Glass Blocks

When I began researching the Goetz Theater in Monroe, WI, it was my intention to look into the architecture of the 1931 building. Why? While visiting the Goetz and waiting for the 2019 “Joker” with Joaquin Phoenix to begin, my eyes wandered to the walls above, which were decorated with plasterwork featuring a hand-bell motif.

The mysterious bell motif along the wall visually leads to the screen. Courtesy GoetzSkyVu.com.

Close up of the bell motif. Courtesy GoetzSkyVu.com.

I wanted to find out why the Goetzes had chosen hand-bells, as they didn’t seem to fit in with the ethos of the rest of the building. A few days later, I went to the archives of our local historical society (located in the old Universalist church) but drew a blank— nothing has been preserved explaining the architecture of this remarkable building. Duke Goetz, the grandson of Chester Goetz, who now runs the theater has told me no records from that time were preserved by his family.

The exterior of the 1931 Goetz Theater in Monroe, WI.

I did, however, find out something about the “Goetz Jr”, a theater that Chester Goetz opened in 1936 to cater to the kid crowd. There was a time when young children could go out by themselves for a few hours and watch a movie alone— and parents could reasonably expect them to be safe. This wasn’t just the case in small towns like Monroe, but larger communities as well and as recently as during my grandparents’ lifetimes.

I cannot speak to the exact line-up for the Goetz Jr., but it wasn’t uncommon on Saturday afternoons for theaters to show multiple movies and shorts as a children’s program— an entire package— for about 15 cents. I’m sure many parents appreciated the service that Chester provided.

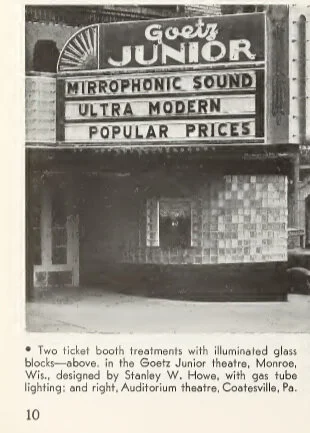

Goetz Jr. Image courtesy of GoetzSkyVu.com

Chester’s gift to the community via the Goetz Jr. went far beyond babysitting. When Chester opened the Goetz Jr, he chose an architectural design that used a modern building material in a remarkable way. The design of the Goetz Jr. facade and ticket office attracted the attention of The Motion Picture Herald in 1937, which featured the Goetz Jr. for its innovative use of illuminated glass blocks.

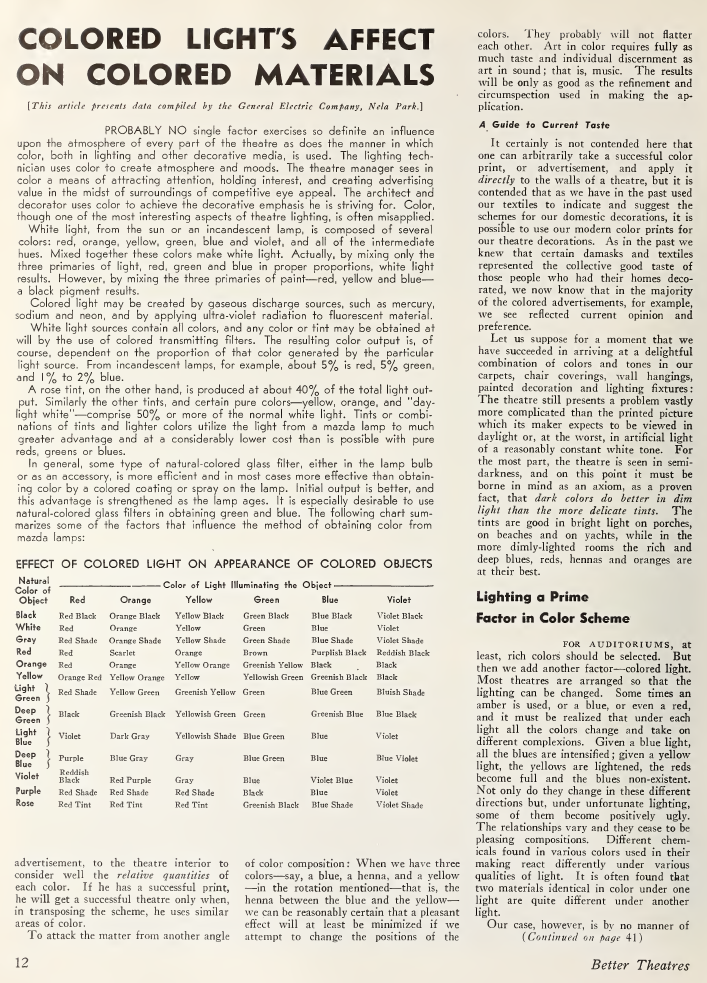

Glass blocks! See the images and accompanying write-up from MPH below, which offers a 1930s perspective on the psychology of color and light using data compiled by the General Electric Company.

Motion Picture Herald, December 11th 1937. 1/5

Motion Picture Herald, December 11th 1937. 2/5

Motion Picture Herald, December 11th 1937. 3/5

Motion Picture Herald, December 11th 1937. 4/5

Motion Picture Herald, December 11th 1937. 5/5

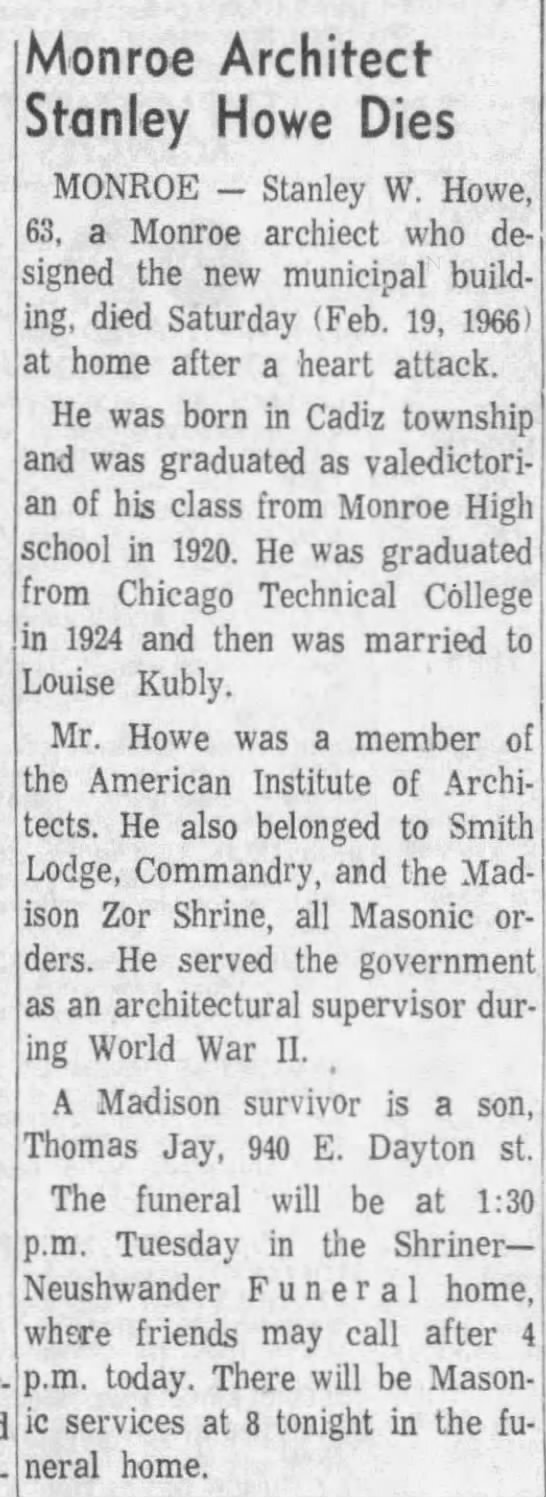

The architect who designed Chester’s Goetz Jr. facade was Stanley Willis Howe, who ran his own architectural firm here in Monroe. I did find an obituary for Howe, who studied architecture in the 1920s. This was the exciting period which inspired “Ayn Rand”, born Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum, to write her books glorifying architecture as an expression of individual will, see below :

Wisconsin State Journal, Madison, Wisconsin. 21st February, 1966, Page 19

It turns out that Howe was the lead architect on another Monroe landmark, Turner Hall, which I’ll talk more about shortly:

American Institute of Architects 1956 Member biography for Stanley Willis Howe, who worked on St. Claire Hospital as well as the 1937 Turner Hall.

I love 1930s architecture. My home, which is located a few blocks from both the Goetz Theater and the site of the Goetz Jr, was also built in the Thirties. Unfortunately the Goetz Jr. was razed in the 1950s to make way for an electronics store which burnt down prior to my memory. There’s just an empty gravel lot there now, though for a time our local horticultural society, the Green County Master Gardeners, made it into a public raised-bed garden.

What I can see from surviving photographs makes me appreciate how Chester chose to use glass blocks, and I think that a lot of other people around town appreciated it too because when Turner Hall, the Swiss community center and tavern, burned down in 1937 it was rebuilt and glass blocks were incorporated in the design. [Correction: A Turner Hall historian has informed me that the bowling alley where the glass blocks were used was constructed in the 1950s. Thank you!]

Outside of Turner Hall on 17th Avenue, which is a block away from the 1931 Goetz and very near what I believe to be the site of Edith May Leuenberger’s grandfather Gottlieb’s brewing factory. The Chalet-roofed building behind the “Ratskeller” sign is across the street from the 1881 Schlitz building where Edith May’s uncle ran his saloon.

Glass blocks incorporated into the architecture of the re-built Turner Hall.

Glass blocks were also used in my favorite industrial building, which must have been constructed in the 1930s. This building abuts the old railway track (which was converted into a scenic walk, the “Badger State Trail”) and faces one of the old railway stations, which was updated at some point with glass blocks.

Old factory structure, circa 1930, alongside the rail tracks in Monroe, Wisconsin.

Close up of the block work on the building above. These windows are on the opposite side of the building from where a dock is located parallel to the tracks. These windows are tough, but would probably not have withstood train debris.

An old railway building next to the industrial building pictured above was also updated with glass blocks. Both of these buildings lie just south of where the Young family fruit farm was located, which supplied fruit to William Wesley Young’s father’s grocery store. The Young store was located in the building that now houses Elite Tae Kwon Do. Young Sr. may have wished he stuck to local fruit after having been bit by a tarantula that hitch-hiked on a bunch of bananas. This incident gave both him and the spider lasting fame.

Large picture windows were a feature of 1930s architecture: new materials allowed architects to bring in fabulous amounts of light, sometimes through just a single pane of glass. Local craftsmen incorporated huge glass block windows into their warehouses and work buildings, for instance Gottlieb Brandli’s cabinetry building below…

Glass block window detailing balances the door to the Brandli’s Cabinetry workshop.

Massive picture windows on the side of Gottleib Brandli’s workshop.

The Brandli workshop sits directly behind the New Holland dealership and service garage which my great grandfather built. Naturally, Grandpa Ernst incorporated swaths of glass blocks, which no doubt saved on lighting costs during the day.

The Studer garage building and dealership, which is now owned by Hennessey Implement.

Glass block picture windows bring light into the garage area of the building…

… from all three sides. Great grandpa didn’t stint on the glass blocks.

The Studer building was also famous for this mural which decorated the interior show room/customer service area. It was painted in 1948 by Herman Wall, you can read about it here.

As time went on, the stately Victorian houses which wealthy tradesmen, farmers and Chicago vacationers built were repaired with glass blocks. These blocks are not easy to work with, a mason with special training is necessary, so fitting them into thick limestone foundations was not an easy trick.

Glass blocks cleverly incorporated into the foundation of a Victorian home. That steam-punk looking pipe is a coal chute.

This window from a building directly behind the 1931 Goetz Theater shows a close-up of the workmanship required to make glass blocks look crisp, clean and even. It’s far more complicated to achieve this than a well-constructed brick wall.

One of our old funeral homes, which is now Mad Charlie’s Cafe off the West side of the Square, made even more complex use of this building material.

A wall constructed of glass block at Mad Charlie’s.

Monroe is the principal town in Green County, which has always been a farming community. We were fortunate to be somewhat shielded from the economic depression of 1930s because of our agricultural focus, which allowed building to continue around town as new business opened, such as the Goetz Jr. theater.

Personally, I believe it’s a blessing that so much of our industrial/commercial architecture from the 1930s has survived— even if a show-shopper like the Goetz Jr. did not. Some of the best glass-blocks-viewing is along the West side of the Square, continuing up through the neighborhood between Twining Park and 15th Avenue, which becomes the road to Madison.

Map of Monroe, WI with the prime glass block territory highlighted in pink. The maroon star shows the location of the Square.

P.S. “Twining Park” is named after US Air Force General and Chief of Staff Nathan Farragut Twining, who was born a few blocks from my home. He is famous as the “UFO” general of Project Blue Book— but this may deserve a post of its own. I’m reasonably sure his family attended the Universalist church with the Youngs.