Janet Jennings: 'Angle' of the Seneca

Janet Jennings is one of Monroe, WI’s most famous women— but she is famous for all the wrong reasons. History knows her as either an army nurse or as a Red Cross Nurse, but she was neither. She was an undercover reporter who utilized contacts inside the Red Cross to get around government restrictions on journalists at the front line of Theodore Roosevelt’s Cuban conflict. In 1898 Jennings pretended to be a nurse in order to get war information.

By exploiting her press-moniker as the “Angel of the Seneca”— bestowed because she did nurse men on this ship for a few days under appalling conditions— Jennings protected Teddy Roosevelt and other high-ranking politicians in McKinley’s cabinet from criticism for their poorly-organized Cuba invasion and the staggering loss of life that resulted. Rather than have Navy Undersecretary Roosevelt, War Secretary Russel Alger, nor the complicit Surgeon General George Miller Sternberg held accountable for war profiteering, Jennings used her well-developed powers of righteous indignation; her newspaper contacts; and her sex to have the Cuba debacle blamed on the captain of another struggling medical ship. Subsequently, Jennings remained silent when Sternberg shifted blame instead to the two young, inexperienced male doctors— military contractors, mind you— under whom Jennings volunteered aboard the Seneca. Ironically these two doctors, Thomas Baird and William Hicks, were as much “Seneca angels” as Jennings ever was.

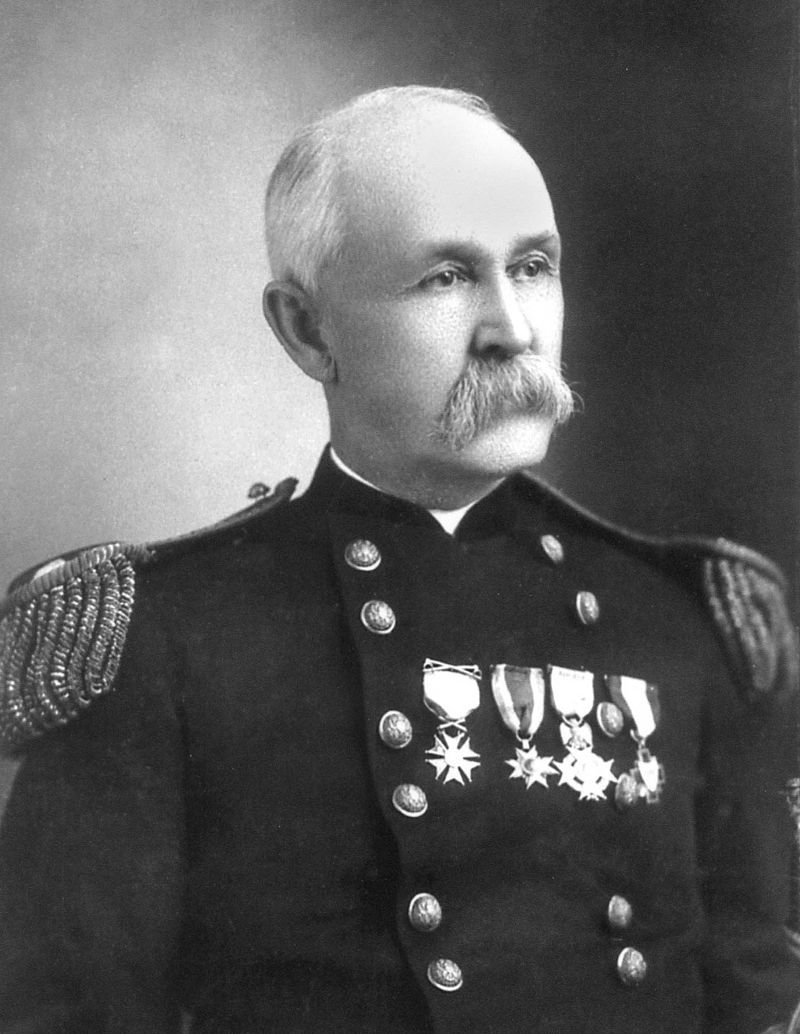

Roosevelt and Sternberg, two architects of the biological disaster known as “The Spanish-American War”.

And if you’re wondering, the answer is YES, Jennings worked for William Wesley Young’s newspaper, the New York World, during this shameful episode. According to the work of historian John Evangelist Walsh, William Wesley’s paper was her most incendiary mouth-piece, though this paper was not available to me. I’ve based my research off her appearances in the New York Sun and the New York Times, which made themselves useful to the same end.

Longtime readers will not be surprised to learn that William Wesley’s paper was behind Jenning’s manipulative exposés. Young got his start in propaganda work alongside his business partner/friend Davis Edward Marshall who was instrumental in Theodore Roosevelt’s reorganization of the Galician prostitution network in NYC— otherwise known as Housing Tenement Reform. Beyond human trafficking for prostitution, the Galician Network specialized in electoral fraud and were good friends of the Roosevelt clan. This had fascinating implications for Monroe’s history, see Leon Goetz in Florida. Naturally, a little digging into Jenning’s background reveals her own connections to Monroe’s sex-trade history.

Nobody knows when Janet Jennings was born, but we do know she was around 24 years old sometime during the US Civil War (1860-65) . Jennings taught in Monroe’s school system prior to her pilgrimage to D.C.; our school system was dominated by the Ludlow clan and their business partners, as well as family members of Monroe’s likely top madame, Almira Humes.

During that war (1860-65) and the reign of the Bonelatta counterfeiting gang (1857-71) which was supported by the Lincoln administration, Jennings made her way to Washington D.C.. A few weeks after arriving in the capital she was given authority over vast numbers of convalescing soldiers, despite having no medical experience and her appointment being contrary to medical regulations at the time:

Jane Jennings was the third of twelve children raised on a farm in rural Wisconsin. She was 16 before she was exposed to formal schooling. Much like Walt Whitman, when one of her brothers was injured in the Civil War, she traveled to Washington DC to do her part in the war. With no formal training as a nurse she volunteered for the Union Army corps of female nurses but was turned down by Dorothea Dix, because at 24 she was too young. Determined, she appealed to Dr. Bliss, head of all the Washington hospitals, and was put to work in one of the tent hospitals in Washington. Within weeks, she was in charge of several tent hospital units.

After the end of the Civil War she stayed in Washington working at the Treasury Department until she had to return home due to poor health. There she turned to journalism writing for Wisconsin newspapers and publishing two books about the Civil War: “Abraham Lincoln, the Greatest American” and “The Blue and the Gray”.

“Dr. Bliss” was Dr. Willard Bliss, a quack doctor from New York state who had been expelled from Washington D.C.’s Medical Society in 1853 for selling a species of snake-oil, “cundurango”, as a cure-all for “cancer, syphilis, scrofula, ulcer...and all other chronic blood diseases”. Bliss was also a homeopathic doctor and like many 19th century protestant religious radicals, he was a proponent of racial integration in D.C.’s medical community. This combination of politics and dogma would put him in good stead with Monroe’s counterfeiting/prostitution/Universalist community.

Despite Bliss’ very dubious medical competency and charlatanry, Lincoln’s administration put him in charge of D.C.’s Armory Square Hospital, from where the doctor cultivated media contacts such as Walt Whitman and later Jennings. Bliss ended up doing jail time in 1863 for corruption and bribery relating to his hospital administration.

Willard Bliss (R) and his brother Zenas circa 1861.

Given Dr. Bliss’s record of malpractice and corruption, it is perhaps less surprising that he’d appoint a bonny young lass from Monroe to such a responsible position in D.C. Whatever Jennings was doing there did nothing to train her as a nurse, and she was still untrained as such in 1898. More insight to what was really going on is provided by the fact that after the war Jennings left Bliss for the Treasury, which was run by Salmon B. Chase, the ultimate political patron of star Bonelatta engraver Thomas Miner. Young Janet was protected by the criminal gang which ran Monroe, WI and the nation’s finances. (A number of Jenning’s sisters would also find positions in D.C.)

Not surprisingly, the Treasury under Chase was marred by sexual impropriety, from Illegal Tender, by David Johnson:

Although the [Secret] Service had fewer detectives than the Postal Inspectors, it quickly established itself as a general policing agency for the federal bureaucracy. This position may have evolved from the combination of a wartime scandal and other problems in the Treasury Department. The scandal occurred when Secretary Chase had decided to hire female clerks, one of whom had promptly become embroiled in accusations of sexual misconduct. With its employees’ moral character at stake, Treasury officials had displayed a persistent though erratic willingness to use Service detectives to check on their workers’ private lives. Beginning in December 1865 the Service became the occasional moral guardian of the Treasury.

Readers may remember that Chase staffed his Secret Service with criminals who would ‘investigate’ gangs that rivaled the Bonelattas and their satellites. With the eventual break-up of the Bonelattas in 1871, the Secret Service delivered the domestic counterfeiting market into the hands of foreign criminal syndicates: Italians and Eastern European Jews— though they showed far more zeal investigating the former. What Jennings was doing at the Treasury Department is obscure, but she seems to have left around the time Chase did (late 1870) and at the beginning of the Grant administration’s anemic Bonelatta prosecutions:

After the Civil War she [Jennings] continued to live in Washington, securing a position in the Treasury Department. It was some years later that, still in Washington, she began her career as a journalist. Though never a “name”, in time she became a much-traveled and well-respected newspaperwoman, contributing to papers in New York, Washington, Boston, and Chicago. Working out of Washington, she grew to know many top government officials, even managing to meet several presidents. Ulysses Grant she knew well, and was among the last to visit him in New York shortly before his death in 1885. [note]

[note] Her acquaintance with Grant is mentioned in her own privately printed book, The Blue and the Grey [Madison, WI, 1910]. It is also said that she knew Abraham Lincoln, but in her own writings on him there is no hint of such and acquaintance.

[From John Evangelist Walsh, “Forgotten Angel”, WI Mag of Hist.]

Readers may like to refresh their memory about President Grant’s life in the rough mining town of Galena, IL and its connection to Almira Humes, of Monroe’s whiskey hotel. Grant’s political base consisted of oligarchs who profited from businesses which catered to miners in the Upper Mississippi Valley. These men followed him to national power in Washington.

The various phenomenon that Jennings took part in while living in D.C. had a huge effect on life in American cities. There are two developments which impacted women particularly: the unprecedented prostitution explosion and mass mobilizations as nurses for the war effort.

D.C. was a locus for pimps and madames who, encouraged by generals such as Joseph Hooker [Union/Lincoln], descended around military encampments en masse. From “Public Women and the Confederacy” by Catherine Clinton:

Hard times could not be the main factor creating the boom in prostitution from 1861 to 1865. Rather it was the mobilization of rival national armies which was the greatest causal factor. And thus the Civil War was the primary cause of the largest increase in the sex trade in the nineteenth century, perhaps the single greatest spurt of growth in the nation’s history. The dramatic leap in the number of American prostitutes [prostitutes working in America?], this exponential expansion of the sex trade was a mounting concern during wartime. Yet civilian moral reformers were forced to delay any preventive or punitive campaigns until a military resolution to the war was concluded.

The result of this “boom” was an explosion in venereal disease, leaving civic authorities— often for the first time— the unenviable task of dealing with a shadow army of sex workers and their exploiters, mostly career criminals with political favor. This is exactly the situation which plagued Central European communities that hosted Hapsburg forces and that corrupted the nascent democratic institutions there— particularly nationalist-leaning institutions. Throngs of young prostitutes— with all the behavioral problems moderns associate with gangs of juvenile delinquents— accosted peaceable citizens and made life in public spaces unsafe. As the southern city of Richmond, VA learned firsthand, these women and their pimps were prone to rioting, too.

At the same time this “boom” was happening in the United States, in Imperial Austria, the heartland of the global sex trade, political allies of the international pimps in Hungary, which supplied most women for the international trade at this time, had entered a new phase of political power with the establishment of the Abgeordnetenhaus. Something like a US Congress, the Abgeordnetenhaus was a power-sharing agreement between Emperor Franz Joseph and his liberal party oligarchs, many of whom had betrayed Central European nationalist causes in exchange for the privilege of running brothels in Budapest, Trieste, Prague and other places. The early 1860s marked Franz Joseph’s going ‘all in’ with sex traffickers. [Parallel: Lincoln’s quashing Grant’s efforts against Jewish smuggling networks during the Civil War.]

I cannot yet say where all the prostitutes who flooded D.C. came from, but typically for this period they would be mostly indigenous women, complimented by a substantial foreign corps (maybe even 50%— foreigners comprised 60% in NYC). Even among U.S.-born prostitutes, the order of the day was to remove women from places where they had social support structures: both Northern and Southern women were ‘relocated’/trafficked for the sex trade. This happened on a massive scale. In D.C. and just over the Potomac in Virginia, the number of known prostitutes increased 1400%— from about 550 to 7500 women. The nature—particularly the criminal nature— of our nation’s capital had been irreparably altered.

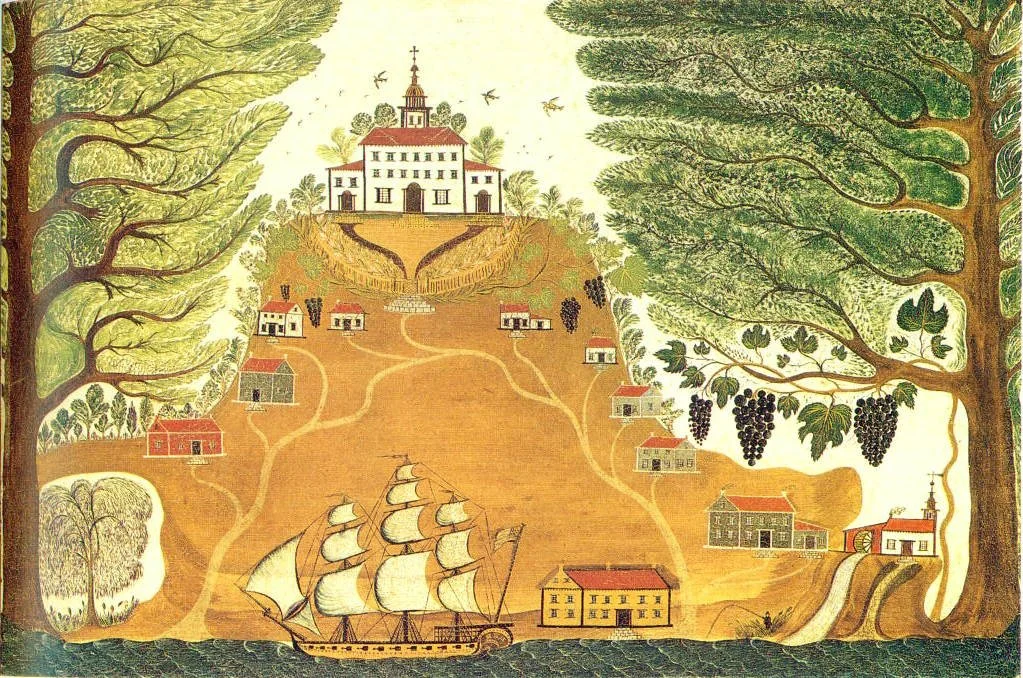

“Hooker’s Division”, the name of Washington D.C.’s red light district, existed until 1914. Note how these houses looked to the [Federal] “Government”, but not the city, for patronage. The FDR administration subsequently developed this area into offices to house its massively expanded federal government institutions, staffed with its partisans. The FBI building is also in this immediate area. Library of Congress.

Notice all of the listed bawdy-house operators are women. Typically, these madames would own the bordellos on paper but were actually in the ‘employ’ of higher-ranking pimps who may control one or more brothels. The pimps would move around between their properties to obscure their role in their enterprise; in the event of police action the resident madame would take the fall.

Nurses were another group of women who followed soldiers. I chose my words carefully there, because the age-related policies of women like Dorothea Dix had a double motivation. Dix didn’t want to recruit young nurses because the emotional development of these girls was likely not up to the task of nursing. An unmarried women may never have seen a naked man before; she probably always had the protection of her family and had little experience dealing with gore or unwanted attention. Many of the men in care were not of sound mind. It is to the credit of (real) nurses like Dix that she chose to exclude young women from military nursing.

The second motivation mirrors the explosion in organized prostitution. Access to troops was a valuable commodity for sex merchants and certain roles, such as laundry-women, became a common “in” for prostitutes. As unseemly as it is, pimps would have viewed access to the hospitals as another venue for doing business. This business model would have both angered those favored pimps without hospital access, and turned the military hospitals into petri dishes for venereal disease. As things stood, bordello owners did their best to cater to the wounded and sick [Clinton, p. 21]:

Confederate leaders witnessed with alarm the growing numbers of men struck down by sexually transmitted diseases… And even in the Richmond hospitals, disabled soldiers weren’t safe, as in 1862 one enterprising madam opened a brothel directly across the street from a hospital run by the YMCA. Females hawking their wares appeared in windows in various states of undress to try to entice patients from their beds. The manager of the hospital remonstrated that this activity was interfering with the soldiers’ speedy recovery.

By excluding marketable women from nursing corps, Dix protected both soldier’s health and the war effort. Jennings did not feel bound by such considerations. (I will point out that Bliss’s other creature, Walt Whitman, came from a family where women practiced prostitution. See: Clinton, p. 12.)

US military authorities eventually instituted the same regulation and registration policies that Franz Joseph adopted in his empire, with the same result: venereal disease doctors ended up deciding which prostitutes could work in their territory. Modern historians identify this as the ‘medicalization’ of prostitution and by the 1880s it was Galician VD doctors who by enlarge controlled the international trade. The US military abandoned their registration system as futile by 1865— it would persist for decades in Central Europe because of its patronage from Franz Joseph and other leaders.

Before entering into Jenning’s career as a journalist, I’d like to point out that she left Washington D.C. “several years” after the war because of “poor health”. Jenning’s critics (medical men) described her as “hysterical” and there may have been an element of truth to this claim— though modern labels would likely be “bipolar-” or “manic disorder”. On returning to Monroe, Jennings lived alone and developed a reputation for eccentricity and cantankerousness. She never married. It was thirty years after her death before the town organized a gravestone for her— no one in her family stood up to pay for one before then.

Janet Jenning’s home in Monroe, WI. It’s about five blocks north of the Square where Leon Goetz would eventually build his theater. Many of Monroe’s wealthy English-derived families owned properties in this general area, including the Ludlows and the Binghams. North of the Square was advantageously situated with respect to the Madison WI-Freeport IL railroad (the one coming up via Orangeville IL).

War and political upheaval can be particularly hard on the mentally unbalanced, who are at times exploited by immoral actors for political ends. This is nothing new. Wanton violence and even cannibalism characterized Revolutionary Paris: theses acts were perpetrated by unhinged crowds both hungry and drunk on half-baked notions of “equality”, “liberty” or “justice”. Over the border in Hesse, the government of Johan Wolfgang von Goethe noticed the same deterioration in mental health among its own people [Das Goethe-Tabu, W. Daniel Wilson]:

The next summer Schnauß wrote to Carl August: “The number of insane madmen is increasing more and more. There is no more space in the orphanages nor workhouses. The school for soldiers’ children and the free school must be closed. Suicide appears to be becoming epidemic.” The reasons for such a complicated phenomenon can of course no longer be ascertained correctly; wars are often accompanied by such psychologically borderline phenomena. (It is possible, but not provable, that political dissidents were also understood as "lunatic".)

Even in our own time there are people who exploit the mentally unbalanced in pursuit of political power. Therefore, I ask readers to evaluate the following sad episode in Jenning’s life in light of the fact that she may not have been entirely competent.

In a move strikingly similar to her flaunting nursing regulations during the Civil War, Janet Jennings misrepresented herself as a Red Cross nurse to get intelligence on the 1898 Cuban conflict. Her actions corresponded with Theodore Roosevelt’s media offensive [May -December 1898] which was designed to portray him as a virile military leader and presidential material— something for which Republican Party leaders doubted his suitability. From the Library of Congress:

Roosevelt and the commander of the unit Colonel Leonard Wood trained and supplied the men so well at their camp in San Antonio, Texas, that the Rough Riders were allowed into the action, unlike many other volunteer companies. They went to Tampa at the end of May and sailed for Santiago de Cuba on June 13. There they joined the Fifth Corps, another highly trained, well supplied, and enthusiastic group consisting of excellent soldiers from the regular army and volunteers.

The Rough Riders saw battle at Las Guásimas when General Samuel B. M. Young was ordered to attack at this village, three miles north of Siboney on the way to Santiago. Although it was not important to the outcome of the war, news of the action quickly made the papers. They also made headlines for their role in the Battle of San Juan Hill, which became the stuff of legend thanks to Roosevelt's writing ability and reenactments filmed long after.

William Wesley Young’s friend, business partner, and fellow British intelligence agent Davis Edward Marshall cut his teeth shilling for Teddy Roosevelt on his “Rough Riders” expedition, as did the son of the Philadelphia Public Ledger’s editor, Richard Harding Davis, who wrote for the New York Sun— one of my principle newspaper sources for Jenning’s Seneca media offensive. Historian John Evangelist Walsh explains her mission:

Janet Jennings was neither an army nurse nor a Red Cross nurse. She was an experienced newspaper reporter, one of the horde of correspondents that descended on Cuba with the American forces in the summer of 1898. She went there intending to report the conflict, not to care for its casualties. It was the deadly crush of circumstance, during the notoriously confused campaign against the Spanish stronghold of Santiago, that thrust her suddenly into the role of nurse, a short-lived role that rapidly propelled her into the national spotlight as well…

Properly, the story begins on the deck of a small steamer, the “State of Texas”, as it steers south from Key West late in June of 1898. A Red Cross ship, the Texas was under the personal direction of Clara Barton, the organization’s founder. Bound for Cuba, it was carrying food and medicines for America’s allies in the fight, the hard-pressed Cuban insurrectionists, as well as hapless hordes of displaced persons… She [Janet Jennings] was there, not as a nurse, but to get round the government ban on female reporters working in the war zone. This strict prohibition barred them from even traveling to Cuba.

A long-time supporter of the Red Cross, she had prevailed on Clara Barton to list her as an official member of the relief group. (Another woman reporter, Katherine White of the Chicago Record, did the same.) But the arrangement was not entirely a subterfuge. Miss Jennings was mainly interested, no in military matters but in the human side of the conflict, and had agreed to give part of her journalistic effort to filing stories on the work of the Red Cross itself. To that extent, her status as primarily that of a Red Cross reporter, even where women were ordinarily not permitted, was legitimate.

More succinctly: a journalist, Janet Jennings, exploited a supposedly humanitarian vessel which was being used to support combatants with the connivance of the Red Cross founder, to misrepresent herself to the US government so she could gather military information in knowing contradiction to clear prohibitions against doing so.

Prior to this deception, Jennings had already met with Surgeon General Sternberg in Florida, who advised her against sending more Red Cross nurses to Cuba (see Sternberg’s reply to Jennings in the Sun, August 27th 1898, reproduced below). Political activist and Russia explorer George Kennan was already snooping around the Cuba front under cover of the Red Cross when Jennings met with Sternberg.

At the time of her Cuban deception, Jennings was writing for the Chicago Times Herald, which was owned by Herman Henry Kohlstaat. Kohlstaat was the son of a Danish army officer and an Englishwoman, both ardent abolitionists who lived in Lincoln’s home state Illinois. Herman Henry made a fortune in Chicago bakeries and was an advisor to William McKinley [Republican], Theodore Roosevelt [Republican], William Howard Taft [Republican], Woodrow Wilson [Democrat, elected with Theodore Roosevelt’s help], and Warren G. Harding [Republican].

Janet Jennings got a good deal more than she bargained for, however. Endemic corruption and inadequate planning for the invasion resulted in her being pressed into actual nursing as she disembarked at Siboney on June 26th, 1898. After about two weeks and despite a severe shortage of staff, Clara Barton sent Jennings away to help get ice from Jamaica (why Jennings was needed for this undertaking is unclear). When Jennings returned alongside the ice, she was immediately allowed to leave again on a makeshift hospital ship called the Seneca which was scheduled to return to NYC with hundreds of wounded men. The Seneca had neither staff, water nor medicines adequate to the voyage. The Relief, a modern hospital vessel, was retained at Siboney to meet an anticipated influx of wounded from intensified fighting inland. (Many of the socially-connected “Rough Riders” would have been among those anticipated.) The Relief had few extra materials with which to outfit the Seneca, but what it could spare was sent over. All medical personnel in Cuba were caught in an impossible situation.

Naturally, the trip to NYC was a nightmare although no soldiers died. This is to be expected, as medical authorities at Siboney had only cleared the strongest convalescents for the trip on the Seneca. Most civilian Seneca passengers— newspapermen, movie men and foreign officers observing the fighting [from Sweden, Russia, Germany, Turkey, Japan]— gave up their cabins to the wounded (two of the foreign officers did not). Of the 40 or so civilians, 15 volunteered to help nurse alongside Jennings. Interestingly, the wife of Sylvester Scovel, a New York World reporter who had an ugly public feud with General William Shafter, the commander at Siboney, was also one of the Seneca passengers. Mrs. Scovel was too sick to nurse.

The military’s Medical Department had a very sour relationship with the Red Cross, which got its information and orders from the State Department under William Rufus Day— a Teddy Roosevelt partisan who helped with the “anti-trust” political maneuvering against American Tobacco (i.e. one of Benjamin B. Hampton’s negotiating partners)— and Day’s successor, John Milton Hay. Hay was a confederate of Abraham Lincoln from the Civil War era and organized the US military’s authority over the Panama Canal in 1903. In short, a cabal familiar to Monroe, WI’s “great and good”.

With its illustrious State Department connections, the Red Cross did not fit comfortably into the chain of command which oversaw the Cuban invasion. Military doctors complained of a dilettante civilian organization which undermined discipline; miraculously inserted themselves into desperate situations; then complained loudly to the press. Indeed had they known more about Jennings, army physicians could also point out the Red Cross’s affinity for political espionage. There was some truth to these criticisms: Red Cross women appeared wherever the press or movie industry personnel sought a war story.

Conversely, newspapers which supported the Red Cross, like the New York Times and the Sun, were eager to use their power to promote Red Cross interests at the expense of those of the Military Department. The names of Red Cross donors were trumpeted across the broadsheets and the elite social connections of Red Cross volunteers were flaunted. Jennings was a useful tool in these proceedings.

Once the “horror ship” reached New York City, newspapers allied with Theodore Roosevelt were quick to stoke the public imagination about conditions on board. The New York World, where William Wesley Young had worked for three years; the New York Journal; The Chicago Tribune; and the Philadelphia Public Ledger carried stories about the “angel” Janet Jennings and the horrendous conditions of her voyage— all of which Jennings alleged were attributable to the military’s Medical Department and the crew of the Relief. The name of “Theodore Roosevelt”, a war-hawk who was Assistant Secretary of the Navy at the time of planning the invasion, was kept out of discussion.

Headline from the New York World, July 25th 1898 as reproduced in Walsh’s “Forgotten Angel”.

Jennings began giving press conferences the same day she was cleared from quarantine in NYC. She was quick to lay the blame on the crew of the Relief as well as medical authorities at Siboney. Jenning’s naive attitude about the Relief’s scope for independent action and the widespread planning problems which plagued the invasion ring untrue for a women of 51 years and participant in two wars. Surgeon General Sternberg was quick to counter Jenning’s claims and express his opinion that the back of a battle front was no place for Red Cross nurses. From the newspaper sources available to me, Jennings never came to the defense of her fellow Seneca medics, Drs. Baird and Hicks, when Sternberg pinned the blame on these medical contractors. Rather, Jennings countered that Sternberg’s attitudes towards the Red Cross were based on misogyny. It was of course against her interests to acknowledge that the Red Cross was being used by pro-Roosevelt political operatives like herself to spy during wartime.

Read Jennings’ and Sternberg’s full statements in the newspaper articles supplied at the end of this post. Right now, I’d like to look at who, exactly, was funding the Red Cross operations that Jennings and her media masters exploited: Henry M. Flagler.

Goetz aficionadoes first met Henry M. Flagler in my post Leon Goetz in Florida. It was Flagler who hoped to capitalize on Teddy Roosevelt’s Cuba invasion by developing the Florida Keys as a gateway to the island, which quickly became a hub of the international sex trade just like Teddy’s power base NYC. In Florida Leon Goetz, after having been driven out of Monroe, WI on the back of a Mann Act indictment (designed to combat trafficking for the sex trade), became a property developer along the transportation artery (the “Florida East Coast Railroad”) that Flagler had financed. Therefore, men like Flagler had good reason to fund intelligence gathering operations around the conquest of Cuba.

Sadly, the American Red Cross has a long history of being exploited by politically-active millionaires who wish to profit form publicly-funded military efforts. In Sternberg’s statement to the New York Times reproduced below, readers will note that one of the Red Cross’s leading lights was explorer George Kennan. Kennan was active in anti-Tsar provocation efforts much along the lines of what Jacob Schiff funded through William Wesley Young and the Humanitarian Cult— read all about W. W.’s outreach to Russian Jewish immigrants in A Boy and the Law.

New York’s wealthiest families invested in the Red Cross undertaking, including the old Van Rensselaers, who would be stabbed in the back when Edison’s film trust was busted by Roosevelt interests. Among the officers were J. Pierpont Morgan, August Belmont and Dr. Felix Adler (though their wives did the front work). Much like Teddy Roosevelt during WWI, American Red Cross interests were chiefly concerned with getting tobacco products to the soldiers. By the time of the Treaty of Versailles, Red Cross meddling in foreign affairs on behalf of New York City financial interests became so acute that Congress held hearings to investigate these banks’ involvement— the bankers had known the treaty conditions before the U.S. government! Red Cross figurehead and J. P Morgan executive Thomas W. Lamont was a key figure in these hearings. Most bankers didn’t respond to Congress’ subpoena to testify.

In summary, Janet Jennings was at the forefront of a tricky political problem that has plagued Monroe, WI and our nation for many decades. While I applaud her for her few days’ heroism tending the wounded aboard the Seneca— I hope all right-thinking people would do nothing less— I cannot applaud her subterfuge in Cuba nor the way she exploited her good deeds later. As I mentioned, she may not have been entirely competent. She is certainly another example of our less-worthy Monroe element ‘making it big’ at the turn of the 19th-20th century. More will follow!

Surgeon General Sternberg’s reply to Jennings’ criticism:

New York’s Sun newspaper, July 27th, 1898. Part 1/2

New York’s Sun, Jul 27th, 1898. Part 2/2

Jenning’s Retort:

The Sun, August 2nd 1898. 1/2

The Sun, August 2nd 1898. 2/2

Military Criticism of the Red Cross (from a pro-Red Cross paper):

The Sun, August 2nd 1898.