in 1980, but remembered a large safe in the basement wine cellar that, in 1915, still contained some Confederate paper money.

Front entrance to the Johnston-Felton-Hay house.

A side view of the Johnston house in Macon, GA.

A sumptuous interior from the Johnston house. I think I found where all that Confederate gold was hid.

A Pro-Yankee banker was put in charge of Confederate finances? It appears that from the very start of the Confederate secession movement, some were willing to give more than others.

In 1865, Johnston was elected president of the Central of Georgia Railroad and Banking Company with the principal task of raising money to re-establish the war-ruined railroad. In New York City, Johnston was able to secure loans of over $1,000,000 to rebuild and equip the railroad. Samuel J. Tilden, then a relatively unknown attorney but later Democratic presidential candidate, prepared the mortgage contracts for those loans. By the summer of 1866, the Central of Georgia was back in operation; his task complete, Johnston then retired as its president, although he continued to invest in railroads. In 1870, Johnston was part of the syndicate led by ex-Gov. Joseph E. Brown that secured the first private lease of the state-owned Western and Atlantic Railroad. That lease was the source of a major scandal in Georgia during the early 1870s.

Goetz aficionados will remember “Samuel J. Tilden” as the name Monroe’s likely arch-madame Almira Humes gave to her dog. Almira was a staunch Republican and Grant supporter, after all, whore-house operators benefited from the Bonelatta Gang crime bonanza too. (And it’s probable that her money, at least in part, started Arabut Ludlow’s National Bank.) It seems that the Confederate States’ banker figured out how to make the “Reconstruction” work for him, just like Lincoln’s supporters did.

What was going on? Whatever William Butler Johnston was doing in NYC in the 1850s might provide some sort of answer. Johnston was well-connected in NYC social and diplomatic circles, for instance, he hosted English novelist William Makepeace Thackery in 1855. On a similar note: Johnston met his wife, Anne Tracy, not in Georgia but on one of his NYC trips in 1851. The following describes the newlyweds’ European connections in 1852:

The Johnstons' diplomatic introductions also gained them invitations to various balls and other functions. On 3 January 1852, they went to “a grand ball, given at the Hotel de Ville by the Prefect to Prince Louis Napoleon, in honor of his election” to the presidency. In fact, the prince, who had been elected president in 1848, had staged a coup in December 1851 which would lead to his coronation as Emperor Napoleon III (1808-1873) in December 1852. Three weeks later, on 24 January 1852, they “went in the evening to a grand ball given by the President at the Tuileries. A very magnificent ball, but a terrible crowd... Louis Napoleon is quite a small man and not handsome.”

On 29 January, they left Paris for Avignon, Marseilles, and Nice, where they spent the first week of February. By the seventh, they were in Genoa where they continued sight-seeing and shopping… From Genoa, the Johnstons traveled to Florence and then to Rome, where they spent the late winter and early spring of 1852. There much of their time appears to have been taken up with visiting studios and galleries.

The Italian art market at this time was a shady affair which attracted the best of British and Imperial German espionage agents: Italian art “soft power wars” would reach something like a crescendo between these two powers in the 1890s. I’d like to point out that the Johnstons’ activities took place nearly 50 years prior to Henry James’ 1904 glamorous reflection on fin-de-siècle American art-collecting millionaires in The Golden Bowl.

The Washington Square Johnstons

Henry James makes a nice segue to the other family contending for A.C.’s inspiration. Compared to the “Napoleon III” crew, The “Washington Square “Johnstons were recent immigrants to NYC, having alighted in 1804, but they quickly made a name for themselves as merchants. Since wealthy merchants often got into investment banking, I couldn’t rule out the possibility that these Johnstons were the ‘bankers’ A.C. was shooting for.

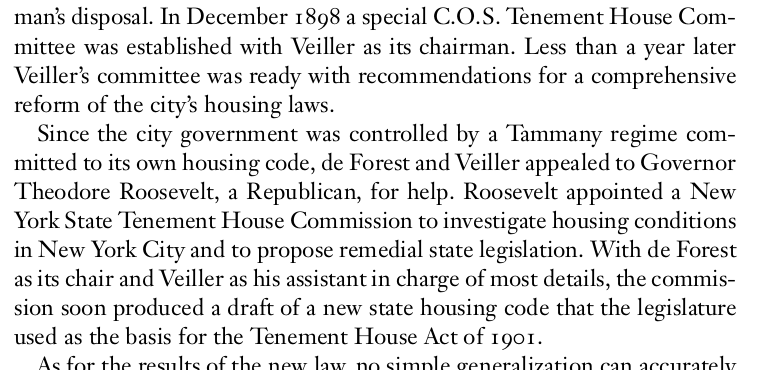

In many ways the Washington Square Johnstons, “Old Money” compared to people like the Vanderbilts, were far more artistically influential than the Napoleon III Johnstons. They were original sponsors for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, alongside their conservative Washington Square neighbors/in-laws the De Forests. The following excerpt is from Inside Greenwich Village: A New York City Neighborhood 1898-1918 by Gerald W. McFarland:

The interesting thing about Washington Square is that it provided a natural boundary to the red-light-district-creep from which “400” landlords like the Livingstons profited. (Other wealthy NYC bordello-landlords included American Tobacco Company aka Duke investors like the Lorillards.) According to McFarland, these Johnstons were house-proud and not about to let tenements overtake their neighborhood.

We shouldn’t be too surprised, therefore, to find that Johnston-patriarch Robert de Forest was a leader in the “scientific charity” movement and Housing Tenement Reform movement which Teddy Roosevelt used as a political stepping-stone. McFarland describes Robert de Forest’s philanthropic work:

That, readers, was Teddy Roosevelt’s big chance:

The Galician Network based their organized sex trade networks in these tenements, and Teddy could use his influence to protect this valuable vote-harvesting/creating “machine”. Housing Tenement Reform was also the big chance for William Wesley Young and his partner-in-crime Davis Edward Marshall.

My point, readers, is that the “Napoleon III” Johnstons and the “Washington Square” Johnstons looked like everything glamorous, urbane, rich and therefore good to men like Dolph Eastman of Educational Film Magazine, or hangers-on to the Duke family, etc. etc. (If you’d like to know a bit more about the psychology of these people, please see my post Liquor-Men to Movie-Men.) That A.C.’s promoters, or A.C. himself, might lie to associate the photographer/pornographer with this old clan played into new NYC money’s insecurities about not being “400”.