Leon Goetz in Florida

Until recently I’d been under the misapprehension that when Leon Goetz moved out of Monroe, WI for the second time he’d made a sort of break with his livelihood of twenty years. I thought he’d given up the movies for real estate. I’d been missing the point, however. By 1935 opportunities for people connected with the Roosevelt family’s political machine had flipped from film to Florida real estate, therefore (in a sense) Leon was doing what he’d always done. This post explains how I arrived at my understanding.

The 1931 Goetz Theater, located at the southeast side of Monroe, WI’s downtown “Square”, was completed by entrepreneurial brothers Chester and Leon Goetz. The brothers were investing in an independent movie house at a time when the new ‘Hollywood Majors’ sought to buy movie theaters en masse to ensure playing venues for their product. These Majors, under the acronym of the “MPPDA” (Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America), sought to recreate their own version of the Edison Trust, but with the support of the White House and the military.

Instead of crushing this new ‘monopoly’ (it was, in fact, an oligopoly like Edison’s), the FTC and Justice Department were more interested in coaching the MPPDA on how not to obviously violate the Sherman Anti-Trust Act. The MPPDA’s only real adversaries were, ironically, independent theater owners like the Goetz Brothers.* Beginning in the 1920s, the Majors sought to buy up independent movie theaters through a network of subsidiary companies: a key tactic in their new monopolistic strategy. The financing for this tactic came from NYC investment firms like Otto Kahn’s Kuhn, Loeb & Co. and Goldman Sachs. What Washington got in return was Hollywood’s cooperation in propaganda campaigns.

Chester and Leon had been burned in 1927 when they sought to invest in Milwaukee theaters just as the Majors busied themselves putting every exhibitor they couldn’t buy out of business. An over-developed market in Milwaukee made this ‘shake out’ particularly dangerous for smaller operators. 1927 was the beginning of the end of the theater empire which the Goetz Brothers built in South Eastern Wisconsin. By 1931 it appears that the new Monroe Theater was the only theater left, but I cannot be sure of this.

What I do know for sure is that Chester Goetz was struggling. In 1928 he was sued by the Central Wisconsin Trust Company for $12,000 plus attorney fees, which was the principal of a loan he’d taken out in March 1921— during the production time of Edith May’s movie— and on which he’d only ever paid the interest. Judgement was made against Chester, who did not show up to defend himself.

When Leon Goetz sold his stake in Chicago film pornography company “Road Show Pictures, Inc.” in 1931, Leon may have provided key capital for him and his brother to retrench in their hometown. Certainly, in 1940 when the State of Wisconsin sought over $25,000 in unpaid taxes from Leon, they garnished Chester’s assets under the belief that what Chester owned was, at least in part, due to Leon’s money. (Records for this case are one of the vanishingly few criminal court cases which are still part of the denuded Green County archives in Platteville.)

However, by 1940 Leon Goetz was long gone from Monroe, WI. Leon had moved to Marathon, Florida to participate in the property boom following the State of Florida’s 1935 purchase of the bankrupt “Overseas Railway” from New York banker John D. Rockefeller and his Standard Oil partner Henry Morrison Flagler, the “Father of Miami”. (Like a number of the men around the Mayflower Photoplay Corporation, Flagler was the self-made son of a Presbyterian minister.)

Thirty years before, Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler’s investment company had decided to build the “Florida East Coast Railroad” with a line from Homestead to Key Largo via Card Point and Jewfish Creek.

An image of the first stops of the Florida East Coast Railway. From what I can tell, the line did not enter the Keys from Card Point, but hugged the coast up to Card Point, from which it curved inland slightly before crossing the sound and entering North Key Largo at Jewfish Creek, then carrying on down the keys.

The railway, known as “Flagler’s Folly” cost around $50 million to build over the 1905-1912 period. Together with other network lines it connected New York City to Havana, Cuba via Florida’s Key West, a deep water port that was supposed to boom after the shenanigans surrounding the construction of the Panama Canal, which the US built and gave away over roughly the same period (1904-1914). According to historian Alice Hopkins, most of the laborers who built the railway came from New York City’s “Skid Row”, stomping ground of the Galician network and Theodore Roosevelt’s political heartland. Railway developers’ practice of giving railway employment to politically favored groups was a long-standing practice established in Central Europe; in turn these vassal rail employees were a source of valuable intelligence and a political bulwark against dissatisfied locals. Ex-military men were often favored for these jobs.

Image from Alice Hopkins’ paper, “The Development of the Overseas Highway”. “Map from timetable, Florida East Coast Railway Company, 1 July 1917, Historical Association of Southern Florida.” The rail line is the heavy black line that snakes its way down the east cost and into Florida Bay.

The Panama Canal was a pet project of NY political magnate Theodore Roosevelt, who just four years prior had ‘liberated’ Cuba from the Spanish, making it a haven for Galician network slavers and election fraudsters like the Soviner Brothers. (For more on Monroe-native William Wesley Young and Roosevelt’s “rough riders”, see my post on Young’s British Intelligence work during WWI.) Flagler’s Folly was just one more way that the Roosevelts’ ‘in crowd’ sought to profit at the public’s expense.

Teddy’s friends did not ignore lessons from European history. American WWI veterans, fresh from their new film-based venereal disease ‘education’, were employed to maintain Flagler’s Folly as an artery to Roosevelt’s balmy sex-trade hub. In the 1930s the US Federal Government began a policy of sending “troublesome” WWI veterans to work on roads servicing the struggling railroad, at least 327 of whom died (along with 119 civilians) because of poor safety planning during the 1935 “Labor Day Hurricane” which ended the folly for good.

Images above come from RareHistoricalPhotos.com, they date from 1937-50 and depict entertainers in Havana. The photos are held in the The Life Picture Collection of the Smithsonian Institution.

Flagler’s $50 million investment was sold to the State of Florida for something around $640,000. These were very tough times for the regular citizens of Florida, who had been hit harder by the Great Depression than we were in rural Wisconsin. Hope came in the form of Franklin Roosevelt’s “New Deal” plan, which began funding extensions for the road which ran parallel to Flagler’s old train track:

In 1935, the histories of the Overseas Highway and the Overseas Railway became one. The Labor Day hurricane had hit the weakest, most vulnerable spot of the railroad. Estimates to repair the destroyed embankments ran into millions of dollars. 34 Even if a loan could be secured, it would seem like throwing good money after bad. Passenger service to Cuba was being handled very smoothly out of Miami. Plus, Pan American Airlines now had a special plane service between Miami and Key West. The day of the Overseas Railway had passed; that of the Overseas Highway had barely begun. The Toll Bridge Commission saw its chance when the F.E.C. [Florida East Coast Railway] decided to abandon the shattered Key West Extension. The opportunity would have been lost if the federal government, specifically the Public Works Administration, had not supplied the money. The P.W.A. approved a loan of $3,600,000 to finish the highway. In 1936, the Toll Bridge Commission purchased 122 miles of right-of-way "from Florida City to Key West for $640,000 and cancellation of $300,000 in state, city and county taxes."

This is where Leon comes back in. Having divested from Josephus Daniels’/FDR’s “health film” pork-barrel, he began investing in Jewfish Creek real estate, just as FDR’s P.W.A. spending came to fruition:

The Miami News. Sunday, July 30th, 1939. It was a few months after this that the State of Wisconsin went after Chester for Leon’s unpaid taxes totally approx. $25,000. Leon did eventually settle his tax bill.

But all was not well in vacationland. By 1940 Leon and his wife (it’s unclear if she was his first or second spouse) had attracted the wrong kind of attention. A high-profile robbery of the Goetz home in December 1940 made local headlines. The event was not a random one, the thieves watched Leon and his wife’s movements before striking, making off with $200 in cash and jewelry. This is the only mention of Leon living at Bonefish Key “three miles south of the North toll gate of the Overseas Highway”. The robbery was only a slight setback which didn’t stop the pair for long.

According to a Miami Herald article from February 2nd, 1941 Leon Goetz built a “CBS residence" [Concrete Block Structure] at 2490 South West 24th Street in Miami for $6,430. He was probably building this to sell as opposed to live in himself. The property still exists, it is a three bedroom, two bathroom home of 1,857 square feet and is currently priced at around $640,000. (Images from Zillow.)

The House that Leon Built. 2490 S. W. 24th Street, Miami FL. Alternate and interior views below.

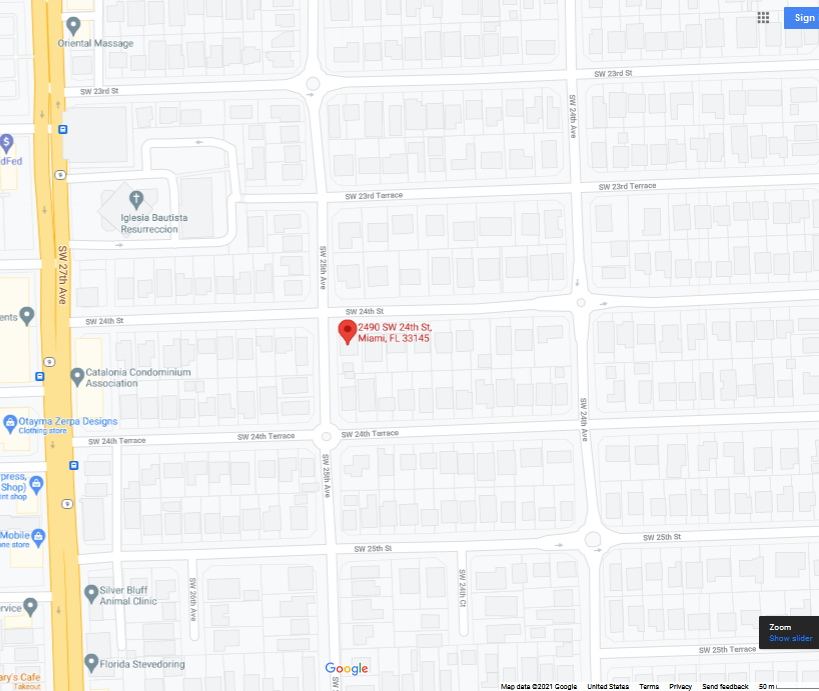

Below is 2490 S.W. 24th Street as marked out on a modern Google map— the densely-packed development of small homes in 1940s Miami is very clear:

By 1944, however, Leon had diversified his real estate endeavors. As an example of his stock-and-trade, here are a pair of properties he advertised for sale on January 18th, 1944:

Miami Herald, January 18th 1944.

Miami Herald, January 18th 1944.

Both of these properties still exist and carry an estimated price of $1.8 million (Riviera/Coral Gables neighborhood) and $980,000 (Coral Way) respectively— they were both built prior to Leon’s ownership. Even though the second is part of “Brickell Estates”, it is not near the new financial center “Brickell”. A number of Leon’s investments took the Brickell name in an effort to reflect the glamor of when the Brickell neighborhood was “Millionaires’ Row” prior to the 1930s.

Leon’s investments clustered in the “Coral Gate” subdivision of the “Coral Way” neighborhood. Today, the vast majority of residents in Coral Way (approx. 70%) are foreign-born and about 40% speak English poorly or not at all . Similar statistics hold for Brickell, the “Manhattan of the South”, though most people hold some sort of degree and the average income is double that of the rest of the city. This area, particularly Brickell, has become a concentration point for money exiting Latin America for a variety of reasons. According to Wikipedia: “The north and east boundaries of Coral Gate are enclosed by walls or street barriers with all vehicles blocked from entering or exiting through these directions.”

Incidentally, Leon’s place of business 1830 S.W. 3rd Ave. is on the extreme West of the Brickell neighborhood— probably in or bordering “The Roads” neighborhood and is now the site of a liquor store.

By June of 1944 Leon and his wife executed a remarkable deal selling Knights Key, part of the city of Marathon and one of the islands of the Overseas Highway. Knights Key was the setting for action movies “True Lies” (1994) and “License to Kill” (1989).

Miami Herald, June 18th 1944.

Leon Goetz’s business kept growing, and over the 12 months of Jan 1944-45 (at least) he actively advertised a number of properties for sale in The Miami Herald:

Miami Herald, December 18th 1944

Miami Herald, December 31st 1944

Miami Herald, January 25th 1945

Miami Herald, January 30th 1945

Although the newspaper record of Leon’s real estate activities ends in 1945, his business was still going strong in 1953 and yielding dividends:

Miami Herald, November 28th 1953.

Mrs. Claudia Rice Goetz was Leon’s third wife and was still with him at the time of his untimely death. Red Road, or West 57th Avenue, is a busy thoroughfare that is now broken up into different segments. Red Road is probably the “highway” from which the car swerved to hit Leon on his lawn, but the plan of the city has changed so much that I cannot locate the home today. Many of the homes in this general area are quite valuable.

Leon did well for himself in Florida— perhaps better than he ever did in Wisconsin or Illinois— but he was not the first member of his family to venture South. Leon actually followed his father, John Conrad Goetz, who moved out of Monroe in 1934. It was only Chester’s family who stayed, and it’s because of them that our town still enjoys the 1931 theater and the Sky-Vu, one of the few remaining drive-in movie theaters in the nation.

The Goetz boys were very close to their father, but I think Leon was particularly close. I found a number of moving things pertaining to the relationship between Leon and his dad in Green County’s civil court records, things that may explain Leon’s early entry into the movie biz and will be the subject of an upcoming post.

* The reason independent exhibitors like the Goetz Brothers were adversaries to the producer/distributor “Majors” was because the Majors always sought to force their customers to buy the bad movies they made as well as the good ones. While Hollywood excels in ‘special effects’, and luscious material attributes like costumes and backgrounds, they’ve always struggled to produce films with good plots. For some reason their executives lack the requisite understanding to consistently produce engaging stories. The “Star System” is a band-aid for this failure, and the persistence of the Star System is a more eloquent expression of the soul of this industry than a thousand Harvey Weinstein exposés.