The Palmer House Hotel

In my last post on Arabut Ludlow and Bertha Honoré Palmer, I talked about Monroe’s oral history regarding the friendship between Ludlow and Bertha’s husband Potter. Part of that oral history is that Arabut Ludlow was inspired to build his Ludlow Hotel by Potter’s “Palmer House Hotel” in Chicago.

The Ludlow Hotel sat just north of Monroe, WI’s Historic Square, on the same block as Ludlow’s First National Bank and behind the Young family’s grocery store.

A modern map of Monroe, WI with the location of historic buildings/ tenants marked.

The Ludlow Hotel was razed in the 1960s; in its place stand Genthe’s furnishing store and the Monroe Theater Guild. This is what Arabut’s stately Victorian building looked like:

Arabut Ludlow’s hotel in Monroe, WI. Wisconsin Historical Society.

You can see the back of the buildings along the north side of the Historic Square between the hotel and the white residential building on the RHS. (Those windows correspond to the “Busy Bee” floral/gift store today. ) The two story building with the balcony behind the hotel is the United States Hotel, a far older establishment that was originally built by Charles Hart prior to 1864 (likely the 1850s). During the Bonelatta period, this hotel was run by a Prussian-born US Civil War veteran named Louis Schuetze, who was a notably “active and useful member” of the Turner Society (German exercise club/community hall), according to Arabut Ludlow’s 1884 History of Green County. [page 932] Intelligence agencies from German states were particularly active in the US during our Civil War, read more about that here.

As elegant as Ludlow’s Monroe hotel was, the Palmer House in Chicago was something on a different scale altogether. It is still in operation under the Hilton brand.

Palmer House Hotel, photographed between 1900 and 1910. Library of Congress.

Here is a contemporary advertisement for the barber shop in the Palmer House. Silver dollar coins were set in the floor tiles, a feature which garnered as much derision as praise.

“The celebrated Palmer House barber shop at Chicago. Mr. W.S. Eden, proprietor / J. Ottmann Lith. N.Y.” 1887. Library of Congress

Some of this derision came from high places, according to Bertha’s heirs in her 1961 biography “Silhouette in Diamonds”:

But Rudyard Kipling, staying there [Palmer House Hotel] while on his way home from India in 1889, could see no virtue in Chicago and still less in Potter Palmer’s hotel. He thought the city was inhabited by savages, its air was dirty, its water was like that of Hooghly [a river connected to the Ganges in India, i.e. extraordinarily polluted]. He found the Palmer House a “gilded and mirrored rabbit warren” and decided that a Hottentot [South African Cape herdsman/soldiers with a reputation for ostentatious display] would not have been guilty of having silver dollars inlaid in a floor. His brief view of the hotel left him with an impression of a “huge hall of tessellated marble, crammed with people talking about money and spitting about everywhere. Other barbarians charged in and out of this inferno with letters and telegrams in their hands, and yet others shouted at each other.”

I’ll remind readers that in the newspaper age the only bad publicity is no publicity, so Kipling’s attention should be viewed in that light. Here’s the historically sympathetic interior to the Palmer House Hotel, as maintained by by the Hilton company:

A Hilton promotional image of the hotel’s lobby. This is actually the second construction of the hotel, which was begun in 1871. The Great Fire destroyed Potter’s first hotel and he built this one as a wedding present for Bertha Honoré.

According to a number of historians, a certain type of person liked the Palmer House very much. Silhouette in Diamonds:

The guests were a show in themselves. Swaggering gamblers and gold rush millionaires swapped stories at the sixty-foot bar with Wall Street giants, world travelers, showmen and Viennese opera stars…

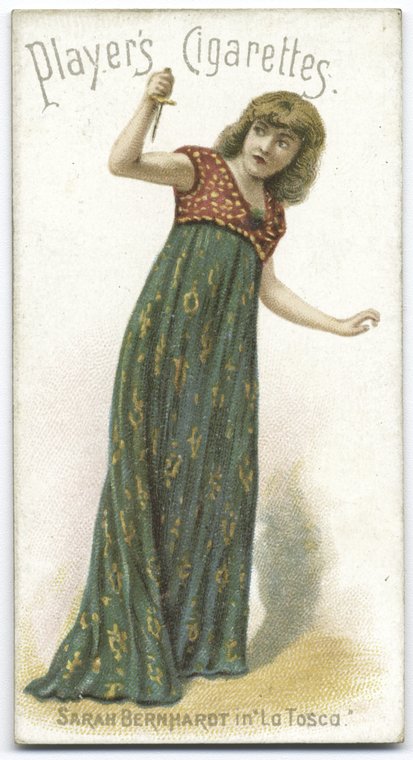

When the Chicago club balked at receiving Sarah Bernhardt on her first visit to the city, Potter Palmer welcomed her as if she were royalty. He gave her a suite of rooms running along one side of the hotel. A “five-glass landau” drove her around town. Her meals were prepared in her own rooms. Her favorite French dishes were on the menu. Mrs. Palmer [Bertha Honoré] refrained from flying openly in the face of convention, and she did not deliberately arrange a reception for her coming, but she believed that all honor was due Sarah Bernhardt, Madam Modjeska and other actresses of great reputation who stayed at the Palmer House.

A portrait of middle-aged Sarah Bernhardt from the UK’s National Portrait Gallery. Sarah’s life ended better than many of her contemporaries.

Helena Modjeska, an actress promoted by Otto Kahn and Theodore Roosevelt in their role as executives of the “Théâtre-Français de New York”. [See p. 114 “Many lives of Otto Kahn” Mary Jane Matz.]

Sarah Bernhardt was a high-class prostitute, as were most famous fin-de-siècle actresses. In an age where glamor was key for recruiting/grooming children for prostitution, these actresses served as informal ambassadresses. That’s why discerning society didn’t want anything to do with them. (Interested in the Galician Gang and child grooming? See my post Cigarettes and the White Slave Trade.) Cigarette smoking was not normal for women at this time, it was closely associated with both male and female members of Galician Network (Eastern European Jewish) organized crime. [See Cigarette Wars, Cassandra Tate.]

The culture of celebrity which hung around these women, rather than accurate depictions of their faces, is what sold cigarettes and their lifestyle to impressionable young people.

Lillie Langtry on a cigarette card.

Lillie Langtry, actress/mistresses of Edward VII, was an 1890s “influencer” who was famous for her many “relationships” with wealthy men and whose public image was underwritten by the bankers of the Marlborough House set, who in turn were good friends of Bertha Palmer.

Actresses fêted by the Palmer House Hotel like Sarah Bernhard, or for that matter Lily Allen, Lillie Langtry or “La Belle Otero”, were the glamorous end of the White Slave Trade, otherwise known as organized international prostitution, which was dominated by the Galician Network out of Austria-Hungary. Traveling musical and theatrical acts were a primary cover for this trafficking— the same type of traveling acts which Chicago showman Dr. Florence Ziegfeld specialized in sourcing en masse. In a similar vein, Viennese opera stars were a commodity favored by early film magnate and Austrian intelligence agent Otto Kahn.

“La Belle Otero” plugging “little white slavers”, a nineteenth century slang term for cigarettes. (!)

Lily Elsie, another high-class call girl/actress, was self-conscious of public perceptions of the rich gifts she accepted from well-positioned men. Her career was made wearing Lady Duff Gordon costumes on stage. In her declining years, LDG costumed Flo Ziegfeld’s Follies girls. Ziegfeld was the son of Bertha Palmer’s musical lackey in Chicago, Dr. Florence Ziegfeld.

The Palmer House Hotel was an extension of Bertha Honoré Palmer’s public image: she was every inch a creation of Chicago’s press magnates as Empress Elisabeth was of those in Vienna. (In fact, Potter Palmer liked to call Bertha “Cissie”, just like the empress’ pet name “Sisi”.) Potter gifted the hotel to Bertha as a wedding present, and they even lived there for a while after their marriage. Potter would sit in his glass office by the hotel door all day and oversee who came and who left. [Silhouette in Diamonds, p 37.] An interesting way for a land developer to pass his time, no?

Just like Empress Sisi promoted bordello culture, the press image of Bertha Palmer was every inch that of Sarah Bernhardt, or Lillie Langtry, too [Silhouette in Diamonds. p 210] :

Bertha used her most expert party touch on this occasion [the private performance of Strauss’ “Salome” for Edward VII in 1908], according to the New York World correspondent, who wrote:

Mrs. Palmer was tireless, standing near the door of the concert room seeing to everything herself. Every guest had a comfortable chair for the concert, and chairs and couches were placed along the corridor, where the gentlemen and the ladies, too, finished their cigarettes while enjoying the music. It is becoming the rule rather than the exception at parties for some of the women to remain with the men, after dinner, to smoke. Six ladies, including Lady Paget, did this at Mrs. Palmer’s party, not going into the concert room until the musical program was half over.

Both Lily Langtry [sic] and Mrs. Patrick Campbell had already made headlines in America by smoking cigarettes in public. The craze was catching on, and Mrs. Palmer’s Salome party gave it fashionable emphasis in London.

I will write more about this “Salome Opera Party” in a future post detailing the connections between Bertha Palmer and Austrian intelligence agent Otto Kahn; I believe this 1908 party’s purpose perfectly reflects that for which the Palmer House Hotel was also used.

Right now, I’ll rudely jar readers out of Edward VII’s floating world and onto the cold pavements of fin de siècle Chicago, IL. The Palmer House Hotel was the ultimate stop for Chicago’s sex-tourism industry until 1910.

Chicago Tribune, July 7, 1901. Chicago’s main vice district, The Levee, enjoyed a bonanza of investment from the beginning of Columbian Exposition planning (1891) to the time of the publication of these images.

The most famous book on the Levee is Lords of the Levee by Lloyd Wendt and Herman Kogan. It chronicles the connections between Chicago’s corrupt Democratic Party politics (the Republicans weren’t much better) and the organized sex trade. Here’s what Wendt and Kogan have to say at the beginning of their book, when they introduce us to the Palmer House Hotel:

A scouring scrub at the Palmer House Hotel following a roaring right in the Levee was considered one of the grandest luxuries the nation afforded, and visiting dignitaries often availed themselves of this delightful, if enervating, experience.

That the Palmer House Hotel’s turkish bath (36 Monroe street, just across State from the main building) would be where men would ‘clean off’ after a night of whoring shouldn’t be surprising given the location of the hotel with respect to the Levee, as well as Potter Palmer and his father-in-law Henry Hamilton Honoré’s role developing State Street after the fire of 1871. I’ll reference the 1913 Rand McNally map of Chicago to give readers a feeling for this district relative to modern Chicago street plans.

1913 Rand McNally map of Chicago with important Dr. Florence Ziegfeld and Bertha Honoré Palmer locations noted. Punters would travel up State Street from the Levee to catch a musical entertainment or a bath. Bertha and her husband patronized Ziegfeld’s soirees at the Central Musical Hall; the talent manager then went on to start the “Trocadero Theater” in time to capitalize on Bertha’s Columbian Exposition. (His son, Flo Ziegfeld Jr., would cut his teeth there with Eugene Sandow.) Dr. Ziegfeld was the musical spokesperson for the Columbian Exposition, even though he wasn’t qualified to be. Dr; Ziegfeld also had extraordinary contacts with the Prussian and Austria militaries— he was something like a spy.

Maroon stars show “Kentucky Colony” interests; Blue stars show those specifically concerned with Dr. Florence Ziegfeld.

The above map shows a very conservative estimation of Chicago’s “red light district”. The Levee was part of a much larger no-go-zone called “Little Cheyenne” in reference to its Wild West-esque lawlessness. Here is Dr. Neil Gale’s/Bryan Lloyd’s estimation of how far the Levee stretched:

The same two historians place the “Cheyenne District” all the way up to Dr. Ziegfeld’s “Trocadero Theater” site on Van Buren Street.

The map below shows the Central Business District of Chicago in 1905. I’m providing it for several reasons:

1) Note the names of the businesses that cluster along State Street, which Potter Palmer and Henry Hamilton Honoré were largely responsible for developing after the 1871 fire using J. P. Morgan money out of anglophile Connecticut.

2) Note the quantity of theaters along State Street. Match the “Folly Theater” to its location on the Gale/Lloyd “Cheyenne District” map.

3) Note the Masonic Temple, as prominently featured during the 1893 Columbian Exposition.

4) Note that the LHS “Federal Building” is the Post Office, and how the U.S. Express [4 blocks North], Adams Express and American Express buildings [1 block NE] cluster near it. Note also the location of the Palmer House Hotel with respect to these “information portals”.

1905 Central Business District map of Chicago, courtesy of the Chicago Public Library.

The Palmer House Hotel sat right on top of the quickest communication lines in the Midwest. The relationship between the US Postal Service and the Express Companies is complicated, but let it suffice to say that agreements were made to protect the interests of the postal monopoly as well as the interests of the railroads on which the express companies were based. The four major express companies were all inter-related; Monroe WI was served by the United States Express Company which was an off-shoot of the New York & Erie R.R.

This “network of four” was built on Livingston money, yes those Livingstons. “Wells Fargo” and “American Express” are the incarnations of their financial/information empire which live on today. Historian Calvet M. Hahn in 1998:

The United States Express Company was third in size and importance among the 19th century express operations. Is also the one about which the least has been written. There were hundreds of express companies operating out of the major cities during the period, but only four were large. The other three were: 1) Adams Express Company (an 1854 consolidation of Adams & Co., Harnden & Co., Thompson & Co., and Kinsley & Co.). At the time of the Civil War, Adams spun off the Southern Express Company to handle its Confederate operations. 2) The American Express Company, a joint-stock company created in 1850 to consolidate Wells & Co. together with the Butterfield, Wasson & Co. and Livingston & Fargo. 3) Wells, Fargo, the smallest of the four, a joint-stock company formed in the spring of 1852 to handle western business. All four still survive today with the United States Express Company being an airfreight forwarding business…

The second United States Express Company was also designed to operate over the New York & Erie R.R. It began with a capital of $500,000 and was headed by a banker, D. N. Barney, who was also the president of Wells, Fargo & Co. A few months later, in the spring of 1855, he also headed the national Express Company, a joint-stock express company that consisted of Pullen, Virgil & Co. and the Northern Express of Johnson & Co. As may be guessed, we have little actual information on the interworkings of the ownerships of the various companies, for little has been revealed in litigation such as was shown in the railroad court cases about the Drew, Vanderbilt, and Fiske interests.

Before becoming a Monroe-Chicago peddler, Arabut Ludlow worked for the US Post Office between Grand Rapids, MI and Livingston County: Arabut ran packages between the city and those wild, border-country lands. (Livingston County is also named after those Livingstons: Edward, brother of the venal Chancellor Robert R. Livingston.) Please see the relationship between Grand Rapids, MI and Freedom, MI where Napoleon Boneparte Latta’s family operated prior to 1857. These little facts add to the intrigue around why Ludlow became acquainted with the Honores so quickly.

The Palmer House Hotel had a lot more to do with the Levee than baths and kompromat. The hotel is where the fabled “Lords of the Levee” cut their teeth and made the contacts necessary to rise in the vice world. For example, Wendt and Kogan [p 17]:

A year later [around 1876] [John “Bathhouse”] Coughlin got a job in the Palmer House baths, reaching the status of head rubber in a few months. Here came the big politicians and businessmen, the congressmen and senators traveling through from Washington, and, on rare occasions, a personage as distinguished as Marshall Field. Coughlin was a favorite with these men; he learned their whims and how to please them.

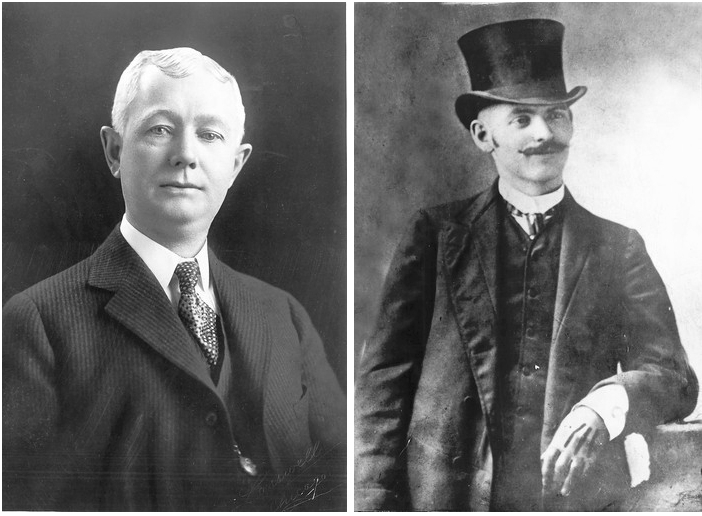

Partners in Crime: Michael “Hinky Dink” Kenna and John “Bathhouse” Coughlin (L to R). This duo rose to take Mike MacDonald’s place strong-arming First Ward residents for Carter Henry Harrison. While both men owe their mob careers to the “Kentucky Colony”, Kenna first got noticed by Joseph Medill, the Chicago Tribune editor, who had a complicated relationship with Carter Harrison. The Chicago Tribune and the Inter Ocean newspapers were both Republican, but somehow still reliable cheerleaders for the staunchly Democrat Bertha Palmer. Thanks to Chicagology for these portraits.

[Examine the Gale/Lloyd map of the “Cheyenne District” and you’ll see two of Kenna’s establishments.]

After a short time at the Palmer House Turkish Baths, Coughlin was set up with his own chain of bath houses around the “First Ward”, the voting district which encompassed the Levee. Coughlin’s break came with Carter Harrison’s bid to be mayor of Chicago for Bertha’s Columbian Exposition. Republicans and Democrats both despised Carter Harrison and Harrison needed men like Coughlin to round up immigrants and factory workers to vote for him, violently round them up, if necessary. Harrison’s old strong-man, Mike McDonald, had become unreliable and the young Palmer House rubber was willing to slide into “Levee Lordship”.

This is not an image from the Palmer House baths— funnily I couldn’t find one— but this is a high-class Victorian “Turkish Bath” which is representative of what one would have found at Bertha’s place. Thank you, VictorianWeb.org.

Another Palmer House election crook was Joseph “Chesterfield Joe” Mackin, who Kogan and Wendt describe as “the First Ward’s dapper Democratic boss, who lived at the Palmer House”. Mackin was a saloonkeeper and election-rigger who eventually got caught stealing ballot boxes and replacing the votes inside them. Mackin was “secretary of the Cook County [Chicago] Democratic central committee” at the time of his exposure [1884], during “Kentucky Colony” politician Carter Harrison’s first stint as mayor [1879-87].

Joseph Chesterfield Mackin was a Pennsylvanian who wound up in Chicago via the Civil War. He ran a saloon on Dearborn Street.

It was Mackin who noticed Coughlin at the Palmer House and had him appointed “Democratic captin of the precinct in which his newest bathhouse was situated.” [Wendt, Kogan p. 19]

Another Palmer House Turkish Bath graduate was Freddie Train, a brothel owner in the Levee. You can see Train’s place on Washburn Ave between Cullerton and 21st street on the map below. (Thank you, Chicagology.)

The red arrow points to a very important brothel, the Everleigh Club, the leading Levee establishment. Freddie Train’s place is on Wabash, at the edge of this conservative depiction of the extent of the Levee.

Freddie Train was a stalwart supporter of Coughlin’s career with the vote-harvesting outfit of Chicago’s “Democratic Party”, which was in fact controlled by the “Kentucky Colony”. It was Coughlin’s rapport with the First Ward saloon-keepers which enabled him and Kenna to deliver votes for Carter Harrison. The way this system worked was simple: saloon-keepers provided alcohol, protection money, and a safe base of operations for “ward heelers”, men who would round up immigrants and blue collar workers to vote for their ultimate paymaster, Harrison, representative of the Kentucky Colony. From The Gambler King of Clark Street by Richard C Lindburg:

Endorsed and supported by the powerful liquor lobby and ethnic fraternal societies organized to defend the saloon trade against Prohibition and blue laws, McDonald’s “ward heelers” were deployed across the city to organize the voters and seize control of the courts, the office of city hall, the bail bondsmen, the police and fire departments, the Cook County Hospital, the sheriff, and wherever else opportunity lurked to plunder the city treasury and acquire “boodle.”

A very colorful interview with one of these “ward heelers”, one “Farmer Jones”, who worked the “ninety first precinct of the hundredth ward”, is related by W. T. Stead in his If Christ Came to Chicago. “Farmer Jones’s” line of business was rounding up Italians to vote Democrat. To accomplish this he exploited a child. Farmer Jones would send in a little Italian girl, about eight years old, to canvass under the nose of the mafioso, otherwise “he could never have done anything” [p. 45]:

“Well,” said he [Farmer Jones], as he lit another cigarette, “two years ago I noticed that a friend of mine who lives down the block had a bright little girl who was beginning to go to the public school. He was an Italian, and a very fine man, although he could not speak much English. I kept my eye on that little girl, and whenever I went to see her father I always took her a pound of candies, or a toy tortoise, or a snake, or anything of that kind, even if to do so I had to borrow a quarter. So I quite got hold of the little girl; she thinks I am her best friend in the world, and she will go anywhere with me, and do anything I want. When the elections come round I just go to her with a bag of candies, and we go canvassing together. She can speak both Italian and English; so she goes with me and translates anything I have got to say. I have got great hold over the Italians here, and it is all through that little girl.”

Grooming can take a lot of forms, and it isn’t necessarily done with an eye towards sexual abuse. Once an adult learns to see children as an exploitable resource, the same tricks can be used to a variety of ends. After this story above, “Farmer Jones” goes on to relate how the little girl came between him a knife blade to the head, when he tried to sell Italian votes out from under an Italian mafioso who was pitching the same wares to the same colony.

Because of support from First Ward saloonkeepers, Hinky Dink and Bathhouse were appointed First Ward aldermen, which allowed them to dictate which vice dens could operate and which would be closed by police. Saloon-keepers and their (often alcoholic) “ward heelers” then delivered the votes which kept the Kentucky Colony, Kenna and Coughlin’s protectors, in power. Freddie Train and his whorehouse were one influential cog in this “machine”.

Pop music fans may be interested to know that Freddie Train’s place provided “talent” for the “American Invasion” of British music in the 1910s: jazz musicians/comedians Elven and Freddie Hedges got their start singing for punters there. This got the brothers, along with third wheel Jesse Jacobson, London contacts by way of San Fransisco (think “David Belasco”) and they eventually ended up recording for Columbia Records in England. The background of these recording companies is riddled with organized crime and quite often intelligence connections.

Bertha and Potter Palmer were equal opportunity employers. Chicago’s “first black vice lord” was John “Mushmouth” Johnson, who “after working as a waiter at the Palmer House, opened his own saloon and gambling house on State Street in the heart of Whisky Row.” [Sin in the Second City, Karen Abbott. p. 92] More from Ms. Abbott:

Calling himself “the Negro Gambling King of Chicago”, Mushmouth Johnson cultivated the usual arrangement with Bathhouse John and Hinky Kink, delivering votes and protection payments in exchange for legal immunity and the title “Negro political boss” in their First Ward.

The Black population of Chicago exploded at the turn of the 19th century, so shepherding them to vote for the Kentucky Colony’s “Democratic Machine” was important. (And yes, every Kentucky Colony family had owned slaves back home.) The irony of history.

John “Mushmouth” Johnson.

As the 1900s rolled around, Palmer House graduate George Little became a money-collector for Hinky Kink and Bathhouse. Little worked in the stables at the Palmer House Hotel and by 1909 was named the “Levee czar” according to Abbott [p. 180]. Besides shaking down bordellos, Little was a boxing promoter. One of his “talents” was Jack Johnston, a Black boxer who liked White women and who would have his own slave-trading troubles. It was the trial of Jack Johnston for violating the Mann Act which exploded Chicago’s prostitution problem into local Midwestern newspapers circa 1912/13. Boxing’s synergy with prostitution stems from at least the 1830s and Central/Eastern European Jewish involvement in London’s crime scene. This synergy would continue well into the 20th century.

George Little is probably the man leaning in toward Johnson on your (the viewer’s) RHS.

If you wanted success in Chicago’s vice-world before 1910, you needed to curry favor through Kentucky Colony networks at the Palmer House Hotel. In keeping with Bertha’s aesthetics, Hinky-Dink Kenna and Bathhouse Coughlin found their own ‘hoity-toity’ way of shaking down the crooks they protected as aldermen: Chicago’s First Ward Ball.

The First Ward Ball was inspired by German-culture bordellos in Little Cheyenne: specifically the annual party for bordello pianist “Lame Jimmy” held at Freiberg’s Hall, a bierstube and “waltz palace” in the Levee on East 22nd Street. When Little Cheyenne vice lords were criticized for their debauchery, they repeatedly fell back on the cultural example set by the peasantry and elite of German Europe. A favorite defense was invoking continental liberalism: “Could a broad-minded city like Chicago afford to be prudish when in Berlin Olga Desmond had danced in the nude before the Society for the Propagation of Beauty, with the approval of Kaiser Wilhlem?” [Wendt, Kogan p 269].

The German connection wasn’t an accident. Men like Bathhouse Coughlin knew ‘there was no honor among thieves’ and that they couldn’t depend on the “Kentucky Colony” when their own cards were down. Coughlin himself diversified his patronage through German intelligence/organized crime networks, particularly that of the Brentano family and their newspaper the Illinois Staats-Zeitung. The Brentanos had been involved in Continental political provocation and espionage actions since the late 1700 and Darmstadt’s legendary intelligence chief Johann Heinrich Merck. The workings of German Intelligence in the American Midwest are a fascinating topic that has yet to find its champion. Politically, the German/Kentucky divide found expression in the Free Silver (William Jennings Bryant) vs. Gold Standard (Palmer House Hotel) conflict inside the Democratic Party, among other places. At this time, the British had a functional monopoly on gold mining via the London Rothschild interests, which motivated their support of gold-backed currencies.

True to its “sans souci” origins, the First Ward Ball was an paraphiliac’s orgy of drunk hookers, gigolos and transvestites— all wares for sale on display for whomever could afford an expensive ticket. Waiters even paid $5 for the honor of working the event. All proceeds then went into Hinky Dink and Bathhouse’s campaign war-chest. According to St. Sukie de la Croix, author of Chicago Whispers, Hinky and The Bath would rake in US$70,000 over the night from thousands of violent and dissipated revelers. (That seems an awful lot, but beyond doubt the orgies were profitable.)

The First Ward Ball continued annually— around Christmastime— from 1896-1908. Bathhouse John Coughlin used the chance to dress every bit as extravagantly as Bertha Palmer [Wendt, Kogan p 156]:

His [Bathhouse John Coughlin’s] tail coat was a crisp billiard-cloth green, his vest a delicate mauve. His trousers were lavender, as was his glowing cravat, and his kid gloves a pale pink. His pumps shone a gleaming yellow, and perched on his glistening pompadour was a silken top hat that sparkled like the plate-glass windows of Marshall Field’s department store.

This is how Wendt and Kogan described the affair in 1907, p 268:

At that ball, [Arthur Burrage] Farwell indignantly noted, some 20,000 guests had slopped up 10,000 quarts of champagne and 30,000 quarts of beer. Riotous drunks had stripped off the costumes of unattended young women, maudlin inebriates collapsed in the aisles, a madam named French Annie had stabbed her boy friend with a hat pin, several toughs suffered broken jaws when they tried to rush a filthy “circus act” in the Coliseum annex, and a thirty-five-foot bar was smashed into bits in one of a hundred free-for-all fights. All but two of the alderman— and those two were ill at home— had attended, and the profits for Bathhouse John and Hinky Dink had been over $20,000.

As the above quotation suggests, not all attendees were prostitutes or under the thumb of a madame or pimp. Oscar-Wilde-type libertines, rich men who didn’t care about their reputations, inveterate thrill-seekers, gangsters and washed-up gamblers also clawed their way in, all clamoring to drink champagne out of hookers’ shoes in the example set by Bertha’s son and Prince Henry of Prussia. [Silhouette in Diamonds, p 145.] This bizarre ‘champagne slipper’ event took place at the Levee’s premiere whorehouse, the Everleigh Club, in March 1902. The bordello’s madam Minna Everleigh had ordered the reenactment of a Greek myth— the cannibalistic death of Zeus’s son Dionysis-Zagreus— as entertainment for the visiting Prince Henry and his entourage. For students of the hermetic occult, the whole affair merits some explanation [Abbott, p 75-77]:

The members of his [Prince Henry’s] entourage wore sweeping capes and frowns that stretched to their necks. Expressions improved markedly once Minna [Everleigh, Levee top madame] greeted her boys and escorted them to the Pullman Buffet [Pullman Room at the Everleigh, named after George Mortimer Pullman] for dinner.

At 1:30 a.m., Minna came to round everyone up, telling the girls the show was about to start— touch up their makeup one last time and don’t forget that they weren’t to wear shoes. The harlots yanked pins from their hair and shook it out, slicing strands with their fingers, the messier the better. They rushed down the spiral staircase and into the parlor, where they found Prince Henry and his entourage at a long table. The girls whooped and swirled in circles, kicking, backs arching like drawn bows. The decisive clang of cymbals punctuated every move. One girl thrashed her way across the room, heading directly for Prince Henry, and just as she reached him she leapt, turned a half circle in midair, and landed on his lap, latching on to his neck. The others followed suit and soon every man at the table was grappling with an Everleigh butterfly.

Minna dimmed the lights, the signal for the second act of the show. In rehearsals she’d used real torches but found that they’d “smoked up the room”, so she’d decided to improvise during the real event.

A servant wheeled a bull made entirely of cloth into the room. The girls raced toward the structure, punching its head and biting its hide, spitting white flurries of cotton. Minna watched, nodding with approval. It was perfect, she thought. This was exactly how the infant Dionysus-Zagreus had been killed. For sound effects, a male butler bellowed each time a mouth clamped down on the bull. Then Minna pointed a finger, and servants fetched platters piled with uncooked sirloin. For ten minutes, the harlots tore into the raw strips, ripping the meat with feral bites, their faces stained with pink slashes of animal blood. The Germans loved it.

When the platters were empty, Minna threw on the lights. She would now take their visitors for a grand tour of the Club. The harlots trooped back upstairs, changed from their fawnskins into evening gowns, pinned up their hair, wiped the blood from their cheeks. A few girls brought dignitaries to their boudoirs, eager to display other talents besides play acting Greek mythology, and hurried downstairs to join the champagne toast when their guests were satisfied.

Minna instructed everyone to raise their glasses, toasting the kaiser in absentia and the prince in the flesh (although the kaiser, after learning of his brother’s visit to the Club, cast a mild insult by asking the vintage of the wine served). She was delighted when the prince returned the favor, comparing Chicago with Berlin, pointing out the American city’s ever growing German population. He called his new friends, Minna and Ada Everleigh, “frauleins”. Ada, who never drank beer, showed her respect by gulping down a tall mug of pilsner.

Minna then ordered the table cleared. She had one more surprise.

Two butlers helped Vidette, the best dancer among the Everleigh butterflies, up to the mahogany surface. The orchestra struck up “The Blue Danube,” and the harlot kicked again and again, her feet flying higher each time, legs meeting and parting like a pair of scissors possessed. In the middle of her routine, one high-heeled slipper launched from her foot, sailed across the room, and collided with a glass of champagne. Some of the liquid spilled into the shoe, and a nearby man named Adolph scooped it up."

Following Adolph’s lead, rich libertines from New York to Moscow continued this rather gross behavior, which no doubt ruined the shoe and got its owner even further in debt to her “Minna Everleigh”. Grooming doesn’t just happen to children, readers, and the above is an example of “hermetic grooming” if I ever read one. Increasing the power of one’s will by influencing others to share that will. The myth of the death of Zagreus is the murder of Zeus’ heir; this ritual should be interpreted as a working against the continuation of the Kaiser’s line: a very ‘Sisi-esque’ undertaking.

Karen Abbott’s unfortunate anti-German bigotry led her to ignore the fact that at the time of this blood-magic-ritual Minna Everleigh was under the thumb of her landlord, an English pimp named Christopher Columbus Crabb who was probably also a serial killer in the manner of H. H. Holmes.

The Day Book, April 5, 1913

For vice to be tolerated, it must be invisible. Coughlin’s Bertha-esque display of whore-house luxury became a political liability for the Kentucky Colony. As a weather-vane, we need look no further than their one-time friend at the Chicago Tribune, Joseph Medill (Hinky’s first sponsor and bestower of the “Hinky Dink” nickname), who became willing to publicize his former confederates’ shenanigans. One smells the stink of Carter Harrison “dining alone”.

The end of the Levee came in late 1909, with the passage of the Mann Act and the bevy of federal investigative agents outside Kentucky Colony control. Within a few months Bertha Palmer, Edwardian society queen and champion of ostentatious display, would run to Sarasota, Florida— where the streets had no drains. The irony of this is not lost on her biographer Frank A. Cassell, who notes in his Suncoast Empire p. 26:

Bertha Palmer could easily have lived out her remaining days in her accustomed ease and luxury. And, indeed, at least for a while, that was perfectly satisfactory to her. However, in 1910 this famous, well-connected, cosmopolitan lady changed her life’s direction and ventured south to the land of mosquitoes, alligators, thick jungle and rough society.

Necessity is the mother of invention.