Arabut Ludlow, Bertha Honoré Palmer and Flo Ziegfeld

“Mr Bond, they have a saying in Chicago: 'Once is happenstance. Twice is coincidence. The third time it's enemy action'.”

— Ian Fleming, Goldfinger

One of the running themes of this website is that British Intelligence— the Redcoats— did not leave US shores after 1783. This post will build on that theme by examining the social connections between Monroe, WI’s founding banker, Arabut Ludlow; Chicago’s 1871-1910 power-couple Bertha Honoré Palmer and her husband Potter; and finally Flo Ziegfeld Sr (dad of the sex show entrepreneur).

A little context to these names: we met Arabut Ludlow before as the patriarch of the family who financed Monroe movie-man Leon Goetz, and also as a beneficiary of Almira Hume’s likely brothel. Ludlow’s bank thrived over the period in which Napoleon Bonaparte Latta used Monroe as home base for a nation-wide counterfeiting ring (1857-71), a ring that was sponsored by the Lincoln administration. These counterfeiters specialized in US Treasury $500 bills as part of Lincoln’s strategy to finance the US Civil War at his political opponents’ expense.

According to Monroe’s oral historians, Arabut Ludlow and Potter Palmer were good friends from at least the 1850s. I would like to point out that the 1884 history of Green County— a book overseen by Arabut himself— makes no mention of the friendship (or much about Arabut’s life, for that matter). Ludlow wanted to portray himself like a force of nature, a financial presence in Monroe which predated everything else.

There are no letters, diaries or other first-person documentation of the friendship. E.C. Hamilton, a prolific local historian in the 1970s, describes the friendship in more detail but fails to provide his sources. Hamilton was involved with our local newspaper, so he knew people who ought to know if the friendship actually existed. Hamilton states that Arabut Ludlow and Potter Palmer became friends as frontier merchantmen.

There are problems with this story. First of all, Potter Palmer was in an entirely different class to Arabut Ludlow. Ludlow was a frontier peddler in the 1840s who suddenly made a great deal of money in the 1850s. Ludlow worked out of a rough-and-tumble mining town when Potter Palmer sold fine goods from a storefront to aspiring Chicago ladies. Whatever Ludlow had before Bonelatta came, Ludlow got by trekking through woods and rivers where rogue bands of Indian bandits still killed settlers (read more about Land Pirates here). On the other hand, Palmer— by all accounts a passive sort of man— set up shop with his father’s money in a far more comfortable situation, not unlike the scene below. These were two different types of men.

South Water Wholesale District, late 1860s, before vanishing in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

Besties: Arabut after striking rich in the 1850s.

Besties: Potter Palmer, date unknown but probably after 1865.

However, there were also factors which may have united the pair. They were both merchants to the Western Frontier who used Chicago as a base. They were also New Englanders: Ludlow was an orphan from a backwater in Vermont, while Potter Palmer came from a Quaker family in Albany County, New York. In addition, Ludlow had information Palmer needed: he was an old hand in the Wisconsin Territory between Madison and Chicago (working this region from 1838) whereas Palmer found his way to Chicago in 1852, having failed in business back East.

I’m inclined to believe the Ludlow-Palmer friendship existed. Be that as it may, the earliest reference to the friendship I have found is a newspaper article in the Monroe Evening Times from 1946. I’ve found a far earlier connection between Arabut Ludlow and Potter Palmer’s wife, Bertha Honoré.

In 1878, the Chicago Tribune reported that Arabut Ludlow was involved in a legal dispute over a parcel of land across the street from Bertha’s father’s compound: the luxuriant ghetto of Chicago’s “Kentucky Colony”. I would compare Ludlow’s situation to that of the fellow who owned the lot next to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue as Peter L’Enfant began drawing up his city plans.

Chicago Tribune, January 21, 1878 page 8.

“Block 1, 2 and 3 of the Assessor’s Division of the East half of the South East quarter of sections 18, 39 and 14” is a land surveyor’s description that is still used as a reference in Chicago’s taxation maps, the “Sidwell Maps”. The image below shows how Ludlow’s property (green highlight) relates the compound bought by Henry Hamilton Honoré on behalf of a network of rich Louisville, KY families who wanted to relocate en masse in 1853-55 (purple highlight). These families were clannish, and were looking for a sort of contiguous ‘base’ from which to rebuild their lifestyle back in Louisville— even down to the “plantation” style of the homes and adjoining farms. Needless to say, these are huge tracts of land.

2021 Sidwell Maps number 1717E superimposed onto 1718H. (Their orientations on paper are slightly different, which is why they don’t perfectly align.) The purple location is described as “SUB. (by Henry H. Honore) of Blk. 40 of Canal Trustee's Sub. (see "A"). Ante-Fire”. The fire happened in 1871. Ashland Ave used to be named “Reuben Street”. Ludlow’s 1878 property is the green block across Ashland Avenue.

Disclaimer: I cannot be sure that “Arabut Ludlow” in the newspaper above is the same “Arabut Ludlow” of Monroe, but the 1870 census only lists one “Arabut Ludlow” in the Madison-Chicago axis. Individuals wealthy enough to invest in that amount of land were rare. I’m confident that we are dealing with the same man.

Around 1867, Henry Hamilton Honoré’s family bought another home on Michigan Avenue (Pine Street back then) and we don’t know how much, if any, of Honoré’s original Reuben Street development was still owned by him. (Though selling would undermine the effectiveness of his “base”.) We do know that it was typical for rich families living in city centers to have food from their rural estates shipped in: the Reuben Street property would have fit this “rural” description. The Honorés collected a great deal of property on the land which became “post-fire” Chicago.

In addition, we don’t know how many years prior to 1878 (if any) Arabut Ludlow owned/was invested in the huge tract of property across the street. The article states Ludlow brought suit to seize the land after the defendants’ failure to repay a mortgage on it. (Note Ludlow personally brought the suit, suit was not brought by his First National Bank of Monroe.) This is a strange situation which begs further investigation. Even for a man like Ludlow the defunct mortgage represents a large number of eggs in one basket and Ludlow wasn’t an idiot.

We can say that there were few surveys of Ludlow’s land prior to the 1871 fire, after which a flurry of development started. This frames Arabut Ludlow as a post-fire re-developer like Palmer and Honoré: but would Ludlow make such investments under the glare of the Secret Service’s Bonelatta investigations in 1871? Arabut would certainly have had cash on hand after the war (1865), but by the time of the Bonelatta investigations (carried out by Chicago’s Treasury office) he would have been cautious about splashing out— to do so would have tried President Ulysses S. Grant’s protection. The chances are good that Ludlow was invested in Chicago real estate before the fire: he had better reason than most to understand war-time inflation and the value of land. We don’t know how the fire affected the Secret Service’s investigations.

These questions would all be academic but for one fact which makes it highly likely that Arabut Ludlow did know the Honorés, and knew them quite intimately:

The same engravers who worked with Bonelatta and made Arabut Ludlow a rich man in Monroe, WI were busted for counterfeiting in the Louisville-Cincinnati region over the 1853-55 time period. The Kentucky Colony relocated from Louisville to Chicago over the 1853-55 time period. The OH-KY counterfeiters (engravers, distributors, etc.) were so well protected in KY politics that Cincinnati detectives (not Louisville ones) had to be used to conduct the investigation. I remind readers that authorities didn’t touch the top men from the Bonelatta crew, either.

What are the odds that Arabut Ludlow would end up across the street from these clannish émigrés after having taken up with their homeland’s most notorious engraver a few years after that engraver’s disgrace?

“Well Caluculated and Intended to Deceive” read Joseph Carlos Marin’s study of the Louisville-Cincinnati counterfeiting ring and the policing innovations that undid them.

Within 25 years of relocating to Chicago, the “Kentucky Colony” had positioned themselves at the heart of the city’s corrupt Democratic Party, which was largely financed by prostitution in the ‘Levee’ district. By the 1890s these families had mastered the use of political violence to control the city’s nascent socialist movement. The political “face” of this clan was the Harrison family, while its moneybags was Henry Hamilton Honoré.

“Kentucky Colony” men: Mayor Carter Harrison, architect of Chicago’s corrupt “Democratic Machine” and the deadly “Haymarket Riots”.

“Kentucky Colony” men: Henry Hamilton Honoré who, along with his son-in-law Potter Palmer, was the true “Lord of the Levee”.

It’s difficult to overstate the damage that the “Kentucky Colony” did to Chicago’s developing governance systems. Here’s a quote from Erik Larson’s Devil in the White City describing Mayor Carter Harrison’s political philosophy:

… Carter Henry Harrison, a former mayor who, with four terms already under his belt, was again running for office. When Harrison appeared… the crowd roared a welcome, especially the Irish and union men who saw Harrison as a friend of the city’s lower classes. The presence of Burhnham, Root [Columbian Exposition architects] and Harrison beside the Temperance stone was more than a bit ironic… The city’s stern Protestant upper class saw him [Harrison] as a civic satyr whose tolerance of prostitution, gambling, and alcohol had allowed the city’s vice districts, most notably the Levee— the home of the infamous bartender and robber Mickey Finn— to swell to new heights of depravity. [p 57]

Even his opponents recognized that Harrison, despite his privileged roots, made an intensely appealing candidate for the city’s lesser tier. He was magnetic. He was able and willing to talk to anyone about anything and had a way of making himself the center of any conversation. “His friends all noticed it,” said Joseph Medill, once an ally but later Harrison’s most ardent opponent, “they would laugh or smile about it, and called it Carter Harrisonia.” [p 213]

Like any con-man or prostitute, Carter Harrison believed whatever served his interests at the time and was as willing to have police beat protestors as he was to instigate riots himself. He fought against the Democrats as much as the Republicans and at times both parties were united against him: both parties lost. Harrison didn’t need either party, because he controlled Chicago’s voting systems through organized crime, the foundation of which was prostitution. In his book The Gambler King of Clark Street, historian Richard C Lindburg describes how one of Harrison’s crime-world lieutenants, Michael C. McDonald, ensured the vote in his fiefdom, which included voting district ‘Ward 1’:

Endorsed and supported by the powerful liquor lobby and ethnic fraternal societies organized to defend the saloon trade against Prohibition and blue laws, McDonald’s “ward heelers” were deployed across the city to organize the voters and seize control of the courts, the office of city hall, the bail bondsmen, the police and fire departments, the Cook County Hospital, the sheriff, and wherever else opportunity lurked to plunder the city treasury and acquire “boodle.”

McDonald lived near the Kentucky Colony on Ashland Avenue and knew Carter Harrison growing up:

Thus, an anti-temperance, anti-reformist zeal was championed by McDonald and a rising tide of Irish Roman Catholics, German immigrants, and day laborers who enjoyed their “continental” Sundays in the city’s beer gardens and after-hours visits to the downtown gambling resorts. The young roughs living elbow to elbow with gamblers and the purveyors of the vice trade in the poverty and squalor of economically depressed neighborhoods acquired the necessary survival skills by cultivating important political connections with key operatives in the saloon trade opposed to notions of “good government” and civic reform. The embryo of modern Chicago organized crime and its various subbranches was spawned in the decades these men rose to power.

What Harrison and capos like McDonald— McDonald wasn’t the only one— were doing was weeding out responsible or unreliable members of the Democratic party and replacing them with criminals who the “Kentucky Colony” could rely on. Sexual ‘kompromat’ and gambling debts were (are!) two tools used to this end. Readers may see the genesis of the struggle between Leon Goetz and law-abiding Monroe in Chicago’s “Blue Law” fervor. Lindburg, p.6 :

By the 1870s, the party of Jackson had deteriorated into a tool of clout-heavy “saloon bosses” from the large urban areas wedded to protecting the taverns from Sunday-closing legislation, the brothel keeper from the sermonizing crusades of the Salvationists and blue bloods, and the faro dealer [gambling] from taking up space in the city bridewell.

An examination of big-city Democratic machines in Baltimore, New York City, Trent, New Jersey, and San Fransisco during this time reveals highly organized syndicates for plunder and graft that grew rich by holding office through firm control of patronage, the withholding of taxes and revenue, the contracting of new loans to pay current municipal expenses, and the protection of the whiskey sellers and gambling interests that brought them to power…

Journalist Bruce Grant and Washington D. C. radio commentator Earl Godwin, looking back on a century of temperance agitation, correctly noted in 1936 that “the revulsion of public feeling against the saloon was the result of the persistent villainy of the lower element in the liquor trade, which attempted to control politics and mix the drink trade with commercialized prostitution and other immoralities.”

A Gilded Age “liberal” generally opposed the imposition of blue laws. The liberal subscribed to the pragmatic belief that it was not governments place to legislate morality or deny workers the right to gamble or socialize in the manner they had become accustomed to in the Old World. “No Blue Laws for Chicago!” remained the constant refrain of the Carter Harrison Democrats-- the political “Bourbons”-- around election time as they pandered to these attitudes in order to maintain and perpetuate local control of patronage.

I remind readers that Abraham Lincoln himself was a “whiskey seller” in a rough logging camp in Illinois (and he lied about it). Lincoln’s most rabid cheerleader in Monroe, Almira Humes, ran our “whiskey hotel” by the train tracks. Learn more about the humanitarian crisis these pimps/alcohol retailers created in Southern Wisconsin in my post on the Tillie Bergsterman Murder.

By the time of his struggle for mayorship during the 1893 Columbian Exposition, Harrison decided he would no longer tolerate any independence from the Democratic party and lay the foundations for Chicago’s centralized “Democratic Machine”, the organized-crime machine, which 140 years later has largely destroyed the city, particularly State Street. Harrison’s con-job is is a very old one which cynically exploited socialism and narrow ethnic interests from day one.

But how was this small knot of Kentucky immigrants able to wreck so much havoc in such a short time?

Chicago was a strange place even in the 1850s: the city was a locus for interests unaligned with law-abiding populations on the East Coast, in Southern States, and to an increasing extent the prairie farmers who developed the land around it. Chicago drew its spirit from whatever happened to be swimming in the Mississippi, or lurking in the border waters of the Great Lakes. What do I mean by that? Consider this description of pre-Civil War Chicago from Lindburg, [p 2]:

Unrefined and increasingly bifurcated, Chicago in the antebellum period was a city of puzzling contradictions. In the one hand, its great commercial houses, its halls of justice, and its municipal offices were filled with Northern men and abolitionists scheming and contriving to deliver the state’s favorite son, Abraham Lincoln, to the White House… but at the same time, the city was awash in “Copperhead” [pro-South] sentiment and rumblings of sedition.

… The city was full of “bummers” (drifters, cardsharps, bunko operators) and Southern refugees formerly engaged in the Mississippi riverboat trade, until the outbreak of war forced them to flee north to escape conscription in the Confederate Army.

This diverse and unsavory group of people agitated to install their own men at the heart of city politics… and politics makes strange bedfellows. Here’s a quote from Lords of the Levee, Herman Krogan and Lloyd Wendt’s economic/criminological history of Chicago:

The First Ward [Chicago’s central voting district] that “Bathhouse John” [John Coughlin, another capo like McDonald] desired to represent… was the nerve center of a city which at the beginning of the 1890’s was still a roaring, overgrown frontier town. Only fifty years before had the pioneers sloshed the mud from the harbors, ditched the Calumet River to reach the port of New Orleans, and strung great ribbons of steel [railways] to hitch up a tough new country to the… south tip of Lake Michigan. In the five decades they had fought pestilence and fire to erect a city which would dominate the whole New West, from the Golf of Mexico to Canada. They had struggled in the mud, defeated Eastern [East Coast USA] politicians and bankers who wanted their capital elsewhere, and crumpled frontier-town competitors to make Chicago the terminal of a vast, unbroken empire…

They had sent out business janizaries [sic] to capture the grain and pig trade [The Beef Trust] and chased the great Illinois Central Railroad [run by an old NYC financial consortium including the Livingston family] out of an Indiana terminal into their own front yard… When New York and Boston refused to deal with them, they had gone to Great Britain and Holland for money and they had even hatched a plot to trade with Canada and exclude the United States seaboard entirely until the outmaneuvered East finally came to terms.

I had to laugh when Wendt/Kogan described the Beef Trust as janissaries, I’m not sure they knew how right they were. Anyway, the core nugget here is that Chicago was never a patriotic city, it was a city that wanted to “get mine” and working with the British was the easiest way to do that in the later half of the 19th century. (In future posts I’ll show you the same thing was happening in Florida at this time.) A significant portion of Chicago’s population were driven there by 1) improvements in policing back East and in the South, as well as by 2) grassroots dissatisfaction with political corruption stemming from Freemasonry networks (The Anti-Mason Movement).

Displays of Power for the 1893 Columbian Exposition. Both this “Masonic Temple”, and the “Women’s Temple”, were celebrated in Columbian Exposition souvenirs. “Masonic Temple, State and Randolph Streets, Chicago, photograph c.1895-1915, J.W. Taylor, Chicago. Ryerson and Burnham Archives. Marshall Field & Co. is on the right.” Courtesy of Roger Jones.

Jones: “The Masonic Temple is considered one of [John Wellborn] Root’s three greatest buildings in Chicago, along with the Rookery (1888) and the Woman’s Temple (1892).”

Note the white building in the RHS foreground is Marshall Field’s department store, for which Potter Palmer was landlord. Chicago was a very small world.

“Woman’s Temple, Chicago, LaSalle and Monroe Streets, 1892, Burnham and Root, architects (demolished 1926) View from northwest. One Hundred and Twenty-Five Photographic Views of Chicago. Chicago: Rand-McNally, 1902, plate 9.” Roger Jones.

Financial irregularities involving this building resurfaced circa 1910 and landed Bertha Honore Palmer in hot water. The missing money almost exactly equaled the price of her initial Florida land purchase at that time!

The type of person running to Chicago was often sympathetic to British Intelligence for financial reasons, sometimes for illicit financial reasons. The feuding Freemasonry networks I just mentioned had synergies with counterfeiting networks that stretched across New England and Canada, as well as with the early Mormons. [See Secret Combinations, by Kathleen Kimball Melanakos. ] After the 1826 murder of William Morgan these masonic networks became politically vulnerable and, alongside pro-British counterfeiting networks and the Mormons, they moved westward.

The genesis of these mason-aligned counterfeiting networks lay in British military intelligence. In the 1770s counterfeiting was a British economic weapon. (Connecticut had the largest pro-British population of any state— this will be important.) Many Revolutionary War era counterfeiters ran to Canada or the hinterlands of New England after the defeat of the British. Monroe’s Jennings family is believed by our local historians to be among these Canadian refugees, while the family of Mormon leader Joseph Smith has been identified among this same counterfeiting milieu. Smith’s successor Brigham Young made aggressive (and illegal) attempts to outfit the British with American warships; while the son of Arabut Ludlow’s lackey, William Wesley Young, became a full-fledged British Intelligence agent around 1913. For Monroe, WI’s Mormon connection, please see posts listed here.

In short, Chicago was the 19th century’s inland “Port Royal” where jetsam from the Mississippi River and Great Lakes washed ashore. Potter Palmer and Henry Hamilton Honoré both washed in on the same tide and I’ll end this post by looking at these men’s background and how they birthed our “Ziegfeld” phenomenon.

Potter Palmer was the type of man who ran to Chicago having failed back East. His quick success in Chicago remains largely unexplained: the official story is that his department store succeeded because he offered shoppers various forms of credit, but if this was so profitable other merchants would have quickly followed him and extinguished his advantage. For “innovative” credit programs to have been a true advantage, Palmer would have needed larger, more robust credit lines than all his peers. (We know that after the 1871 fire, Palmer and Honoré were able to rebuild their empire with a staggering loan from J. P. Morgan’s Connecticut insurance company, CT Mutual Life Insurance Company.) Somehow, in just a few years between 1852-60 Palmer made the jump from frontier dry-goods salesman to that of a merchant who regularly traveled to France to source fashionable fabrics. The transformation suggests a third party.

The original George Peabody statue (from before 1890) outside the Royal Exchange in London. Peabody’s firm became “J. P. Morgan & Co.”. J. P. Morgan was the American face of a British financial empire

We know that J. P Morgan built “his” empire on the back of George Peabody, who is considered a giant of British finance. Where J. P. Morgan appears, August Belmont was never far behind, the most famous example of which being the “Morgan-Belmont Agreement” which “saved” the Cleveland administration. Here’s Encyclopedia Britannica on August Belmont:

At age 14 Belmont entered the banking house of the Rothschilds at Frankfurt am Main, and he later transferred to the Naples office. In 1837 he moved to New York and opened a small office on Wall Street, where he served as the American agent for the Rothschilds and laid the foundations for his own banking house (August Belmont & Company). He took an active interest in politics as a Democrat. From 1853 to 1855 he was chargé d’affaires for the United States at The Hague, and from 1855 to 1857 he served as resident minister there. Although he opposed slavery, he supported Stephen A. Douglas, the architect of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. After the American Civil War began, however, Belmont became a loyal supporter of Pres. Abraham Lincoln and exerted strong influence upon merchants and financiers in England and France in favour of the Union. He also served as chairman of the Democratic National Committee from 1860 to 1872.

This matters readers, because it is in precisely these “merchant and financier” circles where we find Bertha Honoré Palmer playing a ‘Jeffery Epstein’-role to Edward VII’s ‘Prince Andrew’ circa 1907, the magic year for the ‘international intelligence community’. This role will be the subject of my next post. In the meantime, the “British” half of the “British and Dutch” investors who saved Chicago from New York begins to come into sharper focus…

Whatever propelled Palmer’s initial financial success, his success —just like Arabut Ludlow’s success— came in a very short time over the 1852-1860 time frame. Allegedly, Palmer met the Kentucky Honorés in this ‘dry goods merchant’ period. The US Civil War (and those credit lines) made additional cotton profits easy:

When the Civil War broke out, he [Palmer] foresaw the need for cotton wares. He borrowed heavily from the banks [unexplained], crammed all the warehouse space he could rent with cotton and woolen goods, and in one fast operation bought up all the cotton held by A. T. Stewart, of New York; then later sold it back to him when the price of cotton soared. Most of it had never been moved from the warehouses. This new fortune was being built up when Bertha Honoré, by sheer chance, came into view and all at once became more important to Potter Palmer than the rising tide of wealth that was sweeping him into greater prominence.

That quote is from Ishbel Ross’s biography of Bertha, Silhouette in Diamonds, which was written with the oversight of the Honoré family in the 1960s. Why didn’t the Union Government simply commandeer Palmer’s NY cotton? Chicagology:

During the war, Mr. Palmer was unwavering and practical in his loyalty. He rendered himself specially serviceable to the Government by loaning it large amounts of money, undeterred by apprehension of failure or repudiation, and at the close of the war the Government was in his debt to the extent of over three-quarters of a million of dollars. For this he deserves the lasting gratitude of every patriot.

(Arabut Ludlow was an important part of this duplicitous war-time financing, see Fake $500 Bills in Civil War Wisconsin.)

Maybe Palmer did get all his cotton from US warehouses. I think it’s more likely that he went where everybody else in the world did once the US South went ‘off line’ as a cotton supplier: the Ottoman Empire by way of Salonica and London. For a few years during the US Civil War, the Ottoman cotton market provided a low-quality alternative to Southern cotton for Britain’s mills. This Ottoman trade provided economic opportunities for Austro-Hungarian subjects who were trafficking other things through Salonica [White Slave Trade], for example Sigmund Freud’s Birmingham relatives. In typical Galician tradition, the patriarch of this Birmingham Freud branch died by falling under a train.

Summer 2025 Update: Lincoln’s war time top intelligence heads, like Grenville Dodge, operated a massive Southern cotton smuggling operation through Chicago. It’s more likely Potter got his cotton through them!

One of the more horrific aspects to the US Civil War was the explosion of organized prostitution which followed Northern armies and laborers in particular. I addressed this in my post on Monroe’s journalist/Lincoln groupie/fake nurse Janet Jennings. Following this development, department stores, staffed by teen girls of humble origins, became a prime recruiting/grooming ground for Galician Gang pimps, and their less organized competition. [See Bristow, Prostitution and Prejudice.] Venereal Disease clinics, train stations and factories were other hot-spots.

At some period towards the end of the Civil War Potter Palmer made the decision to sell his department store to his partners Marshall Field and Levi Z. Leitner, but Palmer remained their landlord for many years thereafter. Many of the buildings celebrated through the Columbian Exposition cluster around the building Marshall Field’s rented from Palmer, not only the Masonic Temple but also the Central Music Hall, wherein Florence Ziegfeld Sr. ran his “music school”-cum-international talent agency.

Dr. Florence Ziegfeld’s music school premises, as celebrated in an 1893 Columbian Exposition souvenir booklet held by the Smithsonian Institution.

We know that the Honoré family and Potter Palmer were tight prior to 1865 because in 1862, when Bertha was 13 years old, it was agreed that she would marry the 36 year old Palmer. (The Honorés were living at the Ashland plantation at this time.) The honor was all Palmer’s, and throughout his married life he was subservient to Bertha and his in-laws, to the point where their initials, not his, were inlaid on the floor of his luxurious Chicago home, “The Castle”. Who were these Honorés?

Contemporary Chicago directories say that Henry Hamilton Honoré, a native of Louisville, KY, began to contemplate leaving his hometown in 1853 and finally did so in 1855. As I mentioned, the period 1853-1855 also coincides with the bust of a massive counterfeiting ring between Ohio and Kentucky, which included Louisville in its orbit. The Honorés were one of a handful of wealthy Louisville families who sold their plantations and moved to Ashland Avenue, Chicago en masse. One of these families, the Harrisons who were originally from Virginia, supplied two Chicago mayors and two US presidents.

Benjamin Harrison, the 23rd president of the United States, was a member of the same Harrison family who sent a branch to Chicago with H. H. Honoré. President Benjamin Harrison appointed Bertha Honoré Palmer as the female head of the Columbian Exposition, an economic spectacle decreed through an act of Congress. Bertha ruled the exposition with an iron fist.

The Honorés came to the American colonies as war profiteers following the Marquis de Lafayette in 1781. The patriarch, Jean Antoine Honoré, “engaged in the Mississippi riverboat trade” and was one of two men who really opened the Ohio River Valley to New Orleans. Jean Antoine Honoré thrived and grew into a “merchant prince” when mercenary/pirate Jean Lafitte controlled the mouth of the Mississippi River.

The Honorés settled in Oldham County, Kentucky which is just north of Louisville and a straight ride to Covington, the Kentucky-Ohio boarder terminal of the OH-KY counterfeiting ring. Oldham County is outlined in a dashed red line on the maps below. I remind readers that nineteenth century counterfeiters loved border territories where police jurisdictions changed easily or were fuzzy. Counterfeiters also loved fast transport via waterways: the river pictured is the Ohio River which meets the Mississippi at the southern tip of Illinois.

Oldham County, KY is outlined in red dash.

Oldham County on the route between Louisville, KY and Cincinnati, OH.

Oldham County, KY to counterfeiting terminus Covington, KY on the Ohio border by Cincinnati. Upright Cincinnati police detectives were the only reason this well-connected counterfeiting ring was busted in 1853-55.

The Ohio River Basin: The Ohio River provided an ideal thoroughfare for counterfeiters fleeing law enforcement and an unsympathetic public from 1830 onward. The Ohio joins the Mississippi at the southern tip of Illinois. The river is considered the boundary line between Midwestern and Southern states and connects Pennsylvania, Ohio, West Virginia, Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois, and Missouri.

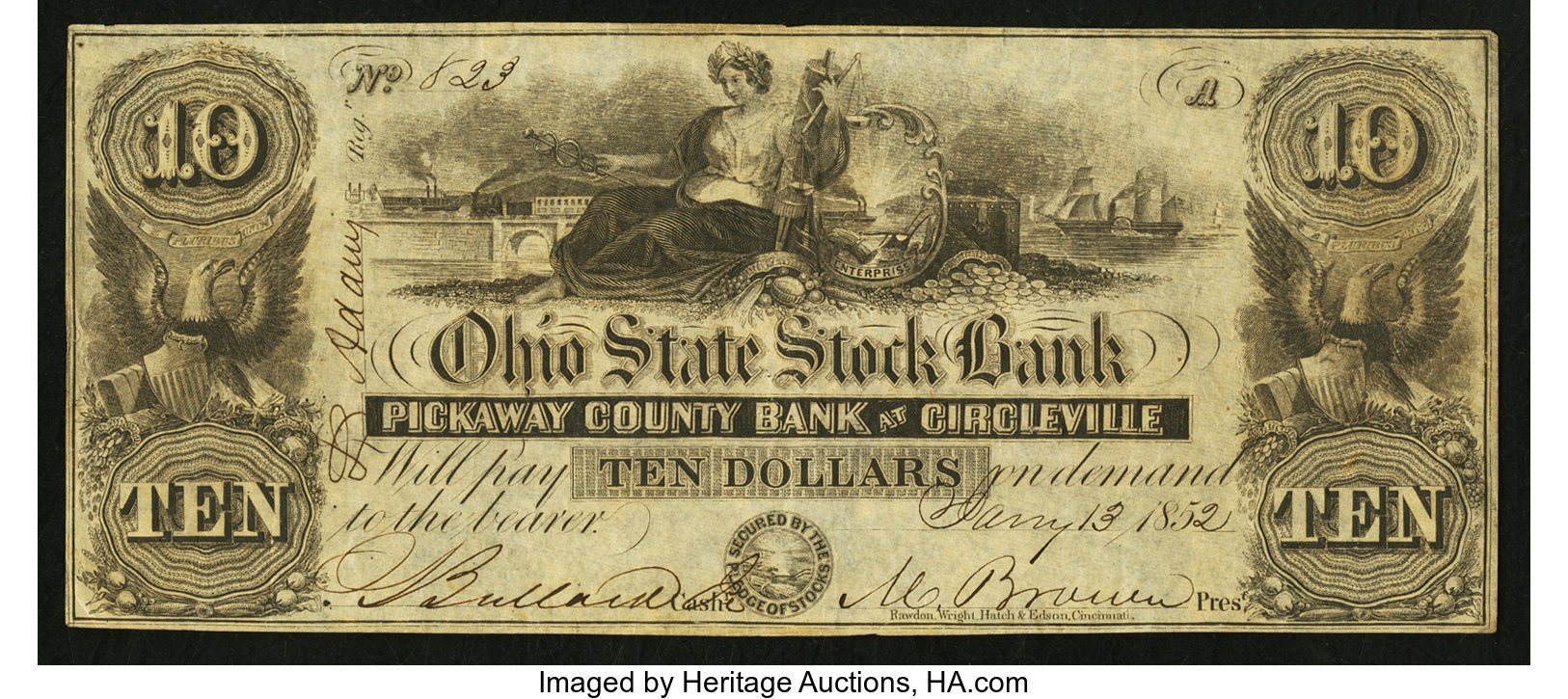

Prior to 1853, the OH-KY counterfeiting ring was so politically connected in Kentucky that it could not be touched by law enforcement. Therefore, Kentucky police asked Cincinnati, OH police for assistance. When the ring was unwound, detectives found that the forgeries were being produced by “Rawdon, Wright, Hatch, and Edison” engraving company employees, who also produced the legitimate version of the targeted banknotes. After the 1853 bust, this firm relocated to New York City and renamed itself the “American Bank Note Company”— the same company which supplied the Bonelatta crew with it’s engravers from 1857, at the latest. (And also the company the US Treasury used to print it’s “greenback” currency thanks to Lincoln’s treasurer Salmon B. Chase.) We know that the OH-KY crew had at least one ‘Ballard’ signing their fakes in 1852, and this could be the same Tom Ballard who worked with the Bonelattas in the late 1850s.

A fake 1852 Ohio State Stock Bank bill, signed by one “Ballard” and “M. Brown”. Daniel Brown was one of the most prominent counterfeiters working the Ohio River Valley. Counterfeiters worked in family groups.

The Ohio State Stock Banking system was made of a network of banks which mutually insured themselves through a stock-holding system, designed to mitigate against bank failures. Each member bank could issue notes, meaning most people using these bills would not have known if “Ballard” really was president of a bank on, say, the other side of the state. The counterfeiters targeted the OSSB system because it was well respected in New York City financial markets and stable.

The OH-KY counterfeiting group were a well-heeled bunch, a number of them professed to be doctors. The “break” for Cincinnati detectives came when the landlord of the Washington House Hotel in Covington contacted police because he was concerned how many men were visiting the room of one of his guests, George Kingsley, who was later convicted for counterfeiting.

No Honoré was ever convicted of counterfeiting, but isn’t the timing of their move to Chicago strange? “Strange” also describes the clannish way these Louisville transplant families behaved while building their luxuriant ghetto on Reuben and colonizing Chicago politics in less than ten years. Not only that, but within seven years of the move they’d already betrothed one of their children to a man tight with the North’s Bonelatta kingpin, who just happened to moonlight with the American Bank Note Company…

I will skip ahead now to 1893 when ‘power couple’ Bertha Honoré Palmer dragged her husband to the forefront of Chicago society via Kentucky Colony contact President Benjamin Harrison and the Columbian Exposition. The exposition was managed in order to advertise Chicago globally, though Congress intended it to advertise the entire USA. Bertha used it as a vehicle for self-promotion and this benefited her hangers-on, one of which was the father of Florenz Ziegfeld Jr., Dr. Florence Ziegfeld Sr.

Ziegfeld Sr. ran a music school and talent agency from the Central Music Hall next to Palmer’s “Marshall Field” department store building. Austro-Hungarian police identified international musical acts as primary trafficking vectors for the White Slave Trade. Department stores were grooming/recruiting hot-spots.

Chicago Tribune, February 5th, 1893.

Bertha knew Ziegfeld Sr. socially from at least 1891:

Chicago Tribune, December 4. 1891

Ziegfeld Sr. was contracted to develop a new theater for the Columbian Exposition, the Trocadero, for which he was able to recruit 200 international musical acts at the drop of a hat.

Chicago Tribune, October 16 1892.

These cultural acts included trapeze artists, and a strong man named Eugene Sandow, who Ziegfeld Sr’s son had found in a London sex show:

Chicago Tribune, June 14, 1893.

Much of the promotional work Ziegfeld did for the exposition was done in German Europe, where he had excellent contacts in the Prussian military and Viennese diplomatic circles since at least the US Civil War, when prostitution flourished next to barracks and hospitals. None of this promotion would have happened without Bertha’s blessing.

The Inter-Ocean, June 19, 1892.

Ziegfeld was even slated to become the “musical face” of the Columbian Exposition, even though his musical reputation was strictly local:

The Inter-Ocean, May 26th, 1891.

For those of who haven’t seen my work on Ziegfeld Jr. and the Theatrical Syndicate: Ziegfeld Jr.’s career with girlie shows was built alongside luminaries of NYC’s “Theatrical Syndicate”, which controlled US theaters until the rise of film. (The people who took over after Teddy Roosevelt et alia destroyed the Edison Trust were ‘graduates’ of the Theatrical Syndicate’s executive ring.) I’m talking about Charles Frohman, David Belasco, the Shubert Brothers, Otto Kahn and their inspiration, Sir George Lewis. The “Theatrical Syndicate” was built on Church of England money. Outside of the U.K., the Church of England (Episcopal) has long been used as a cover for British intelligence operations. The “Theatrical Syndicate” took its marching orders from the controllers of London’s theater scene. Read all about how they used Edward VII here.

After pumping Sandow through Bertha’s Columbian Exposition, Ziegfeld hitched his wagon to British Intelligence. To be fair, Bertha and Flo knew more than few shady people in Vienna and Berlin too… but that’s still “enemy action”.

—

Title image from Prohibition Cartoons by D.F. Stewart and H.W. Wilbur, Defender Publishing Company, 1904.

“Representing the liquor-traffic as an octopus is literally correct. It is indeed the devil-fish of our civilization, doing business, strange to relate, with the assent and consent of the Government, with just the merest disposition to occasionally try to nip a tentacle or put a drop of diluted blue vitriol on one of the monster’s ugly glands.

The octopus itself is scarcely sensible of the various guarded and indirect attempts to curtail its infamous, death-dealing effort. It is time reasonable people and responsible government stopped temporizing and trying to restrict and regulate this monster, with the idea that it can be made comparatively safe. While it lives it will draw to itself and devour some of the best life in the community.

Our national octopus can only be made to cease from troubling by plunging the sharp knife of Prohibition to the hilt into the seat of its vitality. In that process every citizen should have a hand.”